The Architecture of Uganda Prior to Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

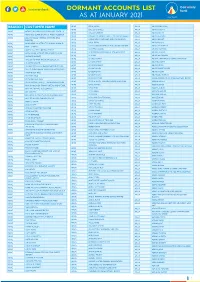

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Uganda Pearl of Africa Uganda Map of Uganda

Destination Showcase: Uganda Pearl of Africa Uganda Map of Uganda H1 Kampala Serena Hotel EUROPE H2 Jinga Nile Resort H3 Sanctuary Gorilla Forest Camp AFRICA SUDAN UGANDA Nile River DEMOCRATIC Moroto REPUBLIC OF CONGO Murchison Falls National Park Lake Albert Masindi Lake Kyoga Mbale Fort Portal H2 H1 Jinja KAMPALA Entebbe Equator Airport Queen Elizabeth National Park Lake Edward Masaka Mbarara Lake Victoria KENYA H3 BWINDI Kabale RWANDA TANZANIA Uganda Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by Tanzania. The southern part of the country includes a substantial portion of Lake Victoria, shared with Kenya and Tanzania. Uganda lies within the Nile basin, and has a varied but generally equatorial climate. Uganda has two official languages: Swahili and The country is fortunate to harbour Lake Victoria, English. Luganda, a southern language, is widely the second largest lake in the world forming the spoken across the country, and multiple other source of the Nile, the second largest river in the languages are also spoken. Uganda’s currency is world. the Ugandan Shilling. Most famous for its gorilla trekking expeditions, Ecologically, Uganda is where the East African friendly Uganda is also home to classic game savannah meets the West African jungle. Where reserves and is rapidly making a name for itself else but in this uniquely lush destination can as an excellent chimpanzee tracking and bird one observe lions prowling the open plains in watching destination. -

Bulange Fire Caused by Petrol

6 NEW VISION, Thursday, November 1, 2012 BUGANDA NEWS Judicial officers Bulange fire Lawyer blasts Police over witchcraft urged to use IT PICTURE BY ALI MAMBULE By ALI MAMBULE Judicial officers, planners and statisticians working caused by Kampala-based state in the justice systems prosecutor Susan Okalany have been urged has attacked the Police over to use Information what she called promoting Communication witchcraft by protecting Technology (ICT) in gender petrol – report traditional herbalists, some reporting so as to dispense of whom engage in human justice faster for the victims By JEFFA LULE AND doors and hurling insults at sacrifice. of sexual violence. The call INNOCENT ANGUYO the guards. Okalany said the Police, was made by Valentine “The head of KPU Capt. especially in the central Namakula, the director of The fire that gutted a security Steven Mivule Kisitu region, were promoting Centre for Justice Studies house at Bulange-Mengo (deceased) sent Pte. Vincent witchcraft by providing and Innovations, during claiming four lives and Katende to check on her. security to the traditionalists a training on gender injuring three others was As he opened the door, fire pretending to be healing reporting at Imperial caused by petrol, according broke out, killing the woman those attacked by demons. Resort Beach Hotel last to the Government analytical instantly while Katende took “I have seen this so many week. She said the use of laboratory report. off with severe injuries,” the times and I confirm that ICT in data entry would Bulange is the administrative report notes. our country needs a lot enable judicial officers to seat for Buganda Kingdom Nabakooba said by the time of prayers to stop such know how long a case has located in Mengo, a Kampala the Police arrived, the body of practices,” Okalany said. -

Water Safety Plans for Utilities in Developing Countries - a Case Study from Kampala, Uganda

Water Safety Plans for Utilities in Developing Countries - A case study from Kampala, Uganda Sam Godfrey, Charles Niwagaba, Guy Howard, Sarah Tibatemwa 1 Acknowledgements The editor would like to thank the following for their valuable contribution to this publication: Frank Kizito, Geographical Information Section (GIS), ONDEO Services, Kampala, Uganda Christopher Kanyesigye, Quality Control Manager National Water and Sewerage (NWSC), Kampala, Uganda Alex Gisagara, Planning and Capital Development Manager, National Water and Sewerage (NWSC), Kampala, Uganda Godfrey Arwata, Analyst Microbiology National Water and Sewerage (NWSC), Kampala, Uganda Maimuna Nalubega, Public Health and Environmental Engineering Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Rukia Haruna, Public Health and Environmental Engineering Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Steve Pedley, Robens Centre for Public and Environmental Health, University of Surrey, UK Kali Johal, Robens Centre for Public and Environmental Health, University of Surrey, UK Roger Few, Faculty of the Built Environment, South Bank University, London, UK The photograph on the front cover shows a water supply main crossing a low lying hazardous area in Kampala, Uganda (Source: Sam Godfrey) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS: WATER SAFETY PLANS FOR UTILITIES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES.1 - A CASE STUDY FROM KAMPALA, UGANDA..................................................1 Acknowledgements.................................................................................................2 -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Planned Shutdown Web October 2020.Indd

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR SEPTEMBER 2020 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED Kampala West Saturday 3rd October 2020 Mutundwe Kampala South 1 33kV Replacement of rotten vertical section at SAFARI gardens Najja Najja Non and completion of flying angle at MUKUTANO mutundwe. North Eastern Saturday 3rd October 2020 Tororo Main Mbale 1 33kV Create Two Tee-offs at Namicero Village MBALE Bubulo T/C, Bududa Tc Bulukyeke, Naisu, Bukigayi, Kufu, Bugobero, Bupoto Namisindwa, Magale, Namutembi Kampala West Sunday 4th October 2020 Kampala North 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX2 Routine Maintenance of 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX 2 Wandegeya Hilton Hotel, Nsooda Atc Mast, Kawempe Hariss International, Kawempe Town, Spencon,Kyadondo, Tula Rd, Ngondwe Feeds, Jinja Kawempe, Maganjo, Kagoma, Kidokolo, Kawempe Mbogo, Kalerwe, Elisa Zone, Kanyanya, Bahai, Kitala Taso, Kilokole, Namere, Lusanjja, Kitezi, Katalemwa Estates, Komamboga, Mambule Rd, Bwaise Tc, Kazo, Nabweru Rd, Lugoba Kazinga, Mawanda Rd, East Nsooba, Kyebando, Tilupati Industrial Park, Mulago Hill, Turfnel Drive, Tagole Cresent, Kamwokya, Kubiri Gayaza Rd, Katanga, Wandegeya Byashara Street, Wandegaya Tc, Bombo Rd, Makerere University, Veterans Mkt, Mulago Hospital, Makerere Kavule, Makerere Kikumikikumi, Makerere Kikoni, Mulago, Nalweuba Zone Kampala East Sunday 4th October 2020 Jinja Industrial Walukuba 11kV Feeder Jinja Industrial 11kV feeders upgrade JINJA Walukuba Village Area, Masese, National Water Kampala East -

(Acacia): the Case of Uganda

FINAL REPORT INFORMATION & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES FOR DEVELOPMENT (ACACIA): THE CASE OF UGANDA DATE: JANUARY 2003 PREPARED FOR: THE IDRC EVALUATION UNIT AUTHOR: DR ZM OFIR, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, EVALNET, PO BOX 41829, CRAIGHALL 2024, SOUTH AFRICA (F) CONTRACT NUMBER: 10714 PROJECTS INCLUDED: The Acacia National Secretariat for Uganda (Project number 055475) The Development of an Integrated Information and Communication Policy for Uganda (Project number 100572) Policy and Strategies for Rural Communications Development in Uganda (Project number 100577) The Development of Operational Guidelines for the Uganda Rural Communications Development Fund (Project number 101134) CONTENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................................4 GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................7 PREAMBLE: Some Key Events that shaped the Development of ICTs in Uganda ......................................................................8 Chapter I APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY...........................................................................................................................11 I.1 Introduction: The Study............................................................................................................ 11 I.2 The Consultant ......................................................................................................................... -

World Bank Document

E1505 Public Disclosure Authorized KAMPALA CITY COUNCIL KKaammppaalllaaIIInnssstttiiitttuutttiiioonnaalllaannddIIInnfffrrraassstttrrruucctttuurrreeDDeevveelllooppmmeenntttPPrrroojjjeeccttt EENNVVIIIRROONNMMEENNTTTAALLLAANNAALLLYYSSIIISS Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report Prepared by: AAqquuaaCCoonnsssuulllttt In association with EMA CONSULT LTD and SAVIMAXX LTD November 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized EA for the Kampala Institutional and Infrastructure Development Project (KIIDP) Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ i LIST OF ACRONYMS..................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT.................................................................................................................. x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... xi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background of the Project............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Terms of Reference.......................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Description of the Project.............................................................................................................. -

Planned Shutdown March 2021

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR MARCH 2021 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED North Eastern Wednesday 03rd March 2021 UETCL Hoima Kinubi 33kV Creating h-p tee-off to install dropout fused isolator for direct Hoima Kibati TC, Kalyabuhire kibati t-off and line clearance Kampala West Wednesday 03rd March 2021 Kisugu 11kV and 33kV switchgear Routine Maintenance Kabalagala Kitaranga,Kiwafu,Meya Beach,Kemifa,Nabutiti,Wheeling Zone,Prayer Palace,Wonder world,Comrade bar,Galax FM,Seroma,Mutesasira zone,Internal East Africa University,Shell Kansanga,Elite supermarket,Saida Bumba, Olanya,Kadaga,Diplomatic hotel,Paradiso hotel,Internatiol Hospital Kampala,Kisugu church of Uganda,Zimwe road,Mukwano Apartment,Kabalagala Police station,Diposh bar,Kironde road,General Machinery,Bukasa, parts of Namuwongo, Seebo Green, Bukasa stone quarry,Musisi road,Water tank Hill,Muyenga Umeme mast,Benging Clinic,Muyenga High school, Muyenga chicken tonigt.Heritage International school, Kisugu ,Kibuli,Kikubamutwe,Kibuli mosque,CID Headquarters,Part of Police barracks,Namuwongo publication,Multiple Industry,Sure telecom switching station,Kakungulu Memorial,Kibuli sec sch,Green Hill Academy Kampala West Wednesday 03rd March 2021 Kisugu 11kV and 33kV Take-off MV Cable Inspection,Replacement of rotten structures & jumper Kabalagala Kitaranga,Kiwafu,Meya Beach,Kemifa,Nabutiti,Wheeling Zone,Prayer Palace,Wonder Structures, Lugogo repairs world,Comrade bar,Galax FM,Seroma,Mutesasira -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.B / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

Preparatory Survey for the Project for Improvement of Traffic Control in Kampala City

KAMPALA CAPITAL CITY AUTHORITY (KCCA) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA PREPARATORY SURVEY FOR THE PROJECT FOR IMPROVEMENT OF TRAFFIC CONTROL IN KAMPALA CITY FINAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. EI EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. JR 19-026 KAMPALA CAPITAL CITY AUTHORITY (KCCA) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA PREPARATORY SURVEY FOR THE PROJECT FOR IMPROVEMENT OF TRAFFIC CONTROL IN KAMPALA CITY FINAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. PREFACE The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) made the decision to conduct a preparatory survey related The Project for Improvement of Traffic Control in Kampala City, the Republic of Uganda. This survey was entrusted to Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd and Eight-Japan Engineering Consultants Inc. The study team held discussions with the government of Uganda and Kampala Capital City Authority officials from June 1 to July 7, 2017 and conducted field surveys in the planned area. This report was completed upon returning and finishing work domestically. JICA hopes that this report will further this project and will be useful for further developing friendship and goodwill between the two countries. Finally, JICA would like to express our sincere gratitude to everyone involved for their cooperation and support regarding the survey. May 2018 Itsu Adachi Director General of Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) SUMMARY 1. Overview of Kampala City The railway network in Uganda is not functioning, so 92% or more of freight and passenger transportation is carried over roads. These roads are critical in terms of Uganda’s economic development. -

Uganda Briefing Packet

UGANDA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET UGANDA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org UGANDA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 5 STATISTICS 10 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 11 HISTORY OVERVIEW 11 Geography 14 Climate and Weather 15 Demographics 16 Economy 17 Education 18 Religion 18 Modern life 19 Poverty 20 NATIONAL FLAG 21 Etiquette 21 CULTURE 24 Orientation 24 Food and Economy 25 Social Stratification 26 Gender Roles and Statuses 26 Marriage, Family, and Kinship 27 Socialization 27 Etiquette 28 Religion 28 Medicine and Health Care 29 Secular Celebrations 29 USEFUL kiswalhili PHRASES 29 SAFETY 32 GOVERNMENT 34 Currency 35 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 28 April, 2016 36 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 36 TIME IN UGANDA 37 EMBASSY INFORMATION 37 Embassy of the United States of America 37 Embassy of Uganda in the United States 37 WEBSITES 38 "2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org UGANDA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the UGANDA Medical and Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families.