Is Podcasting Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Oliver Release 2015

AUSTRALIAN TOUR 2015 “The most intelligent political stand up you’ll see this year” The Times MELBOURNE PALAIS THEATRE THURSDAY 27 AUGUST Book at Ticketmaster 136 100 www.ticketmaster.com.au FRIDAY 28 AUGUST SYDNEY STATE THEATRE SUNDAY 30 AUGUST Book at Ticketmaster 136 100 www.ticketmaster.com.au MONDAY 31 AUGUST TICKETS ON SALE MONDAY 11 MAY 9AM One of Time MagAzine’s 100 Most InfluentiAl People, John Oliver, is an Emmy and Writer’s Guild AwArd winning writer. His HBO show, LAst Week Tonight with John Oliver, which won a Peabody Award in April this year, presents a satirical look at the week in news, politics and current events and is enjoying a second series. On his occasional breaks from television, John returns to his first love of stand-up and plays to sold out venues across the US. And now for the first time he comes to Australia for a stand up tour. “Wildly funny” The Telegraph From 2006 to 2013 John was a correspondent and guest host on the multi-award winning The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He first came to prominence as a cutting-edge political stand up in the UK, with a string of television appearances and sold-out solo shows at the Edinburgh FestivAl. With long-time collaborator Andy ZaltzmAn, John co-writes and co-presents the hugely popular weekly satirical podcast The Bugle. Its success has grown significantly since its inception in 2007 and now pulls in over 500,000 downloads a week. “A wonderfully intelligent comic” Evening Standard Having made the move to America in 2006 to work on The Daily Show, John won the BreAkout AwArd at the Aspen Comedy FestivAl in 2007 and went on to write and star in his first hour long Comedy Central stand up special John Oliver: Terrifying Times in 2008 which was then released on DVD. -

INDICATORS of JOURNALISTIC ROLE PERFORMANCE on LAST WEEK TONIGHT a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at T

INDICATORS OF JOURNALISTIC ROLE PERFORMANCE ON LAST WEEK TONIGHT A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Arthur A. Cook Bremer Dr. Brett Johnson, Thesis Committee Chair MAY 2019 © Copyright by Arthur A. Cook Bremer 2019 All Rights Reserve The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled INDICATORS OF JOURNALISTIC ROLE PERFORMANCE ON LAST WEEK TONIGHT presented by Arthur A. Cook Bremer, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Brett Johnson Dr. Victoria Johnson Dr. Ryan Thomas Dr. Tim Vos ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the guidance of Dr. Tim Vos for recommending a theoretical framework to help me explore this concept for my research. I would also like to thank Dr. Brett Johnson for his endless support and guidance throughout this entire process. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES AND GRAPHICS .............................................................................. iv Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 2. LITERATURE REVIEW .........................................................................................3 3. METHODS .............................................................................................................19 -

STG Presents an Average of 600 Events Annually at the Paramount, the Moore, and the Neptune Theatres As Well As at Other Venues Throughout the Region

STG presents an average of 600 events annually at The Paramount, The Moore, and The Neptune Theatres as well as at other venues throughout the region. Broadway productions, concerts, comedy, lectures, education & community programs, film, and other enrichment programs can be found in our venues. Please see below for a chronological list of performances. ● THING - CANCELLED - - Fort Worden ● AIN'T TOO PROUD - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Black Pumas - POSTPONED - - The Paramount Theatre ● John Hiatt & The Jerry Douglas Band - POSTPONED - - The Moore Theatre ● DANCE This! Virtual Performance - August 13, 2021 - Online ● Pop-Up Mini Golf at the Paramount Theatre - August 12 - 15 - The Paramount Theatre ● Tiny Meat Gang - CANCELLED - - The Moore Theatre ● Tune-Yards - August 7, 2021 - The Neptune Theatre ● Palaye Royale - POSTPONED - - The Neptune Theatre ● Joe Russo's Almost Dead - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● The Decemberists - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Up Next: Summer 2021 Series - July 24 - August 28, 2021 - Starbucks SODO Reserve ● The Masked Singer Live - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Jason Isbell and The 400 Unit - POSTPONED - - The Paramount Theatre ● IRC Residency - July 12, 2021 - Cascade View Elementary ● Girls Gotta Eat - POSTPONED - - The Moore Theatre ● More Music Songwriters Sessions 2021 - July 7, 2021 - Online ● STG Virtual AileyCamp 2021 - July 7 - August 4, 2021 - Online ● Pop-Up Donor Center with Bloodworks Northwest at The Paramount - July 6 - 9, 2021 - The Paramount Theatre ● Brit -

Inner Contradictions and Hidden Passages: Pedagogical Tact and the High-Quality Veteran Urban Teacher En Vue De Currere

INNER CONTRADICTIONS AND HIDDEN PASSAGES: PEDAGOGICAL TACT AND THE HIGH-QUALITY VETERAN URBAN TEACHER EN VUE DE CURRERE A dissertation submitted to the College and Graduate School of Education, Health, and Human Services Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rebecca Ann Zurava May 2006 © Copyright by Rebecca Ann Zurava 2006 All Rights Reserved ii A dissertation written by Rebecca Ann Zurava B.S.Ed, The Ohio State University, 1972 M.Ed., Kent State University, 1983 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2006 Approved by ______________________________ , Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee James G. Henderson ______________________________ , Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Eunsook Hyun ______________________________ , Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine Eggleston Hackney Accepted by ______________________________ , Chairperson, Department of Teaching, Kenneth Teitelbaum Leadership, and Curriculum Studies ______________________________ , Dean, College and Graduate School of Education, David A. England Health, and Human Services iii ACKN0WLEDGMENTS To my husband, George, whose life, labor, and love made this doctoral degree possible. George is the Emeritus Director of Resource Analysis and Planning at Kent State University. To James Henderson whose scholarly life led me to Pinar, Grumet, and pedagogical tact. To Eunsook Hyun who enthusiastically stepped forward to guide a stranger at her door. To Catherine Hackney who always believed in me. To these professors -

Podcasting: Considering the Evolution of the Medium and Its Association with the Word ‘Radio’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sunderland University Institutional Repository Berry, Richard (2016) Podcasting: Considering the evolution of the medium and its association with the word ‘radio’. The Radio Journal International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media, 14 (1). pp. 7-22. ISSN 14764504 Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/6523/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Podcasting: Considering the evolution of the medium and its association with the word ‘radio’ Richard Berry, University of Sunderland Publication details: The Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media. Volume 14, Issue 1. Pages 7-22 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/rjao.14.1.7_1 http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals/view-Article,id=21771/ Abstract When evaluating any new medium or technology we often turn to the familiar as a point of reference. Podcasting was no different, drawing obvious comparisons with radio. While there are traits within all podcasts that are radiogenic, one must also consider whether such distinctions are beneficial to the medium. Indeed, one might argue that when one considers the manner in which podcasts are created and consumed then there is an increasing sense in which podcasting can present itself as a distinct medium. While it is true to suggest that as an adaptable medium radio has simply evolved and podcasting is its latest iteration. In doing so, we might fail to appreciate the unique values that exist. -

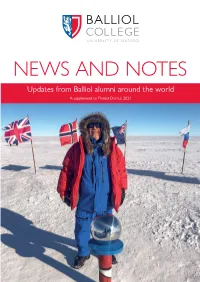

News and Notes 2021

NEWS AND NOTES Updates from Balliol alumni around the world A supplement to Floreat Domus 2021 Stuart Bebb NEWS AND NOTES NEWS AND NOTES News and Notes We are delighted to share news from the Balliol community Thomas Huxley (1949) provided limited scope for activities of 1940s No news. Just keeping my head down note. In fact, the most significant event in our wee Perthshire village and impacting my life was the closure of Edward Gelles considering myself to be exceedingly our indoor ice arenas, which resulted (1944) lucky still to be walking the dog, have in the likely end of my 80-year ice My study of an amazingly kind wife and be able to hockey career with both ‘a bang and European Jewry keep on with various projects. We have a whimper’. This had been the one began 20 years our Covid jabs tomorrow. Best wishes consistent chapter in my life story ago with a search to Balliol and all who sail in that ship. – through membership on school for my family teams, in competitive organisations, antecedents. It at the University of Toronto for four has developed years, with the OUIHC for three years into the much wider tracing of Jewish 1950s (including the legendary 29–0 win migrations in the context of our over Cambridge in 1955), and with continent’s history. I embarked on Roger Corman (1950) Oldtimer teams over the past 65 years, this interdisciplinary study of history, On 14 November 2009 Roger Corman culminating in my induction into the genealogy, genetics, and onomastics, was given an Oscar by the Academy Canadian Oldtimer Hockey Hall of drawing on birth, marriage, death, and of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Fame. -

Andy Zaltzman Rounds up the Year at Soho Theatre, Before Embarking on Nationwide Tour in 2017 with Brand New Show ‘Plan Z’

ANDY ZALTZMAN ROUNDS UP THE YEAR AT SOHO THEATRE, BEFORE EMBARKING ON NATIONWIDE TOUR IN 2017 WITH BRAND NEW SHOW ‘PLAN Z’ “The best political comedian in the business...Zaltzman is breathtakingly good” Time Out “Political comedy at its best” The Sunday Times Critically-acclaimed stand-up and star of the global hit satirical podcast The Bugle, ANDY ZALTZMAN will embark on his latest nationwide tour from February, following a run in London beginning on 20th December. ANDY will perform at Soho Theatre over Christmas and New Year with 2016: The Certifiable History, a satirical round-up of a year which has seen the world – Britain and non-Britain alike – bark furiously at its own reflection, punch itself angrily in the face, and take several long, hard, tearful baths with itself. From 2nd February he will head out on a 22-date tour with Plan Z, which will see ANDY address diverse issues such as the past, the present, and the future, attempting to body-surf the unending volcano of confused fury that is modern global politics. From its inception in 2007 until earlier this year, ANDY wrote and presented The Bugle with his long-term collaborator JOHN OLIVER (host of HBO’s Last Week Tonight). The podcast relaunched in October as part of the Radiotopia network, with ANDY joined by a revolving group of regular co-hosts including HARI KONDABOLU, NISH KUMAR, WYATT CENAC and HELEN ZALTZMAN. During its nine-year run The Bugle has covered all of the major news stories in the world, many of the minor news stories in the world, and a large amount of stuff that has not actually happened, becoming one of iTunes’ most popular and critically-acclaimed comedy podcasts. -

Comedy As an Instrument for Change: a Look at U.S. Political Television Satire During the Trump Presidency - and

Comedy as an instrument for change: A look at U.S. political television satire during the Trump presidency - and - Fake news: A look at deception and facts in the U.S. during the 21st century by Ellen Engelsbel B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2015 B.B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2015 Extended Essays Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Ellen Engelsbel 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITYSITY Fall 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Ellen Engelsbel Degree Master of Arts Titles Comedy as an instrument for change: A look at U.S. political television satire during the Trump presidency Fake news: A look at deception and facts in the U.S. during the 21st century Examining Committee: Chair: Dal Yong Jin Professor Martin Laba Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Date Defended/Approved: November 22, 2019 ii Abstracts Comedy as an instrument for change: A look at U.S. political television satire during the Trump presidency This essay examines television satire, why and how it is used in politics, as well as its efficacy in shedding light and awareness on serious topics. Also, it explores the potential of satire to motivate people to act and influence change. The essay includes examples of satirical television since the election of President Trump up to the release of the Mueller Report using content from John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight and Stephen Colbert’s Late Night with Stephen Colbert. -

Media, Journalism and Technology Predictions 2015 1

MEDIA, JOURNALISM AND TECHNOLOGY PREDICTIONS 2015 1 Nic Newman Digital Strategist: ([email protected], @nicnewman) This year, we’ve gone number crazy. There’s a look back at the 10 key trends of 2014, 10 significant predictions for mobile, 10 for journalism, 6 for the digital election + many more on social media, television, radio and advertising. Finally there are 7 emerging technologies and 10 start-ups to watch. But before all that, the key points: Wearables, hearables, nearables and payables will be some of the buzzwords of 2015 as the mobile revolution takes the next great leap. Mobile and social trends will continue to drive technical, product and content innovation with subscription and rental models increasingly driving digital revenues. In other news … • Smartphones cement their place as the single most important place for delivering digital journalism and become hubs for other devices • Messaging apps continue to drive the next phase of the social revolution • Visual personal media explodes fuelled by selfie sticks and selfie videos • Chinese and Indian companies begin to threaten Silicon Valley dominance of global tech • Television disruption hits its stride with over the top players (OTT) gaining ground • Move from page views/UVs towards attention and long term value • Media becomes more driven by context (location, history, preferences) less by platform • Ad blocking goes mainstream. Court cases ensue. Native advertising grows • We’re going to worry even more about our privacy and online security in 2015 • Rebirth of audio