DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 441 SP 030 865 TITLE Detection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

WO 2013/169741 Al 14 November 2013 (14.11.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/169741 Al 14 November 2013 (14.11.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/401 (2006.01) A61P 9/12 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 31/405 (2006.01) A61P 25/00 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, A61K 31/7048 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, PCT/US20 13/039904 KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (22) International Filing Date: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 7 May 2013 (07.05.2013) NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (25) Filing Language: English TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, (26) Publication Language: English ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/644,134 8 May 2012 (08.05.2012) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (72) Inventors; and UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (71) Applicants : STEIN, Emily A. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2012/0115729 A1 Qin Et Al

US 201201.15729A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2012/0115729 A1 Qin et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 10, 2012 (54) PROCESS FOR FORMING FILMS, FIBERS, Publication Classification AND BEADS FROM CHITNOUS BOMASS (51) Int. Cl (75) Inventors: Ying Qin, Tuscaloosa, AL (US); AOIN 25/00 (2006.01) Robin D. Rogers, Tuscaloosa, AL A6II 47/36 (2006.01) AL(US); (US) Daniel T. Daly, Tuscaloosa, tish 9.8 (2006.01)C (52) U.S. Cl. ............ 504/358:536/20: 514/777; 426/658 (73) Assignee: THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 57 ABSTRACT ALABAMA, Tuscaloosa, AL (US) (57) Disclosed is a process for forming films, fibers, and beads (21) Appl. No.: 13/375,245 comprising a chitinous mass, for example, chitin, chitosan obtained from one or more biomasses. The disclosed process (22) PCT Filed: Jun. 1, 2010 can be used to prepare films, fibers, and beads comprising only polymers, i.e., chitin, obtained from a suitable biomass, (86). PCT No.: PCT/US 10/36904 or the films, fibers, and beads can comprise a mixture of polymers obtained from a suitable biomass and a naturally S3712). (4) (c)(1), Date: Jan. 26, 2012 occurring and/or synthetic polymer. Disclosed herein are the (2), (4) Date: an. AO. films, fibers, and beads obtained from the disclosed process. O O This Abstract is presented solely to aid in searching the sub Related U.S. Application Data ject matter disclosed herein and is not intended to define, (60)60) Provisional applicationpp No. 61/182,833,sy- - - s filed on Jun. -

Association of Oral Anticoagulants and Proton Pump Inhibitor Cotherapy with Hospitalization for Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding

Supplementary Online Content Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of oral anticoagulants and proton pump inhibitor cotherapy with hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.17242 eAppendix. PPI Co-therapy and Anticoagulant-Related UGI Bleeds This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 Appendix: PPI Co-therapy and Anticoagulant-Related UGI Bleeds Table 1A Exclusions: end-stage renal disease Diagnosis or procedure code for dialysis or end-stage renal disease outside of the hospital 28521 – anemia in ckd 5855 – Stage V , ckd 5856 – end stage renal disease V451 – Renal dialysis status V560 – Extracorporeal dialysis V561 – fitting & adjustment of extracorporeal dialysis catheter 99673 – complications due to renal dialysis CPT-4 Procedure Codes 36825 arteriovenous fistula autogenous gr 36830 creation of arteriovenous fistula; 36831 thrombectomy, arteriovenous fistula without revision, autogenous or 36832 revision of an arteriovenous fistula, with or without thrombectomy, 36833 revision, arteriovenous fistula; with thrombectomy, autogenous or nonaut 36834 plastic repair of arteriovenous aneurysm (separate procedure) 36835 insertion of thomas shunt 36838 distal revascularization & interval ligation, upper extremity 36840 insertion mandril 36845 anastomosis mandril 36860 cannula declotting; 36861 cannula declotting; 36870 thrombectomy, percutaneous, arteriovenous -

Initial Medication Selection for Treatment of Hypertension in an Open-Panel HMO

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.8.1.1 on 1 January 1995. Downloaded from Initial Medication Selection For Treatment Of Hypertension In An Open-Panel HMO Micky jerome, PharmD, MBA, George C. Xakellis, MD, Greg Angstman, MD, and Wayne Patchin, MBA Background: During the past 25 years recommendations for treating hypertension have evolved from a stepped-care approach to monotherapy or sequential monotherapy as experience has been gained and new antihypertensive agents have been introduced. In an effort to develop a disease management strategy for hypertension, we investigated the prescribing patterns of initial medication therapy for newly treated hypertensive patients. Methods: We examined paid claims data of an open-panel HMO located in the midwest. Charts from 377 patients with newly treated hypertension from a group of 12,242 hypertenSive patients in a health insurance population of 85,066 persons were studied. The type of medication regimen received by patients newly treated for hypertension during an 18-month period was categorized into monotherapy, sequential monotherapy, stepped care, and initial treatment with multiple agents. With monotherapy, the class of medication was also reported. Associations between use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, or (3-blockers and presence of comorbid conditions were reported. Results: Fifty-five percent of patients received monotherapy, 22 percent received stepped care, and 18 percent received sequential monotherapy. Of those 208 patients receiving monotherapy, 30 percent were prescribed a calcium channel blocker, 22 percent an ACE inhibitor, and 14 percent a f3-blocker. No customization of treatment for comorbid conditions was noted. -

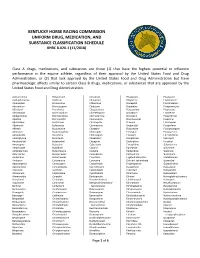

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Long Acting, Reversible Veterinary Sedative and Analgesic And

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Veterinary Science Faculty Patents Veterinary Science 7-11-2006 Long Acting, Reversible Veterinary Sedative and Analgesic and Method of Use Thomas Tobin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gluck_patents Part of the Veterinary Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Tobin, Thomas, "Long Acting, Reversible Veterinary Sedative and Analgesic and Method of Use" (2006). Veterinary Science Faculty Patents. 14. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gluck_patents/14 This Patent is brought to you for free and open access by the Veterinary Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Veterinary Science Faculty Patents by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. US007074834B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 7,074,834 B2 Tobin (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 11, 2006 (54) LONG ACTING, REVERSIBLE VETERINARY 4,742,054 A 5/1988 Naftchi SEDATIVE AND ANALGESIC AND METHOD 4,950,648 A 8/1990 Raddatz et a1. OF USE 5,635,204 A * 6/1997 GevirtZ et a1. ............ .. 424/449 5,942,241 A 8/1999 Chasin et a1. (75) Inventor: Thomas Tobin, Lexington, KY (US) 5,958,933 A 9/1999 Naftchi (73) Assignee: University of Kentucky Foundation, OTHER PUBLICATIONS Lexington, KY (US) MEDLINE AN 20000025586, Veveris et al, Brit. J. Pharmacol, 128 (5), 1089-97, Nov. 1999, abstract.* ( * ) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Adams, pp. -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Dental Management for the Hypertensive Patient

HYPERTENSION AND ORAL HEALTH: EPIDEMIOLOGIC AND CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES Janet H Southerland, DDS, MPH, PhD Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery School of Dentistry, Meharry Medical College December 9, 2016 Provide an overview of concerns with treating patients with hypertension and GOAL provide recommendations that will be helpful in managing a broad spectrum of these patients. EVALUATION Evaluation for hypertension has three objectives: 1. to assess lifestyle and identify other cardiovascular risk factors or concomitant disorders that may affect prognosis and guide treatment. 2. to reveal identifiable causes of high BP. 3. to assess the presence or absence of target organ damage and cardiovascular disease (CVD). TARGET ORGAN DAMAGE Heart Left ventricular hypertrophy Angina or prior myocardial infarction Prior coronary revascularization Heart Failure Brain Stroke or transient ischemic attack Chronic kidney disease Peripheral artery disease Retinopathy The relationship between BP and risk of CVD events is continuous, consistent, and independent of other risk factors. The higher the BP, the greater is the chance of heart attack, heart failure, stroke, and kidney disease. INTRODUCTION The risk of developing CVD doubles for every increment of 20 mm Hg Systolic (SBP) or 10 mm Hg of Diastolic (DBP). The risk of dying of ischemic heart disease and stroke increases progressively and linearly when blood pressure exceeds 115/75 mm Hg. The 7th and 8th Joint National Committee (JNC-7 and 8) reports provide guidelines for blood pressure management and treatment. The JNC-8 panel confirms that the >140/90 mmHg definition for hypertension from the INTRODUCTION JNC 7 report remains the standard for diagnosis for individuals who do not have additional comorbidities. -

Systematic Evidence Review from the Blood Pressure Expert Panel, 2013

Managing Blood Pressure in Adults Systematic Evidence Review From the Blood Pressure Expert Panel, 2013 Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................ vi Blood Pressure Expert Panel ..............................................................................................................vii Section 1: Background and Description of the NHLBI Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Project ............ 1 A. Background .............................................................................................................................. 1 Section 2: Process and Methods Overview ......................................................................................... 3 A. Evidence-Based Approach ....................................................................................................... 3 i. Overview of the Evidence-Based Methodology ................................................................. 3 ii. System for Grading the Body of Evidence ......................................................................... 4 iii. Peer-Review Process ....................................................................................................... 5 B. Critical Question–Based Approach ........................................................................................... 5 i. How the Questions Were Selected ................................................................................... 5 ii. Rationale for the Questions -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0