A History of Syntax Isaac Quinn Dupont Facult

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middleware in Action 2007

Technology Assessment from Ken North Computing, LLC Middleware in Action Industrial Strength Data Access May 2007 Middleware in Action: Industrial Strength Data Access Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Mature Technology .........................................................................................................3 Scalability, Interoperability, High Availability ...................................................................5 Components, XML and Services-Oriented Architecture..................................................6 Best-of-Breed Middleware...............................................................................................7 Pay Now or Pay Later .....................................................................................................7 2.0 Architectures for Distributed Computing.................................................................. 8 2.1 Leveraging Infrastructure ........................................................................................ 8 2.2 Multi-Tier, N-Tier Architecture ................................................................................. 9 2.3 Persistence, Client-Server Databases, Distributed Data ....................................... 10 Client-Server SQL Processing ......................................................................................10 Client Libraries .............................................................................................................. -

A Practical Attack on Broadcast RC4

A Practical Attack on Broadcast RC4 Itsik Mantin and Adi Shamir Computer Science Department, The Weizmann Institute, Rehovot 76100, Israel. {itsik,shamir}@wisdom.weizmann.ac.il Abstract. RC4is the most widely deployed stream cipher in software applications. In this paper we describe a major statistical weakness in RC4, which makes it trivial to distinguish between short outputs of RC4 and random strings by analyzing their second bytes. This weakness can be used to mount a practical ciphertext-only attack on RC4in some broadcast applications, in which the same plaintext is sent to multiple recipients under different keys. 1 Introduction A large number of stream ciphers were proposed and implemented over the last twenty years. Most of these ciphers were based on various combinations of linear feedback shift registers, which were easy to implement in hardware, but relatively slow in software. In 1987Ron Rivest designed the RC4 stream cipher, which was based on a different and more software friendly paradigm. It was integrated into Microsoft Windows, Lotus Notes, Apple AOCE, Oracle Secure SQL, and many other applications, and has thus become the most widely used software- based stream cipher. In addition, it was chosen to be part of the Cellular Digital Packet Data specification. Its design was kept a trade secret until 1994, when someone anonymously posted its source code to the Cypherpunks mailing list. The correctness of this unofficial description was confirmed by comparing its outputs to those produced by licensed implementations. RC4 has a secret internal state which is a permutation of all the N =2n possible n bits words. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 21-10527-JTD Doc 285 Filed 04/14/21 Page 1 of 68 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CARBONLITE HOLDINGS LLC, et al.,1 ) Case No. 21-10527 (JTD) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Victoria X. Tran, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On April 10, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: Notice of Proposed Sale or Sales of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets, Free and Clear of All Encumbrances, Other Than Assumed Liabilities, and Scheduling Final Sale Hearing Related Thereto (Docket No. 268) Notice of Proposed Assumption and Assignment of Designated Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases (Docket No. 269) Furthermore, on April 10, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit D: Notice of Proposed Sale or Sales of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets, Free and Clear of All Encumbrances, Other Than Assumed Liabilities, and Scheduling Final Sale Hearing Related Thereto (Docket No. 268, Pages 1-4) Notice of Proposed Assumption and Assignment of Designated Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases (Docket No. -

Cryptanalysis of Stream Ciphers Based on Arrays and Modular Addition

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN FACULTEIT INGENIEURSWETENSCHAPPEN DEPARTEMENT ELEKTROTECHNIEK{ESAT Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Leuven-Heverlee Cryptanalysis of Stream Ciphers Based on Arrays and Modular Addition Promotor: Proefschrift voorgedragen tot Prof. Dr. ir. Bart Preneel het behalen van het doctoraat in de ingenieurswetenschappen door Souradyuti Paul November 2006 KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN FACULTEIT INGENIEURSWETENSCHAPPEN DEPARTEMENT ELEKTROTECHNIEK{ESAT Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Leuven-Heverlee Cryptanalysis of Stream Ciphers Based on Arrays and Modular Addition Jury: Proefschrift voorgedragen tot Prof. Dr. ir. Etienne Aernoudt, voorzitter het behalen van het doctoraat Prof. Dr. ir. Bart Preneel, promotor in de ingenieurswetenschappen Prof. Dr. ir. Andr´eBarb´e door Prof. Dr. ir. Marc Van Barel Prof. Dr. ir. Joos Vandewalle Souradyuti Paul Prof. Dr. Lars Knudsen (Technical University, Denmark) U.D.C. 681.3*D46 November 2006 ⃝c Katholieke Universiteit Leuven { Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen Arenbergkasteel, B-3001 Heverlee (Belgium) Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm, elektron- isch of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. D/2006/7515/88 ISBN 978-90-5682-754-0 To my parents for their unyielding ambition to see me educated and Prof. Bimal Roy for making cryptology possible in my life ... My Gratitude It feels awkward to claim the thesis to be singularly mine as a great number of people, directly or indirectly, participated in the process to make it see the light of day. -

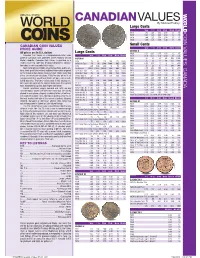

*UPDATED Canadian Values 07-04 201 7/26/2016 4:42:21 PM *UPDATED Canadian Values 07-04 202 COIN VALUES: CANADA 02 .0 .0 12

CANADIAN VALUES By Michael Findlay Large Cents VG-8 F-12 VF-20 EF-40 MS-60 MS-63R 1917 1.00 1.25 1.50 2.50 13. 45. CANADA COIN VALUES: 1918 1.00 1.25 1.50 2.50 13. 45. 1919 1.00 1.25 1.50 2.50 13. 45. 1920 1.00 1.25 1.50 3.00 18. 70. CANADIAN COIN VALUES Small Cents PRICE GUIDE VG-8 F-12 VF-20 EF-40 MS-60 MS-63R GEORGE V All prices are in U.S. dollars LargeL Cents C t 1920 0.20 0.35 0.75 1.50 12. 45. Canadian Coin Values is a comprehensive retail value VG-8 F-12 VF-20 EF-40 MS-60 MS-63R 1921 0.50 0.75 1.50 4.00 30. 250. guide of Canadian coins published online regularly at Coin VICTORIA 1922 20. 23. 28. 40. 200. 1200. World’s website. Canadian Coin Values is provided as a 1858 70. 90. 120. 200. 475. 1800. 1923 30. 33. 42. 55. 250. 2000. reader service to collectors desiring independent informa- 1858 Coin Turn NI NI 2500. 5000. BNE BNE 1924 6.00 8.00 11. 16. 120. 800. tion about a coin’s potential retail value. 1859 4.00 5.00 6.00 10. 50. 200. 1925 25. 28. 35. 45. 200. 900. Sources for pricing include actual transactions, public auc- 1859 Brass 16000. 22000. 30000. BNE BNE BNE 1926 3.50 4.50 7.00 12. 90. 650. tions, fi xed-price lists and any additional information acquired 1859 Dbl P 9 #1 225. -

An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext

An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext By Isaac Quinn DuPont A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Isaac Quinn DuPont 2017 ii An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext Isaac Quinn DuPont Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2017 Abstract Tis dissertation is an archeological study of cryptography. It questions the validity of thinking about cryptography in familiar, instrumentalist terms, and instead reveals the ways that cryptography can been understood as writing, media, and computation. In this dissertation, I ofer a critique of the prevailing views of cryptography by tracing a number of long overlooked themes in its history, including the development of artifcial languages, machine translation, media, code, notation, silence, and order. Using an archeological method, I detail historical conditions of possibility and the technical a priori of cryptography. Te conditions of possibility are explored in three parts, where I rhetorically rewrite the conventional terms of art, namely, plaintext, encryption, and ciphertext. I argue that plaintext has historically been understood as kind of inscription or form of writing, and has been associated with the development of artifcial languages, and used to analyze and investigate the natural world. I argue that the technical a priori of plaintext, encryption, and ciphertext is constitutive of the syntactic iii and semantic properties detailed in Nelson Goodman’s theory of notation, as described in his Languages of Art. I argue that encryption (and its reverse, decryption) are deterministic modes of transcription, which have historically been thought of as the medium between plaintext and ciphertext. -

Data Extraction Tool

ANALYSIS OF COMMUNICATION PROTOCOLS FOR HOME AREA NETWORKS FOR SMART GRID Mayur Anand B.E, Visveswaraiah Technological University, Karnataka, India, 2007 PROJECT Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in COMPUTER SCIENCE at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2011 ANALYSIS OF COMMUNICATION PROTOCOLS FOR HOME AREA NETWORKS FOR SMART GRID A Project by Mayur Anand Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Isaac Ghansah, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Chung-E-Wang, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Mayur Anand I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the Project. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ________________ Nikrouz Faroughi, Ph.D. Date Department of Computer Science iii Abstract of ANALYSIS OF COMMUNICATION PROTOCOLS FOR HOME AREA NETWORKS FOR SMART GRID by Mayur Anand This project discusses home area networks in Smart Grid. A Home Area Network plays a very important role in communication among various devices in a home. There are multiple technologies that are in contention to be used to implement home area networks. This project analyses various communication protocols in Home Area Networks and their corressponding underlying standards in detail. The protocols and standards covered in this project are ZigBee, Z-Wave, IEEE 802.15.4 and IEEE 802.11. Only wireless protocols have been discussed and evaluated. Various security threats present in the protocols mentioned above along with the counter measures to most of the threats have been discussed as well. -

Improved Correlation Attacks on SOSEMANUK and SOBER-128

Improved Correlation Attacks on SOSEMANUK and SOBER-128 Joo Yeon Cho Helsinki University of Technology Department of Information and Computer Science, Espoo, Finland 24th March 2009 1 / 35 SOSEMANUK Attack Approximations SOBER-128 Outline SOSEMANUK Attack Method Searching Linear Approximations SOBER-128 2 / 35 SOSEMANUK Attack Approximations SOBER-128 SOSEMANUK (from Wiki) • A software-oriented stream cipher designed by Come Berbain, Olivier Billet, Anne Canteaut, Nicolas Courtois, Henri Gilbert, Louis Goubin, Aline Gouget, Louis Granboulan, Cedric` Lauradoux, Marine Minier, Thomas Pornin and Herve` Sibert. • One of the final four Profile 1 (software) ciphers selected for the eSTREAM Portfolio, along with HC-128, Rabbit, and Salsa20/12. • Influenced by the stream cipher SNOW and the block cipher Serpent. • The cipher key length can vary between 128 and 256 bits, but the guaranteed security is only 128 bits. • The name means ”snow snake” in the Cree Indian language because it depends both on SNOW and Serpent. 3 / 35 SOSEMANUK Attack Approximations SOBER-128 Overview 4 / 35 SOSEMANUK Attack Approximations SOBER-128 Structure 1. The states of LFSR : s0,..., s9 (320 bits) −1 st+10 = st+9 ⊕ α st+3 ⊕ αst, t ≥ 1 where α is a root of the primitive polynomial. 2. The Finite State Machine (FSM) : R1 and R2 R1t+1 = R2t ¢ (rtst+9 ⊕ st+2) R2t+1 = Trans(R1t) ft = (st+9 ¢ R1t) ⊕ R2t where rt denotes the least significant bit of R1t. F 3. The trans function Trans on 232 : 32 Trans(R1t) = (R1t × 0x54655307 mod 2 )≪7 4. The output of the FSM : (zt+3, zt+2, zt+1, zt)= Serpent1(ft+3, ft+2, ft+1, ft)⊕(st+3, st+2, st+1, st) 5 / 35 SOSEMANUK Attack Approximations SOBER-128 Previous Attacks • Authors state that ”No linear relation holds after applying Serpent1 and there are too many unknown bits...”. -

"Knowledge Will Be Manifold": Daniel 12.4 and the Idea of Intellectual Progress in the Middle Ages J

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University History Faculty Publications History Department 2014 "Knowledge Will Be Manifold": Daniel 12.4 and the Idea of Intellectual Progress in the Middle Ages J. R. Webb Bridgewater State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/history_fac Part of the History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Virtual Commons Citation Webb, J. R. (2014). "Knowledge Will Be Manifold": Daniel 12.4 and the Idea of Intellectual Progress in the Middle Ages. In History Faculty Publications. Paper 38. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/history_fac/38 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. “Knowledge Will Be Manifold”: Daniel 12.4 and the Idea of Intellectual Progress in the Middle Ages By J. R. Webb Je l’offre [ce livre] surtout a` mes critiques, a` ceux qui voudront bien le corriger, l’ameliorer,´ le refaire, le mettre au niveau des progres` ulterieurs´ de la science. “Plurimi pertransibunt, et multiplex erit scientia.” (Jules Michelet, Histoire de France, 1, 1833) Thus wrote Michelet to open his monumental history of France. By deploying this prophetic line from the book of Daniel in support of a positivistic approach to historical science, he was participating in a discourse on this perplexing passage that spanned nearly two millennia. He perhaps surmised this, though he probably did not know how deeply the passage penetrated into the intellectual tradition of the West or that he was favoring one interpretation of it over another.1 It is the trajectory of the interpretations of Daniel 12.4 in the Latin West from their first formulation in late antiquity that concerns the present exploration. -

Answers to Exercises

Answers to Exercises A bird does not sing because he has an answer, he sings because he has a song. —Chinese Proverb Intro.1: abstemious, abstentious, adventitious, annelidous, arsenious, arterious, face- tious, sacrilegious. Intro.2: When a software house has a popular product they tend to come up with new versions. A user can update an old version to a new one, and the update usually comes as a compressed file on a floppy disk. Over time the updates get bigger and, at a certain point, an update may not fit on a single floppy. This is why good compression is important in the case of software updates. The time it takes to compress and decompress the update is unimportant since these operations are typically done just once. Recently, software makers have taken to providing updates over the Internet, but even in such cases it is important to have small files because of the download times involved. 1.1: (1) ask a question, (2) absolutely necessary, (3) advance warning, (4) boiling hot, (5) climb up, (6) close scrutiny, (7) exactly the same, (8) free gift, (9) hot water heater, (10) my personal opinion, (11) newborn baby, (12) postponed until later, (13) unexpected surprise, (14) unsolved mysteries. 1.2: A reasonable way to use them is to code the five most-common strings in the text. Because irreversible text compression is a special-purpose method, the user may know what strings are common in any particular text to be compressed. The user may specify five such strings to the encoder, and they should also be written at the start of the output stream, for the decoder’s use. -

Talking Book Topics July-August 2017

Talking Book Topics July–August 2017 Volume 83, Number 4 About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics is published bimonthly in audio, large-print, and online formats and distributed at no cost to participants in the Library of Congress reading program for people who are blind or have a physical disability. An abridged version is distributed in braille. This periodical lists digital talking books and magazines available through a network of cooperating libraries and carries news of developments and activities in services to people who are blind, visually impaired, or cannot read standard print material because of an organic physical disability. The annotated list in this issue is limited to titles recently added to the national collection, which contains thousands of fiction and nonfiction titles, including bestsellers, classics, biographies, romance novels, mysteries, and how-to guides. Some books in Spanish are also available. To explore the wide range of books in the national collection, visit the NLS Union Catalog online at www.loc.gov/nls or contact your local cooperating library. Talking Book Topics is also available in large print from your local cooperating library and in downloadable audio files on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site at https://nlsbard.loc.gov. An abridged version is available to subscribers of Braille Book Review. Library of Congress, Washington 2017 Catalog Card Number 60-46157 ISSN 0039-9183 About BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download. To use BARD, contact your cooperating library or visit https://nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. -

On Distinguishing Attack Against the Reduced Version of the Cipher Nlsv2

Ø Ñ ÅØÑØÐ ÈÙ ÐØÓÒ× DOI: 10.2478/v10127-012-0037-5 Tatra Mt. Math. Publ. 53 (2012), 21–32 ON DISTINGUISHING ATTACK AGAINST THE REDUCED VERSION OF THE CIPHER NLSV2 Michal Braˇsko — Jaroslav Boor ABSTRACT. The Australian stream cipher NLSv2 [Hawkes, P.—Paddon, M.– –Rose, G. G.—De Vries, M. W.: Primitive specification for NLSv2, Project eSTREAM web page, 2007, 1–25] is a 32-bit word oriented stream cipher that was quite successful in the stream ciphers competition—the project eSTREAM. The cipher achieved Phase 3 and successfully accomplished one of the main require- ments for candidates in Profile 1 (software oriented proposals)—to have a better performance than AES in counter mode. However the cipher was not chosen into the final portfolio [Babbage, S.–De Canni`ere, Ch.–Canteaut, A.–Cid, C.– –Gilbert, H.–Johansson, T.–Parker, M.–Preneel, B.–Rijmen, V.–Robshaw, M.: The eSTREAM Portfolio, Project eSTREAM web page, 2008], because its per- formance was not so perfect when comparing with other finalist. Also there is a security issue with a high correlation in the used S-Box, which some effective distinguishers exploit. In this paper, a practical demonstration of the distinguish- ing attack against the smaller version of the cipher is introduced. In our experi- ments, we have at disposal a machine with four cores (IntelR CoreTM Quad @ 2.66 GHz) and single attack lasts about 6 days. We performed successful practi- cal experiments and our results demonstrate that the distingushing attack against the smaller version is working. 1. Introduction The cipher NLSv2 is a synchronous, word-oriented stream cipher developed by Australian researchers P h i l i p H a w k e s, C a m e r o n M c D o n a l d, M i - chael Paddon,Gregory G.Rose andMiriam Wiggers de Vreis in 2007 [6].