Belarus by Vitali Silitski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 21 TRONDHEIM STUDIES on EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES

No. 21 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES David R. Marples THE LUKASHENKA PHENOMENON Elections, Propaganda, and the Foundations of Political Authority in Belarus August 2007 David R. Marples is University Professor at the Department of History & Classics, and Director of the Stasiuk Program for the Study of Contemporary Ukraine of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. His recent books include Heroes and Villains. Constructing National History in Contemporary Ukraine (2007), Prospects for Democracy in Belarus, co-edited with Joerg Forbrig and Pavol Demes (2006), The Collapse of the Soviet Union, 1985-1991(2004), and Motherland: Russia in the 20th Century (2002). © 2007 David R Marples and the Program on East European Cultures and Societies, a program of the Faculties of Arts and Social Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. ISSN 1501-6684 ISBN 978-82-995792-1-6 Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies Editors: György Péteri and Sabrina P. Ramet Editorial Board: Trond Berge, Tanja Ellingsen, Knut Andreas Grimstad, Arne Halvorsen We encourage submissions to the Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies. Inclusion in the series will be based on anonymous review. Manuscripts are expected to be in English (exception is made for Norwegian Master’s and PhD theses) and not to exceed 150 double spaced pages in length. Postal address for submissions: Editor, Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies, Department of History, NTNU, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. For more information on PEECS and TSEECS, visit our web-site at http://www.hf.ntnu.no/peecs/home/ The photo on the cover is a copy of an item included in the photo chronicle of the demonstration of 21 July 2004 and made accessible by the Charter ’97 at http://www.charter97.org/index.phtml?sid=4&did=july21&lang=3 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES No. -

BELARUS: the Struggle for Press Freedom

International Federation of Journalists BELARUS: The Struggle for Press Freedom Belarus: The Struggle for Press Freedoom 1 1. A Brief Introduction to Belarus Widely regarded as the last true dictatorship in Europe, Belarus has been run by President Alexander Lukashenka since 1994. Belarus is bordered to the north by Latvia 2004 to allow him to stand for a third term. and Lithuania, to the east by Russia, to the International observers have consistently south by Ukraine, and to the west by Poland. raised doubts about the validity of Belarus A declining population of less than 10 million elections, and many opposition candidates inhabits its 207,595 square kilometres. were disbarred from standing in the flawed Presidential elections of March 2006. Absorbed into the Russian Empire in the Widespread protests about the outcome, middle of the 19th century, Belarus declared including the creation of a ‘tent city’ in the itself a republic in 1918 before becoming part capital Minsk, were crushed. of the Soviet Union in 1922. Its current borders were established after World War II when Under the policy of ‘market socialism’ Belarus was occupied by the Nazis from 1941- Lukashenka has reversed privatisation and 44 and over 2 million of its people, including imposed controls on prices and currency most of the Jewish population, perished. rates. Although the economy has grown and trade with European countries has increased, Belarus achieved independence from the there is minimal foreign investment and the Soviet Union on 25 August 1991. However private sector is virtually non-existent. In 2005 it retained closer political and economic ties unemployment was officially listed at only 1.6% to Russia than any of the other former Soviet of a workforce of 4.3 million. -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2004 2009 Session document 13.9.2004 B6-0053/2004 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION further to the Commission statement pursuant to Rule 103(2) of the Rules of Procedure by Konrad Krzysztof Szymański, Rolandas Pavilionis and Anna Elzbieta Fotyga on behalf of the Union for Europe of the Nations Group on Belarus RE\541355EN.doc PE 347.467 EN EN B6-0053/2004 European Parliament resolution on Belarus The European Parliament, – having regard to the forthcoming elections and referendum on further extending the Presidential term of office in Belarus, – having regard to the resolutions adopted by the UN Commission on Human Rights on Belarus in April 2003 and 2004 and the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly's Resolution No 1371/2004 on disappeared persons, – having regard to the decision of the UN Commission on Human Rights to appoint a special rapporteur on the situation in Belarus, – having regard to Rule 103(2) of the Rules of Procedure, A. whereas the situation as regards human rights, citizens’ rights and fundamental freedoms has reached a critical stage in Belarus, B. whereas the Belarusian authorities continue to demonstrate their unwillingness to tolerate any form of political opposition, C. alarmed at the numerous cases of opposition activists and independent journalists being detained, imprisoned, fined and expelled from universities, D. concerned at the continuing repression of the independent media and NGOs, E. deeply concerned at the reports of 'disappeared' persons in Belarus, 1. Calls on the Belarusian authorities to immediately guarantee the holding of free and fair elections by inviting the representatives of the opposition parties to play a full role as members and observers at every level of the work of electoral commissions; 2. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

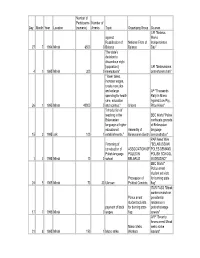

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

General Conclusions and Basic Tendencies 1. System of Human Rights Violations

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND BASIC TENDENCIES 1. SYSTEM OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS The year 2003 was marked by deterioration of the human rights situation in Belarus. While the general human rights situation in the country did not improve, in its certain spheres it significantly changed for the worse. Disrespect for and regular violations of the basic constitutional civic rights became an unavoidable and permanent factor of the Belarusian reality. In 2003 the Belarusian authorities did not even hide their intention to maximally limit the freedom of speech, freedom of association, religious freedom, and human rights in general. These intentions of the ruling regime were declared publicly. It was a conscious and open choice of the state bodies constituting one of the strategic elements of their policy. This political process became most visible in formation and forced intrusion of state ideology upon the citizens. Even leaving aside the question of the ideology contents, the very existence of an ideology, compulsory for all citizens of the country, imposed through propaganda media and educational establishments, and fraught with punitive sanctions for any deviation from it, is a phenomenon, incompatible with the fundamental human right to have a personal opinion. Thus, the state policy of the ruling government aims to create ideological grounds for consistent undermining of civic freedoms in Belarus. The new ideology is introduced despite the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus which puts a direct ban on that. -

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus Geraldine Fagan Abstract: Few are aware that prominent figures in the Belarusian opposition movement are motivated by Christian conviction. In this article, the author trac- es how President Alexander Lukashenko’s restriction of religious freedom has prompted Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants to turn toward democratic activ- ism; it also discusses their rediscovery of religious freedom as a long-standing core value of Belarusian identity. The author’s findings draw on interviews con- ducted in Minsk in the aftermath of the December 2010 presidential election, including those with Christian opposition activists who were subsequently jailed. Keywords: Belarus, democracy, freedom, religion nce a dictatorial regime has muzzled civil society’s more cantankerous O elements—rival political parties and the independent media—a stage is reached at which faith groups, even if falteringly, join the vanguard in the struggle for freedom and justice. In 1980s Communist Poland, the Catholic Church offered a vital moral platform for mass dissent by the Solidarity movement. Prayer meetings at a Leipzig Lutheran church formed the nucleus of protest by hundreds of thousands of East Germans in the weeks before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Might faith-inspired opposition similarly prove a catalyst for political change in Belarus, dubbed “the last true dictatorship in the center of Europe” by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2005?1 The prospects Geraldine Fagan is a 2010–2011 Joseph R. Crapa Fellow at the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. She has monitored religious freedom in Belarus since 2003 as the Moscow correspondent for Forum 18 News Service. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Monitoring Report on Developments in Belarus October 2008 - February 2009

MONITORING REPORT ON DEVELOPMENTS IN BELARUS OCTOBER 2008 - FEBRUARY 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the six-month EU-Belarus dialogue period draws to a close, this monitoring report has been prepared by Belarusian civil society organisations and their international partners 1 to ensure that detailed information regarding the actual situation on the ground in Belarus is available to decision makers reviewing the EU decision on suspending sanctions for Belarus. The report draws the following conclusions: • The steps taken by the Belarusian authorities during this dialogue period have been primarily cosmetic and are ultimately reversible; the process has been neither systematic nor institutionalized. While a small number of organizations have benefited, little has been done to facilitate the functioning of independent civic and media sectors in any meaningful manner. • The minor changes have not addressed the core problems facing civil society in Belarus today. On-going restrictions on human rights and fundamental freedoms continue to cause concern and demonstrate that Belarus has not yet begun a meaningful democratization process. In particular, the authorities’ repression against young political and civic activists, as well as religious minorities, continues unabated. But rather than creating more political prisoners, more subtle forms of repression, including forced military service and “restricted freedom” (house arrest) are increasingly being utilized to control civic and political activists. • While the recent steps by the Belarusian government -

Belarus 50 Days After: Facts, Moods, Forecast

ЦЭНТАР ПАЛІТЫЧНАЙ АДУКАЦЫІ CENTER FOR POLITICAL EDUCATION Miensk, Republic of Belarus Е-mail: [email protected] Gutta cavat lapidem Belarus 50 days after: Facts, moods, forecast I. Introduction: This analysis has been prepared by the Andrei Liakhovich of the Minsk-based Center for Political Education for the purpose of the Slovak-Belarus Task Force analyzing the current political developments of the authorities, the political opposition and society of Belarus 50 days after the referendum. The overall objective of the Slovak-Belarus Task Force is to establish a framework for Slovak know-how transfer to Belarus on key aspects of civil society development. The project seeks to assist civil society in Belarus in preparation for the upcoming presidential elections scheduled for 2006 and further integrate think tanks within civil society in Belarus by linking their expertise and capacity with Belarusian NGOs through the Task Force. II. Summary: One can characterized the post-referendum political situation in Belarus as Lukashenka`s positions was strengthened (since the referendum was unchallenged both by domestic forces and international community compare to Ukraine) and by crisis of the opposition. However, first time there are preconditions for overcoming inter-coalition and inter-party contradictions paralyzing the opposition for a long period. Nevertheless, even in this case the opposition needs stronger international attention for preventing Lukashenka getting elected in 2006. The nature of political development of Belarus will to a greater extend (also first time) depend not on he administration, but on how fast the opposition will able to form an effective coalition, as well as on the efficiency of the Belarus policy of the European Union and the United States. -

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou Et Al

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou et al. Capital: Minsk Population: 9.5 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$14,460 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’sWorld Development Indicators 2013. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Electoral Process 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 Civil Society 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 Independent Media 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance* 6.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Local Democratic Governance n/a 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 Corruption 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 Democracy Score 6.54 6.64 6.71 6.68 6.71 6.57 6.50 6.57 6.68 6.71 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Peaceful Assembly; Fair Trial; Torture, Ill-Tre

Belarus1 IHF FOCUS: freedom of expression and the media; freedom of association; peaceful assembly; fair trial; torture, ill-treatment and police misconduct; prison conditions; death penalty and disappearances; religious intolerance; conscientious objection; ethnicity; intolerance and hate speech. Belarus’ human rights record remained one of the worst in Europe, with the almost complete absence of democracy and the rule of law. High officials who had come to power by undemocratic means showed little respect for the law, and kept in motion a vicious cycle that made the situation of people living in Belarus insecure and unstable. Continued violations of political, social and economic rights created an atmosphere of fear: according to public opinion polls, almost one third of the Belarusian population were contemplating leaving the country and settling abroad. Meanwhile, Belarus faced increasing international isolation. On October 29, the last foreign staff member of the OSCE Advisory and Monitoring Group in Minsk - the officer-in-charge - left the country after the Belarusian government had refused to extend her diplomatic accreditation. Prior to that, the Belarusian authorities had successively expelled OSCE mission members while at the same time making it impossible for the mission to operate normally.2 There were almost no state institutions in Belarus whose officials were elected or appointed according to democratic procedure: most of them were appointed directly by President Aleksandr Lukashenka or his administration. As a result of non-observance of the rule of law, the power of officials increased. The Criminal Code and legislation governing economic activities allowed arbitrary accusations to be made against any person of various forms of violations and this was used to intimidate critically- minded officials and to manipulate them.