Terrestrial Ecosystems Assessment of Proposed Ash Dump Sites at Kusile Power Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mantodea (Insecta), with a Review of Aspects of Functional Morphology and Biology

aua o ew eaa Ramsay, G. W. 1990: Mantodea (Insecta), with a review of aspects of functional morphology and biology. Fauna of New Zealand 19, 96 pp. Editorial Advisory Group (aoimes mae o a oaioa asis MEMBERS AT DSIR PLANT PROTECTION Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag Aucka ew eaa Ex officio ieco — M ogwo eae Sysemaics Gou — M S ugae Co-opted from within Systematics Group Dr B. A ooway Κ Cosy UIESIIES EESEAIE R. M. Emeso Eomoogy eame ico Uiesiy Caeuy ew eaa MUSEUMS EESEAIE M R. L. ama aua isoy Ui aioa Museum o iae ag Weigo ew eaa OESEAS REPRESENTATIVE J. F. awece CSIO iisio o Eomoogy GO o 1700, Caea Ciy AC 2601, Ausaia Series Editor M C ua Sysemaics Gou SI a oecio Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag Aucka ew eaa aua o ew eaa Number 19 Maoea (Iseca wi a eiew o asecs o ucioa mooogy a ioogy G W Ramsay SI a oecio M Ae eseac Cee iae ag Aucka ew eaa emoa us wig mooogy eosigma cooaio siuaio acousic sesiiiy eece eaiou egeeaio eaio aasiism aoogy a ie Caaoguig-i-uicaio ciaio AMSAY GW Maoea (Iseca – Weigo SI uisig 199 (aua o ew eaa ISS 111-533 ; o 19 IS -77-51-1 I ie II Seies UC 59575(931 Date of publication: see cover of subsequent numbers Suggese om o ciaio amsay GW 199 Maoea (Iseca wi a eiew o asecs o ucioa mooogy a ioogy Fauna of New Zealand [no.] 19. —— Fauna o New Zealand is eae o uicaio y e Seies Eio usig comue- ase e ocessig ayou a ase ie ecoogy e Eioia Aisoy Gou a e Seies Eio ackowege e oowig co-oeaio SI UISIG awco – sueisio o oucio a isiuio M C Maews – assisace wi oucio a makeig Ms A Wig – assisace wi uiciy a isiuio MOU AE ESEAC CEE SI Miss M oy -

The Genus Metallyticus Reviewed (Insecta: Mantodea)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228623877 The genus Metallyticus reviewed (Insecta: Mantodea) Article · September 2008 CITATIONS READS 11 353 1 author: Frank Wieland Pfalzmuseum für Naturkunde - POLLICHIA-… 33 PUBLICATIONS 113 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Frank Wieland letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 24 October 2016 Species, Phylogeny and Evolution 1, 3 (30.9.2008): 147-170. The genus Metallyticus reviewed (Insecta: Mantodea) Frank Wieland Johann-Friedrich-Blumenbach-Institut für Zoologie & Anthropologie und Zoologisches Museum der Georg-August-Universität, Abteilung für Morphologie, Systematik und Evolutionsbiologie, Berliner Str. 28, 37073 Göttingen, Germany [[email protected]] Abstract Metallyticus Westwood, 1835 (Insecta: Dictyoptera: Mantodea) is one of the most fascinating praying mantids but little is known of its biology. Several morphological traits are plesiomorphic, such as the short prothorax, characters of the wing venation and possibly also the lack of discoidal spines on the fore femora. On the other hand, Metallyticus has autapomor- phies which are unique among extant Mantodea, such as the iridescent bluish-green body coloration and the enlargement of the first posteroventral spine of the fore femora. The present publication reviews our knowledge of Metallyticus thus providing a basis for further research. Data on 115 Metallyticus specimens are gathered and interpreted. The Latin original descriptions of the five Metallyticus species known to date, as well as additional descriptions and a key to species level that were originally published by Giglio-Tos (1927) in French, are translated into English. -

Survey of the Superorder Sanghar, Sin Superorder

UNIVERSITY OF SINDH JOURNAL OF ANIMAL SCIENCES Vol. 2, Issue 1, pp: (19-23), April, 2018 Email: [email protected] ISSN(E) : 252 3-6067 Website: http://sujo.usindh.edu.pk/index.php/USJAS ISSN(P) : 2521-8328 © Published by University of Sindh, Jamshoro SURVEY OF THE SUPERORDER DICTYOPTERA MANTODEA FROM SANGHAR, SINDH , PAKISTAN Sadaf Fatimah, Riffat Sultana and Muhammad Saeed Wagan Department of Zoology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Article History: This paper deals with the fauna of different species of Mantodea from Received: 20 th December, 2017 Accepted: 10th April, 2018 different localities of Sanghar (district). A tota l of 16 species from 12 Published online: 15 th May, 2018 genera including (Blepharopsis, Empusa, Humbertiella, Deiphobe, Authors Contribution Archimantis, Hierodula, Mantis, Stalilia, Polyspilota, Iris , Rivetina and S.F collected the material and analyzed Eremphilia belong to 05 families Mantidae, Tarachodidae, Empusidae, the samples, R.S planned the study, and liturgusidae and Eremiaphilidae) were identified and presented. A M.S.W identified the material and finalized the result. All the authors read comparison of Pakistani Mantodea’s fauna at global level was also done and approved the final version of the and six new regional record species were also found and presented here. article. During this study significant numbers were captured. It was also noticed Key words: that its predatory behavior has very important for reorganization of it’s as Mantodea, Sanghar, bio-control agent. Empusidae, Liturgusidae, Mantidae, Tarachodidae . 1. INTRODUCTION ery rare papers published on praying mantids of 2. MATERIAL AND METHODS V(Sindh) Pakistan. -

(Dictyoptera: Mantodea) Fauna of Aspat (Strobilos), Bodrum, Mugla, Western Turkey

Research Article Bartın University International Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences JONAS, 3(2): 103-107 e-ISSN: 2667-5048 31 Aralık/December, 2020 A CONTRIBUTION TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE EMPUSIDAE, TARACHODIDAE AND MANTIDAE (DICTYOPTERA: MANTODEA) FAUNA OF ASPAT (STROBILOS), BODRUM, MUGLA, WESTERN TURKEY Nilay Gülperçin1*, Abbas Mol2, Serdar Tezcan3 1Natural History Application and Research Center, Ege University, Bornova, Izmir, Turkey 2 Health Academy, Deparment of Emergency Aid and Disaster Management, Aksaray University, Aksaray, Turkey 3Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Ege University, Bornova Izmir, Turkey Abstract This paper maintains data about the Mantodea (Dictyoptera) fauna from Aspat (Strobilos) province of Bodrum, Muğla, Western Turkey. Species were collected using different methods namely, handpicking on vegetation, handpicking on the ground, handpicking under stone, light trap, bait trap and sweep net sampling. Sampling took place at two weeks’ intervals during the years of 2008 and 2009. At the end of this research, three species belonging to three families of Mantodea were specified. Those are Empusa fasciata Brullé, 1832 (Empusidae), Iris oratoria (Linnaeus, 1758) (Tarachodidae) and Mantis religiosa (Linnaeus, 1758) (Mantidae). Sweeping net is the effective method (40.48%)in sampling and light trap (35.71%) method followed it. All three species were sampled in both years. E. fasciata was sampled in March-May, while I. oratoria was sampled in March-December and M, religiosa was sampled in June-November. Among those species Iris oratoria was the most abundant one. All these species have been recorded for the first time from Muğla province of Turkey. Keywords: Empusidae, Tarachodidae, Mantidae, Mantodea, Dictyoptera, fauna, Turkey 1. -

App-F3-Ecology.Pdf

June 2016 ZITHOLELE CONSULTING (PTY) LTD Terrestrial Ecosystems Assessment for the proposed Kendal 30 Year Ash Dump Project for Eskom Holdings (Revision 1) Submitted to: Zitholele Consulting Pty (Ltd) Report Number: 13615277-12416-2 (Rev1) Distribution: REPORT 1 x electronic copy Zitholele Consulting (Pty) Ltd 1 x electronic copy e-Library 1 x electronic copy project folder TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS ASSESSMENT - ESKOM HOLDINGS Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Site Location ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PART A OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 2 3.0 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 2 4.0 ECOLOGICAL BASELINE CONDITIONS ............................................................................................................ 2 4.1 General Biophysical Environment ............................................................................................................ 2 4.1.1 Grassland biome................................................................................................................................ 3 4.1.2 Eastern Highveld -

52 1 Entomologie 14-Xi-1980 Catalogue Des

Bull. Inst. r. Sei. nat. Belg. Bruxelles Bull. K. Belg. Inst. Nat. Wet. Brussel 14-XI-1980 1 52 1 ENTOMOLOGIE CATALOGUE DES ORTHOPTEROIDES CONSERVES DANS LES COLLECTIONS ENTOMOLOGIQUES DE L'INSTITUT ROYAL DES SCIENCES NATURELLES DE BELGIQUE BLATTOPTEROIDEA : 12me partie: Mantodea PAR P. VANSCHUYTBROECK (Bruxelles) Poursuivant l'inventaire du matériel Orthoptéroïdes des collections de l'Institut, nous publions, ci-dessous, le catalogue de la super-famille des Blattopteroïdea : Mantodea et la liste des exemplaires de valeur typique. La présente mise en ordre, la reche.vohe et l'authentification des types ont été réalisées par l'examen de tous les spécimens des diverses collections et les descr.iptions oüginales et ultérieures (SAUSSURE, STAL, de BORRE, GIGLIO-TOS, WERNER, BEIER, GÜNTHER et ROY). Nous avons suivi dans l'établissement du présent catalogue, la classification « Klassen und Ordnungen des Terreichs » par le Prof. Dr. M. BEIER. La collection de Mantides est fort importante et .comprend les familles suivantes : Chaeteessidae HANDLIRSCH; Metallyticidae CHOPARD; Amorphoscelidae STAL; Eremiaphilidae WOOD-MASON; Hymenopo didae CHOPARD; Mantidae BURMEISTER; Empusidae BURMEISTER, comportant 135 genres et 27 4 espèces. 2 P. VANSCHUYTBROECK 52, 29 I. - Famille des CHAETEESSIDAE HANDLIRSCH, 1926 1. - Genre Chaeteessa BURMEISTER, 1833. Chaetteessa BURMEISTER, 1833, Handb. Entom., 2, p. 527 (Hoplophora PERTY). T y p e d u g en r e . - Chaeteessa filata BURMEISTER. 1) Chaeteessa tenuis (PERTY), 1833, Delect. An. artic., 25, p. 127 (Hoplophora). 1 exemplaire : ô; Brésil (det. : SAUSSURE). II. - Famille des METALLYTICIDAE CHOPARD, 1946 2. - Genre Metallycus WESTWOOD, 1835. Metallycus WESTWOOD, 1835, Zool. Journ., 5, p. 441 (Metal leutica BURMEISTER). Type du genre . -

A Comparative Study of Structural Adaptations of Mouthparts in Mantodea from Sindh

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 41(1), pp. 21-27, 2009. A Comparative Study of Structural Adaptations of Mouthparts in Mantodea From Sindh Jawaid A. Khokhar* and N. M. Soomro Department of Zoology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro-76080 Pakistan Abstract.- Structural adaptations of mouthparts in seven species of the praying mantids belonging to families Empusidae, Eremiaphilidae, and Mantidae are reported. Key words: Mantodea, mouthparts, praying mantids, Sindh. INTRODUCTION 0030-9923/2009/0001-0021 $ 8.00/0 Copyright 2009 Zoological Society of Pakistan. Nawab shah, Larkana, Maini forest, Tando jam, Hala, Rani Bagh, Latifabad, Oderolal Station, The relationship between mouthparts Jamshoro, Kotri, Thatta by traditional insect hand structure and diet has been known for years. This net, hand picking and by using light trap on the bark connection between mouthparts morphology and of trees, shrubs, bushes and on grasses. specific food types is incredibly pronounced in class The observations were carried out on live insecta (Snodgrass, 1935). As insects have evolved praying mantids in open fields early in the morning. and adapted new food sources, their mouthparts After locating the species and quietly watching their have changed accordingly. This is extremely feeding for about 2 to 3 hours they were caught and important trait for evolutionary biologists (Brues, preserved for mouthparts study. For the study of 1929) as well as systematists (Mulkern, 1967). mouthparts, 5 specimens of each sex of each species Mantids are very efficient and deadly predators that were studied. The mouthparts were carefully capture and eat a variety of insects and other small extracted, boiled in 20%KOH, washed with distilled prey. -

Biodiversity Plan V1.0 Free State Province Technical Report (FSDETEA/BPFS/2016 1.0)

Biodiversity Plan v1.0 Free State Province Technical Report (FSDETEA/BPFS/2016_1.0) DRAFT 1 JUNE 2016 Map: Collins, N.B. 2015. Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: CBA map. Report Title: Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: Technical Report v1.0 Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Internal Report. Date: $20 June 2016 ______________________________ Version: 1.0 Authors & contact details: Nacelle Collins Free State Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs [email protected] 051 4004775 082 4499012 Physical address: 34 Bojonala Buidling Markgraaf street Bloemfontein 9300 Postal address: Private Bag X20801 Bloemfontein 9300 Citation: Report: Collins, N.B. 2016. Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: Technical Report v1.0. Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Internal Report. 1. Summary $what is a biodiversity plan This report contains the technical information that details the rationale and methods followed to produce the first terrestrial biodiversity plan for the Free State Province. Because of low confidence in the aquatic data that were available at the time of developing the plan, the aquatic component is not included herein and will be released as a separate report. The biodiversity plan was developed with cognisance of the requirements for the determination of bioregions and the preparation and publication of bioregional plans (DEAT, 2009). To this extent the two main products of this process are: • A map indicating the different terrestrial categories (Protected, Critical Biodiversity Areas, Ecological Support Areas, Other and Degraded) • Land-use guidelines for the above mentioned categories This plan represents the first attempt at collating all terrestrial biodiversity and ecological data into a single system from which it can be interrogated and assessed. -

Biodiversity and Biogeography of Praying Mantids in Sindh NM S

Sindh Univ. Res. Jour. (Sci. Ser.) Vol. 45 (2) 297-300 (2013) (2013) SI NDH UNIVERSITY RESEARCH JOURNAL (SCIENCE SERIES) Biodiversity and Biogeography of Praying Mantids in Sindh N. M. SOOMRO, J. A. KHOKHAR++, M.H. SOOMRO Department of Zoology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro- 76080 Pakistan Received 3th April 2012 and Revised 10th April 2012 Abstract: The study was undertaken to see the biodiversity and biogeography of Praying Mantids (Mantodea) belonging to families, Eremiaphilidae, Empusidae and Mantidae. Praying mantids were collected from 20 districts of Sindh Province during year 2010 and 2011. Total 380 specimens and 13 species including 2 new records were recorded. Species richness, Biodiversity Index and Index of diversity was determined. Keywords: Biodiversity, Biogeography, Mantodea, Praying Mantids, Sindh. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS Biodiversity refers to all the forms of Total numbers of 380 specimens were biological entities inhabitating the Earth-including collected and processed by standard entomological prokaryotes, wild plants and animals, micro- methods. Specimens stored in standard entomological organisms, domesticated animals and cultivated boxes with labels showing locality, date of collection plants, and even genetic material like seeds and and collector's name. Naphthalene balls were placed in germplasm Kothari (1992). Study on biodiversity of boxes to prevent the attack of ants and other insects. insects is of great importance because more than half Identification of specimens done with the help of keys of the world's known animal species are insects and descriptions given by Soomro et al. (2002) and by Wilson (1992). Biogeography is the study of patterns Ehrman's (2002) compressive catalogue of the mantids in the distribution of life and the processes that underlie of the world. -

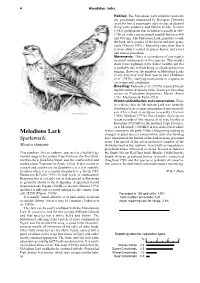

Melodious Lark Inhabits Relatively Dry Grasslands Dominated by Rooigras Themeda Triandra but It Sometimes Also Occurs in Planted Eragrostis Pastures and Fallow Fields

4 Alaudidae: larks Habitat: The Melodious Lark inhabits relatively dry grasslands dominated by Rooigras Themeda triandra but it sometimes also occurs in planted Eragrostis pastures and fallow fields. Vernon (1983c) pointed out that its habitat is usually at 550– 1750 m, with a mean annual rainfall between 400 and 800 mm. The Melodious Lark generally avoids the hard, wiry grasses of the alpine and sour grass- lands (Vernon 1983c). Reporting rates show that it is most often recorded in grassy Karoo, and sweet and mixed grasslands. Movements: There is no evidence of any regular seasonal movements in this species. The models show fewer sightings in the winter months, but this is probably due to birds being overlooked when not singing. However, the numbers of Melodious Larks in any area may vary from year to year (Tarboton et al. 1987b), implying movements in response to environmental conditions. Breeding: Tarboton et al. (1987b) reported breed- ing November–February in the Transvaal. Breeding occurs in Zimbabwe September–March (Irwin 1981; Masterson & Parks 1993). Historical distribution and conservation: There is evidence that the Melodious Lark was formerly distributed over a larger geographical area in south- ern Africa than it occupies presently (Vernon 1983c; Maclean 1993b). For example, there are no recent records of this species at its type locality at Kuruman (2723AD) in the northern Cape Province, or at Matatiele (3028BD) in KwaZulu-Natal where it was common in the early 1900s. Overgrazing leading to Melodious Lark changes in plant species composition, and crop farming Spotlewerik have transformed the habitat of this lark in many grassland areas. -

Acacia Flat Mite (Brevipalpus Acadiae Ryke & Meyer, Tenuipalpidae, Acarina): Doringboomplatmyt

Creepie-crawlies and such comprising: Common Names of Insects 1963, indicated as CNI Butterfly List 1959, indicated as BL Some names the sources of which are unknown, and indicated as such Gewone Insekname SKOENLAPPERLYS INSLUITENDE BOSLUISE, MYTE, SAAMGESTEL DEUR DIE AALWURMS EN SPINNEKOPPE LANDBOUTAALKOMITEE Saamgestel deur die MET MEDEWERKING VAN NAVORSINGSINSTITUUT VIR DIE PLANTBESKERMING TAALDIENSBURO Departement van Landbou-tegniese Dienste VAN DIE met medewerking van die DEPARTEMENT VAN ONDERWYS, KUNS EN LANDBOUTAALKOMITEE WETENSKAP van die Taaldiensburo 1959 1963 BUTTERFLY LIST Common Names of Insects COMPILED BY THE INCLUDING TICKS, MITES, EELWORMS AGRICULTURAL TERMINOLOGY AND SPIDERS COMMITTEE Compiled by the IN COLLABORATION WiTH PLANT PROTECTION RESEARCH THE INSTITUTE LANGUAGE SERVICES BUREAU Department of Agricultural Technical Services OF THE in collaboration with the DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, ARTS AND AGRICULTURAL TERMINOLOGY SCIENCE COMMITTEE DIE STAATSDRUKKER + PRETORIA + THE of the Language Service Bureau GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1963 1959 Rekenaarmatig en leksikografies herverwerk deur PJ Taljaard e-mail enquiries: [email protected] EXPLANATORY NOTES 1 The list was alphabetised electronically. 2 On the target-language side, ie to the right of the :, synonyms are separated by a comma, e.g.: fission: klowing, splyting The sequence of the translated terms does NOT indicate any preference. Preferred terms are underlined. 3 Where catchwords of similar form are used as different parts of speech and confusion may therefore -

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps DRAFT May 2009 South African National Biodiversity Institute Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Contents List of tables .............................................................................................................................. vii List of figures............................................................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2 Criteria for identifying threatened ecosystems............................................................... 10 3 Summary of listed ecosystems ........................................................................................ 12 4 Descriptions and individual maps of threatened ecosystems ...................................... 14 4.1 Explanation of descriptions ........................................................................................................ 14 4.2 Listed threatened ecosystems ................................................................................................... 16 4.2.1 Critically Endangered (CR) ................................................................................................................ 16 1. Atlantis Sand Fynbos (FFd 4) .......................................................................................................................... 16 2. Blesbokspruit Highveld Grassland