Honors Thesis (660.5Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instructional Work in Textile Craft ISBN 978-91-7447-435-0

STUDIES IN EDUCATION IN ARTS AND PROFESSIONS 3 Instructional work in textile craft ISBN 978-91-7447-435-0 Instructional work in textile craft Studies of interaction, embodiment and the making of objects Anna Ekström ©Anna Ekström, Stockholm 2012 ISBN 978-91-7447-435-0 Printed in Sweden by US-AB, Stockholm 2012 Distributor: Department of Education in Arts and Professions, Stockholm University THE WORK REPORTED HERE HAS BEEN FUNDED BY THE SWEDISH RESEARCH COUNCIL. Abstract Title: Instructional work in textile craft Language: English Keywords: craft, education, instruction, interaction, ethnomethodology, Sloyd, teacher education ISBN: 978-91-7447-435-0 The focus for this thesis is instructions and their role in guiding students’ activities and understandings in the context of textile craft. The empirical material consists of video recordings of courses in textile craft offered as part of teacher education programs. In four empirical studies, instructions directed towards competences in craft are investigated with the ambition to provide praxeological accounts of learning and instruction in domains where bodily dimensions and manual actions are prominent. The studies take an ethnomethodological approach to the study of learning and instruction. In the studies, instructions related to different stages of the making of craft objects are analysed. Study I highlights instructional work related to objects- yet-to-be and the distinction between listening to instructions as part of a lecture and listening to instructions when trying to use them for the purpose of making an object is discussed. Study II and III explore instructions in relation to developing-objects and examine instructions as a collaboration of hands and the intercorporeal dimensions of teaching and learning craft are scrutinised. -

Sloyd – Tradition in Transition

idskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning Journal of Research in Teacher Education nr 2–3 2006 Theme: Sloyd – Tradition in transition Special issue editors: Kajsa Borg & Per-Olof Erixon Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning Nr 2–3/2006 Årgång 13 FAKULTETSNÄMNDEN FÖR LÄRARUTBILDNING THE FACULTY BOard FOR TeacHer EducatiON Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning nr 2–3 2006 årgång 13 Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning (fd Lärarutbildning och forskning i Umeå) ges ut av Fakultetsnämnden för lärarutbildning vid Umeå universitet. Syftet med tidskriften är att skapa ett forum för lärarutbildare och andra didaktiskt intresserade, att ge information och bidra till debatt om frågor som gäller lärarutbildning och forskning. I detta avseende är tidskriften att betrakta som en direkt fortsättning på tidskriften Lärarutbildning och forskning i Umeå. Tidskriften välkomnar även manuskript från personer utanför Umeå universitet. Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning beräknas utkomma med fyra nummer per år. Ansvarig utgivare: Dekanus Björn Åstrand Redaktör: Fil.dr Gun-Marie Frånberg, 090/786 62 05, e-post: [email protected] Bildredaktör: Doktorand Eva Skåreus e-post: [email protected] Redaktionskommitté: Docent Håkan Andersson, Pedagogiska institutionen Professor Åsa Bergenheim, Institutionen för historiska studier Professor Per-Olof Erixon, Institutionen för estetiska ämnen Professor Johan Lithner, Matematiska institutionen Doktorand Eva Skåreus, Institutionen för estetiska ämnen Universitetsadjunkt Ingela -

Suggested Courses for Handicraft) an Area of Industrial Arts, for Schools in Thailand

SUGGESTED COURSES FOR HANDICRAFT) AN AREA OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS, FOR SCHOOLS IN THAILAND SUGGESTED COURSES FOR HANDICRAFT~ AN AREA OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS, FOR SCHOOLS IN THAILAND by TongpoonRuamsap II Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University of Agriculture and Applied Science 1959 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University of Agriculture and Applied Science;· in partial fulfillment of the requirements for-the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 1960 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 2 1960 SUGGESTED COURSES FOR HANDICRAFT, AN AREA OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS , FOR SCHOOLS IN THAILAND TONGPOON RUAMSAP Master of Science 1960 THESIS APPROVED: Thesis Advisor, Associate Professor and Head, Department of Industrial Arts Education Dean of the Graduate School 452833 ii ACKNOWLEDG:MENT The author wishes to express his appreciation and grati tude to the following people who helped make this study possible. First to his advisor, Professor Cary L. Hill, Head, School of Industrial Arts Education, Oklahoma State University, for his kind and patient advice and assistance. Second, to Professor Mrs. Myrtle c. Schwarz for her kind assistance and encouragement. Third, to the State Superintendents of Public Instruction of the following states: Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Ohio, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Appreciation is extended t·o Professor John B. Tate and Professor L. H. Bengtson,·who gave kind instructions to the author throughout his study at Oklahoma State University. Tongpoon Ruamsap August, 1959 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I., INTRODUCTION •••••_•&ct•o•••••e•• 1 Part A.. The General Scope of the Study. .. • • 3 The Origin of_th~ Study ........... .. " 3 Needs for the Study ......... -

Craftmaking Designers Creativity and Empowerment Through Craft Workshops

Craftmaking Designers Creativity and Empowerment Through Craft Workshops Pro Gradu Tanja Severikangas Faculty of Arts, Industrial Design University of Lapland Fall 2013 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1.1. Community Craftmaking as a Source for Designers(Tokuji Workshops) 1.2. Craftmaker or Designer 1.!. Action #esearch in a Workshop 1.$. Themes 1.%. #esearch Data and Ana&ysis 1.'. (ow the #esearch is Conducted and the *+pected #esult 1.,. The Structure of this Work 2 #esearch Approaches 2.1. Application of the #esearch Approaches 2.2. Action #esearch 2.!. -ractice.&ed #esearch Dia&ogue 2.$. Discourse Ana&ysis ! #esearch -rocess !.1. -reparation of Workshops !.2. Workshops !.!. The #esults of Workshops $ #e&ated Themes $.1. Community Art $.2. Communa& Craftmaking $.!. Workshop $.$. The -rocess of Craftmaking $.%. Meaning of Making Crafts $.'. Creativity $.,. *mpowerment % Conc&usions %.1. Creativity in Craftmaking %.2. Community of *mpo)erment %.!. Iterative Identity 1uilding %.$. A Crafty Designer %.%. The -roject in #etrospective 3 1.Introduction This #ork is constructed so that this chapter, Introduction, includes the frame of reference of the study% The starting point to my researc" #as the relationship &et#een design and craft making as #ell as the inspirational power found in communal craft making. From there I moved on to forming an action researc" project #hic" involved a series of craft #orkshops% 1.1 Community Craftmaking as a Source for Designers (Tokuji Workshops During my exchange at 2amaguchi -refectural University4 I got invol0ed in a project created 5etween the 2amaguchi -refectural University and Tokuji, a smal& town near5y 2amaguchi city. The town faces the same pro5&ems that many smal& towns near 5igger cities6 the population is aging, 5usinesses are going down4 and al& cu&tural activities cease to exist. -

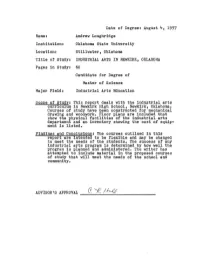

Advisor's Approval ~---~--~~

Date of Degree: August 4, 1957 Name: Andrew Loughridge Institution: Oklahoma State University Location: Stillwater, Oklahoma Title ot Study: INDUSTRIAL ARTS IN NEWKIRK, OKLAHOMA Pages in Study: 60 Candidate for Degree of Master of Science Major Field: Industrial Arts Education Scope of Study: This report deals with the industrial arts curriculum in Newkirk High School, Newkirk, Oklahoma. Courses ot study have been constructed for mechanical drawing and woodwork. Floor plans are included that show the physical facilities of the industrial arts department and an inventory showing the cost of equip ment is listed. Findings and Conclusions: The courses outlined in this report are intended to be flexible and may be changed to meet the needs of the students. The success ot any industrial arts program is determined by how well the program is planned and administered. The writer has attempted to include material in the proposed courses of study that will meet the needs of the school and community. ADVISOR'S APPROVAL ~--------~--~~------------- INDUSTRIAL ARTS IN NEWKIRK, OKLAHOMA INDUSTRIAL ARTS IN NEWKIRK, OKLAHOMA by ANDREW ;ouGHRIDGE Bachelor of Science Southeastern State College Durant, Oklahoma 1953 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University of Agriculture and Applied Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August, 1957 ' !. SEP 16 IS 57 i ;' INDus'l'riIAL ARTS IN NEWKIBK, OKLAHOMA ANDREW LOUGHRIDGE MASTER OF SCIENCE REPORT APPROVED: Adviser and Acting Head School of Industrial Arts Education Associate rof ssor School or ~ ~rial Arts Education Dean of the Graduate School 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer of this report wishes to express his appreciation to Cary L. -

Industrial Education in Puerto Rico

INDUSTRIAL EDUCATION IN PUERTO RICO An Evaluation of the Program in "operation Bootstrap" from 19^8 to 1958 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By JOHN RICHARD McELHENY, B.S., M.S. The Ohio state University I960 Approved by Adviser Department of Education “We, the people of Puerto Rico, in order to organize ourselves politically on a fully democratic basis, to promote the general wel fare, and to secure for ourselves and our posterity the complete enjoyment of human rights, placing our trust in Almighty God, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the Commonwealth which, in the exercise of our natural rights, we now create within our union with the United States of America. “We consider as determining factors in our life our citizenship of the United States of America and our aspiration continually to enrich our democratic heritage in the individual and collective en joyment of its rights and privileges; our loyalty to the principles of the Federal Constitution; the co-existence in Puerto Rico of the two great cultures of the American Hemisphere; our fervor for education; our faith in justice; our devotion to the courageous, in dustrious, and peaceful way of life; our fidelity to individual human values above and beyond social position, racial differences, and economic interests; and our hope for a better world based on these principles.” From the Preamble to the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico July 25,1952.. ii PREFACE This study is more than a dissertation because it seeks to appraise a decade of Industrial Education in Puerto Rico in the light of the economic and cultural advancements made, and then in the field work required, to stimulate the further development involved in this, as well as in other parts of the free world. -

Sloyd Gustaf Larsson

Sloyd GustafLarsson HARVARD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION SLOYD BY GUSTAF LARSSON PRINCIPAL SLOYD TRAINING SCHOOL BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS Tr/f-7 hajwmid unrmsm OIUBOATE SCHOOt Of EDUCATION Copyright Br Gustaf Larsson •9" TO MRS. OUINCY A. SHAW IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF HER INSPIRING SYMPATHY AND CO-OPERATION IN MY WORK IT PREFACE. The following papers have been collected and printed at the re quest of several friends, who have felt that the educational char acter and the universal need of Sloyd should be better and more generally understood. These papers have been read at different times and places, and consequently contain some unavoidable repe tition. Unfortunately, Sloyd has often been superficially judged from its outward symbols only, while the vital principles for which it stands have been overlooked. It is hoped that this little publica tion may help to convince teachers and other promoters of educa tion that the principles of Sloyd are broad and universal, and that as an effective educational agent it deserves a place in our schools. I am greatly indebted to my fellow-workers for valuable aid and suggestions in preparing these papers, especially to the teachers and friends of the Sloyd Training School, who have earnestly co operated with me in the work. GUSTAF LARSSON. Sloyd Training School, Boston, Massachusetts, May, 1902. CONTENTS. Paper Page I. Educational Manual Training or Sloyd. Illustrated. Read before the National Summer School, Glens Falls, N.Y., July, 1 891 9 II. Sloyd for Elementary Schools, as Contrasted with the Russian System of Manual Training. Illustrated. Read at the International Congress of Education of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, July 26, 1893, 19 III.