Comment Letter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebooks-Civil Cover Sheet

, J:a 44C/SDNY COVE ~/21112 REV: CiV,L: i'l2 CW r 6·· .,.. The JS44 civil cover sheet and the information contained herein neither replace nor supplement the fiOm ic G) pleadings or other papers as required by law, except as provided by local rules of court. This form, approved IJ~ JUdicial Conference of the United Slates in September 1974, is required for use of the Clerk of Court for the purpose of 5 initiating the civil docket sheet. ~=:--- -:::-=:-:::-:-:-:~ ~AUG 292012 PLAINTIFFS DEFENDANTS State of Texas, State of Connecticut, State of Ohio, et. al (see attached Hachette Book Group, Inc; HarperCollins Publishers, LLC; Simon & Schuster, sheets for Additional Plaintiffs) Inc; and Simon & Schuster Digital Sales, Inc. ATIORNEYS (FIRM NAME, ADDRESS, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER ATIORNEYS (IF KNOWN) Rebecca Fisher, TX Att-j Gan.Off. P.O.Box 12548. Austin TX 78711-12548, Paul Yde. Freshflelds, 701 Pennsylvania Ave., NW, Washington D.C. 20004 512463-1265: (See attached sheets for additional Plaintiff Attomey contact 2692: Clifford Aronson, Skadden Arps, 4 Times Sq., NY, NY 10036-6522; information) Helene Jaffe, Prosknuer Rose,LLP, Eleven Times Square, NY, NY 10036 CAUSE OF ACTION (CITE THE U.S. CIVIL STATUTE UNDER WHICH YOU ARE FILING AND WRITE A BRIEF STATEMENT OF CAUSE) (DO NOT CITE JURISDICTIONAL STATUTES UNLESS DIVERSITY) 15 USC §1 and 15 USC §§15c & 26. Plaintiffs allege Defendants entered illegal contracts and conspiracies in restraint of trade for e-books. Has this or a similar case been previously filed in SONY at any time? No 0 Yes 0 Judge Previously Assigned Judge Denise Cote If yes, was lhis case Vol. -

What the United States Can Learn from the New French Law on Consumer Overindebtedness

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 26 Issue 2 2005 La Responsabilisation de L'economie: What the United States Can Learn from the New French Law on Consumer Overindebtedness Jason J. Kilborn Louisiana State University Paul M. Hebert Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Jason J. Kilborn, La Responsabilisation de L'economie: What the United States Can Learn from the New French Law on Consumer Overindebtedness, 26 MICH. J. INT'L L. 619 (2005). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol26/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LA RESPONSABILISATION DE L'ECONOMIE:t WHAT THE UNITED STATES CAN LEARN FROM THE NEW FRENCH LAW ON CONSUMER OVERINDEBTEDNESS Jason J. Kilborn* I. THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF CREDIT IN A CREDITOR-FRIENDLY LEGAL SYSTEM ......................................623 A. Deregulationof Consumer Credit and the Road to O ver-indebtedness............................................................. 624 B. A Legal System Ill-Equipped to Deal with Overburdened Consumers .................................................627 1. Short-Term Payment Deferrals ...................................628 2. Restrictions on Asset Seizure ......................................629 3. Wage Exem ptions .......................................................630 II. THE BIRTH AND GROWTH OF THE FRENCH LAW ON CONSUMER OVER-INDEBTEDNESS ............................................632 A. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 11-564 In the Supreme Court of the United States FLORIDA , Petitioner , v. JOELIS JARDINES , Respondent . On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida BRIEF OF TEXAS , ALABAMA , ARIZONA , COLORADO , DELAWARE , GUAM , HAWAII , IDAHO , IOWA , KANSAS , KENTUCKY , LOUISIANA , MICHIGAN , NEBRASKA , NEW MEXICO , TENNESSEE , UTAH , VERMONT , AND VIRGINIA AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER GREG ABBOTT ADAM W. ASTON Attorney General of Assistant Solicitor Texas General Counsel of Record DANIEL T. HODGE First Assistant Attorney OFFICE OF THE General ATTORNEY GENERAL P.O. Box 12548 DON CLEMMER Austin, Texas 78711-2548 Deputy Attorney General [Tel.] (512) 936-0596 for Criminal Justice [email protected] JONATHAN F. MITCHELL Solicitor General COUNSEL FOR AMICI CURIAE [Additional counsel listed on inside cover] ADDITIONAL COUNSEL LUTHER STRANGE Attorney General of Alabama TOM HORNE Attorney General of Arizona JOHN W. SUTHERS Attorney General of Colorado JOSEPH R. BIDEN, III Attorney General of Delaware LEONARDO M. RAPADAS Attorney General of Guam DAVID M. LOUIE Attorney General of Hawaii LAWRENCE G. WASDEN Attorney General of Idaho ERIC J. TABOR Attorney General of Iowa DEREK SCHMIDT Attorney General of Kansas JACK CONWAY Attorney General of Kentucky JAMES D. “BUDDY” CALDWELL Attorney General of Louisiana BILL SCHUETTE Attorney General of Michigan JON BRUNING Attorney General of Nebraska GARY KING Attorney General of New Mexico ROBERT E. COOPER, JR. Attorney General of Tennessee MARK L. SHURTLEFF Attorney General of Utah WILLIAM H. SORRELL Attorney General of Vermont KENNETH T. CUCCINELLI, II Attorney General of Virginia i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities ........................ -

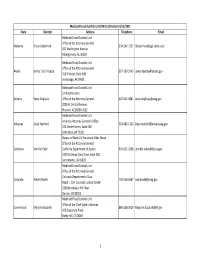

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alabama Bruce Lieberman 334‐242‐7327 [email protected] 501 Washington Avenue Montgomery, AL 36130 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alaska James "Jay" Fayette 907‐269‐5140 [email protected] 310 K Street, Suite 308 Anchorage, AK 99501 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Criminal Division Arizona Steve Duplissis Office of the Attorney General 602‐542‐3881 [email protected] 2005 N. Central Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85004‐1592 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Arkansas Attorney General's Office Arkansas Lloyd Warford 501‐682‐1320 [email protected] 323 Center Street, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Bureau of Medi‐Cal Fraud and Elder Abuse Office of the Attorney General California Jennifer Euler California Department of Justice 916‐621‐1858 [email protected] 2329 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 200 Sacramento, CA 95833 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Colorado Department of Law Colorado Robert Booth 720‐508‐6687 [email protected] Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center 1300 Broadway, 9th Floor Denver, CO 80203 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Chief State's Attorney Connecticut Marjorie Sozanski 860‐258‐5929 [email protected] 300 Corporate Place Rocky Hill, CT 06067 1 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Delaware Edward Black (Acting) 302‐577‐4209 [email protected] 820 N French Street, 5th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit District of Office of D.C. -

Brief of Petitioner for Howes V. Fields, 10-680

No. 10-680 In the Supreme Court of the United States ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ CAROL HOWES, Petitioner, v. RANDALL FIELDS, Respondent. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE OF OHIO, ALABAMA, ALASKA, ARIZONA, ARKANSAS, COLORADO, DELAWARE, FLORIDA, GUAM, HAWAII, IDAHO, ILLINOIS, INDIANA, IOWA, KANSAS, KENTUCKY, LOUISIANA, MAINE, MARYLAND, MONTANA, NEBRASKA, NEVADA, NEW HAMPSHIRE, NEW MEXICO, NORTH DAKOTA, PENNSYLVANIA, SOUTH CAROLINA, SOUTH DAKOTA, TENNESSEE, TEXAS, UTAH, VERMONT, VIRGINIA, WASHINGTON, WISCONSIN, AND WYOMING IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ MICHAEL DEWINE Attorney General of Ohio ALEXANDRA T. SCHIMMER* Solicitor General *Counsel of Record DAVID M. LIEBERMAN Deputy Solicitor 30 East Broad St., 17th Floor Columbus, Ohio 43215 614-466-8980 Counsel for Amici Curiae LUTHER STRANGE LISA MADIGAN Attorney General Attorney General State of Alabama State of Illinois JOHN J. BURNS GREGORY F. ZOELLER Attorney General Attorney General State of Alaska State of Indiana TOM HORNE TOM MILLER Attorney General Attorney General State of Arizona State of Iowa DUSTIN MCDANIEL DEREK SCHMIDT Attorney General Attorney -

VAWA”) Has Shined a Bright Light on Domestic Violence, Bringing the Issue out of the Shadows and Into the Forefront of Our Efforts to Protect Women and Families

January 11, 2012 Dear Members of Congress, Since its passage in 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (“VAWA”) has shined a bright light on domestic violence, bringing the issue out of the shadows and into the forefront of our efforts to protect women and families. VAWA transformed the response to domestic violence at the local, state and federal level. Its successes have been dramatic, with the annual incidence of domestic violence falling by more than 50 percent1. Even though the advancements made since in 1994 have been significant, a tremendous amount of work remains and we believe it is critical that the Congress reauthorize VAWA. Every day in this country, abusive husbands or partners kill three women, and for every victim killed, there are nine more who narrowly escape that fate2. We see this realized in our home states every day. Earlier this year in Delaware, three children – ages 12, 2 ½ and 1 ½ − watched their mother be beaten to death by her ex-boyfriend on a sidewalk. In Maine last summer, an abusive husband subject to a protective order murdered his wife and two young children before taking his own life. Reauthorizing VAWA will send a clear message that this country does not tolerate violence against women and show Congress’ commitment to reducing domestic violence, protecting women from sexual assault and securing justice for victims. VAWA reauthorization will continue critical support for victim services and target three key areas where data shows we must focus our efforts in order to have the greatest impact: • Domestic violence, dating violence, and sexual assault are most prevalent among young women aged 16-24, with studies showing that youth attitudes are still largely tolerant of violence, and that women abused in adolescence are more likely to be abused again as adults. -

A Survey of Five Taft's Flat Neighborhoods

A Survey of Five Taft’s Flat Neighborhoods: Victory Circle/Highland Avenue Watson Plaza Highland Park Demers Avenue Manning Park Manning Park Extension Presented to Hartford Historic Preservation Commission Hartford, Vermont By Brian Knight Research P.O. Box 1096 Manchester, Vermont 05254 June 4, 2020 Draft Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Hartford Background ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Period of Significance ....................................................................................................................................... 5 About the Hartford Historic Preservation Commission ................................................................ 5 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 National Register of Historic Places/State Register of Historic Places .................................. 7 Demers Avenue ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Worcester Avenue ........................................................................................................................................... 11 Victory Circle ...................................................................................................................................................... -

January 12, 2021 the Honorable Jeffrey A. Rosen Acting Attorney

January 12, 2021 The Honorable Jeffrey A. Rosen Acting Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, DC 20530 Dear Acting Attorney General Rosen: We, the undersigned state attorneys general, are committed to the protection of public safety, the rule of law, and the U.S. Constitution. We are appalled that on January 6, 2021, rioters invaded the U.S. Capitol, defaced the building, and engaged in a range of criminal conduct—including unlawful entry, theft, destruction of U.S. government property, and assault. Worst of all, the riot resulted in the deaths of individuals, including a U.S. Capitol Police officer, and others were physically injured. Beyond these harms, the rioters’ actions temporarily paused government business of the most sacred sort in our system—certifying the result of a presidential election. We all just witnessed a very dark day in America. The events of January 6 represent a direct, physical challenge to the rule of law and our democratic republic itself. Together, we will continue to do our part to repair the damage done to institutions and build a more perfect union. As Americans, and those charged with enforcing the law, we must come together to condemn lawless violence, making clear that such actions will not be allowed to go unchecked. Thank you for your consideration of and work on this crucial priority. Sincerely Phil Weiser Karl A. Racine Colorado Attorney General District of Columbia Attorney General Lawrence Wasden Douglas Peterson Idaho Attorney General Nebraska Attorney General Steve Marshall Clyde “Ed” Sniffen, Jr. Alabama Attorney General Acting Alaska Attorney General Mark Brnovich Leslie Rutledge Arizona Attorney General Arkansas Attorney General Xavier Becerra William Tong California Attorney General Connecticut Attorney General Kathleen Jennings Ashley Moody Delaware Attorney General Florida Attorney General Christopher M. -

Graham & Doddsville

Graham & Doddsville An investment newsletter from the students of Columbia Business School Inside this issue: Issue XXX Spring 2017 CSIMA ARGA Investment Management Conference P. 3 Pershing Square A. Rama Krishna, CFA, is the founder and Chief Investment Challenge P. 4 Officer of ARGA Investment Management. He was previously A. Rama Krishna P. 5 President, International of Pzena Investment Management and Managing Principal, Member of Executive Committee, and Cliff Sosin P. 14 Portfolio Manager of its operating company in New York. He led the development of the firm's International Value and Student Ideas P. 28 Global Value strategies and co-managed the Emerging Markets Chris Begg P. 36 Value strategy, in addition to managing the U.S. Large Cap A. Rama Krishna Value strategy in his early years at Pzena. Prior to joining Pzena in 2003, Mr. Krishna was at Citigroup Asset Editors: (Continued on page 5) CAS Investment Partners Eric Laidlow, CFA MBA 2017 Cliff Sosin is the founder and investment manager of CAS Benjamin Ostrow Investment Partners, LLC ("CAS"), which he launched in MBA 2017 October 2012. Immediately prior to founding CAS, Cliff was a John Pollock, CFA Director in the Fundamental Investment Group of UBS for five MBA 2017 years where he was a senior member of a team analyzing equities and fixed income securities. Prior to UBS, Cliff was Abheek Bhattacharya employed as an analyst by Silver Point Capital, a hedge fund MBA 2018 which invested in high yield and distressed opportunities, as well as by Houlihan Lokey Howard & Zukin, a leading Matthew Mann, CFA investment bank best known for its advisory services with MBA 2018 Clifford Sosin respect to companies requiring financial restructuring. -

Little Caesars And/Or Its Franchisees

SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE STATES OF MASSACHUSETTS, CALIFORNIA, ILLINOIS, IOWA, MARYLAND, MINNESOTA, NEW JERSEY, NEW YORK, NORTH CAROLINA, OREGON, PENNSYLVANIA, RHODE ISLAND, VERMONT, AND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AND LITTLE CAESAR ENTERPRISES, INC. PARTIES 1. The States of Massachusetts, California, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont, and the District of Columbia (the “Settling States”), by and through their Attorneys General (collectively, “the Attorneys General”), are charged with enforcement of, among other things, their respective state’s consumer protection and antitrust laws, and other related statutes and regulations. 2. Little Caesar Enterprises, Inc. (“Little Caesar”) is a Michigan corporation with its principal offices or place of business in Detroit, Michigan. Little Caesar is owned by Ilitch Holdings, Inc., a holding company headquartered in Detroit, MI. Little Caesar is a franchisor, and its corporate and franchisee-operated locations are in the business of offering pizza, among other food products, for sale to consumers. DEFINITIONS 3. For purposes of this Settlement Agreement, “No-Poach Provisions” refers to any and all language contained within franchise or license agreements or any other documents which restricts, limits or prevents any Little Caesar franchisee or Little Caesar-operated restaurant from hiring, recruiting or soliciting employees of Little Caesar and/or any other Little Caesar franchisee for employment. Such language includes, but is not limited to, any “no-solicitation,” “no switching,” and/or “no-hire” provisions. 4. “Little Caesar” shall mean Little Caesar Enterprises, Inc. and shall include its directors, officers, managers, agents acting within the scope of their agency, and employees as well as its successors and assigns, controlled subsidiaries, and predecessor franchisor entities. -

For Immediate Release News Release 2021-34 May 13, 2021

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR CLARE E. CONNORS ATTORNEY GENERAL For Immediate Release News Release 2021-34 May 13, 2021 Hawaii Attorney General Clare E. Connors Joins Coalition of 44 Attorneys General Urging Facebook to Abandon Launch of Instagram Kids HONOLULU – Attorney General Clare E. Connors joined a coalition of 44 attorneys general led by Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, Nebraska Attorney General Douglas Peterson, Tennessee Attorney General Herbert H. Slatery III and Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan urging Facebook to abandon its plans to launch a version of Instagram for children under the age of 13, citing serious concerns about the safety and well-being of children and the harm social media poses to young people. In a letter to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, the coalition contends that social media can be detrimental to children for myriad reasons and that Facebook has historically failed to protect the welfare of children on its platforms. “Research shows that social media use by our young children is detrimental to their development and mental health, which means companies such as Facebook should strive to protect them from harm rather than benefit from their vulnerabilities,” said Attorney General Connors. “I urge Facebook to consider the well-researched evidence of harm that a social media platform targeting children under the age of 13 could cause and to abandon further development.” In their letter, the attorneys general express various concerns over Facebook’s proposal, including research that social media can be harmful to the physical, emotional, and mental well-being of children; rapidly worsening concerns about cyber bullying on Instagram; use of the platform by predators to target children; Facebook’s checkered record in protecting the welfare of children on its platforms; and children’s lack of capacity to navigate the complexities of what they encounter online, including advertising, inappropriate content and relationships with strangers. -

Ontario Superior Court of Justice Commercial List

Court File No. CV-17-587463-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST B E T W E E N: THE CATALYST CAPITAL GROUP and CALLIDUS CAPITAL CORPORATION Plaintiffs - and - WEST FACE CAPITAL INC., GREGORY BOLAND, M5V ADVISORS INC. C.O.B. ANSON GROUP CANADA, ADMIRALTY ADVISORS LLC, FRIGATE VENTURES LP, ANSON INVESTMENTS LP, ANSON CAPITAL LP, ANSON INVESTMENTS MASTER FUND LP, AIMF GP, ANSON CATALYST MASTER FUND LP, ACF GP, MOEZ KASSAM, ADAM SPEARS, SUNNY PURI, CLARITYSPRING INC., NATHAN ANDERSON, BRUCE LANGSTAFF, ROB COPELAND, KEVIN BAUMANN, KEVIN BAUMANN, JEFFREY MCFARLANE, DARRYL LEVITT, RICHARD MOLYNEUX, GERALD DUHAMEL, GEORGE WESLEY VOORHEIS, BRUCE LIVESEY and JOHN DOES #4-10 Defendants WEST FACE CAPITAL INC. and GREGORY BOLAND Plaintiffs by Counterclaim - and – THE CATALYST CAPITAL GROUP INC., CALLIDUS CAPITAL CORPORATION, NEWTON GLASSMAN, GABRIEL DE ALBA, JAMES RILEY, VIRGINIA JAMIESON, EMMANUEL ROSEN, B.C. STRATEGY LTD. d/b/a BLACK CUBE, B.C. STRATEGY UK LTD. d/b/a BLACK CUBE, and INVOP LTD. d/b/a PSY GROUP INC. Defendants by Counterclaim Court File No. CV-18-593156-00CL B E T W E E N: THE CATALYST CAPITAL GROUP INC. and CALLIDUS CAPITAL CORPORATION Plaintiffs - and - DOW JONES AND COMPANY, ROB COPELAND, JACQUIE MCNISH and JEFFREY MCFARLANE Defendants MOTION RECORD (VOLUME III OF III) August 12, 2020 GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP Barristers & Solicitors 1 First Canadian Place 100 King Street West, Suite 1600 Toronto ON M5X 1G5 Tel: 416-862-7525 Fax: 416-862-7661 John E. Callaghan (LSO#29106K) [email protected] Benjamin Na (LSO#40958O) [email protected] Richard G.