Dual -Enrolled Student Success in an Open Enrollment Community College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profiles : Mid-Coast Working Women

Profiles: Mid-Coast W orking W omen Compiled by Participants and Staff Project Advance Waldoboro, Maine ©1981 Illustrated by Teresa Ginnaty Narda Brown VII. EDUCATIONAL/SOCIAL SERVICES Loraine Crosby — Adult Education Coordinator 85 by Laurie Creamer Jini Powell — Art Teacher by Teresa Ginnaty Anna Rainey — School Librarian by Evelyn Hunt Pam Fogg — Director of Deaf Services by Narda Brown 90 Pat McCallum — Ministry Student by Suzanne Smith 91 Anne O. Mueller — Social Worker researched 93 by Christine Starrett Mary Rae Means — Community Mental Health Consultant 94 by Lori Greenleaf Karin Congleton — Family Planning Coordinator 95 by Raelene McCoy VIII. GOVERNMENT SERVICES Eunice Potter — Postal Carrier by Debbie Carver 97 Holly Dawson — Police Officer by Carol Libby 99 Cynthia D'Ambrosio — Prison Guard by Donna Boynton 101 Mary Genthner — Youth Aide by Laurie Creamer 103 Nancy Pomroy — Selectwoman by Carol Libby 104 Ruth Witham — Tax Collector, Treasurer by Suzanne Smith 105 Martha Tibbetts — Town Clerk, Tax Collector, Treasurer 106 by Virginia Quintal Charlotte Sewall — State Senator by Suzanne Smith 107 Olympia J. Snowe — U.S. Congresswoman researched 109 by Melissa Nygaard Acknowledgments by Janice McGrath HI Contributors 112 ★ * * This publication, undertaken with the goodwill and help of many people, is a sampling of career experiences of area friends, neighbors and acquaintances. Although it could not begin to represent all of the jobs in which Mid-Coast women are engaged, we nevertheless hope it may be of help to others in their search for fulfilling work. INTRODUCTION The image of the American woman was once this: a bonnet-and- apron-tied mistress churning butter while her four sons and two daughters gulp down their midday meal. -

Northern Highlands Regional High School Class of 2011 Profile

Northern Highlands Regional High School Class Of 2011 Profile 298 Hillside Avenue, Allendale, New Jersey 07401 Telephone: 201-327-8700 FAX: 201-236-9543 www.northernhighlands.org ADMINISTRATION John J. Keenan, Superintendent Joseph J. Occhino, Principal Lauren Zirpoli, Assistant Principal Robert E. Williams, Dean of Student Activities ACADEMIC PREPARATION OF FACULTY B.A. 27 M.A. 63 M.A. plus 30 18 M.A. plus 60 23 Ph.D./Psy.D./Ed.D./J.D. 2 THE COMMUNITIES The suburban towns of Allendale, Upper Saddle River, Ho-Ho-Kus and Saddle River are located 20 miles from New York City. Residents are employed primarily in executive, professional, and managerial positions. Northern Highlands is the hub of activity for our students; it serves as both an academic and social community. THE HIGH SCHOOL Northern Highlands Regional High School is a four-year comprehensive public high school that addresses the needs of all of its students and has as its chief emphasis preparation for education beyond high school. Current school population is 1321 with 312 students enrolled in the 12th grade. ACCREDITATION New Jersey State Department of Education GUIDANCE DEPARTMENT: Thomas M. Buono, Supervisor Jennifer Ferentz, Counselor ext. 269 Jennifer Saxton, Counselor ext. 293 Barbara Cucinotta, Adm. Asst. ext. 219 Darcy Hoberman, Counselor ext. 284 Michael Stone, Counselor ext. 288 Ann Karpinecz, Secretary ext. 209 Stephen Jochum, Counselor ext. 291 Denise Talotta, Counselor ext. 296 Josephine Klomburg, Secretary ext. 256 Kerry Miller, Counselor ext. 292 GPA DISTRIBUTION - Northern Highlands does not rank. GPA QUALITY POINTS GPA is cumulative and comprises final grades from all courses, including Physical Education/Health COURSE LEVEL (courses designated Pass/Fail are not included). -

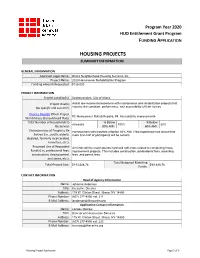

Housing Projects Summary Information

Program Year 2020 HUD Entitlement Grant Program FUNDING APPLICATION HOUSING PROJECTS SUMMARY INFORMATION GENERAL INFORMATION Applicant Legal Name: Project Name: Funding Amount Requested: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Location(s): Project Goal(s) (be specific and succinct): Priority Need(s) Which Project Will Address (Consolidated Plan): Total Number of Households to % Below % Below Be Served: 80% AMI: 60% AMI: Characteristics of People to Be Served (i.e., youth, elderly, disabled, formerly incarcerated, homeless, etc.): Proposed Use of Requested Funds (i.e., professional fees, construction, downpayment assistance, etc.): Total Budgeted Matching Total Project Cost: Funds: CONTACT INFORMATION Head of Agency Information Name: Title: Address: Phone Number: E‐Mail Address: Application Contact Information Name: Title: Address: Phone Number: E‐Mail Address: Housing Project Application Page 1 of 9 PROJECT DESCRIPTION In the space below, provide a clear project summary that includes a description of the proposed project. Include the Census tract number in which the project will be located (see Application Instructions). ~~------------~INSERT EXCEL BUDGET SPREADSHEET(S) IMMEDIATELY AFTER THIS PAGE. Housing Project Application Page 2 of 9 HOUSING PROJECT DEVELOPMENT BUDGET - PERMANENT FINANCING Note: Please complete separate "Developt. Budget - Constr." tab for construction financing, if applicable. SOURCES - PERMANENT FINANCING AMOUNT AMOUNT % OF TOTAL FUNDING SOURCE TITLE SECURED* UNSECURED** BUDGET 1. PY2020 CDBG/HOME $125,000.00 64.62% 2. Ithaca Neighborhood Housing Services, Inc. $62,446.76 32.28% 3. NYSERDA-EmPower & Assisted Home Performance w/ Energy Star $6,000.00 3.10% 4. 0.00% 5. 0.00% 6. 0.00% 7. 0.00% 8. 0.00% TOTAL SECURED & UNSECURED FUNDING $62,446.76 $131,000.00 100.00% TOTAL PROJECT BUDGET $193,446.76 100% LEVERAGE OF SECURED FUNDING PERCENTAGE 32.28% * Supporting documentation is required for amounts listed as secured. -

PMHS Profile

Pelham Memorial High School CEEB/ACT 334470 THE HIGH SCHOOL Pelham Memorial High School (PMHS) is located in the Town of Pelham in southern Westchester County, a half hour north of New York City. Its 12,500 residents range from professionals to skilled workers who all share a commitment to education as well as the arts, athletics and civic responsibility. As a 4-year high school with academically diverse students, PMHS takes pride in its rigorous High School Profile college preparatory program and extensive extracurricular, athletic and fine arts opportunities. 2018 - 2019 Based upon New York State census guidelines, the PMHS population is 68.2% White, 15.2% Pelham Memorial High School Hispanic, 5.2% African-American, 6.2% Asian, and 5.2% Multiracial. 575 Colonial Avenue Pelham, NY 10803 (914) 738-8101 CLASS OF 2018 School Year (914) 738-6706, fax 212 GRADUATES 2 semesters, 4 quarters pmhs.pelhamschools.org School Enrollment Awards 913 students (Grades 9 -12) 6 National Merit Finalist Class of 2019 8 National Merit Commended Students 219 students Dr. Cheryl Champ Accreditation Superintendent Post Secondary Education: 94.3% Middle States Association of Colleges 4-Year Colleges: 90.1% and Schools, New York State Board of Dr. Steven Garcia 2-Year Colleges: 4.2% Regents, and Tri -State Consortium Assistant Superintendent Mrs. Jeannine Clark Principal Programs and Opportunities Our program is robust and diverse to meet the needs and interests of our students: Mr. Judd Rothstein Assistant Principal w Specialized facilities including a Bio-Tech Lab, World Languages Audio and Computer Labs, Fitness Center, Broadcast Media Studio, and MakerSpace Lab w 2017-18 Test Administration Mr. -

Project Advance Biology: an Alternative to Advanced Placement Biology

Project Advance Biology: An Alternative to Advanced Placement Biology SalvatoreTocci Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/44/5/286/39719/4447505.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 FORTHE PAST 25 years,the AdvancedPlacement lege-level courses, identical in all important respects to (AP) Program has given high school students the op- those taught at Syracuse University, are offered in bi- portunity to undertake college-level work while in a ology, calculus, chemistry, English, psychology, religion, secondary environment. More than 1,000 colleges and and sociology. (The Project Advance biology program is universities grant credit and/or advanced placement to offered only in New York and New Jersey.) those who obtain a grade on the AP examination that is Having offered the AP biology course as part of our acceptable to the college. By offering college-level science curriculumfor five years, we examined the Syra- courses in 15 differentsubjects, the AP program has even cuse University program to determine if it provided any enabled some high school seniors to earn enough credits advantages compared to the AP course. Based on the to fulfill their freshman requirements for college. Con - informationwe obtained, we decided to switch to the Pro- sidering the rising cost of college tuition, this acceleration ject Advance biology course and have taught this pro- represents a significant savings, while giving the student gram for the past three years. The purpose of this article time for more advanced work or for taking electives. is to discuss the advantages it offers over the AP program Recently, another program that enables high school to both the teachers and students. -

What's News @ Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC What's News? Newspapers 11-19-1984 What's News @ Rhode Island College Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news Recommended Citation Rhode Island College, "What's News @ Rhode Island College" (1984). What's News?. 279. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news/279 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in What's News? by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's Rhode Island Vol. 5, No . 12 November 19, 1984 @ Colleg • 'Good turnout' for fir st RIC Minori ty Reunion Speaker urges red edication in struggle f or r ights Approximately 60 alumni, their wives , coordinator of minority programs and ser friends and college adminisrators attend vices, Jay Grier , to get the college's minori ed the college's fi.J.;t Minority Alumni Reu ty graduates re -involved in the life of the nion Dinner Nov . 10 at the Faculty Center campus . and heard the keynote speaker outline some Grier and Dr. William H. Lopes of the of the implications and challenges facing College Advancement and Support divi blacks in American higher education . sion , agreed that it was a "good turnout" " The edu cational philosophy and at given that this was the first such reunion titude s of Rhode Island' s educational in and that it took place on a holiday stitutJ0n s with re spect to the black com - weekend . -

School Profile 2019-2020 COMMACK HIGH SCHOOL

COMMACK HIGH SCHOOL An International Baccalaureate School School Profile 2019-2020 COMMACK HIGH SCHOOL MISSION STATEMENT The Mission of Commack High School is the development of the mind, character, and physical well being of our students through the creation of an environment that fosters academic excellence, maturity, and mutual respect. SCHOOL Commack High School is a comprehensive four year high school serving the areas of Commack, Dix Hills, East Northport and Smithtown. A low student/faculty ratio provides a challenging academic environment for all students. According to the “New York State School Report Card” Commack High School is one of the highest performing schools in New York State. Last year’s graduating class consisted of 556 students and the total school population was 2,230. COMMUNITY Commack is a residential community of 39,000 people located approximately 50 miles east of New York City in Suffolk County, Long Island. Suffolk County has a population of 1.5 million and adjacent Nassau County has a total of approximately 1.35 million. There are 90 public and private high schools located in Suffolk County. The Northern State Parkway, the Long Island Expressway, Jericho Turnpike and Commack Road are major arteries leading to Commack. The School District consists of one high school, one middle school, two intermediate schools and four elementary schools, with a total enrollment of 5,982 students. ADMINISTRATION COUNSELING CENTER Nicole Kregler, Director Leslie H. Boritz, Principal Alyson Catinella Courtney Meyer Andrea Allen, -

College Credit Cover:Layout 1 2/4/10 11:18 AM Page 1 C O L L E G E Co Lle Ge Cre Dit C R E

College Credit cover:Layout 1 2/4/10 11:18 AM Page 1 C o l l e g e Co lle ge Cre dit C r e he first-year college writing requirement is a time-honored tradition d for Writing in High School i Tin almost every college and university in the United States. Many t high school students seek to fulfill this requirement before entering f o college through a variety of programs, such as Advanced Placement r The “Taking Care of” Business tests, concurrent enrollment programs, the International Baccalaureate W diploma, and early college high schools. The growth of these programs r i t raises a number of questions, including: i n • Is this kind of outsourcing of instruction to noncollege providers of g educational services something to be resisted or embraced? i • What are the possible benefits and detriments to students, their n parents, their teachers, and the educational institutions? What H i standards should be met with respect to student readiness, teacher g preparation, curricular content, pedagogical strategies, and learning h outcomes? S c • How can we create a seamless K –14 educational system that h effectively teaches writing to students in the transition from o adolescence to adulthood? o l Contributors to this volume—including high school teachers, professors at community colleges and universities, and administrators H at both the secondary and postsecondary levels—explore the complexity a of these issues, offer best practices and pitfalls of such a system, n s e establish benchmarks for success, and lay out possible outcomes for a n new educational landscape. -

Tiffany M. Squires

CURRICULUM VITAE Tiffany M. Squires Assistant Professor of Education Leadership College of Education, The Pennsylvania State University 207B Rackley Building · University Park, PA 16802 · (814) 863-3779 · [email protected] AREAS OF INTEREST Educational leadership practice as it effectively leads to school/systems reform and continual improvement, specifically how leaders cultivate school culture, build trusting relationships, and engage in reflective practice. EDUCATION 2015 Doctor of Philosophy, Instructional Design, Development & Evaluation SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY, Syracuse, New York DISSERTATION— “Leading Curricular Change: The Role of the School Principal in the Implementation of the Common Core State Standards” 2007 Certificate of Advanced Studies, Education Leadership LEMOYNE COLLEGE, Syracuse, New York CERTIFICATION— Administration & Pupil Personnel Services, Permanent Certificate, School District Administrator 2005 Master of Science, Instructional Design, Development & Evaluation SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY, Syracuse, New York 2001 Master of Science, Education CANISIUS COLLEGE, Buffalo, New York CERTIFICATION— NYS Permanent Certification PreK-6 with Early Childhood Annotation 1995 Bachelor of Science, Elementary Education STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COLLEGE, Fredonia, New York ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2017-present Assistant Professor, Department of Education Policy Studies, The Pennsylvania State University 2017-present Assistant Director, Online Programs for Education Leadership, The Pennsylvania State University 2016-2017 Adjunct Professor, Field Placement Supervisor, Grand Canyon University RESEARCH EXPERIENCE 2014-2017 Specialist, Research and Evaluation, Syracuse University Office of Academic Affairs • Planned/developed campus-wide system of assessment w Office of Academic Affairs • Identified areas in need of alignment with Middle States for all academic programs • Collaborated with team to develop rubric for academic programs assessment • Developed protocol for organizing data collected campus-wide Tiffany M. -

The Effect of Participation in Syracuse University Project Advance and Advanced Placement on Persistence and Performance at a Four-Year Private University

Syracuse University SURFACE Instructional Design, Development and Evaluation - Dissertations School of Education 8-2012 The Effect of Participation in Syracuse University Project Advance and Advanced Placement on Persistence and Performance at a Four-Year Private University Kalpana Srinivas Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/idde_etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Srinivas, Kalpana, "The Effect of Participation in Syracuse University Project Advance and Advanced Placement on Persistence and Performance at a Four-Year Private University" (2012). Instructional Design, Development and Evaluation - Dissertations. 57. https://surface.syr.edu/idde_etd/57 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Instructional Design, Development and Evaluation - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Abstract Concurrent enrollment programs (CEPs) are an important source of academic preparation for high school students. Along with Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate, CEPs allow students to challenge themselves in high school and prepare for the rigor of college. Many researchers and practitioners have claimed that, when high school students participate in such programs, they become more successful in college, having better retention rates and better grades. Based upon their knowledge about the many students who have participated in CEPs, Marshal and Andrews (2002) note that “there is scarcity of research on dual credit aka concurrent enrollment programs.” The claims for the effectiveness of CEPs must be substantiated. Syracuse University’s concurrent enrollment program, Project Advance (PA), was implemented in 1972 at the request of six local Syracuse high schools.