BCT S-2 Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

Combat Infantrymen

1st Cavalry Division Association Non-Profit Organization 302 N. Main St. US. Postage PAID Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 West, TX 76691 Change Service Requested Permit No. 39 SABER Published By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 69 NUMBER 4 Website: www.1CDA.org JULY / AUGUST 2020 This has been a HORSE DETACHMENT by CPT Siddiq Hasan, Commander THE PRESIDENT’S CORNER year different from We thundered into the summer change of command season with a cavalry Allen Norris any other for most of charge for 3rd ABCT’s change of command at the end of June. Our new First (704) 483-8778 us. By the time you Sergeant was welcomed into the ranks at the beginning of July at a key time in [email protected] read this Cathy and I our history with few public events taking place due to COVID-19 but a lot of will have moved into foundational training taking place. We have taken this opportunity to conduct temporary housing. Sometime ago Cathy and I talked about the need to downsize. intensive horsemanship training for junior riders, green horses and to continue Until this year it was always something to consider later. In January we decided with facility improvements. The Troopers are working hard every day while that it was time. We did not want to be in a retirement community. We would like taking the necessary precautions in this distanced work environment to keep more diversity. Also, in those communities you have to pay for amenities that we themselves and the mounts we care for healthy. -

Brian Patrick Murray 1600 Beechwood Avenue, Fullerton, California 92835 1- 714 -990-3004 Studio 1-714-783-8565 Mobile [email protected]

Brian Patrick Murray 1600 Beechwood Avenue, Fullerton, California 92835 1- 714 -990-3004 studio 1-714-783-8565 mobile [email protected] Resume Education Concept Design Academy Fullerton College Otis Parsons School of Design Farmingdale State University of New York H. Frank Carey High Graduate Career History Owner/Illustrator, Murray Studios -- 1984 to present Produced concept art & storyboards for feature film & television, working side-by-side with top-tier Directors. Utilizing my expertise in Photoshop, and ZBrush, on a Cintiq monitor, increased my speed and productivity beyond industry peers, prompting one of the aforementioned Directors to claim I’m the best and fastest storyboard artist he has ever worked with Designed and illustrated comic book art for DC, Marvel, Image Comics, Extreme Studios, including Batman, Supreme, Young All-Stars, Ms Mystic, and more Designed and illustrated Tony Hawk's corporate logo, as well as many images that were produced on thousands of skateboards, sold across the nation Produced animation storyboards for Marvel Entertainment, and DIC Animation Visual Consultant for Relativity Media -- 2010 to 2015 Storyboarded, concepted art, and produced logo treatment designs while working with many Directors across as many films Instructor at Fullerton College -- 2013 to present Instructional courses include: “Storyboards and Sequence Design", and "Intro to Digital Painting" Art Director for Joseph Potocki and Associates -- 1984 to1987 Art Direction, Illustration, Design, and Comp Layouts for a variety of national and local accounts Film Credits "Ready Player One", Now You See Me 2", Super Troopers 2, Hunter Killer, "Earth to Echo", "Paranoia", "21 & Over", "Limitless", "Safe Haven", "Contraband", "Riddick", "The Chronicles of Riddick", "Pitch Black", "A Perfect Getaway", "Nightmare on Elm Street" (2009), "Green Lantern"(pitch package), "300", "Below", "Freddie vs. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

IA Giant n T Enters h e at the Battle: e r Order of Battle of the UN and Chinese Communist Forces in Korea, November 1950 by Troy J. Sacquety fter Inch’on and the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) abreakout from the Pusan Perimeter, the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) reeled back in shambles, their supply lines cut. On paper, the NKPA had a total of eight corps, thirty divisions, and several brigades, but in reality most were combat ineffective.1 Many North Korean units had fled north of the Yalu into Manchuria in order to refit and replenish their numbers. Only the IV Corps with one division and two brigades opposed the South Korean I Corps in northeastern Korea, and four cut-off divisions of II Corps and stragglers resorted to guerrilla operations near the 38th Parallel. South Korea provided soldiers, called “KATUSAs” to serve in U.S. With the war appearing won, only the Chinese and divisions alongside American soldiers. This soldier, nicknamed Soviet response to the potential Korean unification under “Joe” served in the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division. a democratic flag worried U.S. policymakers. Communist China was the major concern. Having just defeated Ground forces came from the United Kingdom (11,186), the Nationalist Chinese and reunified the mainland, the Turkey (5,051), the Philippines (1,349), Thailand (1,181), seasoned Red Army was five million strong. In fact, some Australia (1,002), The Netherlands (636), and India (326). of the best soldiers in the Chinese Communist Army were Sweden furnished a civilian medical contingent (168). -

FRONTLINE Hildner Field on Fort Hood December 6, 2013 | Volume III, Issue 45 Recently

FORSCOM in the news U.S. Army Forces Command The 13th Financial Management Support Center cased its colors in an inactivation ceremony at FRONTLINE Hildner Field on Fort Hood December 6, 2013 | Volume III, Issue 45 recently. Maj. Gen. Sean B. MacFarland, commanding FORSCOM Soldiers, civilians attend general, 1st Cavalry Division, hosted a change of Senior Leaders ‘high performance’ training responsibility ceremony for ‘America’s Corps’ in Japan the division. What was once simply “Our relationship with the Japanese known as Building 9420 has never been stronger. It’s absolutely was dedicated in honor of critical that we practice together to be ready to respond to anything as we one of 4th Infantry Brigade realign to the Pacific.” Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division’s fallen heroes. – Lt. Gen. Robert. B. Brown Commanding GeneraI, I Corps An infantryman with the 2nd Dec. 3, 2013, Hokkaido, Japan Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Exercise Yama Sukura 65 Airborne Division, received the Soldier’s Medal during On Point a ceremony held at Fort Bragg, N.C Be alert: Army Safe A food service specialist Winter Campaign with 17th Fires Brigade, 7th Infantry Division, was named The Army Safe Winter I Corps Cook of the Year, Campaign promotes junior Soldier category at awareness and Joint Base Lewis-McChord. individual responsibility among leaders, Soldiers, Gen. Daniel B. Allyn, commanding general U.S. Army Forces Command, discusses the command’s priorities with Family members and attendees at the U.S. Army High Performance Leader Development Program, Dec. 2, in Greensboro, N.C. (U.S. civilian employees to Army photo by Bob Harrison) Public Affairs units in action help prevent fatalities By Bob Harrison, FORSCOM Public Affairs “This is an effort within U.S. -

CHAPTER S1V the First Attack on the 1St Australian Division's New Front At

CHAPTER S1V THE BATTLE OF THE LYS-(11) APRIL llTH-%TEI THE first attack on the 1st Australian Division’s new front at Hazebrouck was made shortly after midnight of the 13th’ when a company of Germans came marching up a cross- country lane leading from Verte Rue to the Rue du Bois, across the Australian front. Behind a hedge bordering this lane was a Lewis gun post’ of Lieutenant Murdoch’s’ platoon of the centre company (Captain Fox’sS), 8th Battalion. The approaching troops, who were seen at some distance, were allowed to march without alarm to within twenty yards, when the Victorians blazed at them from every barrel, and continued to pour a withering fire into the Germans, whose survivors panicked and fled. Murdoch and some of his men went out and found a German officer and twenty men of the 141st Infantry Regiment dead, (Attack shown by artow.) and five abandoned machine-guns. Two nights later a sixth gun was found. The history of the I4rst I.R. (35th Division) states that on.ApriU 13, when the I and I1 Battalions of the regiment were held up after taking Verte Rue, the reserve battalion-the 111-was ordered to advance northwards on their right and seize Rue du Bois4 The battalion advanced in almost full force, with only the 10th company in reserve. “ Unfortunately,” says the history, “ no attack patrols were ahead of the front, and so it happened that, when the road had nearly been reached, machine-gun fire struck against the leading company. Many pressed back. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II. -

CHAPTER XXIII the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps Was

CHAPTER XXIII THE RELIEF BY THE MARINES THEAustralian and New Zealand Army Corps was originally to have been reinforced by Major-General Cox’ with the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade, which had been garrisoning the Canal at Suez. When the plans for the landing were being first drawn up, Hamilton intended to add a Gurkha brigade to the N.Z. and A. Division as its third brigade in place of the light horse and mounted rifles who were being left in Egypt. He was eventually promised Cox’s brigade, consisting of mixed Indian troops, but it had not yet arrived when the A. and N.Z. Corps left I-eninos for the landing. On Tuesday, April 27th, a message from Sir Ian Hamilton was circulated by the Corps Staff. “Well done, Anzac,” it said. “You are sticking it splendidly. Twenty-ninth Division has made good progress, and French Division is now landing to support it. An Indian brigade is on the sea and will join Anzac on arrival.” Rirdwood expected Cox’s Indians to arrive on April 27th and 28th; on the 30th he was still looking for them. Hamilton, however, quite rightly at the time, was far more anxious to use them in reaching Achi Baba while the Turks were still few in that quarter; and his diary shows that, if they had arrived on April 28th, they would have been thrown in at Helles. Hamilton did not realise that Birdwood’s Corps had until Wednesday been Withstanding nearly the whole of the Turkish striking force in the south of the Peninsula. -

The New Zealand Army Officer Corps, 1909-1945

1 A New Zealand Style of Military Leadership? Battalion and Regimental Combat Officers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces of the First and Second World Wars A thesis provided in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Wayne Stack 2014 2 Abstract This thesis examines the origins, selection process, training, promotion and general performance, at battalion and regimental level, of combat officers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces of the First and Second World Wars. These were easily the greatest armed conflicts in the country’s history. Through a prosopographical analysis of data obtained from personnel records and established databases, along with evidence from diaries, letters, biographies and interviews, comparisons are made not only between the experiences of those New Zealand officers who served in the Great War and those who served in the Second World War, but also with the officers of other British Empire forces. During both wars New Zealand soldiers were generally led by competent and capable combat officers at all levels of command, from leading a platoon or troop through to command of a whole battalion or regiment. What makes this so remarkable was that the majority of these officers were citizen-soldiers who had mostly volunteered or had been conscripted to serve overseas. With only limited training before embarking for war, most of them became efficient and effective combat leaders through experiencing battle. Not all reached the required standard and those who did not were replaced to ensure a high level of performance was maintained within the combat units. -

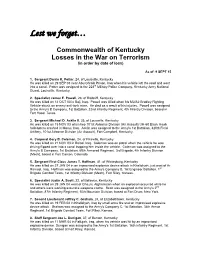

Lest We Forget…

Lest we forget… Commonwealth of Kentucky Losses in the War on Terrorism (in order by date of loss) As of: 9 SEPT 15 1. Sergeant Darrin K. Potter, 24, of Louisville, Kentucky He was killed on 29 SEP 03 near Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq when his vehicle left the road and went into a canal. Potter was assigned to the 223rd Military Police Company, Kentucky Army National Guard, Louisville, Kentucky. 2. Specialist James E. Powell, 26, of Radcliff, Kentucky He was killed on 12 OCT 03 in Baji, Iraq. Powell was killed when his M2/A2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle struck an enemy anti-tank mine. He died as a result of his injuries. Powell was assigned to the Army's B Company, 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, based in Fort Hood, Texas. 3. Sergeant Michael D. Acklin II, 25, of Louisville, Kentucky He was killed on 15 NOV 03 when two 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters crashed in Mosul, Iraq. Acklin was assigned to the Army's 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Kentucky. 4. Corporal Gary B. Coleman, 24, of Pikeville, Kentucky He was killed on 21 NOV 03 in Balad, Iraq. Coleman was on patrol when the vehicle he was driving flipped over into a canal trapping him inside the vehicle. Coleman was assigned to the Army's B Company, 1st Battalion, 68th Armored Regiment, 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division (Mech), based in Fort Carson, Colorado. 5. Sergeant First Class James T. Hoffman, 41, of Whitesburg, Kentucky He was killed on 27 JAN 04 in an improvised explosive device attack in Khalidiyah, just east of Ar Ramadi, Iraq.