Working Paper Nº 01/13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lacoste Press Kit 2011

Press Kit LACOSTE S.A. The LACOSTE legend was born in 1933, when René Lacoste revolutionized mens’ fashion replacing the classical woven fabric, long-sleeved and starched shirts on the courts, by what has now become the classic LACOSTE polo shirt. 78 years after its creation, LACOSTE has become a « lifestyle » brand which allies elegance and comfort. The LACOSTE art of living expresses itself today through a large collection of apparel for women, men and children, footwear, fragrances, leather goods, eyewear, watches, belts, home textiles, mobile phones and fashion jewelry. LACOSTE founds its success on the essential values of authenticity, performance, and elegance. The crocodile incarnates today the elegance of the champion, René Lacoste, as well as of his wife Simone Lacoste and their daughter Catherine Lacoste, both also champions, in everyday life as on the tennis courts and golf courses. Key Figures (31/12/10) - 2 LACOSTE items sold every second worldwide. - Wholesale Turnover 1,4 billion euros, 90% of which is out of France Michel Lacoste is Chairman of the Board of LACOSTE S.A. since April, 2008. Christophe Chenut is CEO of LACOSTE S.A. since April, 2008. LACOSTE S.A. is owned 65% by the Lacoste family and 35 % by Devanlay (Maus family). LACOSTE S.A. owns simultaneously 10% of Devanlay, its worldwide clothing licencee. A worldwide presence in 114 countries The most important markets in order of importance are : the USA, France, Italy, UK and Spain ASIA EUROPE 18 * 48 * A selective distribution throughout - more than 1100 LACOSTE boutiques MIDDLE-EAST - more than 2000 «corners» in department stores AMERICA 13 * - specialized outlets and sports stores 26 * AFRICA 7 * OCEANIA 2 * * Number of countries by continent :21/02/11 date p u t s La Press Kit LACOSTE S.A. -

Page 01 Jan 16.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Wednesday 16 January 2013 4 Rabial I 1434 - Volume 17 Number 5581 Price: QR2 Qatar committed UAE and Iraq to sustainable reach Gulf growth: Al Sada Cup final Business | 17 Sport | 27 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Jewish pianist Emir meets Libya’s Interim PM wows crowds at Katara Debate over inviting Israeli to Qatar BY RAYNALD RIVERA those who are making noise (a reference to Barenboim’s critics) DOHA: Hundreds of music that he is a famous and excellent enthusiasts, including Qatari musician. Although Israeli Jewish, men and women, gave a stand- he is an open backer of the peo- ing ovation to renowned pianist ple of Palestine and Gaza,” said and composer Daniel Barenboim another. after an enthralling performance “Barenboim calls himself secu- by him at the Katara Cultural lar and progressive. He is a man Village here yesterday. of peace,” he added, even as many There were doubts whether of the musician’s critics dubbed anyone, especially Qatari citizens, yesterday’s event a shame. The Emir H H Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani with Libya’s Interim Prime Minister Ali Zaidan Mohammad and his accompanying delegation at would turn out for the perform- “We couldn’t get hold of any the Emiri Diwan yesterday. They discussed bilateral ties and means to develop them. ance by Barenboim, a Jew, after other musician?, asked an angered media reports about his visit Qatari. “Our country has a led to a heated debate on local respectable stance vis-à-vis the social networking sites, stoking a Palestinian issue, but this event controversy. -

Iowa City, Iowa - Wednesday, September 2, 2009 News Dailyiowan.Com for More News

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2009 SPORTS No Go Bejeweled no more Zone Iowa head coach Kirk Ferentz reveals that sophomore run- ning back Jewel Hampton is Some food vendors out for the season with a leg injury. 12 are cautious Iron ridge about delivering The Iowa men’s golf team takes to the city’s second at the Golfweek Conference Challenge on Tuesday. 12 Southeast Side. By DANNY VALENTINE NEWS [email protected] Rushin’ to take One local business will no Russian longer deliver pizzas to the city’s Southeast Side after An increasing number of UI JOE SCOTT/THE DAILY IOWAN two of its employees were students are opting to take Yellow Cab driver Roman Schoenberger heads up Burlington Street on Tuesday on his way to a fare. Yellow Cab is the only company in recently robbed at gunpoint. classes in Russian. 2 town that accepts Cab Cash, a debit-style card that people can use for rides home. The decision came after a Meet the third armed robbery on Monday night, which even- candidates tually resulted in the arrest Read what the six Iowa City of three men who are School Board candidates have Iowa City hails cab card allegedly connected to the to say about district issues. 2 two pizza-delivery incidents University Cab Cash and one other case. ARTS & CULTURE The days of students standing on the curb, Reginald Payne, 20, The program cites drunk driving as an Laron James, 19, both of More typical ethnic wishing for money for a cab, are over. incentive for using its service. -

In Order of Play by Court

ABIERTO MEXICANO TELCEL presented by HSBC: DAY 3 MEDIA NOTES Wednesday, February 24, 2016 Acapulco Princess Mundo Imperial, Acapulco, Mexico | February 22 – February 27, 2016 Draw: S-32, D-16 | Prize Money: $1,413,600 | Surface: Outdoor Hard ATP Info: Tournament Info: ATP PR & Marketing: www.ATPWorldTour.com www.abiertomexicanodetenis.com Edward La Cava: [email protected] @ATPWorldTour @AbiertoTelcel Greg Sharko: [email protected] facebook.com/ATPWorldTour facebook.com/AbiertoMexicanoDeTenis Press Room: + 52 744 466 3899 FERRER, NISHIKORI, THIEM FEATURED ON WEDNESDAY DAY 3 PREVIEW: David Ferrer, Kei Nishikori and Dominic Thiem are featured as all eight second round matches are scheduled on Wednesday at Acapulco. All together there are 12 matches scheduled (8 singles, 4 doubles). Top seed and four-time champion Ferrer gets the second round started on Cancha Central when he faces Alexandr Dolgopolov for the 11th time. The World No. 8 Ferrer holds an 8-2 head-to-head advantage. The Spaniard has reached the quarter-finals or better in four of five events played this year. Dolgopolov has a career 8-36 record (0-1 in 2016) vs Top 10 opponents. Has lost three straight, last win was last year over No. 6 Tomas Berdych in quarter-finals at ATP Masters 1000 Cincinatti. American Sam Querrey looks to snap a four match losing streak to the No. 2 seed Nishikori in the first match of the evening session (Nishikori leads 5-3). The American is looking to reach his third consecutive ATP World Tour quarter-final. Last week he captured his eighth career ATP World Tour title at Delray Beach (d. -

2020 Women’S Tennis Association Media Guide

2020 Women’s Tennis Association Media Guide © Copyright WTA 2020 All Rights Reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying- without the written permission of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Compiled by the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Communications Department WTA CEO: Steve Simon Editor-in-Chief: Kevin Fischer Assistant Editors: Chase Altieri, Amy Binder, Jessica Culbreath, Ellie Emerson, Katie Gardner, Estelle LaPorte, Adam Lincoln, Alex Prior, Teyva Sammet, Catherine Sneddon, Bryan Shapiro, Chris Whitmore, Yanyan Xu Cover Design: Henrique Ruiz, Tim Smith, Michael Taylor, Allison Biggs Graphic Design: Provations Group, Nicholasville, KY, USA Contributors: Mike Anders, Danny Champagne, Evan Charles, Crystal Christian, Grace Dowling, Sophia Eden, Ellie Emerson,Kelly Frey, Anne Hartman, Jill Hausler, Pete Holtermann, Ashley Keber, Peachy Kellmeyer, Christopher Kronk, Courtney McBride, Courtney Nguyen, Joan Pennello, Neil Robinson, Kathleen Stroia Photography: Getty Images (AFP, Bongarts), Action Images, GEPA Pictures, Ron Angle, Michael Baz, Matt May, Pascal Ratthe, Art Seitz, Chris Smith, Red Photographic, adidas, WTA WTA Corporate Headquarters 100 Second Avenue South Suite 1100-S St. Petersburg, FL 33701 +1.727.895.5000 2 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Women’s Tennis Association Story . 4-5 WTA Organizational Structure . 6 Steve Simon - WTA CEO & Chairman . 7 WTA Executive Team & Senior Management . 8 WTA Media Information . 9 WTA Personnel . 10-11 WTA Player Development . 12-13 WTA Coach Initiatives . 14 CALENDAR & TOURNAMENTS 2020 WTA Calendar . 16-17 WTA Premier Mandatory Profiles . 18 WTA Premier 5 Profiles . 19 WTA Finals & WTA Elite Trophy . 20 WTA Premier Events . 22-23 WTA International Events . -

2020 Us Open Singles Prize Money & Ranking Points

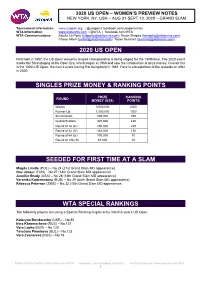

2020 US OPEN – WOMEN’S PREVIEW NOTES NEW YORK, NY, USA – AUG 31-SEPT 13, 2020 – GRAND SLAM Tournament Information: www.usopen.org | @usopen | facebook.com/usopentennis WTA Information: www.wtatennis.com | @WTA | facebook.com/WTA WTA Communications: Estelle La Porte ([email protected]), Bryan Shapiro ([email protected]), Chase Altieri ([email protected]), Teyva Sammet ([email protected]) 2020 US OPEN First held in 1887, the US Open women’s singles championship is being staged for the 134th time. The 2020 event marks the 53rd staging of the Open Era, which began in 1968 and saw the introduction of prize money. Overall this is the 140th US Open, the men’s event having first being held in 1881. Here is a breakdown of the rewards on offer in 2020: SINGLES PRIZE MONEY & RANKING POINTS PRIZE RANKING ROUND MONEY (US$) POINTS Winner 3,000,000 2000 Runner-Up 1,500,000 1300 Semifinalists 800,000 780 Quarterfinalists 425,000 430 Round of 16 (4r) 250,000 240 Round of 32 (3r) 163,000 130 Round of 64 (2r) 100,000 70 Round of 128 (1r) 61,000 10 SEEDED FOR FIRST TIME AT A SLAM Magda Linette (POL) – No.24 (21st Grand Slam MD appearance) Ons Jabeur (TUN) – No.27 (14th Grand Slam MD appearance) Jennifer Brady (USA) – No.28 (13th Grand Slam MD appearance) Veronika Kudermetova (RUS) – No.29 (sixth Grand Slam MD appearance) Rebecca Peterson (SWE) – No.32 (10th Grand Slam MD appearance) WTA SPECIAL RANKINGS The following players are using a Special Ranking to gain entry into this year’s US Open: Kateryna Bondarenko (UKR) – No.85 Irina Khromacheva (RUS) – No.137 Vera Lapko (BLR) – No.120 Tsvetana Pironkova (BUL) – No.123 Vera Zvonareva (RUS) – No.78 Follow WTA on Twitter: www.twitter.com/WTA Facebook: www.facebook.com/WTA YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/WTA 1 2020 US OPEN – WOMEN’S PREVIEW NOTES NEW YORK, NY, USA – AUG 31-SEPT 13, 2020 – GRAND SLAM ACTIVE GRAND SLAM CHAMPIONS The 2020 season has already welcomed one new Grand Slam champion: Sofia Kenin won her maiden Grand Slam singles title at Melbourne Park in January, defeating Garbiñe Muguruza in the final. -

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest for Perfection

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER New Chapter Press Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic Originally published in Germany under the title “Das Tennis-Genie” by Pendo Verlag. © Pendo Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich and Zurich, 2006 Published across the world in English by New Chapter Press, www.newchapterpressonline.com ISBN 094-2257-391 978-094-2257-397 Printed in the United States of America Contents From The Author . v Prologue: Encounter with a 15-year-old...................ix Introduction: No One Expected Him....................xiv PART I From Kempton Park to Basel . .3 A Boy Discovers Tennis . .8 Homesickness in Ecublens ............................14 The Best of All Juniors . .21 A Newcomer Climbs to the Top ........................30 New Coach, New Ways . 35 Olympic Experiences . 40 No Pain, No Gain . 44 Uproar at the Davis Cup . .49 The Man Who Beat Sampras . 53 The Taxi Driver of Biel . 57 Visit to the Top Ten . .60 Drama in South Africa...............................65 Red Dawn in China .................................70 The Grand Slam Block ...............................74 A Magic Sunday ....................................79 A Cow for the Victor . 86 Reaching for the Stars . .91 Duels in Texas . .95 An Abrupt End ....................................100 The Glittering Crowning . 104 No. 1 . .109 Samson’s Return . 116 New York, New York . .122 Setting Records Around the World.....................125 The Other Australian ...............................130 A True Champion..................................137 Fresh Tracks on Clay . .142 Three Men at the Champions Dinner . 146 An Evening in Flushing Meadows . .150 The Savior of Shanghai..............................155 Chasing Ghosts . .160 A Rivalry Is Born . -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17523 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE DIMANCHE 27 - LUNDI 28 MAI 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI L’autoportrait de Lionel Jospin Deux milliardaires dans la guerre de l’art b Après le luxe et la distribution, les deux hommes les plus riches de France s’affrontent sur le marché en candidat de l’art b Avec la maison d’enchères Phillips, Bernard Arnault cherche à détrôner le leader Christie’s, à l’élection propriété de François Pinault b Enquête sur un duel planétaire autour de sommes mirobolantes APRÈS le luxe, la distribution et la impitoyable : pour détrôner Chris- présidentielle nouvelle économie, le marché de tie’s, M. Arnault n’hésite pas à pren- l’art est le nouveau terrain d’affronte- dre de considérables risques finan- PATRICK KOVARIK/AFP A L’OCCASION du quatrième ment des deux hommes les plus ciers. Ce duel, par commissaires- anniversaire de son entrée à Mati- riches de France : Bernard Arnault priseurs interposés, constitue un nou- GRAND PRIX DU « MIDI LIBRE » gnon, Lionel Jospin franchit, dans (propriétaire de Vuitton, Dior, Given- veau chapitre de la mondialisation Le Figaro magazine, un pas de plus chy, Kenzo, Moët et Chandon, Hen- du marché de l’art. En 1999, Phillips vers sa candidature à l’élection pré- nessy…) et François Pinault (Gucci, et Christie’s étaient deux vénérables Gruppetto sidentielle. Dans un article accom- La Fnac, Le Printemps, La Redoute, maisons britanniques. Elles sont pagné par des photographies de sa Conforama…). Pour la première fois, aujourd’hui détenues par des Fran- vie quotidienne, réalisées par Ray- en mai, la maison d’enchères çais. -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d. -

The Championships 2002 Gentlemen's Singles Winner: L

The Championships 2002 Gentlemen's Singles Winner: L. Hewitt [1] 6/1 6/3 6/2 First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Quarter-Finals Semi-Finals Final 1. Lleyton Hewitt [1]................................(AUS) 2. Jonas Bjorkman................................... (SWE) L. Hewitt [1]..................... 6/4 7/5 6/1 L. Hewitt [1] (Q) 3. Gregory Carraz..................................... (FRA) ....................6/4 7/6(5) 6/2 4. Cecil Mamiit.......................................... (USA) G. Carraz................6/2 6/4 6/7(5) 7/5 L. Hewitt [1] 5. Julian Knowle........................................(AUT) .........................6/2 6/1 6/3 6. Michael Llodra.......................................(FRA) J. Knowle.............. 3/6 6/4 6/3 3/6 6/3 J. Knowle (WC) 7. Alan MacKin......................................... (GBR) .........................6/3 6/4 6/3 8. Jarkko Nieminen [32]........................... (FIN) J. Nieminen [32]..........7/6(5) 6/3 6/3 L. Hewitt [1] 9. Gaston Gaudio [24]............................ (ARG) .........................6/3 6/3 7/5 (Q) 10. Juan-Pablo Guzman.............................(ARG) G. Gaudio [24]................. 6/3 6/4 6/3 M. Youzhny (LL) 11. Brian Vahaly......................................... (USA) ........6/0 1/6 7/6(2) 5/7 6/4 12. Mikhail Youzhny................................... (RUS) M. Youzhny.................6/3 1/6 6/3 6/2 M. Youzhny 13. Jose Acasuso....................................... (ARG) ...................6/2 1/6 6/3 6/3 14. Marc Rosset........................................... (SUI) M. Rosset..................... 6/3 7/6(4) 6/1 N. Escude [16] (WC) 15. Alex Bogdanovic...................................(GBR) ...................6/2 5/7 7/5 6/4 16. Nicolas Escude [16]............................ (FRA) N. Escude [16]........... 4/6 6/4 6/4 6/4 17. Juan Carlos Ferrero [9]...................... (ESP) 18. -

Tournament Notes

TOURNAMENT NOTES as of January 28, 2016 RBC TENNIS CHAMPIONSHIPS OF DALLAS DALLAS, TX • JANUARY 30 – FEBRUARY 6 USTA PRO CIRCUIT RETURNS TO DALLAS TOURNAMENT INFORMATION The RBC Tennis Championships of Dallas brings the USTA Pro Circuit to Dallas for the Site: T Bar M Racquet Club – Dallas, Texas 16th consecutive year and 19th year overall. (The event was not held in 2000.) This Websites: www.tennischampinoshipsofdallas.com marks the fifth year the event has offered Dishman USTA/Ned procircuit.usta.com $100,000 in prize money, up from $50,000 Facebook: Tennis Championships of Dallas in 2011. It is the only USTA Pro Circuit Twitter: @RBCTennisChamps Challenger hosted in Texas. Qualifying Draw Begins: Saturday, Jan. 30 This tournament will be streamed live on Main Draw Begins: Monday, Feb. 1 www.procircuit.usta.com. To follow the tournament, download the USTA Pro Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles Circuit’s new phone app for smartphones Surface: Hard / Indoor and tablets by searching “procircuit” in the Prize Money: $100,000 Apple and Google Play stores. Tournament Director: Notable players competing in Dallas include: Darren Boyd, (972) 385-3613, [email protected] Tournament Manager: Dallas defending singles champion Tim Chris Wade, (972) 385-3632, [email protected] Smyczek, who peaked at No. 68 in the world in April 2015 after qualifying for the main Tournament Press Contact: draw of the Australian Open and winning Dallas defending singles champion Tim Smyczek Krista Maldonado, (972) 385-3609 his first-round match. In the second round, peaked at No. 68 in the world in April 2015. -

Tournament Notes

TournamenT noTes as of march 31, 2010 THE RIVER HILLS USTA $25,000 WOMEN’S CHALLENGER JACKSON, MS • APRIL 4-11 USTA PRO CIRCUIT RETURNS TO JACKSON FOR 12TH STRAIGHT YEAR TournamenT InFormaTIon The River Hills USTA $25,000 Women’s Challenger is the 10th $25,000 women’s tournament of the year and the only $25,000 Site: River Hills Country Club – Jackson, Miss. women’s event held in Mississippi. Jackson Websites: www.riverhillsclub.net, is the second of three consecutive clay court procircuit.usta.com events on the USTA Pro Circuit in the lead-up to the 2010 French Open. Bryn Lennon/Getty Images Qualifying draw begins: Sunday, April 4 Main draw begins: Tuesday, April 6 This year’s main draw is expected to include Julia Cohen, an All-American at the University Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles of Miami who reached the semifinals of the NCAA tournament as a sophomore in 2009, Surface: Clay / Outdoor Lauren Albanese, who won the 2006 USTA Prize Money: $25,000 Girls’ 18s National Championships to earn an automatic wild card into the US Open, and Tournament Director: Kimberly Couts, a frequent competitor on the Dave Randall, (601) 987-4417 USTA Pro Circuit who won the 2006 Easter Lauren Albanese won the 2006 USTA Girls’ [email protected] Bowl as a junior and was a former USTA Girls’ 18s National Championships to earn an 16s No. 1. automatic wild card into the US Open. Tournament Press Contact: Kendall Poole, (601) 987-4454 International players in the main draw include freshman in 2009 and led Duke University [email protected]