Filipino American Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox (Guest: Amy Agbayani) 1

GUEST: AMY AGBAYANI LSS 410 (LENGTH: 26:46) FIRST AIR DATE: 11/30/10 I think people who don’t know me are really quite surprised when they do meet me, because I’m not frothing at the mouth. Because some of my statements might be outrageous, but on a personal level, I’m kind of mild, I think. But I do take strong positions on these issues. Have you taken a position, where you really put yourself out there on the very edge? Oh, yeah. Amy Agbayani came to Hawaii in the turbulent 1960s to get a graduate education, and she stayed to shake things up with her activist approach and sense of social justice. She has spent the past forty-plus years, on campus and in the community, chipping away at the barriers holding back immigrants, women, gays, and other underrepresented groups. Her story is next, on Long Story Short. Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaii’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition. Aloha mai kakou. I’m Leslie Wilcox. In this edition of Long Story Short, we’ll get to know Amy Agbayani, a Hawaii civil right pioneer who’s built a career and a reputation fighting for the underdog. Her activist roots date back to the anti- Vietnam War protests in the 60s at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Instead of returning to her native Philippines after graduate school, Dr. Agbayani found her calling in working to improve the lives of Filipino immigrants here in Hawaii. Over the years, she expanded her efforts to include other minorities and almost anyone on the fringes of society. -

Project-Based Language Teaching: a Collection of Teaching Activities

Project-based Language Learning with Computer Technology: A Collection of Teaching Activities Introduction Hanh thi Nguyen This collection of activities brings together some steps and some requirements for out- project-based learning or PBL (Beckett & comes), or free (the students determines Miller, 2006) and computer technology (see topic, process, and outcome). A key element also Debski, 2006). Projects for language in PBL is the use of naturally occurring (i.e., OHDUQLQJ DUH ´PXOWL-skill activities focusing authentic) information sources. It may in- on topics or themes rather than on specific volve face-to-face interviews, library re- ODQJXDJH WDUJHWV« %HFDXVH VSHFLILF ODn- search, internet search, email exchanges, and guage aims are not prescribed, and because field trips. students concentrate their efforts and atten- The outcomes of projects can be writ- tion on reaching an agreed goal, project ten reports, poster presentations, oral pres- work provides students with opportunities entations, multimedia presentations, videos, to recycle known language skills in a rela- portfolios, formation of a club, theatrical WLYHO\QDWXUDOFRQWH[Wµ +DLQHVS performance, exhibits in community, book- PBL is motivated by experiential learning lets, etc. Finally, projects typically involve (Dewey, 1938/1997) and his notion that authentic audiences: students write a letter students learn by doing and reflecting on to the editor, make a website for tourists, or their experience. produce a slide show for new students, and In PBL, the mode of learning is expe- so on. Projects can also involve simulated riential and negotiated learning, cooperative audiences made up of teacher and class- learning (through group and team work), mates. -

Movement of Natural Persons Between the Philippines and Japan: Issues and Prospects Tereso S

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Movement of Natural Persons Between the Philippines and Japan: Issues and Prospects Tereso S. Tullao Jr. and Michael Angelo A. Cortez DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2004-11 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. March 2004 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph List of Projects under the Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Research Project Title of the Project Proponent Impact analysis on the whole economy 1. Situationer on Japan-Philippines Economic Relations Erlinda Medalla 2. Philippine-Japan Bilateral Agreements: Analysis of Possible Caesar Cororaton Effects on Unemployment, Distribution and Poverty in the Philippines Using CGE-Microsimulation Approach Impact analysis on specific sectors/ concerns 3. An Analysis of Industry and Sector- Specific Impacts of a AIM Policy Center Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership (Royce Escolar) 4. -

The Chinese in Hawaii: an Annotated Bibliography

The Chinese in Hawaii AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY by NANCY FOON YOUNG Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii Hawaii Series No. 4 THE CHINESE IN HAWAII HAWAII SERIES No. 4 Other publications in the HAWAII SERIES No. 1 The Japanese in Hawaii: 1868-1967 A Bibliography of the First Hundred Years by Mitsugu Matsuda [out of print] No. 2 The Koreans in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Arthur L. Gardner No. 3 Culture and Behavior in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Judith Rubano No. 5 The Japanese in Hawaii by Mitsugu Matsuda A Bibliography of Japanese Americans, revised by Dennis M. O g a w a with Jerry Y. Fujioka [forthcoming] T H E CHINESE IN HAWAII An Annotated Bibliography by N A N C Y F O O N Y O U N G supported by the HAWAII CHINESE HISTORY CENTER Social Science Research Institute • University of Hawaii • Honolulu • Hawaii Cover design by Bruce T. Erickson Kuan Yin Temple, 170 N. Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu Distributed by: The University Press of Hawaii 535 Ward Avenue Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 International Standard Book Number: 0-8248-0265-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-620231 Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Copyright 1973 by the Social Science Research Institute All rights reserved. Published 1973 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi ABBREVIATIONS xii ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 GLOSSARY 135 INDEX 139 v FOREWORD Hawaiians of Chinese ancestry have made and are continuing to make a rich contribution to every aspect of life in the islands. -

O. Van Den Muijzenberg Philippine-Dutch Social Relations, 1600-2000 In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde, the Philip

O. van den Muijzenberg Philippine-Dutch social relations, 1600-2000 In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, The PhilippinesHistorical and social studies 157 (2001), no: 3, Leiden, 471-509 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 12:31:34PM via free access OTTO VAN DEN MUIJZENBERG Philippine-Dutch Social Relations 1600-2000 Few historians have focused their research on Dutch-Philippine, relations, and the few important exceptions - like N.A. Bootsma, Ruurdje Laarhoven, M.P.H. Roessingh and Fr. P. Schreurs, MSC - have confined themselves to small regions or periods. The recent commemoration of the first Dutch cir- cumnavigation of the globe by Olivier van Noort demonstrated the lack of an up-to-date overview of the ups and downs in Dutch-Philippine relations in the course of the past four centuries. This may not seem surprising, consider- ing the absence of a history of intense, continuous contact. The two sides started with a drawn-out contest, followed by nearly three centuries of little connection, and only fifty years of significant flows of trade, people, trans- port and information. The year 1600 was a remarkable one for the emerging Dutch nation, which had been fighting for its independence from Spain since 1568. A major battle was won at Nieuwpoort, while in Asia two small fleets ventured beyond Java, then newly 'discovered' by Cornelis de Houtman (1595-96). The expedition of the Liefde (Love) resulted in long-lasting trade relations with Japan, with the Dutch obtaining an import and export monopoly through their factory at Deshima. -

Mock Filipino, Hawai'i Creole, and Local Elitism

Pragmatics 21:3.341-371 (2011) International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.21.3.03hir IS DAT DOG YOU’RE EATING?: MOCK FILIPINO, HAWAI‘I CREOLE, AND LOCAL ELITISM Mie Hiramoto Abstract This paper explores both racial and socioeconomic classification through language use as a means of membership categorization among locals in Hawai‘i. Analysis of the data focuses on some of the most obvious representations of language ideology, namely, ethnic jokes and local vernacular. Ideological constructions concerning two types of Filipino populations, local Filipinos and immigrant Filipinos, the latter often derisively referred to as “Fresh off the Boat (FOB)” are performed differently in ethnic jokes by local Filipino comedians. Scholars report that the use of mock language often functions as a racialized categorization marker; however, observations on the use of Mock Filipino in this study suggest that the classification as local or immigrant goes beyond race, and that the differences between the two categories of Filipinos observed here are better represented in terms of social status. First generation Filipino immigrants established diaspora communities in Hawai‘i from the plantation time and they slowly merged with other groups in the area. As a result, the immigrants’ children integrated themselves into the local community; at this point, their children considered themselves to be members of this new homeland, newly established locals who no longer belonged to their ancestors’ country. Thus, the local population, though of the same race with the new immigrants, act as racists against people of their own race in the comedy performances. Keywords: Hawai‘i Creole; Mock Filipino; Stylization; Ethnic jokes; Mobility. -

2020 Bayanihan to Heal As One Act Accomplishment Report

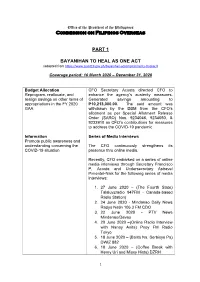

Office of the President of the Philippines Commission on Filipinos Overseas PART 1 BAYANIHAN TO HEAL AS ONE ACT (adopted from https://www.covid19.gov.ph/bayanihan-accomplishments-tracker/) Coverage period: 16 March 2020 – December 31, 2020 Budget Allocation CFO Secretary Acosta directed CFO to Reprogram, reallocate, and enhance the agency’s austerity measures. realign savings on other items of Generated savings amounting to appropriations in the FY 2020 P10,213,000.00. The said amount was GAA withdrawn by the DBM from the CFO’s allotment as per Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) Nos. 9234046, 9234050, & 9233910 as CFO’s contributions for measures to address the COVID-19 pandemic. Information Series of Media Interviews Promote public awareness and understanding concerning the The CFO continuously strengthens its COVID-19 situation presence thru online media. Recently, CFO embarked on a series of online media interviews through Secretary Francisco P. Acosta and Undersecretary Astravel Pimentel-Naik for the following series of media interviews: 1. 27 June 2020 – (The Fourth State) Talaluvzradio 947FM - Canada-based Radio Station) 2. 24 June 2020 - Mindanao Daily News Radyo Natin 106.3 FM CDO 3. 22 June 2020 - PTV News Mindanao/Davao 4. 20 June 2020 –(Online Radio Interview with Nanay Anita) Pnoy FM Radio Tokyo 5. 18 June 2020 – (Balita Na, Serbisyo Pa) DWIZ 882 6. 18 June 2020 – (Coffee Break with Henry Uri and Missy Hista) DZRH 1 7. 17 June 2020 –Oras na Pilipinas, 702 DZAS – FEBC Radio 8. 16 June 2020 – Teka, Alas 4;30 na DWIZ 882 9. 13 June 2020 – Kabayani Tallks of the Filipino Channel (TFC) 10. -

13 AUG -6 Am :31

SIXTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES First Regular Session 13 AUG -6 Am :31 SENATE S.B. No. 1215 Introduced by Senator Poe Explanatory Note This bill seeks to create the National Seafarers Administration to look into and protect the interests and welfare of Filipino seafarers. A National Seamen Board was created in 1974 to develop and maintain a comprehensive program for Filipino Seafarers employed overseas. However, the Board was abolished in 1982 with the creation of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration under Executive Order No. 797 which has been empowered to formulate and undertake a systematic program for promoting and monitoring the overseas' employment of Filipino workers. The body is likewise mandated to protect the rights of migrant workers including seamen so that they can have fair and enjoy equitable employment practices. An Advisory Board for Seamen was also created which was composed of private sector to advise the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration on its overseas operations. While many commend the performance of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration in protecting the rights and promoting the welfare of Filipino overseas workers, the overseas seamen continually claim that they have been overlooked by the government. The agency concerned may not be aware but the seafarers feel that they are not fully protected and their valid claims, not fully attended. The problems of these workers are so complicated that a government mechanism fully concentrating on the sea-based workers is necessary. This legislation is highlighted with the following good points: 1. The creation of a special body on Filipino seafarers. -

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc. -

An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 4-22-2011 Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940 Krista Baylon Sorenson Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Baylon Sorenson, Krista, "Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 98. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940 A Thesis Presented to the Department of History College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Krista Baylon Sorenson April 22, 2011 Sorenson 1 “Why was America so kind and yet so cruel? Was there no way to simplify things in this continent so that suffering would be minimized? Was there not common denominator on which we could all meet? I was angry and confused and wondered if I would ever understand this paradox?”1 “It was a planless life, hopeless, and without direction. I was merely living from day to day: yesterday seemed long ago and tomorrow was too far away. It was today that I lived for aimlessly, this hour-this moment.”2 -Carlos Bulosan, America is in the Heart Introduction Carlos Bulosan was a Filipino immigrant living in the United States beginning in the 1930s. -

CATALLA-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (3.265Mb)

KUWENTO/STORIES: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY OF FILIPINO AMERICAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE STUDENTS _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education _____________ by Pat Lindsay Carijutan Catalla May, 2019 KUWENTO/STORIES: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY OF FILIPINO AMERICAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE STUDENTS by Pat Lindsay Carijutan Catalla ______________ APPROVED: Paul William Eaton, PhD Dissertation Director Rebecca Bustamante, PhD Committee Member Ricardo Montelongo, PhD Committee Member Stacey Edmonson, PhD Dean, College of Education DEDICATION I dedicate this body of work to my family, ancestors, friends, colleagues, dissertation committee, Filipino American community, and my future self. I am deeply thankful for all the support each person has given me through the years in the doctoral program. This is a journey I will never, ever forget. iii ABSTRACT Catalla, Pat Lindsay Carijutan, Kuwento/Stories: A narrative inquiry of Filipino American Community College students. Doctor of Education (Education), May, 2019, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. The core of this narrative inquiry is the kuwento, story, of eight Filipino American community college students (FACCS) in the southern part of the United States. Clandinin and Connelly’s (2000) three-dimension inquiry space—inwards, outwards, backwards, and forwards—provided a space for the characters, Bunny, Geralt, Jay, Justin, Ramona, Rosalinda, Steve, and Vivienne, to reflect upon their educational, career, and life experiences as a Filipino American. The character’s stories are delivered in a long, uninterrupted kuwento, encouraging critical discourse around their Filipino American identity development and educational struggles as a minoritized student in higher education. -

Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929

Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Preliminary Guide to the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union Local 7 Records. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/CanneryWorkersandFarmLaborersUnionLocal7SeattleWash3927/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search CANNERY WORKERS' AND FARM LABORERS' UNION. LOCAL NO. 7 1998 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES MANUSCRIPTS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES CANNERY WORKERS' AND FARM LABORERS' UNION. LOCAL NO. 7 Accession No. 3927-001 GUIDE HISTORY The Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union was organized June 19, 1933 in Seattle to represent the primarily Filipino-American laborers who worked in the Alaska salmon canneries. Filipino Alaskeros first appeared in the canneries around 1911. In the 1920s as exclusionary immigration laws went into effect, they replaced the Japanese, who had replaced the Chinese in the canneries. Workers were recruited through labor contractors who were paid to provide a work crew for the summer canning season. The contractor paid workers wages and other expenses. This system led to many abuses and harsh working conditions from which grew the movement toward unionization. The CWFLU, under the leadership of its first President, Virgil Duyungan, was chartered as Local 19257 by the American Federation of Labor in 1933. On December 1, 1936 an agent of a labor contractor murdered Duyungan and Secretary Aurelio Simon.