1481009056P5M14TEXT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

University of Alberta Ascending the Canadian Stage: Dance and Cultural Identity in the Indian Diaspora by Meera Varghese A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45746-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45746-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Dance (Code No

DANCE (CODE NO. 056 TO 061) 2020-21 The objective of the theory and practical course in Indian Classical Dance, Indian Traditional Dance, Drama or Theatre forms is to acquaint the students with the literary and historical background of the Indian performing arts in general, arid dance drama form offered in particular. It is presumed that the students offering these subjects will have had preliminary training in the particular form, either within the school system or in informal education. The Central Board of Secondary Education being an All India Organization has its schools all over the country. In order to meet the requirements of the schools, various forms or regional styles have been included in the syllabus. The schools may OFFER ANY ONE OF THE STYLES. Since the syllabi are closely linked with the culture, it is desirable that the teachers also make themselves familiar with the aspects of Indian Cultural History; classical and medieval period of its literature. Any one style from the following may be offered by the students: INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE (a) Kathak (b) Bharatnatyam (c) Kuchipudi (d) Odissi (e) Manipuri (f) Kathakali (A) KATHAK DANCE (CODE NO. 056) CLASS–XII (2020-21) Total Marks: 100 Theory Marks: 30 Time-2 Hours 1. A brief history with other classical dance styles of India. 2. Acquaintance with the life sketch of few great exponents from past and few from present of the dance form. 3. Elementary introduction to the text Natyashastra, Abhinaya Darpan: (a) Identification of the author and (approximate date). (b) Myths regarding the origin of dance according to each text. -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary -

SCW Design Contest to Mark Women's Day DT News Network

Sunday, August 27, 2017 3 Percussion jamboree from October 5 to 6 SCW design contest DT News Network Sreekanth and Mattannur [email protected] Sreeraj. ver 150 Indian Day-two will kick off with percussionists will the performance ‘Kombu performO at a major music and Pattu’ followed by ‘Kuzhal to mark Women’s Day cultural extravaganza to be Pattu’. be held from October 5 and 6 Day-two will also feature at the Indian School Bahrain ‘Erattapanthy Panchaari premises in Isa Town, the Melam’ to be performed by organisers said at a press more than 150 percussionists conference held at Adliya on a special custom-built yesterday. stage arranged at the Indian Sopanam Vadya Kala School ground. Sangham, in association “This event will mesmerize with Choice Advertising the audience with several and Publicity, will be percussion arts of Kerala The meeting organised to announce the design contest at the Bahrain National Museum organising the event entitled in its various forms. ‘Vadyasangaman 2017’. The “Vadyasangamam 2017” DT News Network engineering streams will at engineering colleges in to attend the workshops and event will include a percussion will be steered under the Manama participate in the contest, architecture, civil, mechanical, lectures to be held as part of ensemble involving 150 leadership of legendary he Supreme Council the organisers said during electrical, landscaping and the contest, as well as personal artists. percussionist ‘Padmashri for Women (SCW) is an introductory meeting urban planning. interviews. According to the organisers, Mattannur Sankarankutty organising,T in cooperation held at the Bahrain National Participants, not exceeding The designs should provide such a performance will be Maraar’,” the organizers said. -

June 2017.Pmd

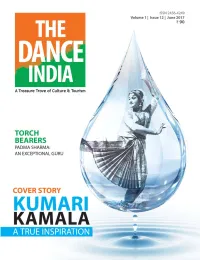

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

Major Points About Kerala - Know Your States in PDF for SSC, Bank Exams

Major Points about Kerala - Know Your States in PDF for SSC, Bank Exams If you look at the question papers of exams like SSC CHSL, SSC CGL, SSC MTS, IBPS PO, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, IPPB Sc. I, LIC AAO, etc. you will find a lot of questions related to India and its states. Questions based on various states of India form a large part of the General Awareness section of many government and bank exams. In fact, if you are thinking of appearing for state govt. exams, it becomes all the more important for you to know your state. Our latest GK Notes series – ‘Know your States’, will help you learn major facts, global importance, and culture of every state. This particular article will help you learn everything about Kerala in one glance. Read the complete article to find out the history, economy, geographical significance, flora & fauna, important sites, tourist attractions, etc. about Kerala. You can also download this article as PDF to keep it handy. 1 | P a g e Kerala is the state in India with the 2nd highest number of literates as well the sex ratio in the state is like an example for the whole country to follow. People of Kerala are very helpful in nature. Kerala is situated within the beauty of nature. From its beaches to coconut trees, its food to its backwaters, you will find a lot in Kerala. You can read the table below to know in detail about the state of Kerala. Important Points about Kerala in PDF Kerala Capital Thiruvananthapuram Formed in 1 November 1956 Districts 14 Language Malayalam Known as/for -Nickname: Spice Garden of India God’s own Country, Land of Backwaters. -

Szcc Annual Report 2016-2017

ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT 2016-2017 The South Zone Cultural Centre at Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu was established as a Society under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, came into existence on 31st January 1986 with the objective to integrate people of India through Culture, art and heritage. The Centre has jurisdiction over the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Union Territories of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep and Puducherry. During the year 2016-17 SZCC, in association with the Member States, has arranged around 169 programmes. More than 10,414 artistes from various parts of the country have been paid for their participation in various programmes conducted during the year. These programmes could be conducted successfully with the active participation and support of each Member State. Some of the programmes organised are highlighted below: ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT AND REVIEW OF THE PROGRAMMES CONDUCTED DURING THE YEAR 2016-2017 During the Year 2016-17 the South Zone Cultural Centre, Thanjavur has conducted 169 Cultural Programmes in which 10414 artistes have participated. The following is a comparative statement of programmes conducted in various States/Union Territories during the last 7 years. Sl. 2010- 2011- 2012- 2013- 2014- 2015- 2016- State/UT No 11 12 13 14 15 2016 2017 01 Andaman &Nicobar Islands 1 1 1 5 2 01 01 02 Andhra Pradesh 1 3 3 7 4 07 07 03 Karnataka 1 4 4 9 20 09 17 04 Kerala 5 3 6 27 25 14 11 05 Lakshadweep 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 06 Puducherry 5 2 7 18 10 21 22 07 Tamil Nadu 26 51 71 70 86 110 92 08 Telangana 0 0 0 0 1 04 05 09 Other Zones 4 0 3 9 10 11 14 10 Programmes Abroad 0 0 0 5 1 0 0 Total 44 65 95 150 160 177 169 Further, the number of artistes from the Member States and also from other States performed in various programmes organised by SZCC during the past 7 years is shown below 175 Artistes from Member States performed during the years from 2010-2011 to 2016-2017 2015-2016 2016-2017 Sl. -

The Humanitarian Initiatives

® THE HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES OF SRI MATA AMRITANANDAMAYI DEVI (MATA AMRITANANDAMAYI MATH) embracing the world ® is a global network of charitable projects conceived by the Mata Amritanandamayi Math (an NGO with Special Consultative Status to the United Nations) www.embracingtheworld.org © 2003 - 2013 Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust, Amritapuri, Kollam, 690525, India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, reproduced, transcribed or translated into any language, in any form, by any means without prior agreement and written permission of the publisher. Edition 12, January 2013 Amma | 06 Disaster Relief | 15 Empowering Women | 34 Building Homes | 38 Community Outreach | 45 Care Homes for Children | 51 Public Health | 56 Education for Everyone | 59 Research for a Better World | 66 Healthcare | 73 Fighting Hunger | 82 Green Initiatives | 85 Amrita Institutions | 88 my religion Contacts | 95 is love Amma The world should know that a life dedicated to selfless love and service is possible. Amma Amma’s Life Amma was born in a remote coastal village in Amma was deeply affected by the profound Each of Embracing the World’s projects has Kerala, South India in 1953. Even as a small suffering she witnessed. According to Hindu- been initiated in response to the needs of girl, she drew attention with the many hours she ism, the suffering of the individual is due to the world’s poor who have come to unburden spent in deep meditation on the seashore. She his or her own karma — the results of actions their hearts to Amma and cry on her shoulder. -

Alankar: First Year Coursepack

LEVEL ONE WORKSHEETS The activities of the worksheet must be completed by the students. They may refer to class notes and online resources. Completed worksheets should be submitted as part of the online theory exam in the last week of February. Unfinished worksheets may be submitted with the theory exam of the following year. 1. Concepts Mangalacharan: This is the very first item a student of Odissi learns. This is an invocatory item in which one pays tribute to Mother Earth, Lord Jagannath and other Gods, also with stanzas to welcome the audience and to thank one's Gurus. "Mangala" means goodness, and "charan" mean wishing. Mangalacharan's rhythmic sequence of steps forming the Bhumi Pranam (salutation to Mother Earth) and Trikhandi Pranam (three-fold salutation to God, the Guru, and the audience) will be completed. Bhumi Pranam: The lesson starts with an brief and respectful apology to the Earth, for we are about to spend the next hour stamping on her. Tribhanga: The dancer's body is divided into three bhangas along which deflections of the head, torso and hips can take place. The technique is built on the principle of an unequal division of weight and the shift of weight from one foot to the other. The movement of the head, the torso, the hips and the knees, are important. Hip deflection is the characteristic feature of this dance style. The tribhanga is one of the most typical poses of Odissi dancing. Chowka: In this stance, weight is equally distributed and altogether four right angles create a perfect geometrical motif.