Domestic Antecedents of Afghan Policy 65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Conference Program

CONFERENCE PROGRAM THE FSU REAL ESTATE CENTER’S 24TH REAL ESTATE TRENDS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 25 & 26 , 2 0 18 TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA LEGACY LEADERS GOLD SPONSORS PROGRAM PARTNERS The Real Estate TRENDS Conference is organized to inform participants of the The Program Partner designation is reserved for emerging trends and issues facing the real estate industry, to establish and strengthen those who have made major gifts to advance the professional contacts, and to present the broad range of career opportunities available Real Estate Program at Florida State University. to our students. It is organized by the FSU Real Estate Center, the Florida State University Donna Abood Real Estate Network and the students’ FSU Real Estate Society. This event would not be Beth Azor possible without the generous financial support of its sponsors. Kenneth Bacheller Mark C. Bane Bobby Byrd LEGACY LEADERS Harold and Barbara Chastain Centennial Management Corp. Marshall Cohn Peter and Jennifer Collins JLL John Crossman/Crossman & Company The Kislak Family Foundation, Inc. Scott and Marion Darling Florida State Real Estate Network, Inc. Mark and Nan Casper Hillis Evan Jennings GOLD SPONSORS The Kislak Family Foundation, Inc. • Berkadia • Cushman & Wakefield • Lennar Homes Brett and Cindy Lindquist • Carroll Organization • The Dunhill Companies • The Nine @ Tallahassee George Livingston William and Stephanie Lloyd • CBRE • Eastdil Secured • Osprey Capital Shawn McIntyre/North American Properties • CNL Financial Group, Inc. • Florida Trend • Ryan, LLC Greg Michaud • Colliers International • Gilbane Building Company • Stearns Weaver Miller Kyle Mowitz and Justin Mowitz • Commercial Capital LTD • GreenPointe Communities, LLC • STR, Inc. Francis Nardozza • Culpepper Construction • Hatfield Development/Pou • Walker & Dunlop Kyle D. -

Policy and Politics by the Numbers;Аfor the President

5/12/2017 Policy and Politics by the Numbers; For the President, Polls Became a Defining Force in His Administration washingtonpost.com search nation, world… Policy and Politics by the Numbers; For the President, Polls Became a Defining Force in His Administration [FINAL Edition] The Washington Post Washington, D.C. Subjects: Series & special reports; Public opinion surveys; Policy making; Presidency Author: Harris, John F Date: Dec 31, 2000 Start Page: A.01 Section: A SECTION One night a week, a select group of White House aides and Cabinet members would file into the Yellow Oval Room in the White House residence. And Bill Clinton, the most polished and talkative politician of his era, for once would let someone else do the talking: a disheveled man who even friends say was ill at ease except when the conversation turned to numbers. The man was Clinton's pollster. The weekly residence meeting was the place where this president got his fix of the data that drove a presidency. As Clinton prepares to leave office 20 days from now, even his sharpest critics bow to his mastery of politics. This was a president who understood his times and became the dominant voice of them, who faced every conceivable adversity yet managed still to survive and prosper. What is less understood is that Clinton's political gifts were more than the magic of personality. They were a set of precise techniques that relied on constant gauging of public opinion, and constant responses to it in ways large and small. So Clinton's legacy is in many ways a story about polls. -

Hillary Clinton's Campaign Was Undone by a Clash of Personalities

64 Hillary Clinton’s campaign was undone by a clash of personalities more toxic than anyone imagined. E-mails and memos— published here for the first time—reveal the backstabbing and conflicting strategies that produced an epic meltdown. BY JOSHUA GREEN The Front-Runner’s Fall or all that has been written and said about Hillary Clin- e-mail feuds was handed over. (See for yourself: much of it is ton’s epic collapse in the Democratic primaries, one posted online at www.theatlantic.com/clinton.) Fissue still nags. Everybody knows what happened. But Two things struck me right away. The first was that, outward we still don’t have a clear picture of how it happened, or why. appearances notwithstanding, the campaign prepared a clear The after-battle assessments in the major newspapers and strategy and did considerable planning. It sweated the large newsweeklies generally agreed on the big picture: the cam- themes (Clinton’s late-in-the-game emergence as a blue-collar paign was not prepared for a lengthy fight; it had an insuf- champion had been the idea all along) and the small details ficient delegate operation; it squandered vast sums of money; (campaign staffers in Portland, Oregon, kept tabs on Monica and the candidate herself evinced a paralyzing schizophrenia— Lewinsky, who lived there, to avoid any surprise encounters). one day a shots-’n’-beers brawler, the next a Hallmark Channel The second was the thought: Wow, it was even worse than I’d mom. Through it all, her staff feuded and bickered, while her imagined! The anger and toxic obsessions overwhelmed even husband distracted. -

![Ittqvo W]\ Wn Tw^M Q\P 7Jiui](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1818/ittqvo-w-wn-tw-m-q-p-7jiui-511818.webp)

Ittqvo W]\ Wn Tw^M Q\P 7Jiui

V16, N5 Thursday, Sept. 9, 2010 Falling out of love with Obama Blue Hoosier state turns on president as economy sputters By BRIAN A. HOWEY STORY, Ind. - There was a barn sale in the bucolic hills of Brown County on Sunday and as people milled around the tables of used tools and clothes the talk turned to politics and, ultimately, President Obama. “He’s the worst president ever,” a woman said. Why would you say that? “He’s against capitalism,” she responded. This is not an isolated dynam- ic in the Hoosier State where Barack Obama carried with 51 percent of the vote in 2008. Whether it was The NRCC is running the TV ad (above) tying a speech before the Rotary Club in U.S. Rep. Joe Donnelly to President Obama Wabash, at a pub in Fremont, or at a and Speaker Pelosi. At right, President Obama funeral service in Mexico, Ind., when went on the offensive in Parma, Ohio on the topic turned to the president, Wednesday, answering in a speech charges there was open contempt, disgust made by House Minority Leader John Boehner. Continued on page 4 Obama at low ebb By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS - Obama wept. No, this isn’t news media fawning. It really hap- pened at the American Legion Mall in Indianapolis on the UA look around the American night of May 5, 2008. Some 21,000 Hoosiers gathered at the park to listen to Stevie Wonder and economy suggests itXs time to !"#$%"#&'%&%[$&)%*'#+*',-&'.%*,!/"%0'1-% Sen. Barack Obama in his race against break out the brandy. -

Transforming Marketing Forward Looking Information & Other Information

TRANSFORMING MARKETING FORWARD LOOKING INFORMATION & OTHER INFORMATION Cautionary Statement Regarding Forward-Looking Statements This communication may contain certain forward-looking statements (collectively, “forward-looking statements”) within the meaning of Section 27A of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended and Section 21E of the U.S. Exchange Act and the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, as amended, and “forward-looking information” under applicable Canadian securities laws. Statements in this document that are not historical facts, including statements about MDC’s or Stagwell’s beliefs and expectations and recent business and economic trends, constitute forward-looking statements. Words such as “estimate,” “project,” “target,” “predict,” “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “potential,” “create,” “intend,” “could,” “should,” “would,” “may,” “foresee,” “plan,” “will,” “guidance,” “look,” “outlook,” “future,” “assume,” “forecast,” “focus,” “continue,” or the negative of such terms or other variations thereof and terms of similar substance used in connection with any discussion of current plans, estimates and projections are subject to change based on a number of factors, including those outlined in this section. Such forward-looking statements may include, but are not limited to, statements related to: future financial performance and the future prospects of the respective businesses and operations of MDC, Stagwell and the combined company; information concerning the proposed business combination -

January 2017 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

January 2017 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data January 1, 2017 28 men and 17 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 7 men and 2 women Joe Lockhart (M) Nicolle Wallace (F) Ari Fleischer (M) David Folkenflik (M) Hal Boedeker (M) Claire Atkinson (F) Gabe Sherman (M) Gerard Baker (M) Dean Baquet (M) CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 4 men and 4 women Isabel Wilkerson (F) J.D. Vance (M) Diane Guerrero (F) Amani Al-Khatahthbeh (F) Michele Norris (F) Jeffrey Goldberg (M) Michael Gerson (M) David Frum (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 5 men and 4 women *Hosted by Jonathan Karl Incoming White House Communications Director, Sean Spicer (M) Rep. Adam Schiff (M) Donna Brazile (F) Former Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich (M) Sarah Haines (F) Steve Inskeep (M) Karine Jean-Pierre (F) Kevin Madden (M) Mary Bruce (F) CNN's State of the Union with Jake Tapper: 6 men and 5 women Rep. Charlie Crist (M) Rep. Marsha Blackburn (F) Rep. Darrell Issa (M) Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester (F) Jim Acosta (M) Salena Zito (F) Abby Phillip (F) Jeff Zeleny (M) Former Governor Brian Schwietzer (M) Karen Finney (F) Van Jones (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 6 men and 2 women *Hosted by Shannon Bream Sen. Tom Cotton (M) Leonard Leo (M) Austan Goolsbee (M) Steve Moore (M) Lisa Boothe (F) Julie Roginsky (F) Daniel Halper (M) Charles Hurt (M) January 8, 2017 19 men and 12 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 5 men and 3 women Sen. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

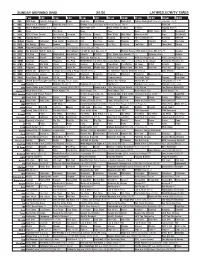

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Need-See Bull Riding Basketball College Basketball Xavier at Georgetown. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Philadelphia Flyers at New York Rangers. (N) Å PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Flipping Houses 7 ABC News This Week News News News ABC7 Game NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Help Now! Women on the Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Flipping Houses Fox News Sunday News The Issue Flipping Paid Prog. PBC Countdown (N) RaceDay NASCAR 1 3 MyNet Flipping Concealer Fred Jordan Freethought AAA Paid Prog. Secrets Flipping AAA Flipping News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Get Energy Smile Income AAA Paid Prog. Hempvana Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Foot Pain AAA Toned Abs Omega 2 2 KWHY Programa pagado Programa que muestra diversos productos para la venta. (6) (TVG) 2 4 KVCR The Keto Diet With Dr. Josh Axe The Collagen Diet with Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Å Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Sesame 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Wunderkind Wunderkind Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Elvis, Aloha From Hawaii (TVG) Å Relieving Stress Antoine 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid Prog. -

Profiles in Manufacturing 09-07-17

Profiles in American Solar Manufacturing First Edition August 2017 Introduction American solar manufacturing is a diverse economic powerhouse that employs 38,000 workers. There are more than 600 facilities in the United States that manufacture for the solar industry. The products these companies make include steel and polysilicon, inverters and trackers, cabling and combiner boxes, and cells and panels. They also fabricate racking and mounting systems and they are innovating every step of the way. If the International Trade Commission approves Suniva’s remedy, much of the manufacturers profiled here will be severely injured and the number of jobs potentially lost will be many times those temporarily gained by the petitioners. The companies mentioned here are owned by Americans and overseas investors, but they all have one thing in common, they have found a way to compete in the marketplace, through innovation, efficiency and good business decisions. Solar Panel Prices vs Solar Manufacturing Jobs Graph courtesy of Cypress Creek Renewables SEIA | www.seia.org Profiles in American Solar Manufacturing August 2017 Fronius Portage, Indiana 100 employees Fronius USA opened its doors in 2002 and is making a significant contribution to the American solar market. With its headquarters centrally located in the Midwest, and other satellite offices throughout the USA, Fronius is positioned as one of America’s leading solar inverter makers and provides American jobs in solar technical support, warehouse and assembly, service and sales. This company has thrived because of innovation. It started exploring the solar business in the mid-1990s and has grown from there. Image courtesy of Fronius “It’s very important for us to support U.S. -

Faculty News

4/7/14 4:46 PM Web Version | Update preferences | Unsubscribe Like Tweet Forward TABLE OF CONTENTS Faculty News • Faculty News • Student News Assistant Professor Yvonnes Chen's co-authored abstract was • Guest Speakers accepted for oral presentation at the 2014 Society for Nutrition Eduation and Behavior (SNEB) conference. Chen is the first author on • Visitors this study, which examined the relationship between health literacy • Student and media literacy related to sugar-sweetened beverages. Opportunities • Mark Your Calendar Associate Professor Tim Bengtson’s Media Writing students will visit with Lawrence Journal-World reporters on Thursday, April 3, to review recent extended news stories that appeared in the newspaper. The students also will tour the Journal-World’s facility. Associate Professor Mugur Geana has been asked to serve as a panelist at the 2014 Joan Berkley Bioethics Symposium on April 25, 2014. The event, organized by the Center for Practical Bioethics, brings together clinicians, patients, patient advocates, researchers and non-profit organizations to discuss about promoting continuous improvement in quality of care and about ethical issues linked to the transformations that the US health care system is currently undergoing. Dr. Geana will talk about how public health and mass media research can be used to better inform journalists, clinicians and the general public about important health care issues. Associate Professor Doug Ward, Assistant Professor Yvonnes Chen, School bibliographer Julie Petr and doctoral student Kristen Grimmer are serving on a committee to revamp the journalism master’s program. They have scheduled these two open meetings in 303 Stauffer-Flint to invite input from faculty: Thursday, April 10, noon to 1 Wednesday, April 16, 2 to 3:30 https://universityofkansasschoolofjournalism.createsend.com/t/ViewEmail/i/6CB0D1FBC46D70C1/C67FD2F38AC4859C/ Page 1 of 5 4/7/14 4:46 PM Student News Congrats, Sam Logan! Last Tuesday, the KU Prize Patrol dropped by Sam Logan’s class to award him the Caryl K. -

Campaigning to Govern: Presidents Seeking Reelection1

Campaigning to Govern: Presidents Seeking Reelection1 n the presidential election of 1904, President president and candidate, to what extent does I Theodore Roosevelt refrained from cam- the quest for reelection affect “business as paigning as it was considered “undignified to usual” within the White House? This essay campaign from the White House”(Troy 1991, addresses these questions, drawing attention to 212 emphasis added). This fear of losing the mechanics of presidential reelection cam- one’s “dignity” had gone by the wayside when paigns as well as their impact on the White President Woodrow Wilson actively cam- House. paigned for his 1916 reelection. Since then, there’s been no turning back. Dramatic ad- Trying to Control the vancements in telecommunications have made Uncontrollable presidents ubiquitous—campaigning on day- time talk shows, MTV, and internet sites have Given the uncertainty of nomination politics, become de rigeur. These days, the notion of particularly in the aftermath of the presidents campaigning for reelection is com- McGovern-Fraser Commission, the White monplace. In fact, when presidents claim that House is wary of nomination challenges and they are avoiding the campaign trail to take where possible, works to prevent them. In care of government business, journalists and 1977, the Winograd Commission met to revise observers scoff in disbelief. the Democratic nominating rules. Needless to In their quest for reelection, presidents have say, White House advisors were instrumental tremendous campaign assets: unbeatable name in producing a set of reforms that would bene- recognition, a coterie of strategists with the fit Jimmy Carter’s efforts in 1980 (Lengle greatest incentive to 1987, 242). -

Hbo Premieres Hbo Film: Game Change

HBO PREMIERES HBO FILM: GAME CHANGE HBO PREMIERES HBO FILM: GAME CHANGE Starring Julianne Moore as Sarah Palin and Ed Harris as John McCain, the film debuts May 5th in the Caribbean Miami, April 30th, 2012 – HBO Latin America announced the May 5th premiere of the original HBO Film Game Change in the Caribbean. Starring Julianne Moore as Sarah Palin and Ed Harris as John McCain, the film is an adaptation of the non-fiction best-selling book, Game Change, which offers an insider’s look at the 2008 presidential campaign, shedding particular light on Governor Sarah Palin’s road to national fame. From executive producers Tom Hanks and Gary Goetzman, Game Change offers a searing, behind-the-scenes look at John McCain’s (Ed Harris) 2008 vie for presidency, from the decision to select Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as McCain’s running mate to the ticket’s ultimate defeat in the general election just sixty days later. Told primarily through the eyes of senior McCain strategist Steve Schmidt (Woody Harrelson), who originally championed Palin and later came to regret the choice, Game Change pulls back the curtain on the intense human drama surrounding the McCain team, the predicaments encountered behind closed doors and how the choice was made to incorporate Palin into a high profile national campaign despite growing fears of the governor’s lacking knowledge in world affairs. As the film reveals, McCain strategists viewed the selection of a running mate as their last, and perhaps only, chance to catch Barack Obama.