Preservation Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth and Memory: the Legacy of the John Hancock House

MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Rebecca J. Bertrand All Rights Reserved MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand Approved: __________________________________________________________ Brock Jobe, M.A. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Every Massachusetts schoolchild walks Boston’s Freedom Trail and learns the story of the Hancock house. Its demolition served as a rallying cry for early preservationists and students of historic preservation study its importance. Having been both a Massachusetts schoolchild and student of historic preservation, this project has inspired and challenged me for the past nine months. To begin, I must thank those who came before me who studied the objects and legacy of the Hancock house. I am greatly indebted to the research efforts of Henry Ayling Phillips (1852- 1926) and Harriette Merrifield Forbes (1856-1951). Their research notes, at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts served as the launching point for this project. This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and guidance of my thesis adviser, Brock Jobe. -

City of Gloucester Community Preservation Committee

CITY OF GLOUCESTER COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE BUDGET FORM Project Name: Masonry and Palladian Window Preservation at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Applicant: Historic New England SOURCES OF FUNDING Source Amount Community Preservation Act Fund $10,000 (List other sources of funding) Private donations $4,000 Historic New England Contribution $4,000 Total Project Funding $18,000 PROJECT EXPENSES* Expense Amount Please indicate which expenses will be funded by CPA Funds: Masonry Preservation $13,000 CPA and Private donations Window Preservation $2,200 Historic New England Project Subtotal $15,200 Contingency @10% $1,520 Private donations and Historic New England Project Management $1,280 Historic New England Total Project Expenses $18,000 *Expenses Note: Masonry figure is based on a quote provided by a professional masonry company. Window figure is based on previous window preservation work done at Beauport by Historic New England’s Carpentry Crew. Historic New England Beauport, The Sleeper-McCann House CPA Narrative, Page 1 Masonry Wall and Palladian Window Repair Historic New England respectfully requests a $10,000 grant from the City of Gloucester Community Preservation Act to aid with an $18,000 project to conserve a portion of a masonry wall and a Palladian window at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, a National Historic Landmark. Project Narrative Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, was the summer home of one of America’s first professional interior designers, Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934). Sleeper began constructing Beauport in 1907 and expanded it repeatedly over the next twenty-seven years, working with Gloucester architect Halfdan M. -

David S. Gordon

David S. Gordon PUBLIC SERVICE Mayor, City of Newport 1996-2000 Newport City Council, at-large member 1994-96 Newport Public Library, Board of Trustees 1993-96; 1997-2005, 2010-16 Friends of the Library, Executive Committee 1988-93; Treasurer 1988-90; President 1990-91 Department of the Navy Meritorious Public Service Award 2016 Naval War College Foundation, Trustee 2009-15, Vice Chair 2012-15 Newport Hospital, Trustee 2008-12; Newport Hospital Foundation, Vice Chair 2013-16, Secretary 2017- Newport County Fund, Rhode Island Foundation, Board of Advisors 2006-11 Gateway Design Review Committee, Chairman 2000-02 Newport Historical Society, Board of Directors 1999-02 Comprehensive Land Use Plan for the City of Newport, Citizens' Advisory Committee, Economic Development Subcommittee, Chairman 1989-93 Fort Adams Foundation, Board of Trustees 1993-2005; President’s Award for Outstanding Service 2004 Newport Art Museum, Treasurer, Board of Trustees 1989-92 Newport Restoration Foundation, Board of Trustees 2002-18 Preservation Society of Newport County, Board of Trustees 2002-08 Child and Family Services of Newport County, Board of Directors 2004-07 Stanford White Casino Theatre, Restoration Committee 2006-11 Newport County NAACP Branch Community Service Award 1999 EDUCATION INVOLVEMENT Newport School Committee 2002-05; Chairman 2002-03, 2004-05 Newport Public Schools Strategic Plan, Planning Team 1996-2001, Action Team 2001-03 Thompson Middle School Capital Campaign, Co-chairman 2000-02 University of Rochester, New England Regional Cabinet -

FORM a - AREA See Data Wilmington TEW.A, See Data Sheet E Sheet

Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area FORM A - AREA See Data Wilmington TEW.A, See Data Sheet E Sheet MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Town/City: Tewksbury Photograph Place (neighborhood or village): Tewksbury Centre Name of Area: Tewksbury Centre Area Present Use: Mixed use Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1737–2016 Overall Condition: Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: Vinyl siding and windows, spot demolition leaving vacant lots, late 20th c. Acreage: 57.5ac Photo 1. 60 East Street, looking northwest. Recorded by: V. Adams, G. Pineo, J. Chin, E. Totten, PAL Organization: Tewksbury Historical Commission Date (month/year): March 2020 Locus Map ☐ see continuation sheet 4/11 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET TEWKSBURY TEWKSBURY CENTRE AREA MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 TEW.A, E See Data Sheet ☒ Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Tewksbury Centre Area (TEW.A), the civic and geographic heart of Tewksbury, encompasses approximately 58 buildings across 57.5 acres centered on the Tewksbury Common at the intersection of East, Pleasant, and Main streets and Town Hall Avenue. Tewksbury Centre has a concentration of civic, institutional, commercial, and residential buildings from as early as ca. 1737 through the late twentieth century; mid-twentieth-century construction is generally along smaller side streets on the outskirts of the Tewksbury Centre Area. -

City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan

Updated 1/13/10 hk Version 4.4 City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan The Newport Waterfront Commission Prepared by the Harbor Management Plan Committee (A subcommittee of the Newport Waterfront Commission) Version 1 “November 2001” -Is the original HMP as presented by the HMP Committee Version 2 “January 2003” -Is the original HMP after review by the Newport . Waterfront Commission with the inclusion of their Appendix K - Additions/Subtractions/Corrections and first CRMC Recommended Additions/Subtractions/Corrections (inclusion of App. K not 100% complete) -This copy adopted by the Newport City Council -This copy received first “Consistency” review by CRMC Version 3.0 “April 2005” -This copy is being reworked for clerical errors, discrepancies, and responses to CRMC‟s review 3.1 -Proofreading – done through page 100 (NG) - Inclusion of NWC Appendix K – completely done (NG) -Inclusion of CRMC comments at Appendix K- only “Boardwalks” not done (NG) 3.2 -Work in progress per CRMC‟s “Consistency . Determination Checklist” : From 10/03/05 meeting with K. Cute : From 12/13/05 meeting with K. Cute 3.3 -Updated Approx. J. – Hurricane Preparedness as recommend by K. Cute (HK Feb 06) 1/27/07 3.4 - Made changes from 3.3 : -Comments and suggestions from Kevin Cute -Corrects a few format errors -This version is eliminates correction notations -1 Dec 07 Hank Kniskern 3.5 -2 March 08 revisions made by Hank Kniskern and suggested Kevin Cute of CRMC. Full concurrence. -Only appendix charts and DEM water quality need update. Added Natural -

Building Order on Beacon Hill, 1790-1850

BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Spring 2016 © 2016 Jeffrey Eugene Klee All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 10157856 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10157856 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Lawrence Nees, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Art History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Bernard L. Herman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

HISTORIC RESOURCES CHAPTER 2015 REGIONAL MASTER PLAN for the Rockingham Planning Commission Region

HISTORIC RESOURCES CHAPTER 2015 REGIONAL MASTER PLAN For the Rockingham Planning Commission Region Rockingham Planning Commission Regional Master Plan Historical Resources C ONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 What the Region Said About Historical Resources ............................................................................ 2 Historical Resources Goals ............................................................................................................... 3 Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................................... 5 Historical Background and Resources in the RPC Region....................................................................... 5 Preservation Tools .......................................................................................................................... 9 Key Issues and Challenges ............................................................................................................. 18 What Do We Preserve? ................................................................................................................. 18 Education and Awareness .............................................................................................................. 19 Redevelopment, Densification, and Tear-Downs ................................................................................ 20 -

Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan 2016 Update

City of Newport, Rhode Island Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan 2016 Update FEMA approval date January 5, 2017 Prepared for The City of Newport 43 Broadway Newport, RI 02840 Prepared by 1 Cedar St, Suite 400 Providence, RI 02903 City of Newport 2016 Hazard Mitigation Committee City of Newport, Department Zoning and Inspections Guy E. Weston, Zoning Officer William A. Hanley, II, Building Official City of Newport, Department Zoning and Inspections, Planning Division Christine A. O’Grady, City Planner Helen Johnson, Preservation Planner City of Newport, Fire Department Peter Connerton, Chief & Emergency Management Director City of Newport, Police Department Gary Silva, Chief City of Newport, Department of Public Services William Riccio, Director City of Newport, Department of Utilities Julia Forgue, Director Newport Hospital, Director of Emergency Preparedness (Health Care Representative) Pamela Mace, Director of Emergency Preparedness Coast Guard – Castle Hill Station John Roberts, Commanding Officer Karl Anderson, Executive Petty Officer Environmental Representative – Coastal Resources Center at the University of Rhode Island Teresa Crean, Coastal Manager Community Representative Frank Ray, Esq. Utility Representative – National Grid Jacques Afonso, Prin Program Manager City Manager Joseph J. Nicholson, Jr., Esq. Acting City Solicitor Christopher J. Behan City of Newport 2013 Hazard Mitigation Committee City of Newport, Department of Civic Investment Paul Carroll, Director Melissa Barker, GIS City of Newport, Fire Department Peter Connerton, -

Map 1A - Newburyport, Newbury, Rowley - Skirting the End of the Airport's Grassy Runway BAY CIRCUIT TRAIL Route (CAUTION: This Is an Active Runway

Disclaimer and Cautions: The Bay Circuit Alliance, as the advocate and promoter of the Bay Circuit Trail, expressly disclaims responsibility for injuries or damages that may arise from using the trail. We cannot guarantee the accuracy of maps or completeness of warnings about hazards that may exist. Portions of the trail are along roads or train tracks and involve crossing them. Users should pay attention to traffic and walk on the shoulder of roads facing traffic, not on the pavement, cross only at designated locations and use extreme care. Children and pets need to be closely monitored and under control. Refuge headquarters across the road. The BCT continues from the south side of the road just at the end of the Plum Island airport (an historic site). A signboard here usually has brochures about the BCT in Newbury. Proceed south on the Eliza Little Trail , Map 1A - Newburyport, Newbury, Rowley - skirting the end of the airport's grassy runway BAY CIRCUIT TRAIL route (CAUTION: this is an active runway. Keep to the (as shown on map dated March 2013) edge and keep dogs on leash ). Then go right on a (text updated May 2014) cart rd through high grass and through the fields of the Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm (bicycles not The BCT often follows pre-existing local trails; BCT- allowed). specific blazing is a work in progress and may be sparse 2.5 Pass through a gate south (left) of the historic in segments. We encourage you to review and carry Spencer-Peirce-Little Manor House , open to the corresponding local maps on your BCT walk. -

Volume 10 Issue 1 Winter 2009

The Phillips Scholar The Stephen Phillips Memorial Scholarship Fund Volume 10 Issue 1 Winter 2009 The Stephen Phillips Memorial Scholarship places great emphasis on service to others in selecting recipients, and we are gratifi ed that Phillips Scholars continue to be standouts in their college years and beyond. In this issue, we write about Scholars who are giving back in a variety of ways and hope that you fi nd inspiration to continue your service to others in reading about their efforts. The Stephen Phillips Memorial Scholarship Fund The fl ooding of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina has been followed by an P.O. Box 870 unprecedented flood of volunteerism to the devastated city, and many Phillips Schol- 27 Flint Street ars have strapped on tool belts and forgone their vaca- Salem, Massachusetts 01970 tions to go help. For Emma Stenberg, it was a “life-alter- 978-744-2111 www.phillips-scholarship.org ing trip” with her classmates from St. Michael’s College, and she feels “fortunate to have played even the small- Trustees est part in renewing hope” for the residents there. She Arthur Emery expresses the single most common theme from the essays Managing Trustee scholars have written about their experiences: “After gut- ting, rewiring and restructuring a house, my team and I Lawrence Coolidge emerged with new lessons about service, compassion and John Finley, IV faith.” Richard Gross Latoya Ogunbona’s group from North Shore Communi- ty College (MA) assisted a family whose losses stemmed Robert Randolph Emma Stenberg hammering from the flooding and then, in a dishearteningly com- away on her fi rst Gulf coast mon event, from a contractor who stole $70,000 worth trip. -

Johnston Historical Society Historical Notes

# Johnston Historical Society Historical Notes Vol. XXIII, #2 Christopher Martin, Editor Louis McGowan, Assistant August 2017 www.JohnstonHistorical.org Historical Notes by Mabel (Atwood) Sprague "The fields on the opposite side of the road were all open until [The following historical piece was written by Mabel (Atwood) you came to the old Davis farm. The house still stands but has Sprague, who lived most of her life on Morgan Avenue. The been made over some. The barns & the other buildings are gone, piece is undated (written between 1967 and 1982; she writes in a large slaughter house [?] was down by the river. A large barn this piece that she and her sister are the only family members by the side of the road was made into a tenement house & that is left. Her sister Alice died in 1967 and her other sister Blanche still standing. When I was young a family by the name of [?] died in 1982), and was hand-written. I have transcribed her notes George Ducharme lived there. He was chief of police in Johnston from the original as accurately as I could. (LHM)] at the same time my father (Edmund Clark Atwood) was town sergeant, this was about the turn of the century (1900). "Things that have been told to me & some things I remember about this locality of Johnston, R.I. "Starting at the Johnston-Providence City line was the King Homestead with a very large house & barn & other buildings which were very old but very well kept. Mr. King's farm was large & it went up on to Neutaconkanut Hill. -

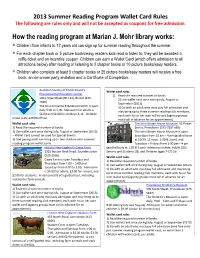

How the Reading Program at Marian J. Mohr Library Works: ∗ Children from Infants to 12 Years Old Can Sign up for Summer Reading Throughout the Summer

2013 Summer Reading Program Wallet Card Rules The following are rules only and will not be accepted as coupons for free admission. How the reading program at Marian J. Mohr library works: ∗ Children from infants to 12 years old can sign up for summer reading throughout the summer. ∗ For each chapter book or 5 picture books/easy readers kids read or listen to, they will be awarded a raffle ticket and an incentive coupon. Children can earn a Wallet Card (which offers admission to all attractions below) after reading or listening to 2 chapter books or 10 picture books/easy readers. ∗ Children who complete at least 5 chapter books or 25 picture books/easy readers will receive a free book, an ice cream party invitation and a Certificate of Completion. Audubon Society of Rhode Island's Wallet card rules Environmental Education Center 1) Read the required number of books 1401 Hope Street (Rt.114), Bristol (245- 2) Use wallet card once during July, August or 7500) September (2013) The Environmental Education Center is open 3) Go with an adult who must pay full admission and daily 9:00 to 5:00. Admission for adults is may bring up to three summer reading club members, $6.00 and $4.00 for children 4-12. Children each with his or her own wallet card (agency groups under 4 are admitted free. must call in advance for an appointment) Wallet card rules The John Brown House Museum 52 Power 1) Read the required number of books Street, Providence (273-7507 x60) 2) Use wallet card once during July, August or September (2013) The John Brown House Museum is open – Wallet Card cannot be used for Special Events.