Palaeochannels of North West India: Review and Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise Skill Gap Study for the State of Haryana.Pdf

District wise skill gap study for the State of Haryana Contents 1 Report Structure 4 2 Acknowledgement 5 3 Study Objectives 6 4 Approach and Methodology 7 5 Growth of Human Capital in Haryana 16 6 Labour Force Distribution in the State 45 7 Estimated labour force composition in 2017 & 2022 48 8 Migration Situation in the State 51 9 Incremental Manpower Requirements 53 10 Human Resource Development 61 11 Skill Training through Government Endowments 69 12 Estimated Training Capacity Gap in Haryana 71 13 Youth Aspirations in Haryana 74 14 Institutional Challenges in Skill Development 78 15 Workforce Related Issues faced by the industry 80 16 Institutional Recommendations for Skill Development in the State 81 17 District Wise Skill Gap Assessment 87 17.1. Skill Gap Assessment of Ambala District 87 17.2. Skill Gap Assessment of Bhiwani District 101 17.3. Skill Gap Assessment of Fatehabad District 115 17.4. Skill Gap Assessment of Faridabad District 129 2 17.5. Skill Gap Assessment of Gurgaon District 143 17.6. Skill Gap Assessment of Hisar District 158 17.7. Skill Gap Assessment of Jhajjar District 172 17.8. Skill Gap Assessment of Jind District 186 17.9. Skill Gap Assessment of Kaithal District 199 17.10. Skill Gap Assessment of Karnal District 213 17.11. Skill Gap Assessment of Kurukshetra District 227 17.12. Skill Gap Assessment of Mahendragarh District 242 17.13. Skill Gap Assessment of Mewat District 255 17.14. Skill Gap Assessment of Palwal District 268 17.15. Skill Gap Assessment of Panchkula District 280 17.16. -

IJSECT September 2015

CHAPTER-X "The movement of goods must imply the transit of ideas and it is the archaeologist's function to elicit the evidence and to draw the proper conclusion from it* (Mallowan, 1965: 1). 312 CONCLUSION We might now look back at the material presented in the preceding chapters and see what general observations can be made from the evidence as regards the (1) distribution of pre-Harappan culture, (2) its origin and (3) its survival. It must once again be emphasized that the most important pre-Harappan culture so far known is Kalibangan, even though we know only a little of the vast information recorded at this site. All other sites have to be viewed and arranged in chronological position in relation to Kalibangan. (A) TERMINOLOGY A sound name or spoliation is necessary for the pre-Harappan culture revealed at Kalibangan and the eleven explored sites on the Sarasvati-Ghaggar-Hakra river. At pre sent} scholars call it by several names such as Kot-Dijian, Kalibangan I and Sothi. Ghosh had in 1965 considered the names "Sarasvati", "Ghaggar", "Kalibangan I" and "Sothi" but he had preferred the last one. Thapar (1965: 136) on comparing the "component elements" from Sothi and Kalibangan I feels that the latter is a more appropriate name for the culture. It is evident from Chapter VII that no two sites have yielded an identical number of ceramic types and wares. This is probably due to our inadequate knowledge of these 313 sites and not to the inherent paucity of ceramic material on them. Hence, it becomes difficult to evaluate all the dis covered sites with Kalibangan I as their yardstick solely on account of the latter having been thoroughly explored and excavated. -

Herein After Termed As Gulf) Occupying an Area of 7300 Km2 Is Biologically One of the Most Productive and Diversified Habitats Along the West Coast of India

6. SUMMARY Gulf of Katchchh (herein after termed as Gulf) occupying an area of 7300 Km2 is biologically one of the most productive and diversified habitats along the west coast of India. The southern shore has numerous Islands and inlets which harbour vast areas of mangroves and coral reefs with living corals. The northern shore with numerous shoals and creeks also sustains large stretches of mangroves. A variety of marine wealth existing in the Gulf includes algae, mangroves, corals, sponges, molluscs, prawns, fishes, reptiles, birds and mammals. Industrial and other developments along the Gulf have accelerated in recent years and many industries make use of the Gulf either directly or indirectly. Hence, it is necessary that the existing and proposed developments are planned in an ecofriendly manner to maintain the high productivity and biodiversity of the Gulf region. In this context, Department of Ocean Development, Government of India is planning a strategy for management of the Gulf adopting the framework of Integrated Coastal and Marine Area Management (ICMAM) which is the most appropriate way to achieve the balance between the environment and development. The work has been awarded to National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa. NIO engaged Vijayalakshmi R. Nair as a Consultant to compile and submit a report on the status of flora and fauna of the Gulf based on secondary data. The objective of this compilation is to (a) evolve baseline for marine flora and fauna of the Gulf based on secondary data (b) establish the prevailing biological characteristics for different segments of the Gulf at macrolevel and (c) assess the present biotic status of the Gulf. -

Government of India Ground Water Year Book of Haryana State (2015

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE (2015-2016) North Western Region Chandigarh) September 2016 1 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE 2015-2016 Principal Contributors GROUND WATER DYNAMICS: M. L. Angurala, Scientist- ‘D’ GROUND WATER QUALITY Balinder. P. Singh, Scientist- ‘D’ North Western Region Chandigarh September 2016 2 FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board has been monitoring ground water levels and ground water quality of the country since 1968 to depict the spatial and temporal variation of ground water regime. The changes in water levels and quality are result of the development pattern of the ground water resources for irrigation and drinking water needs. Analyses of water level fluctuations are aimed at observing seasonal, annual and decadal variations. Therefore, the accurate monitoring of the ground water levels and its quality both in time and space are the main pre-requisites for assessment, scientific development and planning of this vital resource. Central Ground Water Board, North Western Region, Chandigarh has established Ground Water Observation Wells (GWOW) in Haryana State for monitoring the water levels. As on 31.03.2015, there were 964 Ground Water Observation Wells which included 481 dug wells and 488 piezometers for monitoring phreatic and deeper aquifers. In order to strengthen the ground water monitoring mechanism for better insight into ground water development scenario, additional ground water observation wells were established and integrated with ground water monitoring database. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A&B VILLAGE, & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIST.RICT BHIWANI Director of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, 1995 , . '. HARYANA C.D. BLOCKS DISTRICT BHIWANI A BAWAN I KHERA R Km 5 0 5 10 15 20 Km \ 5 A hAd k--------d \1 ~~ BH IWANI t-------------d Po B ." '0 ~3 C T :3 C DADRI-I R 0 DADRI - Il \ E BADHRA ... LOHARU ('l TOSHAM H 51WANI A_ RF"~"o ''''' • .)' Igorf) •• ,. RS Western Yamuna Cana L . WY. c. ·......,··L -<I C.D. BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUtORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1 ,1. 1990 BOUNDARY , STAT E ... -,"p_-,,_.. _" Km 10 0 10 11m DI';,T RI CT .. L_..j__.J TAHSIL ... C. D . BLOCK ... .. ~ . _r" ~ V-..J" HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT : TAHSIL: C D.BLOCK .. @:© : 0 \ t, TAH SIL ~ NHIO .Y'-"\ {~ .'?!';W A N I KHERA\ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. (' ."C'........ 1 ...-'~ ....... SH20 STATE HIGHWAY ., t TAHSil '1 TAH SIL l ,~( l "1 S,WANI ~ T05HAM ·" TAH S~L j".... IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD .. '\ <' .i j BH IWAN I I '-. • r-...... ~ " (' .J' ( RAILWAY LINE WIT H STA110N, BROAD GAUGE . , \ (/ .-At"'..!' \.., METRE GAUGE · . · l )TAHSIL ".l.._../ ' . '1 1,,1"11,: '(LOHARU/ TAH SIL OAORI r "\;') CANAL .. · .. ....... .. '" . .. Pur '\ I...... .( VILLAGE HAVING 5000AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME ..,." y., • " '- . ~ :"''_'';.q URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- CLASS l.ltI.IV&V ._.; ~ , POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE ... .. .....PTO " [iii [I] DEGREE COLLE GE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION.. '" BOUNDARY . STATE REST HOuSE .TRAVELLERS BUNGALOW AND CANAL: BUNGALOW RH.TB .CB DISTRICT Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/CB elc. -

(Stores & Workshop), UHBVN, Dhulkote

Telephone Numbers of Superintending Engineer (Stores & Workshop), UHBVN, Dhulkote Office Sr. No. Name of Officer/Official Mobile Number Email Address Telephone No. 0171-2542985 [email protected] 1 Er. Palvinder Kumar, SE/S&W Dhulkote 90509-41800 (FAX) 2543432 2 Sh.Satish Sharma, Sr.A.O 93153-34822 0171-2540528 [email protected] 3 Er. Yoginder Malik, SDO/AE/Stores 93559-64400 0171-2542985 [email protected] 4 Er. Suresh Kumar, AEE/Works 87081-48252 0171-2542985 [email protected] 5 Er. D. S. Narwal, XEN/CS & GW 93550-64558 0171-2541099 [email protected] 6 Er. Yoginder Malik, SDO TRW 93559-64400 0171-2540122 [email protected] Er.Ajay Aggarwal, SDO TRW, Mathana, Dual with THW 7 79882-32288 01744-239513 [email protected] Jyotisar 8 Er.Sarvesh Kumar, AE TRW Karnal 74194-88554 0184-2265465 [email protected] 9 Er. Jitender Kumar, AE THW Sonipat 74194-88555 0130-2230981 [email protected] 10 Er. Sandeep Kumar Kundu, AEE works Rohtak 93557-54648 01262-276549 [email protected] 11 Er. Khub Chand SDO (Dual Charge) TRW Panipat 93153-99174 , 94666-76528 (W) 01263-258631 [email protected] 12 Er. Neeraj Grover, SDO works Kaithal 74194-88551, 92533-48562 (W) 01746-269952 [email protected] 13 Er. B.S Narwal, XEN GWS 93550-64558 0171-2541099 [email protected] 14 Er. Yoginder Malik, SDO GWS 93559-64400 0171-2540122 [email protected] 15 Er.B.S Narwal, XEN CS 93550-64558 0171-2540275 [email protected] 16 Er. -

Sarasvati Civilization, Script and Veda Culture Continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution

Sarasvati Civilization, script and Veda culture continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution The monograph is presented in the following sections: Introduction including Abstract Section 1. Tantra yukti deciphers Indus Script Section 2. Momentous discovery of Soma samsthā yāga on Vedic River Sarasvati Basin Section 3. Binjor seal Section 4. Bhāratīya itihāsa, Indus Script hypertexts signify metalwork wealth-creation by Nāga-s in paṭṭaḍa ‘smithy’ = phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office, keeper of all accounts, registers’ Section 5. Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan is an Indus Script hypertext to signify Superintendent of phaḍa ‘metala manufactory’ Section 6. Note on the cobra hoods of Daimabad chariot Section 7 Note on Mohenjo-daro seal m0304: phaḍā ‘metals manufactory’ Section 8. Conclusion Introduction The locus of Veda culture and Sarasvati Civilization is framed by the Himalayan ranges and the Indian Ocean. 1 The Himalayan range stretches from Hanoi, Vietnam to Teheran, Iran and defines the Ancient Maritime Tin Route of the Indian Ocean – āsetu himācalam, ‘from the Setu to Himalayaś. Over several millennia, the Great Water Tower of frozen glacial waters nurtures over 3 billion people. The rnge is still growing, is dynamic because of plate tectonics of Indian plate juttng into and pushing up the Eurasian plate. This dynamic explains river migrations and consequent desiccation of the Vedic River Sarasvati in northwestern Bhāratam. Intermediation of the maritime tin trade through the Indian Ocean and waterways of Rivers Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, Ganga, Sarasvati, Sindhu, Persian Gulf, Tigris-Euphrates, the Mediterranean is done by ancient Meluhha (mleccha) artisans and traders, the Bhāratam Janam celebrated by R̥ ṣi Viśvāmitra in R̥ gveda (RV 3.53.12). -

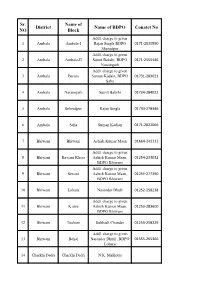

Sr. NO District Name of Block Name of BDPO Conatct No

Sr. Name of District Name of BDPO Conatct No NO Block Addl. charge to given 1 Ambala Ambala-I Rajan Singla BDPO 0171-2530550 Shazadpur Addl. charge to given 2 Ambala Ambala-II Sumit Bakshi, BDPO 0171-2555446 Naraingarh Addl. charge to given 3 Ambala Barara Suman Kadain, BDPO 01731-283021 Saha 4 Ambala Naraingarh Sumit Bakshi 01734-284022 5 Ambala Sehzadpur Rajan Singla 01734-278346 6 Ambala Saha Suman Kadian 0171-2822066 7 Bhiwani Bhiwani Ashish Kumar Maan 01664-242212 Addl. charge to given 8 Bhiwani Bawani Khera Ashish Kumar Maan, 01254-233032 BDPO Bhiwani Addl. charge to given 9 Bhiwani Siwani Ashish Kumar Maan, 01255-277390 BDPO Bhiwani 10 Bhiwani Loharu Narender Dhull 01252-258238 Addl. charge to given 11 Bhiwani K airu Ashish Kumar Maan, 01253-283600 BDPO Bhiwani 12 Bhiwani Tosham Subhash Chander 01253-258229 Addl. charge to given 13 Bhiwani Behal Narender Dhull , BDPO 01555-265366 Loharu 14 Charkhi Dadri Charkhi Dadri N.K. Malhotra Addl. charge to given 15 Charkhi Dadri Bond Narender Singh, BDPO 01252-220071 Charkhi Dadri Addl. charge to given 16 Charkhi Dadri Jhoju Ashok Kumar Chikara, 01250-220053 BDPO Badhra 17 Charkhi Dadri Badhra Jitender Kumar 01252-253295 18 Faridabad Faridabad Pardeep -I (ESM) 0129-4077237 19 Faridabad Ballabgarh Pooja Sharma 0129-2242244 Addl. charge to given 20 Faridabad Tigaon Pardeep-I, BDPO 9991188187/land line not av Faridabad Addl. charge to given 21 Faridabad Prithla Pooja Sharma, BDPO 01275-262386 Ballabgarh 22 Fatehabad Fatehabad Sombir 01667-220018 Addl. charge to given 23 Fatehabad Ratia Ravinder Kumar, BDPO 01697-250052 Bhuna 24 Fatehabad Tohana Narender Singh 01692-230064 Addl. -

Vision Document for Haryana

1 VISION DOCUMENT FOR HARYANA The main aim of this document and policy directive is to provide general guidelines to make the State financially healthy, lead to Economic Growth, reduce borrowings by the State, and encourage industry and generate employment and job opportunities. Main Areas of Focus for development would - Industry, agriculture, service sector and development of tourism with special emphasis on religious tourism and cultural heritage. Literacy rate of Haryana shall be raised to 85%. Target would be to increase GDP growth rate to 10% plus within 5 years. The ultimate aim is to raise the Happiness index of the Citizens. Overall aim would be for “DEVELOPING ZERO DEFECT INDUSTRY WITH ZERO EFFECT ON ENVIRONMENT” in five years. Our motto “Minimum Government and Maximum Governance”. OTHER STRUCTURAL HIGHLIGHTS: We would ensure strict implementation of ban on Cow slaughter in Haryana. Separate high court would be set up for Haryana. Sutlej Yamuna Link Canal would be completed. URBAN FOCUS AND NCR - The overall development of all the districts through empowered local bodies and Panchayats. NCR Development Authority will be set for special emphasis on the development of NCR and its economic advantages. SEPARATE CAPITAL OF HARYANA SHALL BE SET UP AS A SMART CITY WITH HIGH TECHNOLOGY. 2 GURGAON NCR DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY: Gurgaon NCR Development Authority would be created for areas comprising of the district of Gurgaon, Faridabad and Rewari for enabling the integrated development of these areas. SONEPAT NCR DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY: Sonepat NCR Development Authority would be created for areas comprising of the districts of Sonepat, Rohtak and Jhajhar to enable integrated development of these areas. -

27. Wetland Birds Zool

P. Kumar andOur S.K. Nature Gupta (2009)/ Our Nature 7:212-217 (2009) 7: 187-192 Diversity and Abundance of Wetland Birds around Kurukshetra, India P. Kumar* and S.K. Gupta Department of Zoology, University College, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra- 136119, Haryana, India *E-mail: [email protected] Received: 27.04.2009, Accepted: 15.10.2009 Abstract Kurukshrtra is a place of great historical and religious importance in India and is dotted with a number of holy water bodies and ponds. These wetlands support a rich avian diversity and serve as winter sojourn. A total of 54 species of wetland birds belonging to 36 genera and 15 families distributed in 5 orders have been recorded around Kurukshrtra .These wetlands are under pressure from diverse anthropogenic activities. This paper provides an overview of status of wetland birds and threats to them in the study area. Key words : Wetland birds, diversity, abundance, Kurukshetra Introduction Wetlands are defined as lands transitional Verma et al ., 2004; Reginald et al ., 2007). between terrestrial and aquatic eco-systems Water birds have long attracted the attention where the water table is usually at or near of the public and scientists because of their the surface or the land is covered by shallow beauty, abundance, visibility and social water (Mitsch and Gosselink, 1986). behavior, as well as for their recreational Wetlands are among the most productive and economic importance. Recently, water ecosystems in the world and play vital role birds have become of interest as indicators in flood control, aquifer recharge, nutrient of wetland quality and as parameters of absorption and erosion control. -

Haryana Chapter Kurukshetra

Panchkula Yamunanagar INTACH Ambala Haryana Chapter Kurukshetra Kaithal Karnal Sirsa Fatehabad Jind Panipat Hisar Sonipat Rohtak Bhiwani Jhajjar Gurgaon Mahendragarh Rewari Palwal Mewat Faridabad 4 Message from Chairman, INTACH 08 Ambala Maj. Gen. L.K. Gupta AVSM (Retd.) 10 Faridabad-Palwal 5 Message from Chairperson, INTACH Haryana Chapter 11 Gurgaon Mrs. Komal Anand 13 Kurukshetra 7 Message from State Convener, INTACH Haryana Chapter 15 Mahendragarh Dr. Shikha Jain 17 Rohtak 18 Rewari 19 Sonipat 21 Yamunanagar 22 Military Heritage of Haryana by Dr. Jagdish Parshad and Col. Atul Dev SPECIAL SECTION ON ARCHAEOLOGY AND RAKHIGARHI 26 Urban Harappans in Haryana: With special reference to Bhiwani, Hisar, Jhajjar, Jind, Karnal and Sirsa by Apurva Sinha 28 Rakhigarhi: Architectural Memory by Tapasya Samal and Piyush Das 33 Call for an International Museum & Research Center for Harrapan Civilization, at Rakhigarhi by Surbhi Gupta Tanga (Director, RASIKA: Art & Design) MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN INTACH Over 31 years from its inception, INTACH has been dedicated towards conservation of heritage, which has reflected in its various works in the field of documentation of tangible and intangible assets. It has also played a crucial role in generating awareness about the cultural heritage of the country, along with heritage awareness programmes for children, professionals and INTACH members. The success of INTACH is dedicated to its volunteers, conveners and members who have provided valuable inputs and worked in coordination with each other. INTACH has been successful in generating awareness among the local people by working closely with the local authorities, local community and also involving the youth. There has been active participation by people, with addition of new members every year. -

Distinctive Cultural and Geographical Legacy of Bahawalpur by Samia Khalid and Aftab Hussain Gilani

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 2, No. 2 (2010) Distinctive Cultural and Geographical Legacy of Bahawalpur By Samia Khalid and Aftab Hussain Gilani Geographical introduction: The Bahawalpur State was situated in the province of Punjab in united India. It was established by Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan I in 1739, who was granted a title of Nawab by Nadir Shah. Technically the State, had come into existence in 1702 (Aziz, 244, 2006).1 According to the first English book on the State of Bahawalpur, published in mid 19th century: … this state was bounded on east by the British possession of Sirsa, and on the west by the river Indus; the river Garra forms its northern boundary, Bikaner and Jeyselmeer are on its southern frontier…its length from east to west was 216 koss or 324 English miles. Its breadth varies much: in some parts it is eighty, and in other from sixty to fifteen miles. (Ali, Shahamet, b, 1848) In the beginning of the 20th century, this State lay in the extreme south- west of the Punjab province, between 27.42’ and 30.25’ North and 69.31’ and 74.1’ East with an area of 15,918 square miles. Its length from north-east to south-west was about 300 miles and its mean breadth is 40 miles. Of the total area, 9,881 square miles consists of desert regions with sand-dunes rising to a maximum height of 500 feet. The State consists of 10 towns and 1,008 villages, divided into three Nizamats (administrative Units): Minchinabad, Bahawalpur and Khanpur.