Kolb on Cavelos, 'The Science of Star Wars'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUGBOAT Volume 26, Number 1 / 2005 Practical

TUGBOAT Volume 26, Number 1 / 2005 Practical TEX 2005 Conference Proceedings General Delivery 3 Karl Berry / From the president 3 Barbara Beeton / Editorial comments Old TUGboat issues go electronic; CTAN anouncement archives; Another LATEX manual — for word processor users; Create your own alphabet; Type design exhibition “Letras Latinas”; The cost of a bad proofreader; Looking at the same text in different ways: CSS on the web; Some comments on mathematical typesetting 5 Barbara Beeton / Hyphenation exception log A L TEX 7 Pedro Quaresma / Stacks in TEX Graphics 10 Denis Roegel / Kissing circles: A French romance in MetaPost Software & Tools 17 Tristan Miller / Using the RPM package manager for (LA)TEX packages Practical TEX 2005 29 Conference program, delegates, and sponsors 31 Peter Flom and Tristan Miller / Impressions from PracTEX’05 Keynote 33 Nelson Beebe / The design of TEX and METAFONT: A retrospective Talks 52 Peter Flom / ALATEX fledgling struggles to take flight 56 Anita Schwartz / The art of LATEX problem solving 59 Klaus H¨oppner / Strategies for including graphics in LATEX documents 63 Joseph Hogg / Making a booklet 66 Peter Flynn / LATEX on the Web 68 Andrew Mertz and William Slough / Beamer by example 74 Kaveh Bazargan / Batch Commander: A graphical user interface for TEX 81 David Ignat / Word to LATEX for a large, multi-author scientific paper 85 Tristan Miller / Biblet: A portable BIBTEX bibliography style for generating highly customizable XHTML 97 Abstracts (Allen, Burt, Fehd, Gurari, Janc, Kew, Peter) News 99 Calendar TUG Business 104 Institutional members Advertisements 104 TEX consulting and production services 101 Silmaril Consultants 101 Joe Hogg 101 Carleton Production Centre 102 Personal TEX, Inc. -

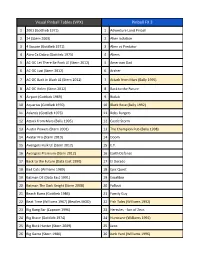

Pinball Game List

Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 1 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) 1 Adventure Land Pinball 2 24 (Stern 2009) 2 Alien Isolation 3 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) 3 Alien vs Predator 4 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) 4 Aliens 5 AC-DC Let There Be Rock LE (Stern 2012) 5 American Dad 6 AC-DC Luci (Stern 2012) 6 Archer 7 AC-DC Back in Black LE (Stern 2012) 7 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 8 AC-DC Helen (Stern 2012) 8 Back to the Future 9 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) 9 Biolab 10 Aquarius (Gottlieb 1970) 10 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 11 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 11 Bobs Burgers 12 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 12 Castle Storm 13 Austin Powers (Stern 2001) 13 The Champion Pub (Bally 1998) 14 Avatar Pro (Stern 2010) 14 Doom 15 Avengers Hulk LE (Stern 2012) 15 E.T. 16 Avengers Premium (Stern 2012) 16 Earth Defense 17 Back to the Future (Data East 1990) 17 El Dorado 18 Bad Cats (Williams 1989) 18 Epic Quest 19 Batman DE (Data East 1991) 19 Excalibur 20 Batman The Dark Knight (Stern 2008) 20 Fallout 21 Beach Bums (Gottlieb 1986) 21 Family Guy 22 Beat Time (Williams 1967) (Beatles MOD) 22 Fish Tales (Williams 1992) 23 Big Bang Bar (Capcom 1996) 23 Hercules - Son of Zeus 24 Big Brave (Gottlieb 1974) 24 Hurricane (Williams 1991) 25 Big Buck Hunter (Stern 2009) 25 Jaws 26 Big Game (Stern 1980) 26 Junk Yard (Williams 1996) Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 27 Big Guns (Williams 1987) 27 Jurassic Park 28 Black Knight (Williams 1980) 28 Jurassic Park Pinball Mayhem 29 Black Knight 2000 (Williams 1989) 29 Jurassic World 30 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 30 Mars 31 Blue Note (Gottlieb 1979) 31 Marvel - Age of Ultron 32 Bram Stoker's Dracula (Williams 1993) 32 Marvel - Ant-Man 33 Bronco (Gottlieb 1977) 33 Marvel - Blade 34 Bubba the Redneck Werewolf (2018) 34 Marvel - Captain America 35 Buccaneer (Gottlieb 1976) 35 Marvel - Civil War 36 Buckaroo (Gottlieb 1965) 36 Marvel - Deadpool 37 Bugs Bunny B. -

Any Gods out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 2 October 2003 Article 3 October 2003 Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek John S. Schultes Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Schultes, John S. (2003) "Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek Abstract Hollywood films and eligionr have an ongoing rocky relationship, especially in the realm of science fiction. A brief comparison study of the two giants of mainstream sci-fi, Star Wars and Star Trek reveals the differing attitudes toward religion expressed in the genre. Star Trek presents an evolving perspective, from critical secular humanism to begrudging personalized faith, while Star Wars presents an ambiguous mythological foundation for mystical experience that is in more ways universal. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 Schultes: Any Gods Out There? Science Fiction has come of age in the 21st century. From its humble beginnings, "Sci- Fi" has been used to express the desires and dreams of those generations who looked up at the stars and imagined life on other planets and space travel, those who actually saw the beginning of the space age, and those who still dare to imagine a universe with wonders beyond what we have today. -

18Th International Conference on General

18TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON GENERAL RELATIVITY AND GRAVITATION (GRG18) 8 – 13 July 2007 7TH EDOARDO AMALDI CONFERENCE ON GRAVITATIONAL WAVES (AMALDI7) www.grg18.com 8 – 14 July 2007 www.Amaldi7.com Sydney Convention & Exhibition Centre • Darling Harbour • Sydney Australia INSPIRALLING BLACK HOLES RAPID EPANSION OF AN UNSTABLE NEUTRON STAR Credit: Seidel (LSU/AEI) / Kaehler (ZIB) Credit: Rezzolla (AEI) / Benger (ZIB) GRAZING COLLISION OF TWO BLACK HOLES VISUALISATION OF A GRAVITATIONAL WAVE HAVING Credit: Seidel (AEI) / Benger (ZIB) TEUKOLSKY'S SOLUTION AS INITIAL DATA Credit: Seidel (AEI) / Benger (ZIB) ROLLER COASTER DISTORTED BY SPECIAL RELATIVISTIC EFFECTS Credit: Michael Hush, Department of Physics, The Australian National University The program for GRG18 will incorporate all areas of General Relativity and Gravitation including Classical General Relativity; Numerical Relativity; Relativistic Astrophysics and Cosmology; Experimental Work on Gravity and Quantum Issues in Gravitation. The program for Amaldi7 will cover all aspects of Gravitational Wave Physics and Detection. PLENARY LECTURES Peter Schneider (Bonn) Donald Marolf USA Bernard Schutz Germany Bernd Bruegman (Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena) Gravitational lensing David McClelland Australia Robin Stebbins United States Numerical relativity Daniel Shaddock (JPL California Institute of Technology) Jorge Pullin USA Kimio Tsubono Japan Daniel Eisenstein (University of Arizona) Gravitational wave detection from space: technology challenges Norna Robertson USA Stefano Vitale Italy Dark energy Stan Whitcomb (California Institute of Technology) Misao Sasaki Japan Clifford Will United States Ground-based gravitational wave detection: now and future Bernard F Schutz Germany Francis Everitt (Stanford University) Susan M. Scott Australia LOCAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE Gravity Probe B and precision tests of General Relativity Chair: Susan M. -

How Disney's Abc Avoided Reporting Electronic Arts Star Wars Game Micro

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Major Papers Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2018 HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO-TRANSACTIONS Rohan Khanna University of Windsor, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers Part of the Communication Commons, and the Models and Methods Commons Recommended Citation Khanna, Rohan, "HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO- TRANSACTIONS" (2018). Major Papers. 41. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/41 This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO-TRANSACTIONS by Rohan Khanna A Major Research Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Communication and Social Justice in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2018 © 2018 Rohan Khanna HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO-TRANSACTIONS by Rohan Khanna APPROVED BY: ———————————————— V. Manzerolle Communication, Media, and Film ———————————————— J. P. Winter, Advisor Communication, Media, and Film May 10, 2018 iii AUTHOR’S DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this MRP and that no part of this Major paper has been published or submitted for publication. -

WARGAMES: WHEN HACKING WENT MAINSTREAM Tuesday, September 20, 2011 - 11:40 AM by Alex Goldman / PJ Vogt

WHERE TO LISTEN CONTACT US WARGAMES: WHEN HACKING WENT MAINSTREAM Tuesday, September 20, 2011 - 11:40 AM By Alex Goldman / PJ Vogt Share Tweet 9 Like 0 The concept of hacking entered the American popular imagination through a fairly unlikely medium – the Hollywood blockbuster. Specifically, the 1983 film Wargames, about a high school hacker whose computer tampering nearly starts a nuclear war. Conservative Bloggers Vindicated, Advice When WarGames was released, the way that people used for Leakers, and More computers had just dramatically changed. Computers, which had An 11-year-old and his 3D printer once been solely the province of big research universities, had Who’s gonna pay for this stuff? become small and fast enough to make their way into the homes A Journalistic Civil War Odyssey of hobbyists in the 1970's. WarGames was released during the A New Incentive for Cord Cutters lifespan of the Apple II and the IBM PC 5150, some of the first A Source for Sources truly successful mass marketed home computers. Web Only Audio Extra - TV Cord Cutters (MGM/United Artists) Angelina Jolie's Secret Test Results With IRS Scandal, Conservative Bloggers JOIN THE DISCUSSION [3] Feel Vindicated Brooke Gladstone + Cyndi Lauper WarGames trailer FEEDS On The Media : Latest Episodes (Atom) On The Media : Latest Stories (Atom) On the Media Feed (Atom) hack week Feed (Atom) On The Media Podcast However, when the film was pitched, no one really understood its premise. The script was rejected by numerous studios. According to the filmmakers, one basic problem was that no one knew what genre it fit into – the technology depicted in the movie (for instance, dial-up modems) was so new that studio representatives thought the movie only made sense as science fiction. -

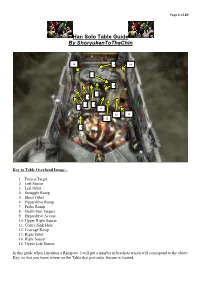

Star Wars: Episode IV – a New Hope Table Guide by Shoryukentothechin

Page 1 of 37 Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope Table Guide By ShoryukenToTheChin 3 5 7 4 6 1 2 8 9 Key to Table Overhead Image – 1. Landspeeder Target/Sink Hole 2. Left Orbit 3. Alliance Ramp 4. Left Jump Ramp 5. Centre Target 6. Right Jump Ramp 7. Cantina Ramp 8. Right Orbit 9. Standalone Target In this guide when I mention a Ramp etc. I will put a number in brackets which will correspond to the above Key, so that you know where on the Table that particular feature is located. Page 2 of 37 TABLE SPECIFICS Notice: This Guide is based on the gameplay of the Zen Pinball 2 (PS4/PS3/Vita) version of the Table on default controls. Some of the controls will be different on the other versions (Pinball FX 2, Star Wars Pinball, etc...), but everything else in the Guide remains the same. INTRODUCTION This Table came about as a result of the partnership between Zen Studios and LucasArts; this license allowed Zen to produce Tables based on the Star Wars License. As of now Zen has been licensed to release 10 Star Wars Themed Tables but with more Tables possible in the future. The third batch of Tables was released in a 4 Pack which include the Tables; Han Solo, Droids, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope & Masters of The Force. This Table is of course the Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope; which is a Table that pays homage to the iconic Film. The Artwork and Audio cues are spot on once again, adding that unique originality to the Table’s Playfield. -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

Han Solo Guide by Shoryukentothechin

Page 1 of 29 Han Solo Table Guide By ShoryukenToTheChin 15 9 10 7 8 6 4 3 5 2 11 13 14 12 1 Key to Table Overhead Image – 1. Frozen Target 2. Left Saucer 3. Left Orbit 4. Smuggle Ramp 5. Shoot Orbit 6. Hyperdrive Ramp 7. Probe Ramp 8. Death Star Targets 9. Hyperdrive Access 10. Upper Right Saucer 11. Centre Sink Hole 12. Courage Ramp 13. Right Orbit 14. Right Saucer 15. Upper Left Saucer In this guide when I mention a Ramp etc. I will put a number in brackets which will correspond to the above Key, so that you know where on the Table that particular feature is located. Page 2 of 29 TABLE SPECIFICS Notice: This Guide is based on the gameplay of the Zen Pinball 2 (PS4/PS3/Vita) version of the Table on default controls. Some of the controls will be different on the other versions (Pinball FX 2, Star Wars Pinball, etc...), but everything else in the Guide remains the same. INTRODUCTION This Table came about as a result of the partnership between Zen Studios and LucasArts; this license allowed Zen to produce Tables based on the Star Wars License. As of now Zen has been licensed to release 10 Star Wars Themed Tables but with more Tables possible in the future. The third batch of Tables was released in a 4 Pack which include the Tables; Han Solo, Droids, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope & Masters of The Force. This Table is of course Han Solo; it pays homage to one of the most iconic Movie characters of all time. -

Package 'Ggsci'

Package ‘ggsci’ May 14, 2018 Type Package Title Scientific Journal and Sci-Fi Themed Color Palettes for 'ggplot2' Version 2.9 Maintainer Nan Xiao <[email protected]> Description A collection of 'ggplot2' color palettes inspired by plots in scientific journals, data visualization libraries, science fiction movies, and TV shows. License GPL-3 | file LICENSE LazyData TRUE VignetteBuilder knitr URL https://nanx.me/ggsci/, https://github.com/road2stat/ggsci BugReports https://github.com/road2stat/ggsci/issues Depends R (>= 3.0.2) Imports grDevices, scales, ggplot2 (>= 2.0.0) Suggests knitr, rmarkdown, gridExtra, reshape2 Encoding UTF-8 RoxygenNote 6.0.1.9000 NeedsCompilation no Author Nan Xiao [aut, cre] (<https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0250-5673>), Miaozhu Li [ctb] Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2018-05-14 04:38:05 UTC R topics documented: ggsci-package . .2 pal_aaas . .4 pal_d3 . .5 1 2 ggsci-package pal_futurama . .5 pal_gsea . .6 pal_igv . .7 pal_jama . .7 pal_jco . .8 pal_lancet . .9 pal_locuszoom . .9 pal_material . 10 pal_nejm . 11 pal_npg . 12 pal_rickandmorty . 12 pal_simpsons . 13 pal_startrek . 14 pal_tron . 14 pal_uchicago . 15 pal_ucscgb . 16 rgb_gsea . 16 rgb_material . 17 scale_color_aaas . 18 scale_color_d3 . 19 scale_color_futurama . 20 scale_color_gsea . 21 scale_color_igv . 22 scale_color_jama . 23 scale_color_jco . 24 scale_color_lancet . 25 scale_color_locuszoom . 26 scale_color_material . 27 scale_color_nejm . 28 scale_color_npg . 29 scale_color_rickandmorty . 30 scale_color_simpsons . 31 scale_color_startrek . 32 scale_color_tron -

The “Tron: Legacy”

Release Date: December 16 Rating: TBC Run time: TBC rom Walt Disney Pictures comes “TRON: Legacy,” a high-tech adventure set in a digital world that is unlike anything ever captured on the big screen. Directed by F Joseph Kosinski, “TRON: Legacy” stars Jeff Bridges, Garrett Hedlund, Olivia Wilde, Bruce Boxleitner, James Frain, Beau Garrett and Michael Sheen and is produced by Sean Bailey, Jeffrey Silver and Steven Lisberger, with Donald Kushner serving as executive producer, and Justin Springer and Steve Gaub co-producing. The “TRON: Legacy” screenplay was written by Edward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz; story by Edward Kitsis & Adam Horowitz and Brian Klugman & Lee Sternthal; based on characters created by Steven Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird. Presented in Disney Digital 3D™, Real D 3D and IMAX® 3D and scored by Grammy® Award–winning electronic music duo Daft Punk, “TRON: Legacy” features cutting-edge, state-of-the-art technology, effects and set design that bring to life an epic adventure coursing across a digital grid that is as fascinating and wondrous as it is beyond imagination. At the epicenter of the adventure is a father-son story that resonates as much on the Grid as it does in the real world: Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund), a rebellious 27-year-old, is haunted by the mysterious disappearance of his father, Kevin Flynn (Oscar® and Golden Globe® winner Jeff Bridges), a man once known as the world’s leading tech visionary. When Sam investigates a strange signal sent from the old Flynn’s Arcade—a signal that could only come from his father—he finds himself pulled into a digital grid where Kevin has been trapped for 20 years. -

The Walt Disney Company: a Corporate Strategy Analysis

The Walt Disney Company: A Corporate Strategy Analysis November 2012 Written by Carlos Carillo, Jeremy Crumley, Kendree Thieringer and Jeffrey S. Harrison at the Robins School of Business, University of Richmond. Copyright © Jeffrey S. Harrison. This case was written for the purpose of classroom discussion. It is not to be duplicated or cited in any form without the copyright holder’s express permission. For permission to reproduce or cite this case, contact Jeff Harrison at [email protected]. In your message, state your name, affiliation and the intended use of the case. Permission for classroom use will be granted free of charge. Other cases are available at: http://robins.richmond.edu/centers/case-network.html "Walt was never afraid to dream. That song from Pinocchio, 'When You Wish Upon a Star,' is the perfect summary of Walt's approach to life: dream big dreams, even hopelessly impossible dreams, because they really can come true. Sure, it takes work, focus and perseverance. But anything is possible. Walt proved it with the impossible things he accomplished."1 It is well documented that Walt Disney had big dreams and made several large gambles to propel his visions. From the creation of Steamboat Willie in 1928 to the first color feature film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves” in 1937, and the creation of Disneyland in Anaheim, CA during the 1950’s, Disney risked his personal assets as well as his studio to build a reality from his dreams. While Walt Disney passed away in the mid 1960’s, his quote, “If you can dream it, you can do it,”2 still resonates in the corporate world and operations of The Walt Disney Company.