[Sample B: Approval/Signature Sheet]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

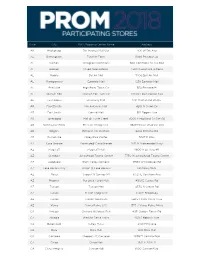

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC . 1101 BANNISTER PL CHARLOTTE NC 28213 510.98 1 STOP MAIL SHOP 8206 PROVIDENCE RD CHARLOTTE NC 28277 86.92 1021 ALLEN LLC . 1021 ALLEN ST CHARLOTTE NC 28205 419.39 1060 CREATIVE INC 801 CLANTON RD CHARLOTTE NC 28217 347.12 112 AUTO ELECTRIC 210 DELBURG ST DAVIDSON NC 28036 45.32 1209 FONTANA AVE LLC . FONTANA AV CHARLOTTE 22.01 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1207 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 2896.87 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1201 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 6942.12 1233 MOREHEAD LLC . 630 402 CALVERT ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 1753.48 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BLVD LLC . 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 1352.65 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . HUNTING BIRDS LN MECKLENBURG 444.12 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . STEELE CREEK RD MECKLENBURG 2229.49 1787 JAMESTON DR LLC . 1787 JAMESTON DR CHARLOTTE NC 28209 3494.88 1801 COMMONWEALTH LLC . 1801 COMMONWEALTH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 9819.32 1961 RUNNYMEDE LLC . 5419 BEAM LAKE DR UNINCORPORATED 958.87 1ST METROPOLITAN MORTGAGE SUITE 333 3420 TORINGDON WY CHARLOTTE NC 28277 15.31 2 THE MAX SALON 10223 E UNIVERSITY CITY BV CHARLOTTE NC 28262 269.96 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 201 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 396.11 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 237 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 49.80 2010 TRYON REAL ESTATE LLC . 2010 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28203 3491.48 208 WONDERWOOD TREE PRESERVATION HO . -

Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers Dana Armstrong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Dana, "Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1711. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1711 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies from William & Mary by Dana Ellise Armstrong Accepted for ______Honors_________ (Honors) _________________________________________ Elizabeth Losh, Director Brian Castleberry _________________________________________ Brian Castleberry Jon Pineda _________________________________________ Jon Pineda Candice Benjes-Small _____________________________ Candice Benjes-Small ______________________________________ Stephanie Hanes-Wilson Williamsburg, VA May 14, 2021 Acknowledgements There is nothing quite like finding the continued motivation to work on a thesis during a pandemic. I would like to extend a huge thank you to all of the people who provided me moral support and guidance along the way. To my thesis and major advisor, Professor Losh, thank you for your edits and cheerleading to get me through the writing process and my self-designed journalism major. -

Stimulating Supermarket Development in Maryland

STIMULATING SUPERMARKET DEVELOPMENT IN MARYLAND A report of the Maryland Fresh Food Retail Task Force Task Force Baltimore Development Maryland Department of Maryland Family Network Safeway Inc. Members Corporation Agriculture Linda Ramsey, Deputy Director Greg Ten Eyck, Director of Public Will Beckford, Executive Director Joanna Kille, Director of of Family Support Affairs and Government Relations of Commercial Revitalization Government Relations Margaret Williams, Executive (Task force co-chair) Advocates for Children Kristen Mitchell, Senior Economic Mark Powell, Chief of Marketing Director and Youth Development Officer and Agribusiness Development Santoni’s Super Market Becky Wagner, Executive Director Leon Pinkett, Senior Economic Maryland Food Bank Rob Santoni, Owner (Task force co-chair and Development Officer Maryland Department of Deborah Flateman, CEO convening partner) Business and Economic Saubel’s Markets Bank of America Development Maryland Governor’s Office Greg Saubel, President Ahold USA Brooke Hodges, Senior Vice Victor Clark, Program Manager, for Children Tom Cormier, Director, President Office of Small Business Christina Drushel, Interagency Supervalu Government Affairs Dominick Murray, Deputy Prevention Specialist Tim Parks, Area Sales Director, B. Green Co. Secretary Eastern Region Angels Food Market Benjy Green, CEO Maryland Hunger Solutions Walt Clocker, Owner and Chairman Maryland Department of Cathy Demeroto, Director The Association of Baltimore of the Maryland Retailers CommonHealth ACTION Health and Mental -

Developing Community Gardens and Improving Food Security a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College

Growing What You Eat: Developing Community Gardens and Improving Food Security A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Michelle P. Corrigan June 2010 © 2010 Michelle P. Corrigan. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Growing What You Eat: Developing Community Gardens and Improving Food Security by MICHELLE P. CORRIGAN has been approved for the Department of Geography and the College of Arts and Sciences by Geoffrey L. Buckley Associate Professor of Geography Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT CORRIGAN, MICHELLE P., M.A., June 2010, Geography Growing What You Eat: Developing Community Gardens and Improving Food Security (131 pp.) Director of Thesis: Geoffrey L. Buckley Food insecurity and awareness are growing concerns in the United States. In addition to studying issues of supply and distribution, scholars and activists working in the field have turned their attention to food-related health problems such as obesity and diabetes. This has caused many to explore the extent to which Americans are engaged and involved in food systems. One way people are engaging with food systems is through community food security approaches such as community gardening. The popularity of community gardening and the localization of food production are evident across the country in cities, small towns, and rural areas eager to narrow the gap between production and consumption. In-depth interviews and field observations from Baltimore, Maryland and Athens, Ohio were used to examine the challenges of community gardening and determine the involvement people have within the food system from their experience with community gardening. -

Affiliate Graduate Faculty at VCU

Graduate scnoo\ Affiliate Graduate Faculty at VCU Abdulmalik, Osheiza Y. Senior Research Associate The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Philadelphia, PA Abdulmajeed, Awab Assistant Professor Department of General Practice School of Dentistry Virginia Commonwealth University Accardo, Jennifer Assistant Professor Department of Pediatrics and Neurology Virginia Commonwealth University Adams, Robert Assistant Professor Department of Radiation Oncology University of North Carolina School of Medicine Chapel Hill, NC Adams, Todd Assistant Professor Department of Radiation Oncology School of Medicine Virginia Commonwealth University Adams, Virginia Senior Cancer Genetic Counselor Informed Medical Decisions Adkins, Amy Assistant Professor Department of Psychology Virginia Commonwealth University Adler, Carrie Global Clinical Application Scientist Clinical Research and Diagnostics Segment Marketing Agilent Technologies, Inc. Alder, Kelly Adjunct Instructor Department of Communication Arts School of the Arts Virginia Commonwealth University Adler, Stuart Professor Department of Microbiology & Immunology Virginia Commonwealth University Alcaine, Jose Affiliate Assistant Professor Department of Foundations of Education School of Education Virginia Commonwealth University Allen, Micah Naturopathic Physician and Licensed Acupuncturist Essential Natural Health, LLC Richmond, VA Allen, Siemon Instructor Department of Sculpture and Extended Media Virginia Commonwealth University Alsharifi, Thamir Researcher Practice Lab College of Engineering Virginia -

Table 10 Papers Not Responding to the ASNE Survey Ranked by Circulation

Table 10 Papers not responding to the ASNE survey Ranked by circulation (DNR = did not report to ASNE last year, too.) Source: Report to the Knight Foundation, May 2004 by Bill Dedman and Stephen K. Doig. The full report is at http://www.asu.edu/cronkite/asne Rank Newspaper, State Weekday Ownership Circulation Staff non-white % circulation area non- for previous year white % (year-end 2002), if paper responded 1 New York Post, New York 652,426 40.3 DNR 2 Chicago Sun-Times, Illinois 481,798 Hollinger International 50.3 DNR (Ill.) 3 The Star-Ledger, Newark, New Jersey 408,672 Advance (Newhouse) 36.8 16.5 (N.Y.) 4 The Columbus Dispatch, Ohio 252,564 17.3 DNR 5 Boston Herald, Massachusetts 241,457 Herald Media (Mass.) 21.1 5.5 6 The Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, 207,538 24.7 21.1 Oklahoma 7 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, 183,343 Wehco Media (Ark.) 22.1 DNR Arkansas 8 The Providence Journal, Rhode Island 167,609 Belo (Texas) 17.3 DNR Page 1 Rank Newspaper, State Weekday Ownership Circulation Staff non-white % circulation area non- for previous year white % (year-end 2002), if paper responded 9 Las Vegas Review-Journal, Nevada 160,391 Stephens Media Group 39.8 DNR (Donrey) (Nev.) 10 Daily Herald, Arlington Heights, 150,364 22.6 5.7 Illinois 11 The Washington Times, District of 102,255 64.3 DNR Columbia 12 The Post and Courier, Charleston, South 98,896 Evening Post Publishing 35.9 DNR Carolina (S.C.) 13 San Francisco Examiner, California 95,800 56.4 18.9 14 Mobile Register, Alabama 95,771 Advance (Newhouse) 33.0 8.6 (N.Y.) 15 The Advocate, -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Ed 300 576 Title Institution Spons Agency Pub Date Note

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 576 CE 051 175 TITLE Virginia Future Business Leaders of America State Handbook. INSTITUTION Henrico County Public Schools, Glen Allen, VA. Virginia Vocational Curriculum Center. SPONS AGENCY Virginia State Dept. of Education, Richmond. Div. of Vocational and Adult Education. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 187p. AVAILABLE FROMVirginia Vocational Curriculum and Resource Center, 2200 Mountain Road, Glen Allen, VA 23060 ($12.38). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Business Education; Job Skills; *Leadership Training; Learning Activities; Office Occupations Education; Postsecondary Education; Program Descriptions; *Program Development; *Program Implementation; Secondary Education; *Student Organizations; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *Future Business Leaders of America; *Virginia ABSTRACT This handbook provides information on starting and conducting a Future Business Leaders of America program in Virginia schools. The guide is organized in seven sections that cover the following topics: introduction to Future Business Leaders of America (organization, organization chart, map, pledge, creed, goals); bylaws; dues and membership/special recognition; officer candidates; chapter promotion; program of work (meeting planning, workform, chapter activity report form, annual evaluation report form); and competitive events (awards, point system, descriptions of events). Appendixes list state and national officers and outline chapter ceremonies. (KC) Reproductions -

Pharmacies Participating in 90-Day Extended Network

Ambetter from Peach State Health Plan: Pharmacies Participating in 90-Day Extended Network City Name Address 1 Zip Code Phone 24-Hour Chain Name ABBEVILLE ABBEVILLE DISCOUNT DRUGS 201 W MAIN ST 310011213 229 467-2221 N LEADER DRUG STORES INC ACWORTH CVS PHARMACY 4595 HWY 92 30102 770 529-9712 N CVS PHARMACY INC ACWORTH CVS PHARMACY 3513 BAKER RD STE 500 30101 770 917-0408 N CVS PHARMACY INC ACWORTH DOLLAR PRESCRIPTION SHOP TOO 2151 CEDARCREST RD 30101 770 672-0846 N THIRD PARTY STATION CP ACWORTH ELDERCARE PHARMACY 4769 S MAIN ST 30101 770 974-4277 N MHA LONG TERM CARE NETWORK ACWORTH KROGER PHARMACY 6199 HIGHWAY 92 30102 770 924-9105 N THE KROGER CO ACWORTH KROGER PHARMACY 1720 MARS HILL RD 30101 770 419-5495 N THE KROGER CO ACWORTH KROGER PHARMACY 3330 COBB PARKWAY 30101 770 975-8776 N THE KROGER CO ACWORTH LACEY DRUG COMPANY 4797 S MAIN ST 301015392 770 974-3131 N ELEVATE PROVIDER NETWORK ACWORTH LACEYS LTC PHCY 4469 LEMON ST 30101 678 236-0400 N GERIMED LTC NETWORK INC ACWORTH PUBLIX PHARMACY #0566 1727 MARS HILL RD 30101 770 218-2426 N PUBLIX SUPER MARKETS INC ACWORTH PUBLIX PHARMACY #0593 3507 BAKER ROAD SUITE 300 30101 770 917-0218 N PUBLIX SUPER MARKETS INC ACWORTH PUBLIX PHARMACY #1096 6110 CEDARCREST ROAD NW 30101 678 439-3446 N PUBLIX SUPER MARKETS INC ACWORTH RED CARPET PHARMACY 3450 COBB PKWY NW STE 110 301018351 770 529-9277 N LEADER DRUG STORES INC ACWORTH RITE AID PHARMACY 11732 3245 COBB PARKWAY 30101 770 974-0936 N RITE AID CORPORATION ACWORTH RITE AID PHARMACY 11733 1775 MARS HILL ROAD 30101 770 919-0882 N RITE AID -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

State City Shopping Center Address

State City Shopping Center Address AK ANCHORAGE 5TH AVENUE MALL SUR 406 W 5TH AVE AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL 3400 BELL AIR MALL AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE AR JONESBORO MALL @ TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPG CNTR 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD AZ FLAGSTAFF FLAGSTAFF MALL 4600 N US HWY 89 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CTR 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS @ LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N AZ MESA SUPERST'N SPRINGS ML 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE AZ NOGALES MARIPOSA WEST PLAZA 220 W MARIPOSA RD AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD AZ PHOENIX CHRISTOWN SPECTRUM 1727 W BETHANY HOME RD AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHPG CNTR 3501 E BROADWAY AZ TUCSON TUCSON MALL 4530 N ORACLE RD AZ TUCSON TUCSON SPECTRUM 5265 S CALLE SANTA CRUZ AZ YUMA YUMA PALMS S C 1375 S YUMA PALMS PKWY CA ANTIOCH ORCHARD @SLATTEN RCH 4951 SLATTEN RANCH RD CA ARCADIA WESTFLD SANTA ANITA 400 S BALDWIN AVE CA BAKERSFIELD VALLEY PLAZA 2501 MING AVE CA BREA BREA MALL 400 BREA MALL CA CARLSBAD PLAZA CAMINO REAL 2555 EL CAMINO REAL CA CARSON SOUTHBAY PAV @CARSON 20700 AVALON