Chapter 3 China and the World Section 1: China and Asia’S Evolving Security Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissenting Media in Post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip the De

Dissenting media in post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip The de-colonization of Hong Kong took the form of Britain returning the territory to China in 1997 as a Special Administrative Region (SAR). Twenty years after the political handover, the “one country, two systems” arrangement designed by China to govern the Hong Kong SAR is facing serious challenge: Many in Hong Kong have come to regard Beijing as an unwelcome control master; and calls for self-determination have gained a substantial level of popular support. This chapter examines the role of media in this development, as exemplified by key political protest actions. It proposes the notion of “dissenting media” as a framework to integrate relevant academic and journalistic studies about Hong Kong. From the discipline of media and communications study, it suggests that operators of dissenting media are enabled to put forth information and analysis contrary to that of the establishment, which, in turn, help to form an oppositional public sphere. In the process, the identity and communities of dissent are built, maintained, and developed, contributing to the formation of a counter public that participates in oppositional political actions. Studies on the impact of media, mainly conducted in stable Anglo-American societies, tend to consider mainstream media as institutions that index1 or reinforce the status quo,2 and alternative media as forces that challenge established powers.3 In Hong Kong, the 1997 political changeover was accompanied by a reconfiguration of power relationships in line with China’s one-party dictatorship. The change runs counter to the political aspirations of the people of Hong Kong, and has bred a political movement for civil liberties, public accountability, and democracy. -

Public Order Policing in Hong Kong the Mongkok Riot Kam C

PUBLIC ORDER POLICING IN HONG KONG THE MONGKOK RIOT KAM C. WONG Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y. C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, VIC, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Reflecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the field of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 Kam C. Wong Public Order Policing in Hong Kong The Mongkok Riot Kam C. Wong Xavier University (Emeritus) Cincinnati, OH, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-319-98671-5 ISBN 978-3-319-98672-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98672-2 Library of Congress Control -

Academic Freedom and Critical Speech in Hong Kong: China’S Response to Occupy Central and the Future of “One Country, Two Systems”∗

Academic Freedom and Critical Speech in Hong Kong: China’s Response to Occupy Central and the Future of “One Country, Two Systems”∗ Carole J. Petersen† and Alvin Y.H. Cheung†† I.!!!!!!Introduction .............................................................................. 2! II.!!!!The “One Country, Two Systems” Model: Formal Autonomy but with an Executive-Led System ...................... 8! III. Legal Protections for Academic Freedom and Critical Speech in Hong Kong’s Constitutional Framework ............ 13! IV. University Governance: The Impact of Increased Centralization and Control ................................................... 20! V. !Conflicts between The Academic Community and the Hong Kong and Central Governments ................................ 28! VI. Beijing’s Retribution: Increased Interference in Hong Kong Universities ................................................................ 40! VII. The Disapearing Booksellers ............................................... 53! VIII. Conclusion ........................................................................... 58! *Copyright © 2016 Carole J. Petersen and Alvin Y.H. Cheung. The authors thank the academics who agreed to be interviewed for this article and research assistants Jasmine Dave, Jason Jutz, and Jai Keep-Barnes for their assistance with research and editing. This is an updated version of a paper presented at a roundtable organized by the Council on Foreign Relations on December 15, 2015, and the authors thank the chair of the roundtable, Professor Jerome A. Cohen, and other participants for their comments. The William S. Richardson School of Law at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa supported Professor Petersen’s travel to Hong Kong to conduct interviews for this article. † Carole J. Petersen is a Professor at the William S. Richardson School of Law and Director of the Matsunaga Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, University of Hawai’i at Manoa. She taught law at the University of Hong Kong from 1991–2006 and at the City University of Hong Kong from 1989-1991. -

The East China Sea Disputes: History, Status, and Ways Forward

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Almae Matris Studiorum Campus Asian Perspective 38 (2014), 183 –218 The East China Sea Disputes: History, Status, and Ways Forward Mark J. Valencia The dispute over ownership of islands, maritime boundaries, juris - diction, perhaps as much as 100 billion barrels of oil equivalent, and other nonliving and living marine resources in the East China Sea continues to bedevil China-Japan relations. Historical and cultural factors, such as the legacy of World War II and burgeoning nation - alism, are significant factors in the dispute. Indeed, the dispute seems to have become a contest between national identities. The approach to the issue has been a political dance by the two coun - tries: one step forward, two steps back. In this article I explain the East China Sea dispute, explore its effect on China-Japan relations, and suggest ways forward. KEYWORDS : China-Japan relations, terri - torial disputes, nationalism. RELATIONS BETWEEN THE PEOPLE ’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (PRC) AND Japan are perhaps at their lowest ebb since relations were for - mally reestablished in 1972. The d ispute over islets and maritime claims in the East China Sea has triggered m uch of this recent deterioration . Because of the dispute, China has canceled or refused many exchanges and meetings of high-level officials, including summit meetings. In fact, China has said that a summit meeting cannot take place until or unless Japan acknowledges that a dispute over sovereignty and jurisdiction exists, something Japan has thus far refused to do. -

Disputes Over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies Chin-Chung Chao University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected]

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Communication Faculty Publications School of Communication 6-2014 Disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies Chin-Chung Chao University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Dexin Tian Savannah College of Art and Design, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/commfacpub Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Chao, Chin-Chung and Tian, Dexin, "Disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies" (2014). Communication Faculty Publications. 85. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/commfacpub/85 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy June 2014, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 19-47 ISSN: 2333-5866 (Print), 2333-5874 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies Chin-Chung Chao1 and Dexin Tian2 Abstract This study explores the communication tactics and grand strategies of each of the involved parties in the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands disputes. Under the theoretical balance between liberal -

China-Taiwan Relations: the Shadow of SARS

China-Taiwan Relations: The Shadow of SARS by David G. Brown Associate Director, Asian Studies The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies Throughout this quarter, Beijing and Taipei struggled to contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS dramatically reduced cross-Strait travel; its effects on cross-Strait economic ties appear less severe but remain to be fully assessed. SARS intensified the battle over Taiwan’s request for observer status at the World Health Organization (WHO). Although the World Health Assembly (WHA) again rejected Taiwan, the real problems of a global health emergency led to the first contacts between the WHO and Taiwan. Beijing’s handling of SARS embittered the atmosphere of cross- Strait relations and created a political issue in Taiwan that President Chen Shui-bian is moving to exploit in next year’s elections. SARS The SARS health emergency dominated cross-Strait developments during this quarter. With the dramatic removal of its health minister and the mayor of Beijing in mid-April, Beijing was forced to admit that it was confronting a health emergency with serious domestic and international implications. For about a month thereafter, Taiwan was proud of its success in controlling SARS. Then its first SARS death and SARS outbreaks in several hospitals led to first Taipei and then all Taiwan being added to the WHO travel advisory list. The PRC and Taiwan each in its own way mobilized resources and launched mass campaigns to control the spread of SARS. By late June, these efforts had achieved considerable success and the WHO travel advisories for both, as well as for Hong Kong, had been lifted. -

US Ambiguity on the Senkakus' Sovereignty

Naval War College Review Volume 72 Article 8 Number 3 Summer 2019 2019 Origins of a “Ragged Edge”—U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovereignty Robert C. Watts IV Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Watts, Robert C. IV (2019) "Origins of a “Ragged Edge”—U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovereignty," Naval War College Review: Vol. 72 : No. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol72/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Watts: Origins of a “Ragged Edge”—U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovere ORIGINS OF A “RAGGED EDGE” U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovereignty Robert C. Watts IV n May 15, 1972, the United States returned Okinawa and the other islands in the Ryukyu chain to Japan, culminating years of negotiations that some have 1 Ohailed as “an example of diplomacy at its very best�” As a result, Japan regained territories it had lost at the end of World War II, while the United States both retained access to bases on Okinawa and reaffirmed strategic ties with Japan� One detail, however, complicates this win-win assessment� At the same time, Japan also regained administrative control over the Senkaku, or Diaoyu, Islands, a group of uninhabited—and uninhabitable—rocky outcroppings in the East China Sea�2 By 1972, both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan also had claimed these islands�3 Despite passing con- trol of the Senkakus to Japan, the United States expressed no position on any of the competing claims to the islands, including Japan’s� This choice—not to weigh in on the Senkakus’ sovereignty—perpetuated Commander Robert C. -

Denationalizing International Law in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island Dispute

THE PACIFIC WAR, CONTINUED: DENATIONALIZING INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE SENKAKU/DIAOYU ISLAND DISPUTE Joseph Jackson Harris* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 588 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................. 591 A. Each State’s Historical Links to the Islands............................. 591 B. A New Dimension to the Dispute: Economic Opportunities Emerge ..................................................................................... 593 III. INTERNATIONAL LAW GOVERNING THE DISPUTE .......................... 594 A. Territorial Acquisition and International Rules of Sovereignty ............................................................................... 594 B The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and Exclusive Economic Rights ...................................................... 596 IV. COMPETING LEGAL CLAIMS AND THE INTERACTION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, NATIONALIST HISTORY, AND STATE ECONOMIC INTERESTS .................................................................... 596 A. Problems Raised By the Applicable International Law ........... 596 B. The Roots of the Conflict in the Sino-Japanese Wars .............. 597 V. ALTERNATIVE RULES THAT MIGHT PROVIDE MORE STABLE GROUNDS FOR RESOLUTION OF THE DISPUTE ................................ 604 A. Exclusive Economic Zones: Flexibility over Brittleness .......... 608 B. Minimal Contacts Baseline and Binding Arbitration ............... 609 C. The -

Read the Afternoon Keynote Address

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES and THE EPOCH FOUNDATION CROSS-STRAIT ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL RELATIONS AND THE NEXT AMERICAN ADMINISTRATION KEYNOTE ADDRESS H.E. VINCENT SIEW VICE PRESIDENT, REPUBLIC OF CHINA Wednesday, December 3, 2008 Far Eastern Plaza Hotel Taipei, Republic of China (Taiwan) Transcript prepared from an audio recording. ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 Welcome Remarks Paul S.P. Hsu President, Epoch Foundation and Chairman and CEO, PHYCOS International Co. Richard Bush Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies, Brookings Keynote Address: U.S. Foreign Policy in the New Administration Strobe Talbott President, The Brookings Institution Panel I: Asia Policy under the New U.S. Administration A view from the United States Michael Schiffer, Program Officer, Stanley Foundation A view from Hong Kong Frank Ching, Senior Columnist, South China Morning Post; CNAPS Advisory Council Member A view from Japan Tsuyoshi Sunohara, Senior Staff Diplomatic Writer, International News Department, Nikkei Newspaper A view from Korea Wonhyuk Lim, Director, Office for Development Cooperation, Korea Development Institute; CNAPS Visiting Fellow, 2005-2006 A view from Taiwan Erich Shih, News Anchor/Senior Producer, CTi Television, Inc.; Visiting Scholar, Peking University School of International Studies; CNAPS Visiting Fellow, 2003-2004 Afternoon Keynote Address Hon. Vincent Siew, Vice President of the Republic -

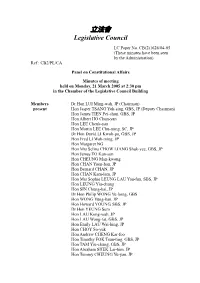

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/CA

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1626/04-05 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/CA Panel on Constitutional Affairs Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 21 March 2005 at 2:30 pm in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP (Chairman) present Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Dr Hon David LI Kwok-po, GBS, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Hon Margaret NG Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, GBS, JP Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Hon Bernard CHAN, JP Hon CHAN Kam-lam, JP Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Hon SIN Chung-kai, JP Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, JP Hon Howard YOUNG, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon CHOY So-yuk Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, JP - 2 - Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon Vincent FANG Kang, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH Hon LEE Wing-tat Hon LI Kwok-ying, MH Dr Hon Joseph LEE Kok-long Hon Daniel LAM Wai-keung, BBS, JP Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, SBS, JP Hon MA Lik, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, SBS, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, -

27 the China Factor in Taiwan

Wu Jieh-min, 2016, “The China Factor in Taiwan: Impact and Response”, pp. 425-445 in Gunter Schubert ed., Handbook of T Modern Taiwan Politics and Society, Routledge. 27 THE CHINA FACTOR IN TAIWAN Impact and response Jieh-Min Wu* Since the turn of the century, the rise of China has inspired global a1nbitions and heightened international anxiety. Though Chinese influence is not a ne\V factor in the international geo political syste1n, the synergy between China's growing purchasing po\ver and its political \vill is dra\ving increasing attention on the world stage. With China's e111ergence as a global econontic powerhouse and the Chinese state's extraction of massive revenues and tremendous foreign reserves, Beijing has learned to flex these financial 1nuscles globally in order to achieve its polit ical goals. Essentially, the rise of China has enabled the PRC to speed up its n1ilitary moderniza tion and adroitly co1nbine econonllc measures and 'united front \Vork' in pursuit of its national interests. Hence Taiwan, whose sovereignty continues to be contested by the PRC, has been heavily i1npacted by China's new strategy. The Chinese ca1npaign kno\vn as 'using business to steer politics' has arguably been success ful in achieving inany of the effects desired by Beijing. For exan1ple, the Chinese government has repeatedly leveraged Taiwan's trade and econonllc dependence to intervene in Taiwan's elections. Such econonllc dependence n1ay constrain Taiwanese choices within a structure of Beijing's creation. In son1e historical 1no1nents, however, subjective identity and collect ive action could still en1erge as 'independent variables' that open up \Vindo\vs of opportun ity, expanding the range of available choices. -

Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 2021 Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism Shucheng Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Shucheng Wang, Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 21 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WANG_2.9.21 2/10/2021 1:03 PM HONG KONG’S CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE UNDER CHINA’S AUTHORITARIANISM Shucheng Wang∗ ABSTRACT Acts of civil disobedience have significantly impacted Hong Kong’s liberal constitutional order, existing as it does under China’s authoritarian governance. Existing theories of civil disobedience have primarily paid attention to the situations of liberal democracies but find it difficult to explain the unique case of the semi-democracy of Hong Kong. Based on a descriptive analysis of the practice of civil disobedience in Hong Kong, taking the Occupy Central Movement (OCM) of 2014 and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement of 2019 as examples, this Article explores the extent to which and how civil disobedience can be justified in Hong Kong’s rule of law- based order under China’s authoritarian system, and further aims to develop a conditional theory of civil disobedience for Hong Kong that goes beyond traditional liberal accounts.