A History of the Cigar Factory Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATE of NEW JERSEY APPLICATION for REGISTRATION of EXEMPT CIGAR BAR OR CIGAR LOUNGE (Pursuant to N.J.S.A

STATE OF NEW JERSEY APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF EXEMPT CIGAR BAR OR CIGAR LOUNGE (Pursuant to N.J.S.A. 26:3D-55 et seq. and N.J.A.C. 8:6) INSTRUCTIONS This form is to be used to apply for the exemption of certain cigar bars and cigar lounges from the New Jersey Smoke- Free Air Act, N.J.S.A. 26:3D-55 et seq. Applicants must submit Section 1 and 2. Section 1 is to be completed by the applicant. Section 2 must be completed by a New Jersey licensed Certified Public Accountant. If the proposed exempt cigar bar or cigar lounge is located within another establishment at which smoking is prohibited pursuant to N.J.S.A. 26:3D-55 et seq., the applicant must also submit Section 3. Section 3 must be completed by New Jersey Registered Architect or a New Jersey Licensed Professional Engineer. The applicant must submit the completed forms to the local health agency with jurisdiction over the municipality in which the establishment is located. The local health agency will not process an incomplete application. Following are definitions of words and terms used in Section 1 pursuant to N.J.S.A. 26:3D-55 et seq. and N.J.A.C. 8:6: “Backstream” means recirculate, as that term is defined in the mechanical subcode of the New Jersey State Uniform Construction Code at N.J.A.C. 5:23-3.20. “Cigar bar” means any bar, or area within a bar, designated specifically for the smoking of tobacco products, purchased on the premises or elsewhere; except that a cigar bar that is in an area within a bar shall be an area enclosed by solid walls or windows, a ceiling and a solid door and equipped with a ventilation system which is separately exhausted from the nonsmoking areas of the bar so that air from the smoking area is not recirculated to the nonsmoking areas and smoke is not backstreamed into the nonsmoking areas. -

The Cigar That Sparked a Revolution

Sunland Tribune Volume 6 Article 5 1980 The Cigar That Sparked A Revolution Tony Pizzo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Pizzo, Tony (1980) "The Cigar That Sparked A Revolution," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 6 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol6/iss1/5 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pizzo: The Cigar That Sparked A Revolution THE CIGAR THAT SPARKED A REVOLUTION By TONY PIZZO CIGAR OF LIBERTY The “Cigar of Liberty” made in Tampa carried the “Message to Gomez” that sparked the flames of revolution. For years, this cigar stood as the symbol of friendship and goodwill between Tampa and Cuba. - Sketch by Rodolpho Pena Mora Millions of Tampa cigars have gone out into the world as ambassadors-of-good-will to be smoked into puffs of fantasies, but the most famous cigar ever rolled in Tampa went out, not as a Corona or a Queen, but as a liberator to spark the Cuban Revolution of 1895. This cigar cost thousands of lives, but won independence for Cuba. American school children, when studying the Spanish-American War, learn about "A Message to Garcia," but the school children of Cuba, when studying the history of the Cuban Insurrection of 1895, are taught of a more important message: "A Message to Gomez." FEBRUARY 24, 1895, the date picked by the Cu ban conspirators in Havana to launch the "War Cry - Viva Cuba Libre. -

Cohiba: Not Just Another Name, Not Just Another Stogie: Does General Cigar Own a Valid Trademark for the Name Cohiba in the United States

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 21 Number 4 Article 4 8-1-1999 Cohiba: Not Just Another Name, Not Just Another Stogie: Does General Cigar Own a Valid Trademark for the Name Cohiba in the United States Mark D. Nielsen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Nielsen, Cohiba: Not Just Another Name, Not Just Another Stogie: Does General Cigar Own a Valid Trademark for the Name Cohiba in the United States, 21 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 633 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol21/iss4/4 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COHIBA: NOT JUST ANOTHER NAME, NOT JUST ANOTHER STOGIE: DOES GENERAL CIGAR OWN A VALID TRADEMARK FOR THE NAME "COHIBA" IN THE UNITED STATES? I. INTRODUCTION Cuban Cohiba cigars are widely regarded as the world's finest cigars. Crafted from the "selection of the selection" of Cuba's tobacco,1 cigar aficionados2 clamor for the opportunity to enjoy Cohibas. Cohiba cigars are not, and have never been, legally available in the United States because the economic embargo against Cuba 3 took effect prior to the creation of Cohiba by Avelino Lara in 1968. -

Catalog Cigar 2

Cohiba, Fidel Castros preferred brand, was created in 1966 as Havanas premier brand for diplomatic purposes. Since 1982, it was offered to the public in three sizes: Lanceros, Coronas Especiales and Panetelas. In 1989, three more sizes were added to complete the classic line namely: Esplendidos, Robustos and Exquisitos. In 1992, the following five sizes were further made in order to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the discovery of Cuba in 1492: Siglo I, II, III, IV and V. Name Lenght Ring Box Price BEHIKE 54 10 144 mm 54 10 28.958.000 VNĐ ESPLENDIDOS 25 178 mm 47 25 41.699.000 VNĐ EXQUISITOS 25 125 mm 33 25 14.157.000 VNĐ MEDIO SIGLO 25 102 mm 52 25 21.030.000 VNĐ PIRAMIDES EXTRA 10 160 mm 54 10 15.316.000 VNĐ PIRAMIDES EXTRA AT 15 160 mm 54 AT 15 28.314.000 VNĐ ROBUSTOS 25 124 mm 50 25 24.145.000 VNĐ ROBUSTOS 15 124 mm 50 AT 15 14.492.000 VNĐ MADURO SECRETOS 10 110 mm 40 10 5.869.000 VNĐ MADURO SECRETOS 25 110 mm 40 25 14.672.000 VNĐ SIGLO I 25 102 mm 40 25 10.940.000 VNĐ SIGLO I AT 15 102 mm 40 AT 15 9.266.000 VNĐ Name Lenght Ring Box Price SIGLO II 25 129 mm 42 CP 25 16.731.000 VNĐ SIGLO II 25 129 mm 42 25 16.731.000 VNĐ SIGLO III 25 155 mm 42 CP 25 20.798.000 VNĐ SIGLO IV 25 143 mm 46 25 25.225.000 VNĐ SIGLO IV 15 143 mm 46 AT 15 18.147.000 VNĐ SIGLO IV 25 143 mm 46 25 25.225.000 VNĐ SIGLO VI TUBOS 15 150 mm 52 AT 15 26.435.000 VNĐ SIGLO VI 25 150 mm 52 25 37.323.000 VNĐ TALISMAN 10 2017 LIMITED 154 mm 54 10 30.888.000 VNĐ Lenght 156 mm Lenght 124 mm Ring 52 mm Ring 50 mm Box Box COMBINACIONES SELECCION PIRAMIDES, 6'S COMBINACIONES SELECCION ROBUSTOS 6'S Romeo y Julieta, Cohiba, Hoyo de Monterrey, Cohiba Robusto, Montecristo Open Master, The Montecristo No. -

Cigar: Cigarillos

WHAT is a CIGAR? What is a cigar? A cigar is a roll of fermented tobacco wrapped either in tobacco leaf or paper that contains tobacco or tobacco extract. Large (Premium) Cigar: Tobacco tightly rolled in dried tobacco leaves that is handmade and sells for at least $2 per cigar. These cigars can be more than 7 inches in length, and typically contain between 5 and 20 grams of tobacco. Some premium cigars contain the tobacco equivalent of an entire pack of cigarettes, and can take between 1 and 2 hours to smoke.1 Cigarillos or Small Cigars: Tobacco wrapped in dried tobacco leaf or in any substance containing tobacco. These products are shorter and narrower than large cigars and contain about 3 grams of tobacco.1 They are available with or without a filter tip. Cigarillo/Small Cigar products are available in a variety of fruit and candy flavors and can often be purchased individually or in small ‘packs’ of five or less. Popular brands include Black & Mild, Swisher Sweets, White Owl and Phillies Cigarillos. These products are attractive, affordable, and attainable to youth. 1 NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE. Cigar Smoking and Cancer. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Tobacco/cigars Maryland Department of 10-12 Health and Mental Hygiene Little Cigars (Or Brown Cigarettes): Little Cigars are nearly identical in size and appearance to cigarettes. The tobacco is wrapped in brown paper that contains some tobacco leaf (typically powdered tobacco leaf). Little cigars are available in a variety of flavors and - just like cigarettes - are sold in packs of 20. -

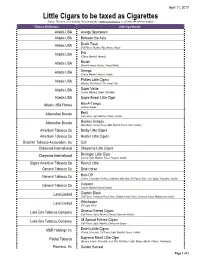

Little Cigars to Be Taxed As Cigarettes (Notice: This List Is Not All Inclusive

April 11, 2017 Little Cigars to be taxed as Cigarettes (Notice: This list is not all inclusive. Visit our website at www.mt.gov/revenue or call (406) 444-6900 for updates) Tobacco Distributors Little Cigar Brands Altadis USA Arango Sportsmen Altadis USA Between the Acts Altadis USA Dutch Treat (Full Flavor, Menthol, Pipe Aroma, Sweet) Altadis USA Erik (Cherry, Menthol, Natural) Altadis USA Muriel (Black N Sweet, Menthol, Sweet N Mild) Altadis USA Omega (Cherry, Menthol, Natural, Sweet) Altadis USA Phillies Little Cigars (Menthol 100, Natural 100, Sweet 100) Altadis USA Super Value (Cherry, Menthol, Sweet, Ultra Mild) Altadis USA Supre Sweet Little Cigar Altadis USA Florida Hav-A-Tampa (Natural, Sweet) Alternative Brands Boaz (Full Flavor, Light, Menthol, Cherry, Vanilla) Alternative Brands Havana Honeys (Blackberry, Cherry, Honey, Mint, Natural, Peach, Rum, Vanilla) American Tobacco Co Derby Little Cigars American Tobacco Co Hustler Little Cigars Brazilian Tobacco Association, Inc Colt Cheyenne International Cheyenne Little Cigars Cheyenne International Derringer Little Cigar (Cherry, Light, Menthol, Peach, Regular, Vanilla) Cigars American Tobacco Co Recruit Little General Tobacco Co Dark Horse General Tobacco Co Hats Off (Cherry, Chocolate, Full Flavor, Menthol, Mild, Mild 100, Peach, Rum, Sour Apple, Strawberry, Vanilla) General Tobacco Co Vaquero (Cherry, Menthol Natural Vanilla) Lane Limited Captain Black (Full Flavor, Caribbean Peach Rum, Tahitian Sweet Cherry, Jamaican Sweet, Madagascar Vanilla) Lane Limited Winchester (FF, Light -

Little Cigars, Cigarillos, and Cigars

Little Cigars, Cigarillos, and Cigars: A Guide for Local Communities Prepared by: The Association for Nonsmokers-Minnesota 2395 University Avenue West, Suite 310 Saint Paul, MN 55114 www.ansrmn.org 651.646.3005 1 Executive summary The Ramsey Tobacco Coalition, a program of the Association for Nonsmokers-MN (ANSR), works to reduce youth access to tobacco throughout communities in Ramsey County. Because youth are price sensitive, a proven youth tobacco prevention strategy is to make it harder for youth to obtain tobacco products by increasing their price. This is especially true for little cigars and cigarillos. These sweet, flavored tobacco products are much less expensive than cigarettes, in part because they are sold individually. These products are heavily promoted to youth and, as a result, are popular with them. According the Minnesota Department of Health, 40% of Minnesota high school students report that they have tried cigars. Communities can help prevent youth from becoming addicted to cigars by regulating the sale of these harmful products at the local level. The cigars of today The cigar market has changed. Unlike the large stogies of the past, the newest generation of cigars is cheap, flavored, and smaller in size. The rapidly growing availability of these cheap cigars caused the sale of cigars to double in the U.S. from 2000 to 2012.1 Today, cigars are available in numerous flavors, sizes, and price points making them appealing and accessible to youth. Flavoring. Cigars are available in many flavors such as: chocolate, ba boom strawberry kiwi, grape, watermelon, and pineapple. Size. Cigars are sold in a number of sizes and go by different names such as: cigar, cigarillo, blunt, and little cigar. -

Cigars, Little Cigars, and 3

the truth about little cigars, cigarillos & cigars BACKGROUND • Cigars are defined in the United States (U.S.) tax code as “any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or in any substance containing tobacco” that does not meet the definition of a cigarette.1 • However, despite those definitions, cigars are a heterogeneous product category, with at least three major cigar products—little cigars, cigarillos and large cigars.2 • Little Cigars (aka small cigars) weigh less than 3 lbs/1000 and resemble cigarettes.3 Cigarettes are wrapped in white paper, CIGARETTE while little cigars are wrapped in brown paper that contains some tobacco leaf. Generally, little cigars have a filter like a LITTLE CIGAR cigarette.4 • Cigarillos weigh more than 3 lbs/1000 and are classified as “large” cigars by federal tax code.2 Cigarillos are longer, slimmer versions of large cigars. Cigarillos do not CIGARILLO (TIPPED AND UNTIPPED) usually have a filter, but sometimes have wood or plastic tips.2 • Traditional (aka large cigars) weigh more than 3 pounds/10002 and are also referred CIGAR to as “stogies.” • Little cigars, cigarillos, and large cigars are offered in a variety of flavors including candy and fruit flavors such as sour apple, cherry, grape, chocolate and menthol.5,6 • Until recently, cigars were not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, in May 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finalized its “deeming” regulation, extending its authority to little cigars, cigarillos, and premium cigars, as well as to components and parts such as rolling papers and filters. This authority does not extend to accessories such as lighters and cutters.7 This means that FDA can now issue product standards to make all cigars less appealing, toxic and addictive, and it can issue marketing restrictions like those in place for cigarettes, in order to keep cigars out of the hands of kids. -

CIGAR AFICIONADO GROUPS ONLY 2018 IF YOU HAVE the GROUP, WE 4 Nights/5 Days from $2,479 Havana HAVE the SPACE! Thursday Arrivals

Large Group Program CIGAR AFICIONADO GROUPS ONLY 2018 IF YOU HAVE THE GROUP, WE 4 Nights/5 Days FROM $2,479 Havana HAVE THE SPACE! Thursday Arrivals Traditional manufacture of cigars at the cuban tobacco factory ESCORTED PEOPLE-TO-PEOPLE PROGRAM PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS (4) Havana •Live the adventure of your dreams in Cuba with special focus on the country’s world- renowned cigars •Explore a working tobacco plantation and see up-close the entire tobacco cultivating process in the Viñales Valley’s Pinar del Rio• •Visit the Partagás cigar factory built in 1845 and FLORIDA La Corona cigar factory •Participate in a workshop on “Cigar and Wine Pairing” in Cojimar at the paladar Café Ajiaco •See up-close how the world’s acclaimed Cuban cigars are at a Cigar Rolling Workshop at Casa de La Amistad Havana DAY 1 THU HAVANA 4 CUBA I I Upon your arrival in Havana you will be met by your professional, English speaking tour director to embark on your hands-on exploration of Cuba focused on experiencing this legendary cigar producing land and its people. Take-in the tropical views and classic American cars all around as you stop in Revolution Square to see the immense images of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos that adorn the surrounding edifices. Your people-to-people interactions begin right away with a lunch in old Havana at a privately-owned restaurant serving homemade farm-to-table Cuban dishes called a - No. of Overnight Stays # “paladar.” After lunch, head to your hotel for check-in and enjoy some time to settle into your room before meeting for a welcome drink with appetizers and a program briefing with your group. -

Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 17, No. 2 (2005)

From handcrafted tobacco rolls to machine-made cigarettes: The transformation and Americanization of Puerto Rican tobacco, 1847-1903 Paper for the VIII Congress of the Asociación Española de Historia Económica, Santiago de Compostela, 13-16 September 2005. Juan José Baldrich Professor Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Puerto Rico 23345 UPR Station Río Piedras, Puerto Rico 00931-3345 Telephones: (787) 764-0000 ext. 4311 and 3105 E-mail [email protected] Abstract The Puerto Rican tobacco industry experienced a profound transformation from the middle of the nineteenth century to the U.S. invasion in 1898 that can be explained around three dimensions. First, growers started to harvest a leaf that resembled more Cuban leaf for cigars rather than the one used for cut tobacco or rolls to be consumed by chewing. Second, factories relying on wage labor replaced small artisanal shops operated by independent cigar or cigarette makers. This industrial capacity was not export oriented, thus contributing to the substitution of Havana cigars and Cuban cigarettes with domestic ones. Third, the development of an entrepreneurial class in tobacco manufacture came to a halt as a consequence of the invasion. At the turn of the century, the American Tobacco Company, the “trust,” bought into the most technologically sophisticated . An earlier version of this paper is forthcoming from CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 17, no. 2 (2005). The author acknowledges the advice and suggestions of Jean Stubbs, Humberto García, the late Andrés Ramos Mattei, and the research assistance of Lynnette Rivera and Miriam Lugo Colón. -

Basic Survival Skills for Aviation

OK-06-033 BASIC SURVIVAL SKILLS FOR AVIATION OFFICE OF AEROSPACE MEDICINE CIVIL AEROSPACE MEDICAL INSTITUTE AEROMEDICAL EDUCATION DIVISION INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI). CAMI is part of the FAA’s Office of Aerospace Medicine (OAM). As an integral part of the OAM mission, CAMI has several responsibilities. One responsi- bility tasked to CAMI’s Aerospace Medical Education Division is to assure safety and promote aviation excellence through aeromedical education. To help ensure that this mission becomes reality, the Aerospace Medical Edu- cation Division, through the Airman Education Programs, established a one day post-crash survival course. This course is designed as an introduction to survival, providing the basic knowledge and skills for coping with various survival situations and environments. If your desire is to participate in a more extensive course than ours you will find many highly qualified alternatives, quite possibly in your local area. Because no two survival episodes are identical, there is no "PAT" answer to any one-survival question. Your instructors have extensive back- ground and training, and have conducted basic survival training for the mili- tary. If you have any questions on survival, please ask. If we don't have the answer, we will find one for you. Upon completion, you will have an opportunity to critique the course. Please take the opportunity to provide us with your thoughts con- cerning the course, instructors, training aids. This will be your best opportu- nity to express your opinion on how we might improve this course. Enjoy the course. 1 NOTES CIVIL AEROSPACE MEDICAL INSTITUTE _____________________________________________________ Director: Melchor J. -

Cigars: an Interesting Overview I Must Admit I Have Smoked a Few Cigars, but Never Really Liked Them

Cigars: An Interesting Overview I must admit I have smoked a few cigars, but never really liked them. I have a neighbor who smokes them semi‐ regularly; a friend who chews on them (Swisher Sweets), but never smokes them; and another friend, one who claims that his cigar use has had personal health benefits, such as reducing colds. He never chews or smokes it but keeps it in his mouth for some time. Well, why an article on cigars? It was a trip to the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, Florida and talking with the docent that helped make this article happen. It is also attributed to my friends and a relative. Cigars have been around for thousands of years. Central American Mayans (Guatemala or the Mexican Yucatan) in or before the 10th century were the first to use tobacco in the form of a rudimentary cigar by wrapping tobacco in either palm or plantain leaves. "The name ‘cigar’ possibly derives from the Mayan word ‘sicar,’ meaning to smoke rolled tobacco leaves." <cigaraficionado.com> <holts.com> There were reports of Christopher Columbus being offered dried tobacco in 1492 in Cuba from the Taino natives. Sailors who brought it back to Europe started growing the plants. Smoking became popular in Spain and Portugal. In the late 1500s a Spanish doctor claimed that tobacco had medicinal potential. The popularity of tobacco was seen during the 1600s when it was even used as money. <cigaraficionado.com> <finckcigarcompany.com> <academicudayton.edu> <holts.com> Tobacco is, of course, the root of the cigar experience and The Boston University Medical Center in a community outreach information on the history of tobacco wrote: "Tobacco is a plant that grows natively in North and South America.