Brief of Petitioner for Howes V. Fields, 10-680

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebooks-Civil Cover Sheet

, J:a 44C/SDNY COVE ~/21112 REV: CiV,L: i'l2 CW r 6·· .,.. The JS44 civil cover sheet and the information contained herein neither replace nor supplement the fiOm ic G) pleadings or other papers as required by law, except as provided by local rules of court. This form, approved IJ~ JUdicial Conference of the United Slates in September 1974, is required for use of the Clerk of Court for the purpose of 5 initiating the civil docket sheet. ~=:--- -:::-=:-:::-:-:-:~ ~AUG 292012 PLAINTIFFS DEFENDANTS State of Texas, State of Connecticut, State of Ohio, et. al (see attached Hachette Book Group, Inc; HarperCollins Publishers, LLC; Simon & Schuster, sheets for Additional Plaintiffs) Inc; and Simon & Schuster Digital Sales, Inc. ATIORNEYS (FIRM NAME, ADDRESS, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER ATIORNEYS (IF KNOWN) Rebecca Fisher, TX Att-j Gan.Off. P.O.Box 12548. Austin TX 78711-12548, Paul Yde. Freshflelds, 701 Pennsylvania Ave., NW, Washington D.C. 20004 512463-1265: (See attached sheets for additional Plaintiff Attomey contact 2692: Clifford Aronson, Skadden Arps, 4 Times Sq., NY, NY 10036-6522; information) Helene Jaffe, Prosknuer Rose,LLP, Eleven Times Square, NY, NY 10036 CAUSE OF ACTION (CITE THE U.S. CIVIL STATUTE UNDER WHICH YOU ARE FILING AND WRITE A BRIEF STATEMENT OF CAUSE) (DO NOT CITE JURISDICTIONAL STATUTES UNLESS DIVERSITY) 15 USC §1 and 15 USC §§15c & 26. Plaintiffs allege Defendants entered illegal contracts and conspiracies in restraint of trade for e-books. Has this or a similar case been previously filed in SONY at any time? No 0 Yes 0 Judge Previously Assigned Judge Denise Cote If yes, was lhis case Vol. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 11-564 In the Supreme Court of the United States FLORIDA , Petitioner , v. JOELIS JARDINES , Respondent . On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida BRIEF OF TEXAS , ALABAMA , ARIZONA , COLORADO , DELAWARE , GUAM , HAWAII , IDAHO , IOWA , KANSAS , KENTUCKY , LOUISIANA , MICHIGAN , NEBRASKA , NEW MEXICO , TENNESSEE , UTAH , VERMONT , AND VIRGINIA AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER GREG ABBOTT ADAM W. ASTON Attorney General of Assistant Solicitor Texas General Counsel of Record DANIEL T. HODGE First Assistant Attorney OFFICE OF THE General ATTORNEY GENERAL P.O. Box 12548 DON CLEMMER Austin, Texas 78711-2548 Deputy Attorney General [Tel.] (512) 936-0596 for Criminal Justice [email protected] JONATHAN F. MITCHELL Solicitor General COUNSEL FOR AMICI CURIAE [Additional counsel listed on inside cover] ADDITIONAL COUNSEL LUTHER STRANGE Attorney General of Alabama TOM HORNE Attorney General of Arizona JOHN W. SUTHERS Attorney General of Colorado JOSEPH R. BIDEN, III Attorney General of Delaware LEONARDO M. RAPADAS Attorney General of Guam DAVID M. LOUIE Attorney General of Hawaii LAWRENCE G. WASDEN Attorney General of Idaho ERIC J. TABOR Attorney General of Iowa DEREK SCHMIDT Attorney General of Kansas JACK CONWAY Attorney General of Kentucky JAMES D. “BUDDY” CALDWELL Attorney General of Louisiana BILL SCHUETTE Attorney General of Michigan JON BRUNING Attorney General of Nebraska GARY KING Attorney General of New Mexico ROBERT E. COOPER, JR. Attorney General of Tennessee MARK L. SHURTLEFF Attorney General of Utah WILLIAM H. SORRELL Attorney General of Vermont KENNETH T. CUCCINELLI, II Attorney General of Virginia i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities ........................ -

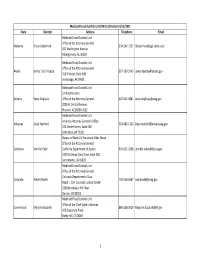

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alabama Bruce Lieberman 334‐242‐7327 [email protected] 501 Washington Avenue Montgomery, AL 36130 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alaska James "Jay" Fayette 907‐269‐5140 [email protected] 310 K Street, Suite 308 Anchorage, AK 99501 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Criminal Division Arizona Steve Duplissis Office of the Attorney General 602‐542‐3881 [email protected] 2005 N. Central Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85004‐1592 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Arkansas Attorney General's Office Arkansas Lloyd Warford 501‐682‐1320 [email protected] 323 Center Street, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Bureau of Medi‐Cal Fraud and Elder Abuse Office of the Attorney General California Jennifer Euler California Department of Justice 916‐621‐1858 [email protected] 2329 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 200 Sacramento, CA 95833 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Colorado Department of Law Colorado Robert Booth 720‐508‐6687 [email protected] Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center 1300 Broadway, 9th Floor Denver, CO 80203 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Chief State's Attorney Connecticut Marjorie Sozanski 860‐258‐5929 [email protected] 300 Corporate Place Rocky Hill, CT 06067 1 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Delaware Edward Black (Acting) 302‐577‐4209 [email protected] 820 N French Street, 5th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit District of Office of D.C. -

VAWA”) Has Shined a Bright Light on Domestic Violence, Bringing the Issue out of the Shadows and Into the Forefront of Our Efforts to Protect Women and Families

January 11, 2012 Dear Members of Congress, Since its passage in 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (“VAWA”) has shined a bright light on domestic violence, bringing the issue out of the shadows and into the forefront of our efforts to protect women and families. VAWA transformed the response to domestic violence at the local, state and federal level. Its successes have been dramatic, with the annual incidence of domestic violence falling by more than 50 percent1. Even though the advancements made since in 1994 have been significant, a tremendous amount of work remains and we believe it is critical that the Congress reauthorize VAWA. Every day in this country, abusive husbands or partners kill three women, and for every victim killed, there are nine more who narrowly escape that fate2. We see this realized in our home states every day. Earlier this year in Delaware, three children – ages 12, 2 ½ and 1 ½ − watched their mother be beaten to death by her ex-boyfriend on a sidewalk. In Maine last summer, an abusive husband subject to a protective order murdered his wife and two young children before taking his own life. Reauthorizing VAWA will send a clear message that this country does not tolerate violence against women and show Congress’ commitment to reducing domestic violence, protecting women from sexual assault and securing justice for victims. VAWA reauthorization will continue critical support for victim services and target three key areas where data shows we must focus our efforts in order to have the greatest impact: • Domestic violence, dating violence, and sexual assault are most prevalent among young women aged 16-24, with studies showing that youth attitudes are still largely tolerant of violence, and that women abused in adolescence are more likely to be abused again as adults. -

A Survey of Five Taft's Flat Neighborhoods

A Survey of Five Taft’s Flat Neighborhoods: Victory Circle/Highland Avenue Watson Plaza Highland Park Demers Avenue Manning Park Manning Park Extension Presented to Hartford Historic Preservation Commission Hartford, Vermont By Brian Knight Research P.O. Box 1096 Manchester, Vermont 05254 June 4, 2020 Draft Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Hartford Background ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Period of Significance ....................................................................................................................................... 5 About the Hartford Historic Preservation Commission ................................................................ 5 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 National Register of Historic Places/State Register of Historic Places .................................. 7 Demers Avenue ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Worcester Avenue ........................................................................................................................................... 11 Victory Circle ...................................................................................................................................................... -

January 12, 2021 the Honorable Jeffrey A. Rosen Acting Attorney

January 12, 2021 The Honorable Jeffrey A. Rosen Acting Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, DC 20530 Dear Acting Attorney General Rosen: We, the undersigned state attorneys general, are committed to the protection of public safety, the rule of law, and the U.S. Constitution. We are appalled that on January 6, 2021, rioters invaded the U.S. Capitol, defaced the building, and engaged in a range of criminal conduct—including unlawful entry, theft, destruction of U.S. government property, and assault. Worst of all, the riot resulted in the deaths of individuals, including a U.S. Capitol Police officer, and others were physically injured. Beyond these harms, the rioters’ actions temporarily paused government business of the most sacred sort in our system—certifying the result of a presidential election. We all just witnessed a very dark day in America. The events of January 6 represent a direct, physical challenge to the rule of law and our democratic republic itself. Together, we will continue to do our part to repair the damage done to institutions and build a more perfect union. As Americans, and those charged with enforcing the law, we must come together to condemn lawless violence, making clear that such actions will not be allowed to go unchecked. Thank you for your consideration of and work on this crucial priority. Sincerely Phil Weiser Karl A. Racine Colorado Attorney General District of Columbia Attorney General Lawrence Wasden Douglas Peterson Idaho Attorney General Nebraska Attorney General Steve Marshall Clyde “Ed” Sniffen, Jr. Alabama Attorney General Acting Alaska Attorney General Mark Brnovich Leslie Rutledge Arizona Attorney General Arkansas Attorney General Xavier Becerra William Tong California Attorney General Connecticut Attorney General Kathleen Jennings Ashley Moody Delaware Attorney General Florida Attorney General Christopher M. -

Little Caesars And/Or Its Franchisees

SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE STATES OF MASSACHUSETTS, CALIFORNIA, ILLINOIS, IOWA, MARYLAND, MINNESOTA, NEW JERSEY, NEW YORK, NORTH CAROLINA, OREGON, PENNSYLVANIA, RHODE ISLAND, VERMONT, AND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AND LITTLE CAESAR ENTERPRISES, INC. PARTIES 1. The States of Massachusetts, California, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont, and the District of Columbia (the “Settling States”), by and through their Attorneys General (collectively, “the Attorneys General”), are charged with enforcement of, among other things, their respective state’s consumer protection and antitrust laws, and other related statutes and regulations. 2. Little Caesar Enterprises, Inc. (“Little Caesar”) is a Michigan corporation with its principal offices or place of business in Detroit, Michigan. Little Caesar is owned by Ilitch Holdings, Inc., a holding company headquartered in Detroit, MI. Little Caesar is a franchisor, and its corporate and franchisee-operated locations are in the business of offering pizza, among other food products, for sale to consumers. DEFINITIONS 3. For purposes of this Settlement Agreement, “No-Poach Provisions” refers to any and all language contained within franchise or license agreements or any other documents which restricts, limits or prevents any Little Caesar franchisee or Little Caesar-operated restaurant from hiring, recruiting or soliciting employees of Little Caesar and/or any other Little Caesar franchisee for employment. Such language includes, but is not limited to, any “no-solicitation,” “no switching,” and/or “no-hire” provisions. 4. “Little Caesar” shall mean Little Caesar Enterprises, Inc. and shall include its directors, officers, managers, agents acting within the scope of their agency, and employees as well as its successors and assigns, controlled subsidiaries, and predecessor franchisor entities. -

For Immediate Release News Release 2021-34 May 13, 2021

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR CLARE E. CONNORS ATTORNEY GENERAL For Immediate Release News Release 2021-34 May 13, 2021 Hawaii Attorney General Clare E. Connors Joins Coalition of 44 Attorneys General Urging Facebook to Abandon Launch of Instagram Kids HONOLULU – Attorney General Clare E. Connors joined a coalition of 44 attorneys general led by Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, Nebraska Attorney General Douglas Peterson, Tennessee Attorney General Herbert H. Slatery III and Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan urging Facebook to abandon its plans to launch a version of Instagram for children under the age of 13, citing serious concerns about the safety and well-being of children and the harm social media poses to young people. In a letter to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, the coalition contends that social media can be detrimental to children for myriad reasons and that Facebook has historically failed to protect the welfare of children on its platforms. “Research shows that social media use by our young children is detrimental to their development and mental health, which means companies such as Facebook should strive to protect them from harm rather than benefit from their vulnerabilities,” said Attorney General Connors. “I urge Facebook to consider the well-researched evidence of harm that a social media platform targeting children under the age of 13 could cause and to abandon further development.” In their letter, the attorneys general express various concerns over Facebook’s proposal, including research that social media can be harmful to the physical, emotional, and mental well-being of children; rapidly worsening concerns about cyber bullying on Instagram; use of the platform by predators to target children; Facebook’s checkered record in protecting the welfare of children on its platforms; and children’s lack of capacity to navigate the complexities of what they encounter online, including advertising, inappropriate content and relationships with strangers. -

1.1 This Assurance of Voluntary Compliance

ASSURANCE OF VOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE In the matter of: DISH NETWORK, L.L.C., ) a Colorado Limited Liability Company ) 1.1 This Assurance of Voluntary Compliance ("Assurance")! is being entered into between the Attorneys General of Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, 2 Delaware, Florida, Georgia , Hawaie, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming (hereafter referred to as the "Attorneys General") and DISH Network, L.L.C. 1. BACKGROUND 1.2 DISH Network, L.L.C. ("DISH Network") is a limited liability company organized under the laws of the state of Colorado. Its principal place of business is located at 9601 S. Meridian Blvd, Englewood, CO 80112. 1.3 DISH Network is in the business of, among other things, providing certain audio and video progranuning services to its subscribers via direct broadcast satellites. In connection with the provision of these services, DISH Network sells and leases receiving equipment to allow access to such progranuning transmitted from such satellites. DISH Network sells and leases to its subscribers such receiving equipment both directly and through authorized retailers. 1 This Assurance of Voluntary Compliance shall, for all necessary purposes, also he considered an Assurance of Discontinuance. 2 With regard to Georgia, the Administrator of the Fair Business Practices Act, appointed pursuant to O.C.G.A. 10- 1-395, is statutorily authorized to undertake consumer protection functions, including acceptance of Assurances of Voluntary Compliance for the State of Georgia. -

June 18, 2021 Honorable Merrick B. Garland Attorney General of The

DANA NESSEL MICHIGAN ATTORNEY GENERAL June 18, 2021 Honorable Merrick B. Garland Attorney General of the United States U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Lisa O. Monaco Deputy Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Re: Department of Justice’s interpretation of Wire Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1084 Dear Attorney General Garland and Deputy Attorney General Monaco: We, the undersigned State Attorneys General, are seeking clarity and finality from the Department of Justice regarding its interpretation of the Wire Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1084. As you may be aware, 25 State Attorneys General wrote to your predecessors on March 21, 2019 to express our strong objection to the Office of Legal Counsel’s (OLC’s) Opinion “Reconsidering Whether the Wire Act Applies to Non- Sports Gambling,” which reversed the Department’s seven-year-old position that the Wire Act applied only to sports betting. Many States relied on that former position to allow online gaming to proceed. Since that letter, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit upheld a challenge to the new OLC Opinion, holding that the Wire Act applies only to sports betting. After the First Circuit decision, it is vital that States get clarity on the Department’s position going forward. States and industry participants need to understand what their rights are under the law without having to file suit in every federal circuit, and finality is needed so the industry may confidently invest in new products and features without fear of criminal prosecution. -

Dear Mr. Martin, Please See Attached in Response to Your Public Records

From: Curtis, Christopher To: [email protected] Subject: Your Public Records Request Date: Thursday, September 10, 2020 5:10:00 PM Attachments: Angelo Martin Letter 2.pdf FACEBOOK LETTER PRESS PLAN UPDATE (Letter Attached) 8_4(JRD).pdf FACEBOOK LETTER PRESS PLAN UPDATE (AND TEMPLATE RELEASE) 8_3(JRD).pdf FB Letter - Final.pdf Multistate Letter to Facebook - sign ons due COB 7_22.pdf RE_ Multistate Letter to Facebook - sign ons due COB 7_27.pdf RE_ Multistate Letter to Facebook - sign ons due COB 7_28 .pdf RE_ Multistate Letter to Facebook - sign ons due COB 7_29 (JRD).pdf RE_ Multistate Letter to Facebook - sign ons due COB 8_4.pdf Dear Mr. Martin, Please see attached in response to your public records request. Thank you. Best, Christopher Christopher J. Curtis Chief, Public Protection Division Office of the Attorney General State of Vermont 109 State Street Montpelier, VT 05609 802-828-5586 PRIVILEGED & CONFIDENTIAL COMMUNICATION: This communication may contain information that is privileged, confidential, and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. DO NOT read, copy or disseminate this communication unless you are the intended addressee. If you are not the intended recipient (or have received this E-mail in error) please notify the sender immediately and destroy this E-mail. Please consider the environment before printing this e-mail. THOMAS J. DONOVAN, JR. TEL: (802) 828-3171 ATTORNEY GENERAL http://www.ago.vermont.gov JOSHUA R. DIAMOND DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL SARAH E.B. LONDON CHIEF ASST. ATTORNEY GENERAL STATE OF VERMONT OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 109 STATE STREET MONTPELIER, VT 05609-1001 September 10, 2020 Mr. -

November 13, 2020 Via E-Mail and U.S. Mail the Honorable William

November 13, 2020 Via E-mail and U.S. Mail The Honorable William Barr U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] [email protected] Dear Attorney General Barr: The 2020 election is over, and the people of the United States have decisively chosen a new President. It is in this context that we express our deep concerns about your November 9 memorandum entitled “Post-Voting Election Irregularity Inquiry.” As the chief legal and law enforcement officers of our respective states, we recognize and appreciate the U.S. Department of Justice’s (DOJ) important role in some instances in prosecuting criminal election fraud. Yet we are alarmed by your reversal of long-standing DOJ policy that has served to facilitate that function without allowing it to interfere with election results or create the appearance of political involvement in elections. Your directive to U.S. Attorneys this week threatens to upset that critical balance, with potentially corrosive effects on the electoral processes at the heart of our democracy. State and local officials conduct our elections. Enforcement of the election laws falls primarily to the states and their subdivisions. If there has been fraud in the electoral process, the perpetrators should be brought to justice. We are committed to helping to do so. But, so far, no plausible allegations of widespread misconduct have arisen that would either impact the outcome in any state or warrant a change in DOJ policy. For 40 years, the Department of Justice has followed a policy that recognizes the states’ principal responsibility for overseeing the election process.