THE CLIMBING BOY CAMPAIGNS in BRITAIN, C. 1770-1840

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

The Guild News

The Guild News October 2011 In this The Guild travelled to Indianapolis chimney Sweeping Industry on an in August of this year to attend the international level. It is a great hon- issue annual European Federation of our and responsibility and shows Chimney Sweeps (ESCHFOE) con- how far we have come. We can Letter from the ference. This year the conference now work more closely with ESCH- Chairman was hosted in partnership by the FOE and its members to improve AGM and American National Chimney Sweep the national and international chim- Guild and the Chimney Safety ney sweeping industry. Exhibition 2012 Institute of America and we would The second announcement was Barry Chislett like to thank both organisations and that the Guild has been awarded Bruce member all of those that were involved for the honour of hosting the 2013 their hospitality. The conference profile ESCHFOE Technical Meeting. This was a great success and we gained Martin Tradewell – will see delegates from over 20 dif- valuable technical information. It ferent countries travel to the UK to Member Refresher was also valuable to see how a big find out how we operate in our in- Course event is run. dustry and the advances that have Bogus Sweeps The Guild has actively supported been made since 2011. ESCHFOE because we believe that The view from Which just so happens to coincide by working together we can achieve Andalucía with the Guild’s 20th Anniversary. more. More respect for well trained Chimney Horrors professional chimney sweeps and Everyone involved with Guild has better safety standards for the pub- been working hard to improve work- Events Diary lic not just in the UK but worldwide. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The Magdalen Hospital : the Story of a Great Charity

zs c: CCS = CD in- CD THE '//////i////t//t/i//n///////.'/ CO « m INCOKM<i%^2r mmammmm ^X^^^Km . T4 ROBERT DINGLEY, F. R. S. KINDLY LENT BY DINGLEY AFTER THE FROM AN ENGRAVING ( JOHN ESQ.) IN THE BOARD ROOM OF THE HOSPITAL PAINTING BY W. HOARE ( I760) Frontispiece THE MAGDALEN HOSPITAL THE STORY OF A GREAT CHARITY BY THE REV. H. F. B. COMPSTON, M.A., ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OP HEBREW AT KING'S COLLEGE, LONDON PROFESSOR OF DIVINITY AT QUEEN'S COLLEGE, LONDON WITH FOREWORD BY THE MOST REVEREND THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY PRESIDENT OF THE MAGDALEN HOSPITAL WITH TWENTY ILLUSTRATIONS SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE LONDON: 68, HAYMARKET, S.W. 1917 AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM M\ FOREWORD It is a great satisfaction to me to be allowed to introduce with a word of commendation Mr. Compston's admirable history of the Magdalen Hospital. The interest with which I have read his pages will I am sure be shared by all who have at heart the well-being of an Institution which occupies a unique place in English history, although happily there is not anything unique nowadays in the endeavour which the Magdalen Hospital makes in face of a gigantic evil. The story Mr. Compston tells gives abundant evidence of the change for the better in public opinion regarding this crying wrong and its remedy. It shows too the growth of a sounder judg- ment as to the methods of dealing with it. For every reason it is right that this book should have been written, and Mr. -

Measures to Address Air Pollution from Small Combustion Sources

MEASURES TO ADDRESS AIR POLLUTION FROM SMALL COMBUSTION SOURCES February 2, 2018 Editor: Markus Amann International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) 1 Abstract This report reviews the perspectives for reducing emissions from small combustion sources in the residential sector, taking into account recent legislation and expectations on the future of solid fuel use in the residential sector in the EU. It highlights new technologies that enable effective reductions of emissions from these sources if applied at a larger scale, and different types of policy interventions that have proven successful for the reduction of pollution from small combustion sources in the household sector. Case studies address technological aspects as well as strategies, measures and instruments that turned out as critical for the phase‐out of high‐polluting household combustion sources. While constituting about 2.7% of total energy consumption in the EU‐28, solid fuel combustion in households contributes more than 45% to total emissions of fine particulate matter, i.e., three times more than road transport. 2 The authors This report has been produced by Markus Amann1) Janusz Cofala1) Zbigniew Klimont1) Christian Nagl2) Wolfgang Schieder2) Edited by: Markus Amann) Affiliations: 1) International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Laxenburg, Austria 2) Umweltbundesamt Vienna, Austria Acknowledgements This report was produced under Specific Agreement 11 under Framework Contract ENV.C.3/FRA/2013/00131 of DG‐Environment of the European Commission. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the positions of Umweltbundesamt, IIASA or their collaborating and supporting organizations. The orientation and content of this report cannot be taken as indicating the position of the European Commission or its services. -

Periodic Inspections of Residential Heating Appliances for Solid Fuels: Review of Legal Regulations in Selected European Countries

Journal of Ecological Engineering Journal of Ecological Engineering 2021, 22(2), 54–62 Received: 2020.11.16 https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/130879 Accepted: 2020.12.14 ISSN 2299-8993, License CC-BY 4.0 Published: 2021.01.01 Periodic Inspections of Residential Heating Appliances for Solid Fuels: Review of Legal Regulations in Selected European Countries Katarzyna Rychlewska1*, Jolanta Telenga-Kopyczyńska1, Rafał Bigda1, Jacek Żeliński1 1 Institute for Chemical Processing of Coal, ul. Zamkowa 1, 41-803 Zabrze, Poland * Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The article presents the legal framework of periodic control systems of individual heating devices in the Federal Republic of Germany, the Czech Republic and Switzerland. The scope of periodic inspections carried out in con- sidered countries, the persons responsible for performing them, the method of data acquisition and administrative bodies responsible for supervising the fulfillment of the obligation, as well as the sanctions for law violations related to small heat sources operation in the residential sector were discussed. Keywords: emission from residential sector, solid fuel boilers, solid fuel space heaters, legal regulations INTRODUCTION specific cases. Regular inspections of individual heating devices allow the identification of furnac- The housing and communal sector has been es which, due to their age or long-term improper mentioned for many years as the main source of operation, may be in poor technical condition. In air pollutant emissions, such as suspended partic- addition, it is possible to identify the cases where ular matter (PM10 and PM2.5) and polycyclic aro- exceeding the emission standards is due to im- matic hydrocarbons (PAH) [NCEM, 2019; EEA, proper operation of often a new device, which 2019]. -

The Armenian Rebellion of the 1720S and the Threat of Genocidal Reprisal

ARMEN M. AIVAZIAN The Armenian Rebellion of the 1720s and the Threat of Genocidal Reprisal Center for Policy Analysis American University of Armenia Yerevan, Armenia 1997 Copyright © 1997 Center for Policy Analysis American University of Armenia 40 Marshal Bagramian Street Yerevan, 375019, Armenia U.S. Office: 300 Lakeside Drive Oakland, California 94612 This research was carried out in the Center for Policy Analysis at American University of Armenia supported in part by a grant from the Eurasia Foundation. First Edition Printed in Yerevan, Armenia Contents Acknowledgements..................................................................v 1. Introduction.........................................................................1 2. Historical Background.........................................................4 The International Setting Armenian Self-Rule in Karabakh and Kapan and the Armenian Armed Forces The Traditional Military Units of the Karabakh and Kapan Meliks The Material Resources and Local Manufacture of Arms Armenian Military Personnel in Georgia Armenian Military Personnel in the Iranian Service The External Recognition of Armenian Self-Rule in Karabakh and Kapan 3. The Rise of Anti-Armenian Attitudes and Its Ramifications...........................................................21 Preliminary Notes Documents The Irano-Armenian Conflict (1722-1724) Ottoman Decision-Making and Exercise on Extermination During the 1720s The Armenian Casualties Forced Islamization of the Armenian Population The Motives for Anti-Armenian Attitudes -

The Rise of Commercial Empires England and the Netherlands in the Age of Mercantilism, 1650–1770

The Rise of Commercial Empires England and the Netherlands in the Age of Mercantilism, 1650–1770 David Ormrod Universityof Kent at Canterbury The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C David Ormrod 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Plantin 10/12 pt System LATEX2ε [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 81926 1 hardback Contents List of maps and illustrations page ix List of figures x List of tables xi Preface and acknowledgements xiii List of abbreviations xvi 1 National economies and the history of the market 1 Leading cities and their hinterlands 9 Cities, states and mercantilist policy 15 Part I England, Holland and the commercial revolution 2 Dutch trade hegemony and English competition, 1650–1700 31 Anglo-Dutch rivalry, national monopoly and deregulation 33 The 1690s: internal ‘free trade’ and external protection 43 3 English commercial expansion and the Dutch staplemarket, 1700–1770 -

BLACK LONDON Life Before Emancipation

BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation ^^^^k iff'/J9^l BHv^MMiai>'^ii,k'' 5-- d^fli BP* ^B Br mL ^^ " ^B H N^ ^1 J '' j^' • 1 • GRETCHEN HOLBROOK GERZINA BLACK LONDON Other books by the author Carrington: A Life BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation Gretchen Gerzina dartmouth college library Hanover Dartmouth College Library https://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/digital/publishing/ © 1995 Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina All rights reserved First published in the United States in 1995 by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey First published in Great Britain in 1995 by John Murray (Publishers) Ltd. The Library of Congress cataloged the paperback edition as: Gerzina, Gretchen. Black London: life before emancipation / Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-8135-2259-5 (alk. paper) 1. Blacks—England—London—History—18th century. 2. Africans— England—London—History—18th century. 3. London (England)— History—18th century. I. title. DA676.9.B55G47 1995 305.896´0421´09033—dc20 95-33060 CIP To Pat Kaufman and John Stathatos Contents Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi 1. Paupers and Princes: Repainting the Picture of Eighteenth-Century England 1 2. High Life below Stairs 29 3. What about Women? 68 4. Sharp and Mansfield: Slavery in the Courts 90 5. The Black Poor 133 6. The End of English Slavery 165 Notes 205 Bibliography 227 Index Illustrations (between pages 116 and 111) 1. 'Heyday! is this my daughter Anne'. S.H. Grimm, del. Pub lished 14 June 1771 in Drolleries, p. 6. Courtesy of the Print Collection, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 2. -

Chrestomathie Persane, a L'usage Des Éleves De L'école Spéciale Des

Q^. a. w' % CHRESTOMAÏHIE PERSANE A L'USAGE DES ELEVES DE L'ÉCOLE SPÉCIALE DES LANGUES OEIENTALES VIVANTES CH. SCHEFER MEMBRE DK L'INSTITUT, ADMINISTRATKLU DK L'ÉCOLB DKS LANGUES ORIENTALES VIVANTES PA K 1 S EllNEST LEROUX. ÉDITKL'R LIBHAIKE UE LA SOCIÉTÉ ASIATIQUE DE L'ÉCOLE DES LANGUES ORIENTALES VIVANTES, ETC. 28, RUE BONAPARTE, 28 1885. AVANT-PROPOS. Je comptak placer en tête de ce volume un e-ss((i sur Vhistoire des études persanes en Europe depuis le commencement du ^Y/P siècle, mais ce traïunl a pris des proportions assez considé'ahles pour former tin opuscule sépare. Je n'ai pas cru pouvoir lui sacrifier les éclaircissements historiques et géographiques in- sérés dans ce volume, et qui sont indispensables pour éviter au lecteur des recJierches souvent laborieuses. Le second volume de la Chrestomathie persane des- tinée aux élèves de l'Ecole des langues orientales vi- vantes renferme deu,v morceau.v historiques; je dirai les motifs qui me les ont fait choisir. Les événements dont l'Asie a été le théâtre au moyen âge ont eu, dans le monde entier, un retentissement considérable, et on a pu croire, pendant un moment, que l'invasion des Mogols mettrad en. perd rcristence même des peuples de l'Europe centrale. VI AV.\NT-I'KM)I'(»S. (le Ih'jUlis (j//('!(ll/('.s (IH)lf'('-s, l'(lH<'Hti(t)i (/r/tr/'f/lr a, mnircidl, rl(' (tpjjr/rc .s//r Ira jjdij.s (H( rr(///rrrflf les (////Kt.sfk'.s J'oiff/rcs par les (IcucciKhntf-s de, l)j(u/(jif/z Kli(i)t. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

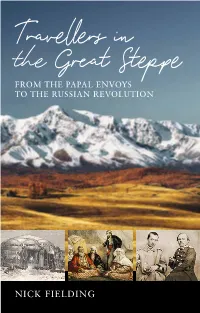

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS .