The Neglected Giant: Agnes Meyer Driscoll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middleware in Action 2007

Technology Assessment from Ken North Computing, LLC Middleware in Action Industrial Strength Data Access May 2007 Middleware in Action: Industrial Strength Data Access Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Mature Technology .........................................................................................................3 Scalability, Interoperability, High Availability ...................................................................5 Components, XML and Services-Oriented Architecture..................................................6 Best-of-Breed Middleware...............................................................................................7 Pay Now or Pay Later .....................................................................................................7 2.0 Architectures for Distributed Computing.................................................................. 8 2.1 Leveraging Infrastructure ........................................................................................ 8 2.2 Multi-Tier, N-Tier Architecture ................................................................................. 9 2.3 Persistence, Client-Server Databases, Distributed Data ....................................... 10 Client-Server SQL Processing ......................................................................................10 Client Libraries .............................................................................................................. -

A Practical Attack on Broadcast RC4

A Practical Attack on Broadcast RC4 Itsik Mantin and Adi Shamir Computer Science Department, The Weizmann Institute, Rehovot 76100, Israel. {itsik,shamir}@wisdom.weizmann.ac.il Abstract. RC4is the most widely deployed stream cipher in software applications. In this paper we describe a major statistical weakness in RC4, which makes it trivial to distinguish between short outputs of RC4 and random strings by analyzing their second bytes. This weakness can be used to mount a practical ciphertext-only attack on RC4in some broadcast applications, in which the same plaintext is sent to multiple recipients under different keys. 1 Introduction A large number of stream ciphers were proposed and implemented over the last twenty years. Most of these ciphers were based on various combinations of linear feedback shift registers, which were easy to implement in hardware, but relatively slow in software. In 1987Ron Rivest designed the RC4 stream cipher, which was based on a different and more software friendly paradigm. It was integrated into Microsoft Windows, Lotus Notes, Apple AOCE, Oracle Secure SQL, and many other applications, and has thus become the most widely used software- based stream cipher. In addition, it was chosen to be part of the Cellular Digital Packet Data specification. Its design was kept a trade secret until 1994, when someone anonymously posted its source code to the Cypherpunks mailing list. The correctness of this unofficial description was confirmed by comparing its outputs to those produced by licensed implementations. RC4 has a secret internal state which is a permutation of all the N =2n possible n bits words. -

Historical Ciphers • A

ECE 646 - Lecture 6 Required Reading • W. Stallings, Cryptography and Network Security, Chapter 2, Classical Encryption Techniques Historical Ciphers • A. Menezes et al., Handbook of Applied Cryptography, Chapter 7.3 Classical ciphers and historical development Why (not) to study historical ciphers? Secret Writing AGAINST FOR Steganography Cryptography (hidden messages) (encrypted messages) Not similar to Basic components became modern ciphers a part of modern ciphers Under special circumstances modern ciphers can be Substitution Transposition Long abandoned Ciphers reduced to historical ciphers Transformations (change the order Influence on world events of letters) Codes Substitution The only ciphers you Ciphers can break! (replace words) (replace letters) Selected world events affected by cryptology Mary, Queen of Scots 1586 - trial of Mary Queen of Scots - substitution cipher • Scottish Queen, a cousin of Elisabeth I of England • Forced to flee Scotland by uprising against 1917 - Zimmermann telegram, America enters World War I her and her husband • Treated as a candidate to the throne of England by many British Catholics unhappy about 1939-1945 Battle of England, Battle of Atlantic, D-day - a reign of Elisabeth I, a Protestant ENIGMA machine cipher • Imprisoned by Elisabeth for 19 years • Involved in several plots to assassinate Elisabeth 1944 – world’s first computer, Colossus - • Put on trial for treason by a court of about German Lorenz machine cipher 40 noblemen, including Catholics, after being implicated in the Babington Plot by her own 1950s – operation Venona – breaking ciphers of soviet spies letters sent from prison to her co-conspirators stealing secrets of the U.S. atomic bomb in the encrypted form – one-time pad 1 Mary, Queen of Scots – cont. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 21-10527-JTD Doc 285 Filed 04/14/21 Page 1 of 68 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CARBONLITE HOLDINGS LLC, et al.,1 ) Case No. 21-10527 (JTD) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Victoria X. Tran, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On April 10, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: Notice of Proposed Sale or Sales of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets, Free and Clear of All Encumbrances, Other Than Assumed Liabilities, and Scheduling Final Sale Hearing Related Thereto (Docket No. 268) Notice of Proposed Assumption and Assignment of Designated Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases (Docket No. 269) Furthermore, on April 10, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit D: Notice of Proposed Sale or Sales of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets, Free and Clear of All Encumbrances, Other Than Assumed Liabilities, and Scheduling Final Sale Hearing Related Thereto (Docket No. 268, Pages 1-4) Notice of Proposed Assumption and Assignment of Designated Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases (Docket No. -

Cryptanalysis of Stream Ciphers Based on Arrays and Modular Addition

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN FACULTEIT INGENIEURSWETENSCHAPPEN DEPARTEMENT ELEKTROTECHNIEK{ESAT Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Leuven-Heverlee Cryptanalysis of Stream Ciphers Based on Arrays and Modular Addition Promotor: Proefschrift voorgedragen tot Prof. Dr. ir. Bart Preneel het behalen van het doctoraat in de ingenieurswetenschappen door Souradyuti Paul November 2006 KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN FACULTEIT INGENIEURSWETENSCHAPPEN DEPARTEMENT ELEKTROTECHNIEK{ESAT Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Leuven-Heverlee Cryptanalysis of Stream Ciphers Based on Arrays and Modular Addition Jury: Proefschrift voorgedragen tot Prof. Dr. ir. Etienne Aernoudt, voorzitter het behalen van het doctoraat Prof. Dr. ir. Bart Preneel, promotor in de ingenieurswetenschappen Prof. Dr. ir. Andr´eBarb´e door Prof. Dr. ir. Marc Van Barel Prof. Dr. ir. Joos Vandewalle Souradyuti Paul Prof. Dr. Lars Knudsen (Technical University, Denmark) U.D.C. 681.3*D46 November 2006 ⃝c Katholieke Universiteit Leuven { Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen Arenbergkasteel, B-3001 Heverlee (Belgium) Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm, elektron- isch of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. D/2006/7515/88 ISBN 978-90-5682-754-0 To my parents for their unyielding ambition to see me educated and Prof. Bimal Roy for making cryptology possible in my life ... My Gratitude It feels awkward to claim the thesis to be singularly mine as a great number of people, directly or indirectly, participated in the process to make it see the light of day. -

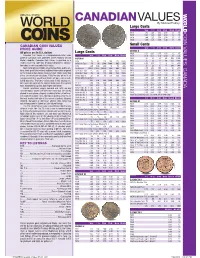

*UPDATED Canadian Values 07-04 201 7/26/2016 4:42:21 PM *UPDATED Canadian Values 07-04 202 COIN VALUES: CANADA 02 .0 .0 12

CANADIAN VALUES By Michael Findlay Large Cents VG-8 F-12 VF-20 EF-40 MS-60 MS-63R 1917 1.00 1.25 1.50 2.50 13. 45. CANADA COIN VALUES: 1918 1.00 1.25 1.50 2.50 13. 45. 1919 1.00 1.25 1.50 2.50 13. 45. 1920 1.00 1.25 1.50 3.00 18. 70. CANADIAN COIN VALUES Small Cents PRICE GUIDE VG-8 F-12 VF-20 EF-40 MS-60 MS-63R GEORGE V All prices are in U.S. dollars LargeL Cents C t 1920 0.20 0.35 0.75 1.50 12. 45. Canadian Coin Values is a comprehensive retail value VG-8 F-12 VF-20 EF-40 MS-60 MS-63R 1921 0.50 0.75 1.50 4.00 30. 250. guide of Canadian coins published online regularly at Coin VICTORIA 1922 20. 23. 28. 40. 200. 1200. World’s website. Canadian Coin Values is provided as a 1858 70. 90. 120. 200. 475. 1800. 1923 30. 33. 42. 55. 250. 2000. reader service to collectors desiring independent informa- 1858 Coin Turn NI NI 2500. 5000. BNE BNE 1924 6.00 8.00 11. 16. 120. 800. tion about a coin’s potential retail value. 1859 4.00 5.00 6.00 10. 50. 200. 1925 25. 28. 35. 45. 200. 900. Sources for pricing include actual transactions, public auc- 1859 Brass 16000. 22000. 30000. BNE BNE BNE 1926 3.50 4.50 7.00 12. 90. 650. tions, fi xed-price lists and any additional information acquired 1859 Dbl P 9 #1 225. -

Security Evaluation of the K2 Stream Cipher

Security Evaluation of the K2 Stream Cipher Editors: Andrey Bogdanov, Bart Preneel, and Vincent Rijmen Contributors: Andrey Bodganov, Nicky Mouha, Gautham Sekar, Elmar Tischhauser, Deniz Toz, Kerem Varıcı, Vesselin Velichkov, and Meiqin Wang Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Department of Electrical Engineering ESAT/SCD-COSIC Interdisciplinary Institute for BroadBand Technology (IBBT) Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, bus 2446 B-3001 Leuven-Heverlee, Belgium Version 1.1 | 7 March 2011 i Security Evaluation of K2 7 March 2011 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Linear Attacks 3 2.1 Overview . 3 2.2 Linear Relations for FSR-A and FSR-B . 3 2.3 Linear Approximation of the NLF . 5 2.4 Complexity Estimation . 5 3 Algebraic Attacks 6 4 Correlation Attacks 10 4.1 Introduction . 10 4.2 Combination Generators and Linear Complexity . 10 4.3 Description of the Correlation Attack . 11 4.4 Application of the Correlation Attack to KCipher-2 . 13 4.5 Fast Correlation Attacks . 14 5 Differential Attacks 14 5.1 Properties of Components . 14 5.1.1 Substitution . 15 5.1.2 Linear Permutation . 15 5.2 Key Ideas of the Attacks . 18 5.3 Related-Key Attacks . 19 5.4 Related-IV Attacks . 20 5.5 Related Key/IV Attacks . 21 5.6 Conclusion and Remarks . 21 6 Guess-and-Determine Attacks 25 6.1 Word-Oriented Guess-and-Determine . 25 6.2 Byte-Oriented Guess-and-Determine . 27 7 Period Considerations 28 8 Statistical Properties 29 9 Distinguishing Attacks 31 9.1 Preliminaries . 31 9.2 Mod n Cryptanalysis of Weakened KCipher-2 . 32 9.2.1 Other Reduced Versions of KCipher-2 . -

Polish Mathematicians Finding Patterns in Enigma Messages

Fall 2006 Chris Christensen MAT/CSC 483 Machine Ciphers Polyalphabetic ciphers are good ways to destroy the usefulness of frequency analysis. Implementation can be a problem, however. The key to a polyalphabetic cipher specifies the order of the ciphers that will be used during encryption. Ideally there would be as many ciphers as there are letters in the plaintext message and the ordering of the ciphers would be random – an one-time pad. More commonly, some rotation among a small number of ciphers is prescribed. But, rotating among a small number of ciphers leads to a period, which a cryptanalyst can exploit. Rotating among a “large” number of ciphers might work, but that is hard to do by hand – there is a high probability of encryption errors. Maybe, a machine. During World War II, all the Allied and Axis countries used machine ciphers. The United States had SIGABA, Britain had TypeX, Japan had “Purple,” and Germany (and Italy) had Enigma. SIGABA http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIGABA 1 A TypeX machine at Bletchley Park. 2 From the 1920s until the 1970s, cryptology was dominated by machine ciphers. What the machine ciphers typically did was provide a mechanical way to rotate among a large number of ciphers. The rotation was not random, but the large number of ciphers that were available could prevent depth from occurring within messages and (if the machines were used properly) among messages. We will examine Enigma, which was broken by Polish mathematicians in the 1930s and by the British during World War II. The Japanese Purple machine, which was used to transmit diplomatic messages, was broken by William Friedman’s cryptanalysts. -

The the Enigma Enigma Machinemachine

TheThe EnigmaEnigma MachineMachine History of Computing December 6, 2006 Mike Koss Invention of Enigma ! Invented by Arthur Scherbius, 1918 ! Adopted by German Navy, 1926 ! Modified military version, 1930 ! Two Additional rotors added, 1938 How Enigma Works Scrambling Letters ! Each letter on the keyboard is connected to a lamp letter that depends on the wiring and position of the rotors in the machine. ! Right rotor turns before each letter. How to Use an Enigma ! Daily Setup – Secret settings distributed in code books. ! Encoding/Decoding a Message Setup: Select (3) Rotors ! We’ll use I-II-III Setup: Rotor Ring Settings ! We’ll use A-A-A (or 1-1-1). Rotor Construction Setup: Plugboard Settings ! We won’t use any for our example (6 to 10 plugs were typical). Setup: Initial Rotor Position ! We’ll use “M-I-T” (or 13-9-20). Encoding: Pick a “Message Key” ! Select a 3-letter key (or indicator) “at random” (left to the operator) for this message only. ! Say, I choose “M-C-K” (or 13-3-11 if wheels are printed with numbers rather than letters). Encoding: Transmit the Indicator ! Germans would transmit the indicator by encoding it using the initial (daily) rotor position…and they sent it TWICE to make sure it was received properly. ! E.g., I would begin my message with “MCK MCK”. ! Encoded with the daily setting, this becomes: “NWD SHE”. Encoding: Reset Rotors ! Now set our rotors do our chosen message key “M-C-K” (13-3-11). ! Type body of message: “ENIGMA REVEALED” encodes to “QMJIDO MZWZJFJR”. -

Analysis of Lightweight Stream Ciphers

ANALYSIS OF LIGHTWEIGHT STREAM CIPHERS THÈSE NO 4040 (2008) PRÉSENTÉE LE 18 AVRIL 2008 À LA FACULTÉ INFORMATIQUE ET COMMUNICATIONS LABORATOIRE DE SÉCURITÉ ET DE CRYPTOGRAPHIE PROGRAMME DOCTORAL EN INFORMATIQUE, COMMUNICATIONS ET INFORMATION ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE POUR L'OBTENTION DU GRADE DE DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES PAR Simon FISCHER M.Sc. in physics, Université de Berne de nationalité suisse et originaire de Olten (SO) acceptée sur proposition du jury: Prof. M. A. Shokrollahi, président du jury Prof. S. Vaudenay, Dr W. Meier, directeurs de thèse Prof. C. Carlet, rapporteur Prof. A. Lenstra, rapporteur Dr M. Robshaw, rapporteur Suisse 2008 F¨ur Philomena Abstract Stream ciphers are fast cryptographic primitives to provide confidentiality of electronically transmitted data. They can be very suitable in environments with restricted resources, such as mobile devices or embedded systems. Practical examples are cell phones, RFID transponders, smart cards or devices in sensor networks. Besides efficiency, security is the most important property of a stream cipher. In this thesis, we address cryptanalysis of modern lightweight stream ciphers. We derive and improve cryptanalytic methods for dif- ferent building blocks and present dedicated attacks on specific proposals, including some eSTREAM candidates. As a result, we elaborate on the design criteria for the develop- ment of secure and efficient stream ciphers. The best-known building block is the linear feedback shift register (LFSR), which can be combined with a nonlinear Boolean output function. A powerful type of attacks against LFSR-based stream ciphers are the recent algebraic attacks, these exploit the specific structure by deriving low degree equations for recovering the secret key. -

The Battle Over Pearl Harbor: the Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1995 The Battle Over Pearl Harbor: The Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994 Robert Seifert Hamblet College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hamblet, Robert Seifert, "The Battle Over Pearl Harbor: The Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994" (1995). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625993. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5zq1-1y76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BATTLE OVER PEARL HARBOR The Controversy Surrounding the Japanese Attack, 1941-1994 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Robert S. Hamblet 1995 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts '-{H JxijsJr 1. Author Approved, November 1995 d(P — -> Edward P. CrapoII Edward E. Pratt TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................iv ABSTRACT..............................................................................................v -

Cryptology: an Historical Introduction DRAFT

Cryptology: An Historical Introduction DRAFT Jim Sauerberg February 5, 2013 2 Copyright 2013 All rights reserved Jim Sauerberg Saint Mary's College Contents List of Figures 8 1 Caesar Ciphers 9 1.1 Saint Cyr Slide . 12 1.2 Running Down the Alphabet . 14 1.3 Frequency Analysis . 15 1.4 Linquist's Method . 20 1.5 Summary . 22 1.6 Topics and Techniques . 22 1.7 Exercises . 23 2 Cryptologic Terms 29 3 The Introduction of Numbers 31 3.1 The Remainder Operator . 33 3.2 Modular Arithmetic . 38 3.3 Decimation Ciphers . 40 3.4 Deciphering Decimation Ciphers . 42 3.5 Multiplication vs. Addition . 44 3.6 Koblitz's Kid-RSA and Public Key Codes . 44 3.7 Summary . 48 3.8 Topics and Techniques . 48 3.9 Exercises . 49 4 The Euclidean Algorithm 55 4.1 Linear Ciphers . 55 4.2 GCD's and the Euclidean Algorithm . 56 4.3 Multiplicative Inverses . 59 4.4 Deciphering Decimation and Linear Ciphers . 63 4.5 Breaking Decimation and Linear Ciphers . 65 4.6 Summary . 67 4.7 Topics and Techniques . 67 4.8 Exercises . 68 3 4 CONTENTS 5 Monoalphabetic Ciphers 71 5.1 Keyword Ciphers . 72 5.2 Keyword Mixed Ciphers . 73 5.3 Keyword Transposed Ciphers . 74 5.4 Interrupted Keyword Ciphers . 75 5.5 Frequency Counts and Exhaustion . 76 5.6 Basic Letter Characteristics . 77 5.7 Aristocrats . 78 5.8 Summary . 80 5.9 Topics and Techniques . 81 5.10 Exercises . 81 6 Decrypting Monoalphabetic Ciphers 89 6.1 Letter Interactions . 90 6.2 Decrypting Monoalphabetic Ciphers .