Competition Issues Related to Sports 1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UEFA Expert Group Statement on Nutrition in Elite Football. Current

Consensus statement Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101961 on 23 October 2020. Downloaded from UEFA expert group statement on nutrition in elite football. Current evidence to inform practical recommendations and guide future research James Collins,1,2 Ronald John Maughan,3 Michael Gleeson,4 Johann Bilsborough,5,6 Asker Jeukendrup,4,7 James P Morton,8 S M Phillips ,9 Lawrence Armstrong,10 Louise M Burke ,11 Graeme L Close ,8 Rob Duffield ,5,12 Enette Larson- Meyer,13 Julien Louis ,8 Daniel Medina,14 Flavia Meyer ,15 Ian Rollo,4,16 Jorunn Sundgot- Borgen ,17 Benjamin T Wall,18 Beatriz Boullosa,19 Gregory Dupont ,8 Antonia Lizarraga,20 Peter Res,21 Mario Bizzini,22 Carlo Castagna ,23,24,25 Charlotte M Cowie,26,27 Michel D’Hooghe,27,28 Hans Geyer,29 Tim Meyer ,27,30 Niki Papadimitriou,31 Marc Vouillamoz,31 Alan McCall 2,12,32 For numbered affiliations see ABSTRACT an attempt to prepare players to cope with these end of article. Football is a global game which is constantly evolving, evolutions and to address individual player needs. showing substantial increases in physical and technical Nutrition can play a valuable role in optimising the Correspondence to demands. Nutrition plays a valuable integrated role in physical and mental performance of elite players Dr Alan McCall, Arsenal Performance and Research optimising performance of elite players during training during training and match- play, and in maintaining team, Arsenal Football Club, and match- play, and maintaining their overall health their overall health throughout a long season. -

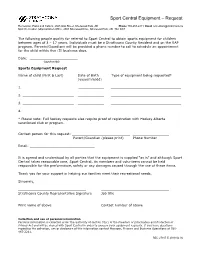

Sport Central Equipment – Request

Sport Central Equipment – Request Recreation, Parks and Culture, 2025 Oak Street, Sherwood Park, AB Phone 780-467-2211 Email [email protected] Mail: Recreation Administration Office, 2001 Sherwood Drive, Sherwood Park, AB T8A 3W7 The following people qualify for referral to Sport Central to obtain sports equipment for children between ages of 3 – 17 years. Individuals must be a Strathcona County Resident and on the RAP program. Parents/Guardians will be provided a phone number to call to schedule an appointment for the child within five (5) business days. Date: (yyyy/mm/dd) Sports Equipment Request Name of child (First & Last) Date of Birth Type of equipment being requested* (yyyy/mm/dd) 1. ________________________ 2. 3. 4. * Please note: Full hockey requests also require proof of registration with Hockey Alberta sanctioned club or program. Contact person for this request: Parent/Guardian (please print) Phone Number Email: It is agreed and understood by all parties that the equipment is supplied “as is” and although Sport Central takes reasonable care, Sport Central, its members and volunteers cannot be held responsible for the performance, safety or any damages caused through the use of these items. Thank you for your support in helping our families meet their recreational needs. Sincerely, Strathcona County Representative Signature Job title Print name of above Contact number of above Collection and use of personal information Personal information is collected under the authority of section 33(c) of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act and will be shared with Sport Central in order to process your equipment requests. -

Santa Fe Bite Takes Nob Hill by Storm Page 12 Music:A River

VOLUME 28 | ISSUE 31 | AUGUST 1-7, 2019 | FREE 2019 1-7, AUGUST | 31 ISSUE | 28 VOLUME PHOTOGRAPHY BY NICK TAURO JR JR TAURO NICK BY PHOTOGRAPHY NONSTOP CLEANUP A RIVER, A BAND SANTA FE BITE TAKES POWERPACK AND THE GUITAR NOB HILL BY STORM NEWS: PAGES 6 AND 7 MUSIC:PAGE 27 FOOD: PAGE 12 IN A VAN DOWN BY THE RIVER SINCE 1992 SINCE RIVER THE BY DOWN VAN A IN [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI AUGUST 1-7, 2019 AUGUST 1-7, 2019 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 28 | ISSUE 31 | AUGUST 1-7, 2019 Email letters, including author’s name, mailing address and daytime phone number to [email protected]. Letters can also be mailed to P.O. Box 81, Albuquerque, N.M., 87103. Letters—including comments posted on alibi.com—may be EDITORIAL published in any medium and edited for length and clarity; owing to the volume of correspondence, we regrettably can’t MANAGING EDITOR/ FILM EDITOR: respond to every letter. Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC EDITOR/NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] Municipal Wells Ethylene dibromide is not a potent carcinogen FOOD EDITOR: unless you are a certain strain of rat or mouse. It’s Dan Pennington (Ext. 255) [email protected] Uncontaminated ARTS AND LIT.EDITOR: probably not a carcinogen in humans. After all, Clarke Condé (Ext. 239) [email protected] Dear Alibi, even the EPA acknowledges that it has COPY EDITOR: “inadequate evidence” from human studies to Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] The July 25 Kirtland fuel spill article by August CALENDARS EDITOR: March [v28 i30] quotes a representative of the show that EDB is carcinogenic in humans. -

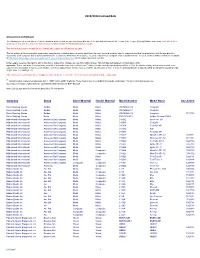

Approved Bats List

2015/2016 Licensed Bats 2016 Licensed 2 1/4" Bat List The following is a list of bats with a 2 1/4 inch maximum diameter that are currently licensed for use in the baseball divisions of Little League (Little League [Majors] Division and below). Bats with metal or wood barrels may also be used in the Junior League and Intermediate 50/70 Baseball Divisons of play. This list includes bats currently licensed with Little League as of February 22, 2016 This list includes all licensed models organized by manufacturer, including those composite barrel bats that have received a waiver from the composite-barreled bat moratorium. Little League placed a moratorium on all composite-barreled baseball bats for these divisions, which took effect on Dec. 30, 2010. A list of those composite-barreled bats that have received a waiver of that moratorium is available at http://www.littleleague.org/learn/equipment/licensedcompositebats.htm, which includes photos of each bat. Little League reserves the right to add to this list or make other changes as new information arises. This list was last updated on February 2, 2016. Important: This is only a list of licensed bats, not a list of all possible bats that could be used. Provided the bat meets the specifications of Rule 1.10 for the division of play, and provided the bat is not subject to the moratorium, it may be used. Any bat, even those appearing on this list, must meet all the specifications of Rule 1.10 for the particular division of play, including specifications regarding length, weight, diameter, markings, etc. -

Bid Award Report

June 04, 2014 EVANS-BRANT CSD Page 1 11:45:00 am Bid Award Detail Report Bid: 14-15 ATHLETICS ATHLETIC SUPPLIES & EQUIPMENT By Vendor/Item Unit of Item ID Description Quantity Unit Price Measure Total Bid Vendor Item ID Awarded 000496-ALUMINUM ATHLETIC EQUIPMENT Bid Order Address: (000496) ALUMINUM ATHLETIC EQUIPMENT 1000 ENTERPRISE DRIVE ROYERSFORD, PA 19468 00103 G400 Gill Essential Hurdles - FIRST TO THE FINISH 6.0000 70.0000 EA 420.00 SCAH-BK PAGE 8 Item Reference# G400 Totals for 000496-ALUMINUM ATHLETIC EQUIPMENT 1 Items $420.00 000916-JAMESTOWN CYCLE SHOP, INC. Bid Order Address: (000916) JAMESTOWN CYCLE SHOP, INC. 10 HARRISON ST. JAMESTOWN, NY 14701 00177 ST5 Rawlings Football Full Grain Leather (NO 7.0000 34.0000 EA 238.00 SUBSTITION) - RIDDELL, INC. Item Reference# ST5 00200 Wilson Evolution Official Basketball NO 4.0000 38.0000 EA 152.00 SUBSTITUTIONS - ANACONDA SPORTS Item Reference# B0516NL ADD-0000018 Pro V 1 Golf Balls Eagle Head Logo Art work to be 6.0000 50.0000 DZ 300.00 approved by Atheltic Director - LAUX SPORTING GOODS ADD-0000028 Adidas Tabela II Soccer Jersey Climalite 100% 30.0000 18.0000 EA 540.00 Polyester, Sizes: TBA, Color: Drk Green Numbers on front and back in white, imprinted on upper left front with school eagle head and " Lake Shore" all art work to be approved by Athletic Director - LAUX SPORTING GOODS ADD-0000029 Adidas Tabela II Soccer Jersey Climalite 100% 30.0000 18.0000 EA 540.00 Polyester, Color: White Numbers: Drk green on front and back, Imprinted with school eagle head and "Lake Shore" in upper left front All art work to be approved by Athletic Director. -

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions set by OQL-USA Writing Team For use in OQL USA LEAGUE matches during the week beginning December 14, 2020 Correct as of 12/14/2020 Round 1 1a What country singer and coach on "The Voice" reacted to being named People magazine's 2017 Sexiest Man Alive by saying, Blake SHELTON "Y'all must be running out of people"? 1b Who was the longest-serving Secretary of State in US History, serving under FDR from 1933-44? He was referred to as "the Cordell HULL Father of the United Nations" and won the Nobel Peace Prize. 2a Right on the North Carolina border, what highest point in Tennessee is also the highest mountain in the Great Smoky CLINGMANS DOME Mountains range? 2b Ventanarosa Productions is a production company founded by Salma HAYEK what Oscar-nominated Frida actress? 3a What eponymous creature is the largest wild animal in Equidae, the horse family? This endangered animal endemic to Kenya GREVY'S ZEBRA and Ethiopia is larger than the mountain and plains species of the same animal. 3b Painted by an artist who never visited the country, a ceiling mural that inaccurately depicts coffee growing at sea level -- not SAN JOSE, Costa Rica on mountains like Cerro Chiripo -- is a prominent feature of the Teatro Nacional in what Central American capital city? 4a Launch titles for the PlayStation 5 include a Spider-Man game MILES MORALES (prompt on with what subtitle, also the name of the main character in Into either word as the subtitle is the Spider-Verse? needed) 4b On its list of "15 Groundbreaking Debut Rap Albums Since Hip- Hop Was Born," The Source includes what 1997 album from SUPA DUPA FLY Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott? Round 2 1a Ric Flair's daughter Ashley is regarded as one of the greatest WWE Women's Champions of all time. -

Annual Review of Football Finance 2015 Sports Business Group 1 Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2015

Revolution Annual Review of Football Finance – Highlights Sports Business Group June 2015 Annual Review of Football Finance 2015 Sports Business Group 1 Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2015 Our first football finance report was produced in The following sections of the full report include June 1992, a couple of months ahead of the start of comprehensive data and analysis of the business drivers the inaugural Premier League season. For more than and financial trends for clubs in the top four divisions 20 years we have documented clubs’ business and of English football, with a particular focus on Premier commercial performance, striving to provide the most League and Championship clubs. The analysis covers comprehensive picture possible of English professional through to the end of the 2013/14 season and we also football’s finances, set within the context of the include some pointers to future financial results. regulatory environment and the wider European game. Revenue and profitability The Sports Business Group at Deloitte provides an Analysis of matchday, broadcasting and commercial in-depth analysis of football’s finances in its 52 page full revenue streams; Revenue projections to 2016/17; report, which includes: The financial impact of participation in UEFA club competitions, promotion and relegation; Operating Europe’s premier leagues results and pre-tax profits and losses; Average Scale of the overall European football market; attendances and stadium utilisation in the Premier Comprehensive data and analysis of trends for clubs in League and Football League. the ‘big five’ leagues including revenue breakdowns, wage costs, operating results, and match attendances; Wages and transfers Factors impacting on clubs’ future revenues; Key Analysis of clubs’ total wage costs; The relationship financial indicators for six more European leagues. -

The Irish Rugby Injury Surveillance Project

IRIS The Irish Rugby Injury Surveillance Project All-Ireland League Amateur Club Rugby 2018-2019 Season Report IRIS Authored by the Irish Rugby Injury Surveillance (IRIS) Project Steering Group IRFU: Dr. Rod McLoughlin (Medical Director, IRFU) Ms. Mairéad Liston (Medical Department Co-ordinator, IRFU) Principal Investigators: Dr. Tom Comyns (Strength and Conditioning, University of Limerick) Dr. Ian Kenny (Biomechanics, University of Limerick) Supporting Investigators: Dr. Róisín Cahalan (Doctoral Supervisor, Physiotherapy, University of Limerick) Dr. Mark Campbell (Doctoral Supervisor, Sport Psychology, University of Limerick) Prof. Liam Glynn (Graduate Entry Medicine, University of Limerick) Mr. Alan Griffin (Doctoral Researcher, Sport Sciences, University of Limerick) Prof. Drew Harrison (Biomechanics, University of Limerick) Ms. Therese Leahy (Doctoral Researcher, Physiotherapy, University of Limerick) Dr. Mark Lyons (Doctoral Supervisor, Strength and Conditioning, University of Limerick) Dr. Helen Purtill (Mathematics and Statistics, University of Limerick) Dr. Giles Warrington (Sport and Exercise Physiology, University of Limerick) Ms. Caithríona Yeomans (Doctoral Researcher, Physiotherapy, University of Limerick)* The authors would like to acknowledge with considerable gratitude, the work of the doctors, physiotherapists and club staff involved with the IRIS clubs who have recorded injury information throughout the project. *Report Primary Author (ii) Contents The IRIS team (ii) 4.4 Nature of Training Injuries 28 4.5 Training Injury -

Abdul-Aziz V. National Basketball Association Players' Pension Plan

Case 1:17-cv-08901 Document 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 of 27 1 Jason L. Melancon, Esq. (SBN 28152) Robert C. Rimes, Esq. (SBN 28740) 2 R. Lee Daquanno, Jr., Esq. (SBN 36430) 3 MELANCON | RIMES, LLC 6700 Jefferson Hwy., Building 6 4 Baton Rouge, LA 70806 Telephone: (225) 303-0455 5 Facsimile: (225) 303-0459 Email: [email protected] 6 7 Counsel for Plaintiff 8 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK 11 ZAID ABDUL-AZIZ, Individually No. CV 17-8901 12 And on behalf of all others similarly situated 13 Plaintiff, 14 CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE FEDERAL ERISA v. 15 LAWS NATIONAL BASKETBALL JURY TRIAL DEMANDED 16 ASSOCIATION PLAYERS’ PENSION PLAN 17 Defendant. 18 19 NATURE OF THE ACTION 20 1. This class action complaint is filed individually and on behalf of a class consisting 21 of all former participants in the National Basketball Association Players’ Pension Plan (the 22 “Plan”), who elected to receive a form of retirement pension that terminated prior to the player or 23 24 his spouse’s death, if applicable, seeking a declaration that the Plan, a defined benefit pension 25 plan, violates the Sections 204(c)(3) and 502(a)(1)(B) of the Employee Retirement Income 26 Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”), and further seeking injunctive relief requiring the Plan to 27 recalculate and remit pension benefits in accordance with ERISA and IRS Code regulations. 28 1 Case 1:17-cv-08901 Document 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 2 of 27 1 JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2 2. -

To Download Bray Wanderers V Cork City Matchday

Seagull Scene SSE Airtricity League First Division Season 2021 Vol. 37 No. 3 WELCOME TO THE CARLISLE BRAY WANDERERS FC I would like to welcome Colin Healy and his Cork City team and club officials to the Carlisle Grounds for this ROLL OF HONOUR evening’s encounter. FAI Cup Winners (2) Both teams lie in the bottom half of the table going into this game. Wanderers have drawn four and lost once 1990, 1999 while Cork have lost their last four league games. First Division Champions (3) Wanderers have had a bit of an injury crisis so far, 1985/86, 1995/96, 1999/00 particularly amongst the forwards, where Gary Shaw First Division runners-up (2) and Darragh Lynch have both been missed. Lynch has yet to feature this season. 1990/91, 1997/98 On the plus side it was great to see Charlie Gallagher Shield Winners (1) make his first team debut in Cobh last week. Charlie is 1995/96 the latest player to come through the Academy ranks at Bray to play for the first team. Charlie was top scorer for National League B Division Champions (2) the under 17s last season. 1991/92, 1998/99 Our Academy teams returned to training this week in Enda McGuill Cup (1) preparation for the season. Only teams up to under 18 2005 can train now so the under 19s must wait a bit longer to resume training. FAI Intermediate Cup Winners (2) 1955/56, 1957/58 The viewing figures for the live streaming service of Bray Wanderers two home games so far this season FAI Junior Cup Winners (2) have been quite good. -

In Amateur Rugby Union Irfu Guide To

IRFU GUIDE TO IN AMATEUR RUGBY UNION THE AIM OF THIS BROCHURE IS TO PROVIDE INFORMATION ON CONCUSSION TO THOSE INVOLVED IN RUGBY UNION IN IRELAND. > Concussion MUST be taken extremely seriously. > Any player with a suspected concussion MUST be removed immediately from training/play and not return. > They MUST complete the Graduated Return to Play Protocol. > Concussion is treatable. RECOGNISE AND REMOVE PAGE 1 WHAT IS CONCUSSION? Sports related concussion is a traumatic brain injury that is caused by a direct force to the head or a force elsewhere in the body which is transmitted to the head. Concussion results in temporary impairment of brain function. However, in some cases, signs and symptoms evolve over a number of minutes to hours. What causes it? Concussion can be caused by a blow to the head or from a whiplash type movement of the head and neck that can occur when a player is tackled or collides with another player or the ground. Concussion Facts: > You do not have to lose consciousness to suffer from a concussion. > The effects of concussion cannot be seen on standard x-ray, CT scan or MRI. > Concussion can occur in a game or at training. > The onset of the effects of concussion may be delayed for up to 24–48 hours. > Symptoms generally resolve over a period of days or weeks but in some cases can be more prolonged. > Most doctors would argue that the physical benefits of taking part in contact sports outweigh the potential risks associated with sports related concussion. Concussion is treatable. -

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2019/02 TRIBUNAL ARBITRAL DU SPORT/COURT OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT __________________________________________________________________ Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2019/2 Lausanne 2019 Table des matières/Table of Contents Editorial ………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Articles et commentaires / Articles and Commentaries ....................................................................... 6 CAS procedures and their efficiency Laurence Boisson de Chazournes & Ségolène Couturier ................................................................. 7 Aperçu du nouveau Code disciplinaire FIFA 2019 Estelle de La Rochefoucauld ............................................................................................................... 18 Sports arbitration ex aequo et bono: basketball as a groundbreaker Hubert Radke ........................................................................................................................................ 25 Jurisprudence majeure / Leading Cases ................................................................................................ 52 CAS 2018/A/5580 Blagovest Krasimirov Bozhinovski v. Anti-Doping Centre of the Republic of Bulgaria (ADC) & Bulgarian Olympic Committee (BOC) 8 March 2019 ......................................................................................................................................... 53 CAS 2018/A/5607 SA Royal Sporting Club Anderlecht (RSCA) v. Matías Ezequiel Suárez & Club Atlético Belgrano de Córdoba (CA Belgrano) & CAS 2018/A/5608