Head of Silenus (Fragment of the Visit of Bacchus to Icarius)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: a Metatheatrical Reading of P.Koln VI 242A=Trgf II F646a Anton Bierl

BIERL, ANTON, Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: A Metatheatrical Reading of a New Dramatic Papyrus , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 31:4 (1990:Winter) p.353 Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: A Metatheatrical Reading of P.Koln VI 242A=TrGF II F646a Anton Bierl EW DRAMATIC PAPYRUS1 confronts interpreters with many ~puzzling questions. In this paper I shall try to solve some of these by applying a new perspective to the text. I believe that this fragment is connected with a specific literary feature of drama especially prominent in the bnal decades of the bfth century B.C., viz. theatrical self-consciousness and the use of Dionysus, the god of Athenian drama, as a basic symbol for this tendency. 2 The History of the Papyrus Among the most important papyri brought to light by Anton Fackelmann is an anthology of Greek prose and poetry, which includes 19 verses of a dramatic text in catalectic anapestic tetrameters. Dr Fackelmann entrusted the publication of this papyrus to Barbel Kramer of the University of Cologne. Her editio princeps appeared in 1979 as P. Fackelmann 5. 3 Two years later the verses were edited a second time by Richard Kannicht and Bruno Snell and integrated into the Fragmenta Adespota in 1 This papyrus has already been treated by the author in Dionysos und die griechische Trag odie. Politische und 'metatheatralische' Aspekte im Text (Tiibingen 1991: hereafter 'Bieri') 248-53. The interpretation offered here is an expansion of my earlier provisional comments in the Appendix, presenting fragments of tragedy dealing with Dionysus. 2 See C. -

Instruction Av 04/2020 Issued by the Management Of

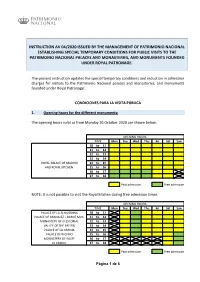

INSTRUCTION AV 04/2020 ISSUED BY THE MANAGEMENT OF PATRIMONIO NACIONAL ESTABLISHING SPECIAL TEMPORARY CONDITIONS FOR PUBLIC VISITS TO THE PATRIMONIO NACIONAL PALACES AND MONASTERIES, AND MONUMENTS FOUNDED UNDER ROYAL PATRONAGE. The present instruction updates the special temporary conditions and reduction in admission charges for visitors to the Patrimonio Nacional palaces and monasteries, and monuments founded under Royal Patronage: CONDICIONES PARA LA VISITA PÚBLICA 1. Opening hours for the different monuments: The opening hours valid as from Monday 26 October 2020 are shown below: OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 13 to 14 ROYAL PALACE OF MADRID 14 to 15 AND ROYAL KITCHEN 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission NOTE: It is not possible to visit the Royal Kitchen during free admission times. OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun PALACE OF LA ALMUDAINA 10 to 11 PALACE OF ARANJUEZ + BARGE MUS. 11 to 12 MONASTERY OF El ESCORIAL 12 to 13 VALLEY OF THE FALLEN 13 to 14 PALACE OF LA GRANJA 14 to 15 PALACE OF RIOFRIO 15 to 16 MONASTERY OF YUSTE 16 to 17 EL PARDO 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission Página 1 de 6 OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10:00 to 10:30 10:30 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 CONVENT OF SANTA MARIA LA REAL HUELGAS 13 to 14 14 to 15 CONVENT OF SANTA CLARA TORDESILLAS 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 18 to 18:30 Paid admission Free admission The Casas del Príncipe (at El Pardo and El Escorial), Casa del Infante (at El Escorial) and Casa del Labrador (at Aranjuez) will not be open. -

BROCHURE-ARRE-2011-UK:Mise En Page 1

Discovering European Heritage in Royal Residences Association of European Royal Residences Contents 3 The Association of European Royal Residences 4 National Estate of Chambord, France 5 Coudenberg - Former Palace of Brussels, Belgium 6 Wilanow Palace Museum, Poland 7 Palaces of Versailles and the Trianon, France 8 Schönbrunn Palace, Austria 9 Patrimonio Nacional, Spain 10 Royal Palace of Gödöllo”, Hungary 11 Royal Residences of Turin and of the Piedmont, Italy 12 Mafra National Palace, Portugal 13 Hampton Court Palace, United Kingdom 14 Peterhof Museum, Russia 15 Royal Palace of Caserta, Italy 16 Prussian Palaces and Gardens of Berlin-Brandenburg, Germany 17 Royal Palace of Stockholm, Sweden 18 Rosenborg Castle, Denmark 19 Het Loo Palace, Netherlands Cover: Chambord Castle. North facade © LSD ● F. Lorent, View from the park of the ruins of the former Court of Brussels, watercolour, 18th century © Brussels, Maison du Roi - Brussels City Museums ● Wilanow Palace Museum ● Palace of Versailles. South flowerbed © château de Versailles-C. Milet ● The central section of the palace showing the perron leading up to the Great Gallery, with the Gloriette in the background © Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H., Vienna ● Real Sitio de La Granja de San Ildefonso © Patrimonio Nacional ● View from the garden © Gödöllo “i Királyi Kastély ● The Margaria © Racconigi ● Venaria Reale. View of the Palace © Venaria Reale ● Mafra National Palace. Photo S. Medeiros © Palacio de Mafra ● Kew Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● White Tower, Tower of London © Historic Royal Palaces ● Kensington Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● Banqueting House © Historic Royal Palaces ● Hampton Court Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● Grand Palace and Grand Cascade © Peterhof Museum ● Caserta – Royal Palace – Great staircase of honour © Soprintendenza BAPSAE. -

Antioch Mosaics and Their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics

JMR 5, 2012 43-57 Antioch Mosaics and their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics José Maria BLÁZQUEZ* – Javier CABRERO** The twenty-two myths represented in Antioch mosaics repeat themselves in those in Hispania. Six of the most fa- mous are selected: Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta and Iphigenia in Aulis. Key words: Antioch myths, Hispania, Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta, Iphigenia in Aulis During the Roman Empire, Hispania maintained good cultural and economic relationships with Syria, a Roman province that enjoyed high prosperity. Some data should be enough. An inscription from Málaga, lost today and therefore from an uncertain date, seems to mention two businessmen, collegia, from Syria, both from Asia, who might form an single college, probably dedicated to sea commerce. Through Cornelius Silvanus, a curator, they dedicated a gravestone to patron Tiberius Iulianus (D’Ors 1953: 395). They possibly exported salted fish to Syria, because Málaca had very big salting factories (Strabo III.4.2), which have been discovered. In Córdoba, possibly during the time of Emperor Elagabalus, there was a Syrian colony that offered a gravestone to several Syrian gods: Allath, Elagabab, Phren, Cypris, Athena, Nazaria, Yaris, Tyche of Antioch, Zeus, Kasios, Aphrodite Sozausa, Adonis, Iupiter Dolichenus. They were possible traders who did business in the capital of Bética (García y Bellido 1967: 96-105). Libanius the rhetorical (Declamatio, 32.28) praises the rubbles from Cádiz, which he often bought, as being good and cheap. -

The Transformation of Arachne Into a Spider.Pdf

Name: Class: The Transformation of Arachne into a Spider By Ovid From Metamorphoses (Book Vi) 8 A.D. Ovid (43 B.C.-17 A.D.) was a Roman poet well-known for his elaborate prose and fantastical imagery. Ovid was similar to his literary contemporary, Virgil, in that both authors played a part in reinventing classical poetry and mythology for Roman culture. Metamorphoses, one of Ovid’s most-read works, consists of a series of short stories and epic poems whose mythological characters undergo transformation in some way or another. As you read, take notes on Ovid’s choice of figurative language and imagery. [1] Pallas,1 attending to the Muse's2 song, Approv'd the just resentment of their wrong; And thus reflects: While tamely3 I commend Those who their injur'd deities4 defend, [5] My own divinity affronted stands, And calls aloud for justice at my hands; Then takes the hint, asham'd to lag behind, And on Arachne' bends her vengeful mind; One at the loom5 so excellently skill'd, [10] That to the Goddess6 she refus'd to yield. Low was her birth, and small her native town, She from her art alone obtain'd renown. Idmon, her father, made it his employ, "Linen Weaving" is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0. To give the spungy fleece7 a purple dye: [15] Of vulgar strain her mother, lately dead, With her own rank had been content to wed; Yet she their daughter, tho' her time was spent In a small hamlet,8 and of mean descent, Thro' the great towns of Lydia gain'd a name, [20] And fill'd the neighb'ring countries with her fame. -

Ancient Egyptians Believed in an Afterlife

Note To the Teacher This kit is designed to help your students learn more about Ancient Egypt by viewing images from the Walters Art Museum collection. The scope ranges from the Middle Kingdom (Dynasties ca. 2061-1640 BCE) through the Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BCE). You will find ten images of objects from Ancient Egypt. In addition to the images, there is a timeline, essays about the museum objects; lesson plans for elementary, middle grades and high school, and bibliographies with resources to assist you in your class presentation. Resources include: a vocabulary list, books for you and your students, websites, videos and other art tools. TRK Borrowing Policy Please… 1. Return this kit in person or by mail on or by its due date. A valid credit card number is required to borrow Teacher Resource Kits. A $25.00 fee will be charged for kits that are returned up to one month late. Borrowers will be assessed the pur- chase cost of kits borrowed if materials are returned more than one month late. The box the TRK was sent in can be reused for its return. 2. Keep your TRK intact and in working order. You are responsible for the contents of this kit while it is in your possession. If any item is miss- ing or damaged, please contact the Department of School Programs at 410.547.9000, ext. 298, as soon as possible. 3. Fill out the TRK Evaluation so that kits can be improved with your input and student feedback. Please return the Teacher Resource Kit to: Department of School Programs Division of Education and Public Programs The Walters Art Museum 600 North Charles Street Baltimore, MD 21201-5185 Copyright Statement Materials contained in this Education kit are not to be reproduced or transmitted in any format, other than for educational use, without specific advance written permission from the Walters Art Museum. -

IBERIAN HOLIDAY MADRID, TOLEDO and SEGOVIA Monday, December 28, 2015 Through Sunday, January 3, 2016

AN IBERIAN HOLIDAY A NEW YEAR’S CELEBRATION IN MADRID, TOLEDO AND SEGOVIA* Monday, December 28, 2015 through Sunday, January 3, 2016 *Itinerary subject to change $ 3,600.00per person INCLUDING AIR $2,400.00 per person LAND ONLY $450.00 additional for SINGLE SUPPLEMENT Join us on our ANNUAL NEW YEAR’S TRIP takes you to SUNNY SPAIN AND THREE OF ITS MOST INTERESTING CITIES – MADRID, TOLEDO AND SEGOVIA. Our custom itinerary showcases a variety of museums, delicious dining experiences and fascinating sites from the ancient to the modern that come together on this wonderful Iberian Holiday. DAY 1 - MONDAY, DECEMBER 28 NEWARK Board United Airlines Flight #964 departing Newark Liberty Airport at 8:20pm for our NON-STOP trip to Madrid DAY 2 - TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29 MADRID (L/D) Arrive at Madrid’s Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport at 9:45am, gather our luggage and meet our coach and guide. After lunch, take a panoramic city tour where you will see many of Madrid’s beautiful Plazas, Monuments, Shopping Streets and Fountains. Visit some of the city’s different districts including the typical "castizo" (Castilian) quarter of "la Moreria." Check into the beautiful and centrally located Four Star Hotel NH Collection Madrid Paseo del Prado at 3:00 Relax for the rest of the afternoon. Dine with your fellow travelers at a festive Welcome Dinner DAY 3 - WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 30 MADRID (B/L/D) Meet our local guide for a short walk to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. Take a guided stroll down the history of European painting, from its beginning in the 13th century to the close of the 20th century by visiting works by Van Eyck, Dürer, Caravaggio, Rubens, Frans Hals, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Kirchner, Mondrian, Klee, Hopper, Rauschenberg .. -

Marsyas in the Garden?

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Habetzeder, J. (2010) Marsyas in the garden?: Small-scale sculptures referring to the Marsyas in the forum Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome, 3: 163-178 https://doi.org/10.30549/opathrom-03-07 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-274654 MARSYAS IN THE GARDEN? • JULIA HABETZEDER • 163 JULIA HABETZEDER Marsyas in the garden? Small-scale sculptures referring to the Marsyas in the forum Abstract antiquities bought in Rome in the eighteenth century by While studying a small-scale sculpture in the collections of the the Swedish king Gustav III. This collection belongs today Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, I noticed that it belongs to a pre- to the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. It is currently being viously unrecognized sculpture type. The type depicts a paunchy, thoroughly published and a number of articles on the col- bearded satyr who stands with one arm raised. To my knowledge, four lection have previously appeared in Opuscula Romana and replicas exist. By means of stylistic comparison, they can be dated to 3 the late second to early third centuries AD. Due to their scale and ren- Opuscula. dering they are likely to have been freestanding decorative elements in A second reason why the sculpture type has not previ- Roman villas or gardens. -

The Night Sky This Month

The Night Sky (June 2019) BST (Universal Time plus one hour) is used this month . The General Weather Pattern June is usually the driest month of the year. Inland, however, cumulous clouds can develop to great heights giving way to thunder storms which signal the end of a dry spell. Here in Wales a coastal fog can sometimes mar an evening. Temperatures are usually above 10 ºC at night, but always prepare for the worst. Should you be interested in obtaining a detailed weather forecast for observing in the Usk area, log on to https://www.meteoblue.com/en/weather/forecast/seeing/usk_united-kingdom_2635052 Other locations are available. Earth (E) The ecliptic is low throughout the night in June and the first half of July. Since the Moon and planets appear to closely follow this path, they will be found low in the night sky too, causing problems for observers combating astronomical twilight and the murk and disturbance of a thicker atmosphere at that elevation. Consequently, planets do not present themselves at their best at this time. However, if that is where they are situated we must make the best of it. In keeping with the equation of time the latest sunset is on the 25th June this year, and the earliest sunrise is on the 18th June. The summer solstice, when daylight lasts longest, is at 15:55 on the 21st June, and darkness is short-lived here in South Wales. Technically, astronomical twilight exists when the centre of the Sun is less than 18º below the horizon. Conditions apply as to the use of this matter. -

Title: Midas, the Golden Age Trope, and Hellenistic Kingship in Ovid's

Title: Midas, the Golden Age trope, and Hellenistic Kingship in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Abstract: This article proposes a sustained politicized reading of the myth of Midas in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It argues that Midas stands, first, as the embodiment of failed, Hellenistic kingship, with its ostentatious display of wealth and heralding of a new Golden Age, and, second, as a warning against the infectious “love of gold”, to which Roman politicians are far from immune. While the capture of Silenus and the golden touch episode link Midas with the tropes of Hellenistic kingship, his involvement in the competition between Pan and Apollo raises questions about the tropes of Roman imperial power itself. 0 Midas, the Golden Age trope, and Hellenistic Kingship in Ovid’s Metamorphoses It might be heaven, this static Plenitude: apples gold on the bough, Goldfinch, goldfish, golden tiger cat stock - Still in one gigantic tapestry – Sylvia Plath, In Midas' Country Ovid provides the fullest and most elaborate account of the myth of Midas that has come down to us from Classical Antiquity. His version conflates what must have been three different myths involving the legendary Phrygian king: first, his encounter with or capture of Silenus, second, the gift of the golden touch, which turned into a curse, and third, his acquisition of ass’s ears –– in Ovid’s version as a punishment by Apollo for his musical preferences. Throughout the narrative (11.85-193) Midas emerges as a figure of ridicule, a man unable to learn from his mistakes1. Despite the amount of criticism that has focused on the Metamorphoses, this episode has attracted remarkably little attention. -

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry

ABSTRACT Sarcophagi in Context: Identifying the Missing Sarcophagus of Helena in the Mausoleum of Constantina Jackson Perry Director: Nathan T. Elkins, Ph.D The Mausoleum of Constantina and Helena in Rome once held two sarcophagi, but the second has never been properly identified. Using the decoration in the mausoleum and recent archaeological studies, this thesis identifies the probable design of the second sarcophagus. This reconstruction is confirmed by a fragment in the Istanbul Museum, which belonged to the lost sarcophagus. This is contrary to the current misattribution of the fragment to the sarcophagus of Constantine. This is only the third positively identified imperial sarcophagus recovered in Constantinople. This identification corrects misconceptions about both the design of the mausoleum and the history of the fragment itself. Using this identification, this thesis will also posit that an altar was originally placed in the mausoleum, a discovery central in correcting misconceptions about the 4th century imperial liturgy. Finally, it will posit that the decorative scheme of the mausoleum was not random, but was carefully thought out in connection to the imperial funerary liturgy itself. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS _____________________________________________ Dr. Nathan T. Elkins, Art Department APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM ____________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE: _____________________ SARCOPHAGI IN CONTEXT: IDENTIFYING THE MISSING SARCOPHAGUS OF HELENA IN THE MAUSOLEUM OF -

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Malibu 2 (Bareiss) (25) CVA 2

CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM UNITED STATES OF AMERICA • FASCICULE 25 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, Fascicule 2 This page intentionally left blank UNION ACADÉMIQUE INTERNATIONALE CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM • MALIBU Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined closed shape, and lids from neck-amphorae ANDREW J. CLARK THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM FASCICULE 2 . [U.S.A. FASCICULE 25] 1990 \\\ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA (Revised for fasc. 2) Corpus vasorum antiquorum. [United States of America.] The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. (Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23) Fasc. 1- by Andrew J. Clark. At head of title: Union académique internationale. Includes index. Contents: fasc. 1. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured amphorae, neck-amphorae, kraters, stamnos, hydriai, and fragments of undetermined closed shapes.—fasc. 2. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined open shape, and lids from neck-amphorae 1. Vases, Greek—Catalogs. 2. Bareiss, Molly—Art collections—Catalogs. 3. Bareiss, Walter—Art collections—Catalogs. 4. Vases—Private collections— California—Malibu—Catalogs. 5. Vases—California— Malibu—Catalogs. 6. J. Paul Getty Museum—Catalogs. I. Clark, Andrew J., 1949- . IL J. Paul Getty Museum. III. Series: Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23, etc. NK4640.C6U5 fasc. 23, etc. 738.3'82'o938o74 s 88-12781 [NK4624.B37] [738.3'82093807479493] ISBN 0-89236-134-4 (fasc.