Cancer Facts & Figures 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021

Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021 Estimated Numbers of Cancer Survivors by State as of January 1, 2019 WA 386,540 NH MT VT 84,080 ME ND 95,540 59,970 38,430 34,360 OR MN 213,620 300,980 MA ID 434,230 77,860 SD WI NY 42,810 313,370 1,105,550 WY MI 33,310 RI 570,760 67,900 IA PA NE CT 243,410 NV 185,720 771,120 108,500 OH 132,950 NJ 543,190 UT IL IN 581,350 115,840 651,810 296,940 DE 55,460 CA CO WV 225,470 1,888,480 KS 117,070 VA MO MD 275,420 151,950 408,060 300,200 KY 254,780 DC 18,750 NC TN 470,120 AZ OK 326,530 NM 207,260 AR 392,530 111,620 SC 143,320 280,890 GA AL MS 446,900 135,260 244,320 TX 1,140,170 LA 232,100 AK 36,550 FL 1,482,090 US 16,920,370 HI 84,960 States estimates do not sum to US total due to rounding. Source: Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. Contents Introduction 1 Long-term Survivorship 24 Who Are Cancer Survivors? 1 Quality of Life 24 How Many People Have a History of Cancer? 2 Financial Hardship among Cancer Survivors 26 Cancer Treatment and Common Side Effects 4 Regaining and Improving Health through Healthy Behaviors 26 Cancer Survival and Access to Care 5 Concerns of Caregivers and Families 28 Selected Cancers 6 The Future of Cancer Survivorship in Breast (Female) 6 the United States 28 Cancers in Children and Adolescents 9 The American Cancer Society 30 Colon and Rectum 10 How the American Cancer Society Saves Lives 30 Leukemia and Lymphoma 12 Research 34 Lung and Bronchus 15 Advocacy 34 Melanoma of the Skin 16 Prostate 16 Sources of Statistics 36 Testis 17 References 37 Thyroid 19 Acknowledgments 45 Urinary Bladder 19 Uterine Corpus 21 Navigating the Cancer Experience: Treatment and Supportive Care 22 Making Decisions about Cancer Care 22 Cancer Rehabilitation 22 Psychosocial Care 23 Palliative Care 23 Transitioning to Long-term Survivorship 23 This publication attempts to summarize current scientific information about Global Headquarters: American Cancer Society Inc. -

PATHOLOGY, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences A

FORMAT FOR SUBJECTWISE IDENTIFYING JOURNALS BY THE UNIVERSITIES AND APPROVAL OF THE UGC {Under Clause 6.05 (1) of the University Grants Commission (Minimum Qualifications for appointment of Teacher and Other Academic Staff in Universities and Colleges and Measures for the Maintenance of Standards in Higher Education (4th Amendment), Regulations, 2016} Subject: PATHOLOGY, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences A. Refereed Journals Sl. Name of the Journal Publisher and Year of Hard e-publication ISSN Number Peer / Indexing status. Impact Do you use Any other No. place of Start copies (Yes/No) Refree If indexed, Factor/Rating. any Information publication published Reviewed Name of the Name of the IF exclusion (Yes/No) (Yes/No) indexing data assigning agency. criteria for base Whether covered Research by Thompson & Journals Reuter (Yes/No) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 Acta cytologica Karger, Basel 1957 Yes Yes 0001-5547(Print); Yes Indexed (Index 1.562 (Impact (Switzerland) 1938- medicus, Medline, Factor by Thomson 2650(Electronic); Pubmed) Reuters) 0001-5547(Linking) 2 Acta oncologica Informa Healthcare, 1987 No Yes 0284-186X(Print); Yes Indexed (Index 3.730 (Impact London (England) 1651- medicus, Medline, Factor by Thomson 226X(Electronic); Pubmed) Reuters) 0284-186X(Linking) 3 Advances in anatomic pathology Lippincott Williams 1994 Yes Yes 1072-4109(Print); Yes Indexed (Index 2.919 (Impact & Wilkins, 1533- medicus, Medline, Factor by Thomson Hagerstown, MD 4031(Electronic); Pubmed) Reuters) 1072-4109(Linking) 4 American journal of clinical oncology Lippincott Williams 1982 Yes Yes 0277-3732(Print); Yes Indexed (Index 2.977 (Impact & Wilkins, 1537- medicus, Medline, Factor by Thomson Hagerstown, MD 453X(Electronic); Pubmed) Reuters) 0277-3732(Linking) Sl. -

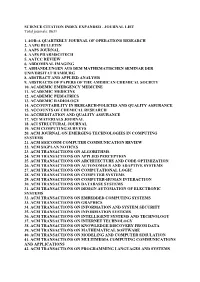

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Vigilância Sanitária em Debate ISSN: 2317-269X INCQS-FIOCRUZ Souza, Diego de Oliveira A saúde dos trabalhadores e a pandemia de COVID-19: da revisão à crítica Vigilância Sanitária em Debate, vol. 8, no. 3, 2020, July-September, pp. 125-131 INCQS-FIOCRUZ DOI: https://doi.org/10.22239/2317-269X.01627 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=570566811014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative REVIEW https://doi.org/10.22239/2317-269x.01627 The health of workers and COVID-19 pandemic: from review to criticism A saúde dos trabalhadores e a pandemia de COVID-19: da revisão à crítica ABSTRACT Diego de Oliveira Souza* Introduction: With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, science needs to give quick answers. The context has been violent, especially for workers. Objective: critically summarize the main scientific recommendations for workers in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Method: This is a literature review from PubMed e VHL, in which 19 publications were obtained for analysis. Results: In the literature, emphasis was placed on the issue of PPE, hygiene measures and other individual measures. Some studies address organizational issues and surveillance for healthcare workers, but also for workers in general. Conclusions: In addition to the synthesis of publications, the review contributes with reflections and provocations with a view to further interventions. KEYWORDS: Coronavirus; Pandemics; Occupational Health; Work RESUMO Introdução: Em meio a um contexto atípico, com a emergência da pandemia de COVID-19, a ciência precisa dar respostas na mesma velocidade da propagação do SARS-CoV-2. -

Cancer Cytopathology

Session 1.3: Editorial and Publishing Questions - Data Informed Solutions • Jill Jackson, Manuscript Processing & Publishing Administrator, American College of Physicians • Esmeralda Buchanan, Senior Director, Journals and Books Publishing, American Cancer Society • Brittany Gerig Campbell, Marketing Manager, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences • Kerry Kroffe, Senior Editorial Manager, PLOS • Jeanette Panning, Assistant Director, Publications Programs, American Geophysical Union • Sarah Tegen, PhD, Vice President, Global Editorial & Author Services, American Chemical Society Are My Users My Customers? CSE 2016 Annual Meeting May 16, 2016 Jill Jackson Manuscript Processing/Publishing Administrator American College of Physicians [email protected] Annals of Internal Medicine . Premier internal medicine journal . Readership includes the 143,000 members of the American College of Physicians and many more physicians and researchers worldwide . One of the most highly cited and influential journals in the world 3 Back in the day … Users/Customers 100% 4 Today 5 Annals of Internal Medicine Average Usage Customer, 40% User, 60% 6 Users . Anyone who comes to our site . They are usually the larger part of the audience, but not necessarily our intended audience 7 Who Are My Users? . Physicians/Clinicians/Allied Health Professionals . Researchers . Media . Advertisers . Medical/Scientific Societies, Funding and Advocacy Groups (e.g., PCORI) . Organizations (pharmaceutical companies, law firms) . Public 8 Importance High usage produces: . Higher sales . More exposure to other products on our web site . Data about popular articles . Awareness of quality, carefully vetted information 9 Customers . People who pay for our content . Identifiable information (demographics) 10 Who Are My Customers? . Members of American College of Physicians (ACP) . Individual Subscribers . Institutional Subscriptions . -

Cancer Facts and Figures 2016

Cancer Facts & Figures 2016 WA 37,770 NH MT 8,680 ME ND VT 6,070 9,270 3,930 MN 4,050 OR 29,130 22,510 MA ID 37,620 8,120 SD WI NY 4,690 32,970 WY 110,280 MI RI 2,920 56,530 6,190 IA PA NV NE 17,100 83,560 CT 21,700 14,390 9,740 OH NJ 49,750 UT IL IN 66,020 65,090 35,180 DE 5,630 CA 11,030 CO WV 173,200 24,730 VA KS MO 11,770 MD 30,990 KY 43,190 14,530 34,270 DC 2,910 25,720 NC TN 54,450 AZ OK 37,650 32,510 NM 19,650 AR SC 9,750 16,460 27,980 MS AL GA 16,680 27,020 48,670 TX 116,690 LA 25,070 AK 3,330 FL 121,240 US 1,685,210 PR HI N/A 6,850 Estimated numbers of new cancer cases for 2016, excluding basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers and in situ carcinomas except urinary bladder. Estimates are not available for Puerto Rico. Note: State estimates are offered as a rough guide and should be interpreted with caution. State estimates may not add to US total due to rounding. Special Section: Cancer in Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders see page 25 Contents Basic Cancer Facts 1 Figure 1. Trends in Age-adjusted Cancer Death Rates by Site, Males, US, 1930-2012 2 Figure 2. Trends in Age-adjusted Cancer Death Rates by Site, Females, US, 1930-2012 3 Table 1. -

0060.37 ACS 100 Years Timeline PFLO-2.Indd

HELPING SAVE LIVES FROM CANCER 1913 The American Cancer Society is founded. Fift een physicians 1936 and businessmen in New York City, who were determined to raise Women make noise to help save lives. A group of passionate awareness about cancer, form the American Society for the Control women form the Women’s Field Army – an organization of women of Cancer, later renamed the American Cancer Society. who took to the streets to educate people about cancer and raise money to help save lives. Their contributions were monumental in 1946 building the American Cancer Society and the cancer movement. The American Cancer Society launches our groundbreaking research program. Philanthropist 1948 Mary Lasker and her colleagues revolutionize the organization’s The American Cancer Society pushes for wide mission and fundraising eff orts, helping to raise more than $4 million – adoption of the Pap test. Cervical cancer death rates have $1 million of which was used to establish the program. declined by more than 70 percent, largely due to widespread uptake of the Pap test in the latter half of the 20th century. 1950 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians begins publication. The first issue of Cancer, a peer-reviewed oncology journal, Visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/caac.v1:1/issuetoc is published. Visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1097- to see the first issue. 0142(194805)1:1%3C%3E1.0.CO;2-G/issuetoc to see the first issue. 1954 1952 The movement to stop smoking and reduce lung cancer begins. Cancer Facts & Figures begins publication. -

Peer-Reviewed Cytopathology Journals Are Important Resource for Practitioners in Many Medical Specialties

Central Annals of Clinical Cytology and Pathology Short Communication *Corresponding author Khalid Al Aboud, Department of laboratory, King Faisal Hospital, P.O Box 5440, Makah 21955, Saudi Arabia, Peer-Reviewed Cytopathology Submitted: 30 July 2015 Journals; a Tabulation Accepted: 23 October 2015 Published: 25 October 2015 Copyright Overview © 2015 Al Aboud et al. Khalid Al Aboud*, Nassir Idris, Rana Al Zaaidi, Alaa Moriani OPEN ACCESS Abdullah Halwani, Mohammad Al Joaid and Ghazwa Al Githami Keywords Department of laboratory, King Faisal Hospital, Saudi-Arabia • Cytopathology • Journal Abstract • Periodicals Peer-reviewed cytopathology journals are important resource for practitioners in many medical specialties. This report shed some light on the current peer-reviewed periodicals in cytopathology. INTRODUCTION There are several differences between Peer-reviewed journals in cytopathology. These include for example, the sponsoring Cytopathology is a discipline of medical sciences that studies society, the frequency of publication and the language. and diagnoses diseases on the cellular level. It is frequently, less Cytopathology periodicals make a major contribution to the development of this branch of pathology [1-3]. Continuing Medical Education (CME) and they are essential precisely, called cytology. Historically, many factors influenced reading for every practicing cytopathologist and cytotechnologist There are several national and international professional who wishes to keep abreast of new developments in this rapidly societies in cytopathology. There are increasing numbers of training programs in this branch of pathology. In an earlier study, it has shown that , there are 90 Accreditation Council for developingReadership field. of cytopthology periodicals also include Graduate Medical Education-accredited cytopathology fellowship training programs in the United States, each with its own unique and Endocrinologists. -

Source Publication List for Web of Science

SOURCE PUBLICATION LIST FOR WEB OF SCIENCE SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED Updated July 2017 Journal Title Publisher ISSN E-ISSN Country Language 2D Materials IOP PUBLISHING LTD 2053-1583 2053-1583 ENGLAND English 3 Biotech SPRINGER HEIDELBERG 2190-572X 2190-5738 GERMANY English 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing MARY ANN LIEBERT, INC 2329-7662 2329-7670 UNITED STATES English 4OR-A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research SPRINGER HEIDELBERG 1619-4500 1614-2411 GERMANY English AAPG BULLETIN AMER ASSOC PETROLEUM GEOLOGIST 0149-1423 1558-9153 UNITED STATES English AAPS Journal SPRINGER 1550-7416 1550-7416 UNITED STATES English AAPS PHARMSCITECH SPRINGER 1530-9932 1530-9932 UNITED STATES English AATCC Journal of Research AMER ASSOC TEXTILE CHEMISTS COLORISTS-AATCC 2330-5517 2330-5517 UNITED STATES English AATCC REVIEW AMER ASSOC TEXTILE CHEMISTS COLORISTS-AATCC 1532-8813 1532-8813 UNITED STATES English Abdominal Radiology SPRINGER 2366-004X 2366-0058 UNITED STATES English ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG SPRINGER HEIDELBERG 0025-5858 1865-8784 GERMANY German ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY AMER CHEMICAL SOC 0065-7727 UNITED STATES English Academic Pediatrics ELSEVIER SCIENCE INC 1876-2859 1876-2867 UNITED STATES English Accountability in Research-Policies and Quality Assurance TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD 0898-9621 1545-5815 UNITED STATES English Acoustics Australia SPRINGER 1839-2571 1839-2571 AUSTRALIA English Acta Bioethica UNIV CHILE, CENTRO INTERDISCIPLINARIO ESTUDIOS BIOETICA 1726-569X -

Title: a Critical Appraisal of Predatory Journals in Pathology

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/482174; this version posted December 4, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title: 2 A Critical Appraisal of Predatory Journals in Pathology 3 4 Yaman M. AlAhmad1#, Ibrahim Abdelhafez1#, Farhan S. Cyprian1, Faruk Skenderi2, 5 Saghir Akhtar1, Semir Vranic1* 6 7 1 College of Medicine, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar 8 2 Department of Pathology, Clinical Center, University of Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and 9 Herzegovina 10 # These authors contributed equally 11 12 13 *Correspondence: 14 Semir Vranic, MD, PhD 15 College of Medicine, Qatar University 16 2713 Doha, Qatar 17 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] 18 Phone: +974 4403 7873 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/482174; this version posted December 4, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 19 Abstract 20 Predatory or pseudo journals have recently come into focus due to their massive 21 internet expansion and extensive spam email soliciting. Recent studies explored this 22 urging problem in several biomedical disciplines. In the present study, we identified 69 23 potential predatory (pseudo) pathology journals that were contrasted to 89 legitimate 24 pathology journals obtained from the major bibliographic databases. -

American Cancer Society Information & Resources

AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY INFORMATION & RESOURCES Patient Information & Resources . Cancer Prevention and Early Detection ACS Guidelines http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w Downloadable PDF on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention ebcontent/002577-pdf.pdf http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w Lung Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Downloadable PDF ebcontent/acspc-039558-pdf.pdf http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w Prostate Cancer Early Detection Downloadable PDF ebcontent/003182-pdf.pdf English: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w ebcontent/003165-pdf.pdf Breast Cancer Early Detection Spanish: Downloadable PDFs http://www.cancer.org/espanol/cancer/cancerdeseno /recursosadicionales/fragmentado/cancer-de-seno- deteccion-temprana-importance-of-e-d English: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w ebcontent/003167-pdf.pdf Spanish: Cervical Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Downloadable PDFs http://www.cancer.org/espanol/cancer/cancerdecuell outerino/recursosadicionales/fragmentado/cancer-de- cuello-uterino-prevencion-y-deteccion-temprana- what-is-cervical-cancer English: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w ebcontent/003170-pdf.pdf Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Spanish: Downloadable PDFs http://www.cancer.org/espanol/cancer/colonyrecto/r ecursosadicionales/fragmentado/deteccion-temprana- del-cancer-colorrectal-what-is-c-r-c http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/w Mammograms and Other Breast Imaging Tests Downloadable PDF -

Complimentary Access to Selected Wiley Journals for Cochrane Review Groups

Complimentary access to selected Wiley journals 1 Complimentary access to selected Wiley journals for Cochrane Review Groups Date: July 2019 List of journals: No. Journal title 1 Academic Emergency Medicine 2 ACEP Now 3 Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 4 Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 5 Acta Neuropsychiatrica 6 Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 7 Acta Ophthalmalogica Scandinavica 8 Acta Paediatrica 9 Acta Physiologica 10 Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 11 Addiction 12 Addiction Biology 13 Alcoholism 14 Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 15 Allergy 16 American Journal of Hematology 17 American Journal of Industrial Medicine 18 American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 19 American Journal of Transplantation 20 American Journal on Addictions 21 An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 22 Anaesthesia 23 Anatomia Histologia and Embryologia 24 Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia 25 Andrologia 26 Annals of Neurology 27 Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology 28 ANZ Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 29 ANZ Journal of Surgery 30 APMIS 31 Archives of Drug Information 32 Arthritis & Rheumatism 33 Arthritis Care & Research 34 Artificial Organs Complimentary access to selected Wiley journals 2 35 Asian Journal of Endoscopic Surgery 36 Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 37 Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 38 Australasian Journal of Dermatology 39 Australasian Journal on Ageing 40 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 41 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 42 Australian Dental