Hodgman Tidal-Marsh-Birds-SWG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solving Sparrows (Supplemental to the North Branch Nature Center Online Presentation on 1 May 2020) © Bryan Pfeiffer

Solving Sparrows (Supplemental to the North Branch Nature Center Online Presentation on 1 May 2020) © Bryan Pfeiffer 1. Know Song Sparrow and Its Repertoire Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) is one of the most widespread Birds on the continent. It is your “default” sparrow: aBundant, visible, heavily streaked and with a longish tail. You can’t know sparrows until you know Song Sparrow. Its song is variaBle, But most often Begins with two or three repeated short notes followed By a drawn, odd, nasal, somewhat Buzzy note or two, then ending in a trill. Those Oirst few repeated notes are your best handles for learning this song. 2. Learn the “Sparrow Impostors” They included: female Red-winged BlackBird (raucous with a dagger-like Bill), American Pipit (rather than hopping like most other sparrows, it has a silly walk), female Purple Finch and House Finch (high in trees), various streaked thrushes, female BoBolink, female Indigo Bunting, House Sparrow (particularly females), two warbler species: Northern Waterthrush and Louisiana Waterthrush. 3. Is Your Sparrow Clean or Streaked Below? Although this step has some pitfalls, this is a Oine start for Beginning sparrow watchers. It helps you limit your choices. In Vermont, a Birder might encounter aBout a dozen sparrow species in any given year. Swamp Sparrow is sort of an in-betweener. Streaked Clean • Song Sparrow • Chipping Sparrow • Savannah Sparrow • White-throated Sparrow (can be faintly streaked or messy) • Fox Sparrow (migrant) • Swamp Sparrow (dingy) • Lincoln’s Sparrow • American Tree Sparrow (winter) • Vesper Sparrow (upper breast) • White-crowned Sparrow (migrant) • Field Sparrow • Clay-colored Sparrow • Grasshopper Sparrow 4. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Wildlife Habitat Plan

WILDLIFE HABITAT PLAN City of Novi, Michigan A QUALITY OF LIFE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY WILDLIFE HABITAT PLAN City of Novi, Michigan A QUALIlY OF LIFE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY JUNE 1993 Prepared By: Wildlife Management Services Brandon M. Rogers and Associates, P.C. JCK & Associates, Inc. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS City Council Matthew C. Ouinn, Mayor Hugh C. Crawford, Mayor ProTem Nancy C. Cassis Carol A. Mason Tim Pope Robert D. Schmid Joseph G. Toth Planning Commission Kathleen S. McLallen, * Chairman John P. Balagna, Vice Chairman lodia Richards, Secretary Richard J. Clark Glen Bonaventura Laura J. lorenzo* Robert Mitzel* Timothy Gilberg Robert Taub City Manager Edward F. Kriewall Director of Planning and Community Development James R. Wahl Planning Consultant Team Wildlife Management Services - 640 Starkweather Plymouth, MI. 48170 Kevin Clark, Urban Wildlife Specialist Adrienne Kral, Wildlife Biologist Ashley long, Field Research Assistant Brandon M. Rogers and Associates, P.C. - 20490 Harper Ave. Harper Woods, MI. 48225 Unda C. lemke, RlA, ASLA JCK & Associates, Inc. - 45650 Grand River Ave. Novi, MI. 48374 Susan Tepatti, Water Resources Specialist * Participated with the Planning Consultant Team in developing the study. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii PREFACE vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY viii FRAGMENTATION OF NATURAL RESOURCES " ., , 1 Consequences ............................................ .. 1 Effects Of Forest Fragmentation 2 Edges 2 Reduction of habitat 2 SPECIES SAMPLING TECHNIQUES ................................ .. 3 Methodology 3 Survey Targets ............................................ ., 6 Ranking System ., , 7 Core Reserves . .. 7 Wildlife Movement Corridor .............................. .. 9 FIELD SURVEY RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS , 9 Analysis Results ................................ .. 9 Core Reserves . .. 9 Findings and Recommendations , 9 WALLED LAKE CORE RESERVE - DETAILED STUDy.... .. .... .. .... .. 19 Results and Recommendations ............................... .. 21 GUIDELINES TO ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE PLANNING AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION. -

North Texas Winter Sparrows Cheat Sheet *Indicates Diagnostic Feature(S)

North Texas Winter Sparrows Cheat Sheet *Indicates diagnostic feature(s) Genus Spizella 1) American Tree Sparrow - “Average” bird 6.25 inches +/- - Long notched tail - *Thin streak-like rufous patch on the side of the breast - Two white wing bars, upper bar distinctly shorter - *Distinct dark spot on otherwise clear greyish breast - Rufous crown and eye-line on otherwise grey face - *Upper mandible noticeable darker than lower - Prefers brushy edges o Similar species; field sparrow (smaller and paler plumage) 2) Field Sparrow - Smaller bird 5.5 inches +/- “plump” - No streaking on pale grey breast some individuals may have faint reddish flanks - Long narrow tail - A lot of grey on the face, some individuals may have a faint darker grey or reddish eye streak - Two white wing bars, upper bar distinctly shorter - Rufous crown - White eye ring - *Pink bill; in combination with white eye ring and un-streaked breast - Open grasslands and woodland edges o Similar species; American Tree Sparrow (noticeably larger) 3) Chipping Sparrow - Smaller bird 5.5 inches - No streaking on plain grey breast and under parts - Rufous crown sometimes faintly streaked - Two white wing bars, upper bar distinctly shorter - *Dark eye-line coupled with lighter “eyebrow” stripe and rufous crown - Grey rump - Pink bill and legs - Common all over the place in winter o Similar species; Clay-colored Sparrow, a rare migrant Genus Ammodramus 4) Grasshopper Sparrow – a rare winter visitor - Small bird 5 inches - Thick “heavier” bill - Pointed, short tail compared to body -

Illinois Birds: Volume 4 – Sparrows, Weaver Finches and Longspurs © 2013, Edges, Fence Rows, Thickets and Grain Fields

ILLINOIS BIRDS : Volume 4 SPARROWS, WEAVER FINCHES and LONGSPURS male Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder female Photo © John Cassady Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Mary Kay Rubey Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder American tree sparrow chipping sparrow field sparrow vesper sparrow eastern towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus Spizella arborea Spizella passerina Spizella pusilla Pooecetes gramineus Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder lark sparrow savannah sparrow grasshopper sparrow Henslow’s sparrow fox sparrow song sparrow Chondestes grammacus Passerculus sandwichensis Ammodramus savannarum Ammodramus henslowii Passerella iliaca Melospiza melodia Photo © Brian Tang Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Lincoln’s sparrow swamp sparrow white-throated sparrow white-crowned sparrow dark-eyed junco Le Conte’s sparrow Melospiza lincolnii Melospiza georgiana Zonotrichia albicollis Zonotrichia leucophrys Junco hyemalis Ammodramus leconteii Photo © Brian Tang winter Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder summer Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Mark Bowman winter Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder summer Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Nelson’s sparrow -

Song Structure Without Auditory Feedback: Emendations of the Auditory Template Hypothesis

0270~6474/83/0303-0517$02.00/O The Journal of Neuroscience Copyright 0 Society for Neuroscience Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 517-531 Printed in U.S.A. March 1983 SONG STRUCTURE WITHOUT AUDITORY FEEDBACK: EMENDATIONS OF THE AUDITORY TEMPLATE HYPOTHESIS PETER MARLER2 and VIRGINIA SHERMAN Rockefeller University, Field Research Center, Millbrook, New York 12545 Received June 21, 1982; Revised October 1, 1982; Accepted October 8, 1982 Abstract Motor patterns of songs of swamp and song sparrows, Melospiza georgiana and M. melodia, deafened early in life display a significant degree of species-specific structure. Normal songs of the two species differ in the degree to which they are segmented. Swamp sparrow song consists of a single segment, and song sparrow songs are multisegmental. Song and swamp sparrows were deafened at 17 to 23 days, prior to the onset of song or subsong. The song sparrows developed more segments in their singing than the swamp sparrows. Species-specific trends were also evident in song durations and frequency characteristics. Abnormalities were found, however, in the morphology of the notes and syllables from which songs of early deafened sparrows are constructed. These results require emendation of the auditory template hypothesis of song learning in birds. The two most obvious means for exerting genetic con- development and after mature song patterns were crys- trol over the structure of a vocalization are by inherited tallized. In the domestic chicken, renditions of all normal patterns of motor outflow from the brain to the sound- species’ vocal signals were developed by chicks deafened producing organs or by innate auditory “templates” to soon after hatching (Konishi, 1963). -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Sparrows of Lake County Field Guide

V/2•07/2014 Park rangers recommend these six popular The Lake County Department of Public Resources, comprehensive guides: Parks & Trails Division, manages more than three dozen parks, preserves and boat ramps. 1. A FIELD GUIDE TO THE BIRDS, EASTERN AND CENTRAL NORTH AMERICA of Lake County Lake County park rangers lead regularly Sparrows scheduled nature hikes, bird & butterfly surveys (Sixth Edition, 2010, Roger Tory Peterson) 2. STOKES FIELD GUIDE TO BIRDS, Check out Lake County and other outdoor adventures in some of these EASTERN REGION Parks & Trails Division’s collection of parks. In partnership with the Lake County (Second Edition, 2013, educational wildlife pamphlets: Water Authority, Parks & Trails also schedules Donald and Lillian Stokes) guided paddling adventures. For a listing of 3. ALL THE BIRDS OF NORTH AMERICA * Birds of Lake County Lake County parks and events, call (352) 253-4950, (Second Edition, 2002, The American Bird Conservancy) * Butterflies of Lake County e-mail [email protected] or log FIELD GUIDE TO THE BIRDS OF on to www.lakecountyfl.gov/parks. 4. * Eastern Bluebird NORTH AMERICA (Sixth Edition, 2011, * Florida Scrub-jay For more information about sparrows or The National Geographic Society) * Gopher Tortoise other birds, check out a field guide to birds 5. FOCUS GUIDE TO THE BIRDS OF available at many local libraries or bookstores. NORTH AMERICA * Planting Natives vs. Similar Non-Native Information on birds is also available online at (Second Edition, 2005, Kenn Kaufman) * Snakes of Lake County the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 6. THE SIBLEY GUIDE TO BIRDS * Sparrows of Lake County (Second Edition, 2014, David Allen Sibley) www.birds.cornell.edu. -

Structural Changes in Song Ontogeny in the Swamp Sparrow Melospiza Georgiana

STRUCTURAL CHANGES IN SONG ONTOGENY IN THE SWAMP SPARROW MELOSPIZA GEORGIANA PETER MARLER AND SUSAN PETERS RockefellerUniversity Field Research Center, Tyrrel Road,Millbrook, New York 12545USA ABS?RAC?.--Sixteenmale Swamp Sparrowstrained with recordedsongs in infancywere recordedon a weekly basis throughoutthe processof song development.Analyses of the 15,000 songsrecorded from them provided the basis for a seven-stageclassification of the stepsin songontogeny, with the four major divisions of subsong,subplastic song, plastic song,and full song.The individuallyisolated males all followeda basicallysimilar devel- opmental progressionthrough the seven stagesof song development.Accounts of other speciessuggest that the pattern seen in the Swamp Sparrowis a rather generalone, when one allowsfor speciesdifferences in songstructure. The abrupt reductionof songduration and its variability was a marker for the crystallizationof plasticsong into full song.At this time there was also a reduction in the number of syllabletypes used and the number of parts per song.Swamp Sparrows produced considerably more syllabletypes in plasticsong than necessaryto generatethe normal,species-specific song. Received 10 June 1981, accepted 19 October 1981. A GENERALpicture is availableof the overall Four males,designated as the "prehatchtreated" structural properties of subsong and plastic group,were injected with CI628on 4 successivedays songand the transformationsto which they are between8 daysbefore hatching and two daysafter subjectprior to the emergenceof full song hatching. Three males, the "posthatch treated" (Nice 1943, Marlet 1956, Thorpe and Pilcher group, were injectedon 6 successivedays between 3 and 8 days after hatching.A third group of five 1958, Nottebohm 1972a). Despite the plethora males,the "late treated"group, were injectedon 4 of studies on mature birdsong, there has been to 6 successivedays, betweenthe agesof 9 and 24 little descriptive analysis of song ontogeny. -

Estimates of Avian Mortality Attributed to Vehicle Collisions in Canada

Copyright © 2013 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Bishop, C. A., and J. M. Brogan. 2013. Estimates of avian mortality attributed to vehicle collisions in Canada. Avian Conservation and Ecology 8(2): 2. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ACE-00604-080202 Research Paper, part of a Special Feature on Quantifying Human-related Mortality of Birds in Canada Estimates of Avian Mortality Attributed to Vehicle Collisions in Canada Estimation de la mortalité aviaire attribuable aux collisions automobiles au Canada Christine A. Bishop 1 and Jason M. Brogan 2 ABSTRACT. Although mortality of birds from collisions with vehicles is estimated to be in the millions in the USA, Europe, and the UK, to date, no estimates exist for Canada. To address this, we calculated an estimate of annual avian mortality attributed to vehicular collisions during the breeding and fledging season, in Canadian ecozones, by applying North American literature values for avian mortality to Canadian road networks. Because owls are particularly susceptible to collisions with vehicles, we also estimated the number of roadkilled Barn owls (Tyto alba) in its last remaining range within Canada. (This species is on the IUCN red list and is also listed federally as threatened; Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada 2010, International Union for the Conservation of Nature 2012). Through seven Canadian studies in existence, 80 species and 2,834 specimens have been found dead on roads representing species from 14 orders of birds. On Canadian 1 and 2-lane paved roads outside of major urban centers, the unadjusted number of bird mortalities/yr during an estimated 4-mo (122-d) breeding and fledging season for most birds in Canada was 4,650,137 on roads traversing through deciduous, coniferous, cropland, wetlands and nonagricultural landscapes with less than 10% treed area. -

Alternative Crossings: a Study on Reducing Highway 49 Wildlife

Alternative Crossings: A Study On Reducing Highway 49 Wildlife Mortalities Through The Horicon Marsh Prepared By: Bradley Wolf, Pa Houa Lee, Stephanie Marquardt, & Michelle Zignego Table of Contents Chapter 1: Horicon Marsh Background ........................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 History of the Horicon Marsh and Highway 49 ......................................................................................... 2 Geography of the Horicon Marsh ............................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 2: Natural History of Target Species ............................................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Natural History of the Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) ............................................................................... 7 Natural History of the Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) ...................................................................... 9 Natural History of Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) ............................................................................... -

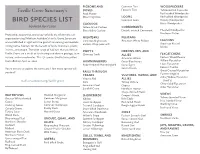

Bird Species List

PIGEONS AND Common Tern WOODPECKERS DOVES Forster’s Tern Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Faville Grove Sanctuary’s Rock Pigeon Red-headed Woodpecker Mourning Dove LOONS Red-bellied Woodpecker BIRD SPECIES LIST Common Loon Downy Woodpecker CUCKOOS Hairy Woodpecker Updated April 2020 Yellow-billed Cuckoo CORMORANTS Black-billed Cuckoo Double-crested Cormorant Pileated Woodpecker Protecting, supporting, and enjoying birds are what make our Northern Flicker organization sing! Madison Audubon’s Faville Grove Sanctuary NIGHTJARS PELICANS American White Pelican FALCONS was established in 1998 with the goal of conserving and reestab- Common Nighthawk Eastern Whip-poor-will American Kestrel lishing native habitats for the benefit of birds, mammals, plants, Merlin insects, and people. The wide range of habitats that you find at SWIFTS HERONS, IBIS, AND Faville Grove are a result of fascinating and diverse geology, burn Chimney Swift ALLIES FLYCATCHERS history, and microclimates. This 171-species bird list was pulled American Bittern Eastern Wood-Pewee from eBird on April 22, 2020. HUMMINGBIRDS Great Blue Heron Willow Flycatcher Ruby-throated Hummingbird Great Egret Least Flycatcher Eastern Phoebe You’re invited to explore the sanctuary. How many species will Green Heron Great Crested Flycatcher you find? RAILS THROUGH CRANES VULTURES, HAWKS, AND Eastern Kingbird Alder/Willow Flycatcher Virginia Rail ALLIES (Traill’s) madisonaudubon.org/faville-grove Sora Turkey Vulture Olive-sided Flycatcher American Coot Osprey Alder Flycatcher Sandhill Crane Northern