On the Elementals and Their Qualities in David Foster Wallaceâ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirited Away Picture Book Free Ebook

FREESPIRITED AWAY PICTURE BOOK EBOOK Hayao Miyazaki | 170 pages | 01 Sep 2008 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781569317969 | English | San Francisco, United States VIZ | See Spirited Away Picture Book Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. This illustrated book tells the story of the animated feature film Spirited Away. Driving to their new home, Mom, Dad, and their daughter Chihiro take a wrong turn. In a strange abandoned amusement park, while Chihiro wanders away, her parents Spirited Away Picture Book into pigs. She must then find her way in a world inhabited by ghosts, demons, and strange gods. Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spirited Away Spirited Away Picture Book Bookplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Spirited Away Picture Book. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. Sort order. Start your review of Spirited Away Picture Book. I bought this picture book a long time ago. I was looking for some in depth books or manga on my favorite movie of all time, Spirited Away by Hayao Miyazaki. I will be adding several gifs of the movie toward the end but they are in no kind of order. -

(RECENT) EPISTEMOLOGY Christian Beyer Edmund Husserl's

CHAPTER ONE HUSSERL’S TRANSCENDENTAL PHENOMENOLOGY CONSIDERED IN THE LIGHT OF (RECENT) EPISTEMOLOGY Christian Beyer Edmund Husserl’s transcendental phenomenology represents an epis- temological project which he sometimes refers to as “First Philosophy”. He also speaks of “Cartesian Meditations” and stresses that “the first philosophical act” is “the universal overthrow of all prior beliefs, however acquired” (Hua VIII, 23).1 This project aims at nothing less than a philo- sophical understanding of our whole view of the world and ourselves. I propose to investigate into this undertaking regarding both its method and content and to relate it, where useful, to more recent (analytic) epistemology. For Husserl, the task of First Philosophy is to philosophically explicate our access to, or being in, the world, i.e., the intentionality of our con- sciousness. By an intentional state of consciousness, an intentional (lived) experience, he understands a state of consciousness that has a subject matter which it is directed toward, so to speak (cp. the literal meaning of the Latin verb intendere); a state that is “as of ” something, represents something. It was Husserl’s teacher Franz Brentano who brought this notion to the attention of philosophers and psychologists. In his Psychol- ogy from an Empirical Standpoint he says: Every mental phenomenon is characterized by what the Scholastics of the Middle Ages called the intentional (or mental) inexistence of an object, and what we might call, though not wholly unambiguously, reference to a content, direction toward an object (which is not to be understood here as meaning a real thing [eine Realität]), or immanent objectivity. -

Phenomenological Research Methods: Extensions of Husserl and Heidegger

o cho l and f S C o o l g a n n i r t i u v e o J P International Journal of School and l s a y n ISSN: 2469-9837 c o h i t o a l o n r g e y t I n Cognitive Psychology Commentary Phenomenological Research Methods: Extensions of Husserl and Heidegger Effie Heotis* College of Arts and Sciences, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, USA ABSTRACT The relevance to understanding the lived experience and consciousness is the focus of a movement that began in the early part of the 20th Century. Phenomenology is a movement that explores the lived experience of a given phenomenon. Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger were two of the most prominent philosophers who spearheaded this movement and subsequently, they developed their own distinct philosophical approaches and methods of inquiry as means to exploring and understanding the human experience. Various and more distinctive psychological research approaches emerged in other disciplines from the philosophies of Husserl and Heidegger, and the researchers who developed these methods contribute to expanding repertoires aimed at understanding of the human experience. Keywords: Phenomenology; Phenomenological research methods; The lived experience; Husserl; Heidegger INTRODUCTION which are uniquely yet collectively designed to shed light on the human experience. Phenomenological research methods are grounded in the rich traditions of phenomenology and hermeneutics and especially Descriptive or Interpretive? the philosophical views of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Central to Husserl’s claim is that the essence of a Descriptive oriented phenomenological research methods phenomenon could be understood through an investigation and maintain that capturing a vivid and precise description description concerning core components of one’s experience concerning the perception of the lived experience can lead to while suspending suppositions [1,2]. -

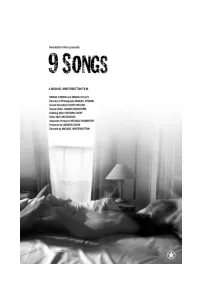

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

Husserl and Merleau-Ponty: a Feminist Critique of the Phenomenological Body

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations Student Research Spring 2021 Husserl and Merleau-Ponty: A Feminist Critique of the Phenomenological Body Jasmin M. Makhlouf The British University in Egypt, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation APA Citation Makhlouf, J. M. (2021).Husserl and Merleau-Ponty: A Feminist Critique of the Phenomenological Body [Master's Thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1617 MLA Citation Makhlouf, Jasmin M.. Husserl and Merleau-Ponty: A Feminist Critique of the Phenomenological Body. 2021. American University in Cairo, Master's Thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1617 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Husserl and Merleau-Ponty: A Feminist Critique of the Phenomenological Body A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Philosophy In Partial Fulfilment to the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Jasmin Mohyeldin Makhlouf Under the supervision of Prof. Steffen Stelzer Spring 2021 Acknowledgments I wish to express my gratitude to Prof. Steffen Stelzer for his kindness, guidance, and encouragement to always examine the big phenomenological questions first. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

HUSSERVS CRISIS of WESTERN SCIENCE Editor's Preface This

Appendix I ALFRED SCHUTZ HUSSERVS CRISIS OF WESTERN SCIENCE Edited by FRED KERSTEN Editor's Preface This letter of Alfred Schutz to Erlc Voegelin was written between 11 November and 13 December, 1943. It contains an extensive reply to a sweeping critique of Husserl's Die Krisis der europl1ischen WlSsenschaften und die transzend entale Phllnomenologie1 which his friend Erlc Voegelin had developed in a letter to him. Voegelin had found merit in some of Husserl's lines of thought but on the whole rejected them as much in their references to historlcal trends in European philosophy, which he showed to be arbitrarily selective and hence at variance with historio graphical facts and objectivity, as in their philosophical inferlority because they were merely epistemological under takings and as such did not reach the level of genuine philosophizing (i.e., they did not constitute a metaphysics). Schutz's defense of Husserl followed two lines of thought: First, that Voegelin misunderstood the whole philosophical intent of Husserl when he considered his interest in past philosophers as serving historiographical interests instead of interest in the problems they had posed; and, second, even if the whole philosophy of Husserl could be subsumed under the heading of epistemology, it would still maintain its high philosophical respectability. At the very end of the letter Schutz spoke of the possibility of continuing this defense of Husserl's way of philosophizing in a further letter. However, no evidence has surfaced to indicate that he found the time to continue his attempt at vindicating Husserl's philosophical dignity. 1 Edmund Husserl, Philosophia, 1936. -

Relationship Between Foreign Film Exposure And

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FOREIGN FILM EXPOSURE AND ETHNOCENTRISM LINGLI YING Bachelor of Arts in English Literature Zhejiang University, China July, 2003 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirement for the degree MASTER OF APPLIED COMMUNICATION THEORY AND METHODOLOGY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY MAY, 2009 1 THESIS APPROVAL SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION This thesis has been approved for the School of Communication And the College of Graduates Studies by: Kimberly A. Neuendorf Thesis Committee Chairman School of Communication 5/13/09 (Date) Evan Lieberman Committee Member School of Communication 5/13/09 (Date) George B. Ray Committee Member School of Communication 5/13/09 (Date) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my special thanks to my advisor, Dr. Kimberly Neuendorf, who provided me with detailed and insightful feedback for every draft, who spent an enormous amount of time reading and editing my thesis, and more importantly, who set an example for me to be a rigorous scholar. I also want to thank her for her encouragement and assistance throughout the entire graduate program. I would also like to thank Dr. Evan Lieberman for his assistance and suggestions in helping me to better understand the world cinema and the cinema culture. Also, I want to thank him for his great encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. I want to offer a tremendous thank you to Dr. Gorge Ray. I learned so much about American people and culture from him and also in his class. I will remember his patience and assistance in helping me finish this program. I am also grateful for all the support I received from my friends and my officemates. -

Leo Strauss and the Problem of Sein: the Search for a "Universal Structure Common to All Historical Worlds"

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2010 Leo Strauss and the Problem of Sein: The Search for a "Universal Structure Common to All Historical Worlds" Jennifer Renee Stanford Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Stanford, Jennifer Renee, "Leo Strauss and the Problem of Sein: The Search for a "Universal Structure Common to All Historical Worlds"" (2010). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 91. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.91 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Leo Strauss and the Problem of Sein : The Search for a “Universal Structure Common to All Historical Worlds” by Jennifer R. Stanford A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: David A. Johnson, Chair Richard H. Beyler Douglas Morgan Michael Reardon Portland State University © 2010 ABSTRACT Leo Strauss resurrected a life-approach of the ancient Greeks and reformulated it as an alternative to the existentialism of his age that grew out of a radicalized historicism. He attempted to resuscitate the tenability of a universal grounded in nature (nature understood in a comprehensive experiential sense not delimited to the physical, sensibly- perceived world alone) that was historically malleable. Through reengagement with Plato and Socrates and by addressing the basic premises built into the thought of Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, Strauss resurrected poetry (art, or the mythos) that Enlightenment thinkers had discarded, and displayed its reasonableness on a par with the modern scientific approach as an animating informer of life. -

River of Fire: Critiquing the Ideology of History (Student Paper)

River of Fire: Critiquing the Ideology of History (Student Paper) I T between the personal and the historical has always been a key theme attracting poets. However, Qurratulain Hyder, in her “historical novel” River of Fire, takes up this relatively common theme in such a way that her treatment of it produces a strong critique of the received notion of history. In other words, the author of River of Fire depicts the, at once, tragic and comic drama which takes place between the historical and the personal. Hyder’s artistic representation of that drama epistemologically questions what is known as history. This paper seeks to explore the ways in which this novel works against, parallel to and as a supplement to history. I use the term “history” here with two distinct meanings. Sudipta Kaviraj defines history as firstly meaning “the course of happenings in time, the seamless web of experiences of a people,” and secondly as meaning “the stories in which what had happened are recov- ered and explained.”1 In this discussion I will read River of Fire against both of these definitions. However, for greater clarity, I will use the term “history” to convey the first meaning and “historiography” to convey the second. II In the world of this novel, princes leave their thrones and their beautiful 1Sudipta Kaviraj, The Unhappy Consciousness (Delhi: Oxford University Pr., ), p. • T A U S women, preferring intellectual pursuits over ruling countries and waging wars. Despite dwelling under trees and only eating meager foods, students live happy lives reflecting on the cosmos and ultimate truths. -

Mo Yan's Reception in China and a Reflection on the Postcolonial Discourse

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 20 (2018) Issue 7 Article 5 Mo Yan’s Reception in China and a Reflection on the ostcolonialP Discourse Binghui Song Shanghai International Studies University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Song, Binghui. -

Simone De Beauvoir's Phenomenology of Sexual Difference

6LPRQHGH%HDXYRLULV3KHQRPHQRORJ\RI6H[XDO'LIIHUHQFH 6DUD+HLQDPDD Hypatia, Volume 14, Number 4, Fall 1999, pp. 114-132 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\,QGLDQD8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/hyp.2005.0029 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/hyp/summary/v014/14.4heinamaa.html Access provided by Osaka University (3 Nov 2014 21:38 GMT) 114 Hypatia Simone de Beauvoir’s Phenomenology of Sexual Difference SARA HEINÄMAA The paper argues that the philosophical starting point of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex is the phenomenological understanding of the living body, developed by Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. It shows that Beauvoir’s notion of philosophy stems from the phenomenological interpretation of Cartesianism which emphasizes the role of evidence, self-criticism, and dialogue. Simone de Beauvoir is not usually considered a philosopher, and her works, including The Ethics of Ambiguity (Pour une morale de l’ambiguïté 1947) and The Second Sex (Le Deuxième sexe 1949), are not usually studied as philosophical.1 Beauvoir is read as a novelist and essayist, and her nonfictional works are taken as sociohistorical studies—popular rather than scholarly, moral rather than ethical. This common view is fundamentally mistaken. I show that Simone de Beauvoir is a philosopher and that she herself considered her work to be phi- losophical. Her understanding of philosophy, however, was specific, and this specificity is the theme of my paper. My claim is that the philosophical context in which Beauvoir operated is the phenomenology of body that Edmund Husserl initiated and Maurice Merleau-Ponty further developed. So I argue against the traditional under- standing according to which Beauvoir’s philosophical notions stemmed from Jean-Paul Sartre’s works; but I also question the more recent argument that Beauvoir based her views on Martin Heidegger’s work.