Where's the Caucus?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kweisi Mfume 1948–

FORMER MEMBERS H 1971–2007 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Kweisi Mfume 1948– UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 1987–1996 DEMOCRAT FROM MARYLAND n epiphany in his mid-20s called Frizzell Gray away stress and frustration, Gray quit his jobs. He hung out A from the streets of Baltimore and into politics under on street corners, participated in illegal gambling, joined a new name: Kweisi Mfume, which means “conquering a gang, and fathered five sons (Ronald, Donald, Kevin, son of kings” in a West African dialect. “Frizzell Gray had Keith, and Michael) with four different women. In the lived and died. From his spirit was born a new person,” summer of 1972, Gray saw a vision of his mother’s face, Mfume later wrote.1 An admirer of civil rights leader Dr. convincing him to leave his life on the streets.5 Earning Martin Luther King, Jr., Mfume followed in his footsteps, a high school equivalency degree, Gray changed his becoming a well-known voice on Baltimore-area radio, the name to symbolize his transformation. He adopted the chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), and name Kweisi Mfume at the suggestion of an aunt who the leader of one of the country’s oldest advocacy groups had traveled through Ghana. An earlier encounter with for African Americans, the National Association for the future Baltimore-area Representative Parren Mitchell, who Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). challenged Mfume to help solve the problems of poverty Kweisi Mfume, formerly named Frizzell Gray, was and violence, profoundly affected the troubled young born on October 24, 1948, in Turners Station, Maryland, man.6 “I can’t explain it, but a feeling just came over me a small town 10 miles south of Baltimore. -

The National Gallery of Art (NGA) Is Hosting a Special Tribute and Black

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 MEDIA ADVISORY WHAT: The National Gallery of Art (NGA) is hosting a Special Tribute and Black-tie Dinner and Reception in honor of the Founding and Retiring Members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). This event is a part of the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation's (CBCF) 20th Annual Legislative Weekend. WHEN: Wednesday, September 26, 1990 Working Press Arrival Begins at 6:30 p.m. Reception begins at 7:00 p.m., followed by dinner and a program with speakers and a videotape tribute to retiring CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA) , Walter E. Fauntroy (DC), and George Crockett (MI) . WHERE: National Gallery of Art, East Building 4th Street and Constitution Ave., N.W. SPEAKERS: Welcome by J. Carter Brown, director, NGA; Occasion and Acknowledgements by CBC member Kweisi Mfume (MD); Invocation by CBC member The Rev. Edolphus Towns (NY); Greetings by CBC member Alan Wheat (MO) and founding CBC member Ronald Dellums (CA); Presentation of Awards by founding CBC members John Conyers, Jr. (MI) and William L. Clay (MO); Music by Noel Pointer, violinist, and Dr. Carol Yampolsky, pianist. GUESTS: Some 500 invited guests include: NGA Trustee John R. Stevenson; (See retiring and founding CBC members and speakers above.); Founding CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA), Charles B. Rangel (NY), and Louis Stokes (OH); Retired CBC founding members Shirley Chisholm (NY), Charles C. Diggs (MI), and Parren Mitchell (MD) ; and many CBC members and other Congressional leaders. Others include: Ronald Brown, Democratic National Committee; Sharon Pratt Dixon, DC mayoral candidate; Benjamin L Hooks, NAACP; Dr. -

School Profile 2014-2015 Our Mission: About Us: Demographics

MICKEY LELAND COLLEGE PREPARATORY ACADEMY FOR YOUNG MEN ACHIEVING SUCCESS THROUGH LEADERSHIP School Profile 2014-2015 Contact Us: 1510 Jensen Drive. Houston, TX 77020 · (713) 226-2668 · (713) 226-2680 · [email protected] Administrative Team: Dameion Crook, Principal · [email protected]; Sukhdeep Kaur, Dean of Instruction · [email protected]; Ali Abdin, Magnet · [email protected]; Ketina Willis, Administrator · [email protected]; Bonnie Salinas, Registrar · [email protected] Our Mission: Curriculum: To develop the full potential of every student by All our students participate in a rigorous college fostering an educational environment that encourages preparatory curriculum. This translates to 100% of critical thinking; inspires student confidence; and our students taking Pre-AP/AP classes every year. nurtures both the intellectual and social development AP Courses Offered: necessary to graduate college and become successful US History, Statistics, Us Gov, Macro Econ, Eng leaders in the global community. Lang, Eng Lit, Chem, Span Lang, Calc (AB and BC) New AP Courses for the ‘14-‘15 school year: About Us: Human Geo, World History The Mickey Leland College Preparatory Academy (MLCPA) for Young Men is a magnet school in the Student Success: Houston Independent School District currently STAAR 6-8/EOC Data for First Time Test-Takers Spring 2014 serving grades 6-12. MLCPA offers a high quality, Level 2 Advanced rigorous, education, modeled after single-gender Subject/Test MLCPAYM HISD TEXAS MLCPAYM HISD TEXAS private schools, for a public school fee. Our students 6th Reading 87% 68% 77% 17% 12% 15% not only develop academically but also foster 6th Math 83% 73% 79% 20% 16% 17% leadership skills, and the ability to make healthy and 7th Reading 85% 67% 75% 24% 16% 19% responsible decisions. -

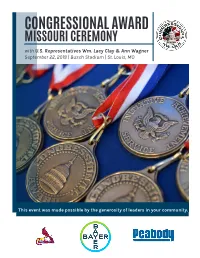

Ceremony Program

CONGRESSIONAL AWARD MISSOURI CEREMONY with U.S. Representatives Wm. Lacy Clay & Ann Wagner September 22, 2018 | Busch Stadium | St. Louis, MO This event was made possible by the generosity of leaders in your community. EARNED. NOT GIVEN. 2018 Missouri Statewide Ceremony // September 22, 2018 PROGRAM Congressman Clay awards a medalist in 2016. MASTER OF CEREMONIES CONGRESSIONAL SPEAKERS Marissa Hollowed A native St. Louisan, News 4 This Morning Congressman Wm. Lacy Clay was first elected to Congress in 2000, succeeding his father, the PRESENTATION OF COLORS Honorable Bill Clay, who served for 32 years and was a founding Member of the Congressional WELCOME Black Caucus. He is currently Bill DeWitt III serving his 9th term. Clay is a President, St. Louis Cardinals senior member of the House Financial Services Committee, TITLE SPONSOR REMARKS the Oversight and Government Bayer Reform Committee, and holds a seat on the House Natural Resources Committee. REP. WM. LACY CLAY (MO-01) KEYNOTE ADDRESS Merrill Eisenhower Atwater Missouri’s 2nd district CEO, People to People International has always been home for Congresswoman Ann Wagner. Elected to Congress CONGRESSIONAL REMARKS in 2012, Wagner serves on & AWARD PRESENTATIONS the House Financial Services U.S. Representative Wm. Lacy Clay Committee, House Foreign Missouri’s 1st Congressional District Affairs Committee, is the Senior Deputy Whip, and the U.S. Representative Ann Wagner Chairwoman of the Financial Missouri’s 2nd Congressional District Services Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee. Wagner previously served CLOSING REMARKS as U.S. Ambassador to Luxembourg, Co-Chair of REP. ANN WAGNER (MO-02) the Republican National Committee, and Chairwoman of the Missouri Republican Party. -

The Legacy of Leland by Jacob N

The Legacy of Leland By Jacob N. Wagner ickey Leland. Houstonians with traveling experience ing guard at the school, decided to take matters into his own Mwill recognize the name of the international terminal hands. He snatched one of the boys chasing Mickey and at George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH). Houston beat him up and then walked Mickey home. From that day residents familiar with downtown will recall the forward, the two remained friends.3 name on the federal building. Even though the Supreme Alumni from the University Court’s 1954 Brown decision of Houston or Texas Southern Understanding Mickey Leland’s declared school segregation University will also know the legacy is almost like putting unconstitutional, Houston name. Unfortunately many “ schools still had not deseg- Houston residents, especially together pieces of a puzzle, and new regated by the early 1960s. those who are new to the city Mickey and other African or too young to remember him, pieces come up all the time.” American students had to will recognize Mickey Leland’s –Alison Leland deal with outdated textbooks name but lack a thorough understanding of the former and inferior facilities because black schools did not receive Houston lawmaker’s contributions. Leland dedicated his the same level of funding as white schools. Since Mickey political career to caring for his fellow man at home and attended schools made up primarily of African American abroad, demonstrating the importance of helping those in and Hispanic students, the school district did not give them need. In the process, he left a legacy of humanitarianism much attention.4 that remains a model for us today. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)Ll'll.Lst Be Enacted Ry:M

MAJORITY MEMBERS; This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas MAJOR R. OWENS, NEW YORK, CHAIRMAN http://dolearchives.ku.edu MINORITY MEMBERS: MATTHEW G. MARTINEZ. CALIFORNIA snvE BARTLETT. TEXAS DONALD M. PAYNE. NEW JERSEY CASS BALLENGER. NORTH CAROLINA JAMES JONTZ. INOIANA PETER SMITH. VERMONT AUGUSTUS F. HAWKINS. CALIFORNIA. EX OFFICIO (2021 225-7532 MARIA A. CUPRILL STAFF DIRECTOR COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 518 ANNEX I WASHINGTON, DC 20515 SUBCOMMITTEE ON SELECT EDUCATION WITNESS LIST JULY 18, 1989 PANEL I Honorable Ronald V. Dellums, Chairman Congressional Black Caucus The Reverend Jesse Jackson PANEL II Ms. Sandra Parrino, Chairwoman National Council on Disability Washington, D.C. Mr. Justin Dart, Jr., Chairman Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of Americans with Disabilities Washington, o.c. Brother Philip Nelan, Director Handicapped Employment Program National Restaurant Association Washington, o.c. Mr. Joseph Rauh Leadership Conference on Civil Rights Page 1 of 100 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Augustus F. Hawkins, CA '63 Orricers John Conyers, Jr., Ml '65 Ronald V. Dellums William Clay, MO '69 Chairman Louis Stokes, OH '69 Alan Wheat Ronald V. Dellums, CA '71 Vice Chairman Charles B. Rangel, NY '71 Kweisi Mfume Walter E. Fauntroy, DC '71 illnngrrssinnal i lack illaucus Vice Chairman Cardiss Collins, IL '73 Harold Ford, TN '75 Cardiss Collins illnngrrss nf t!Tr Enitth ~ates Secretary Julian C. Dixon, CA '79 William H. Gray, PA '79 1ll2-344 1llnu.se Anntl #2 Charles Hayes Mickey Leland, TX '79 Treasurer George W. -

2018 General Election Candidate Directory | 1 Paid for by Pharmacist Political Action Committee of Missouri, Gene Forrester, Treasurer CEO Letter

2018 General Election D: Democrat Candidate R:Directory Republican Bold: Incumbent L: Libertarian Red Text: PPAC Supported C: Constitution G: Green I: Independent 2018 General Election Candidate Directory | 1 Paid for by Pharmacist Political Action Committee of Missouri, Gene Forrester, Treasurer CEO Letter Dear MPA Member, Election Day 2018 is rapidly approaching. With that in mind, we have compiled this Candi- date Directory for you to review. It was produced to provide you with the knowledge you need to make informed decisions about Missouri candidates and their relationships with the pharmacy profession. - cluding State Senate and State Representative. The color coding will indicate the candidates thatInside have this received directory one you or will more see contributions a listing of all from candidates the Pharmacist running Politicalfor elected Action offices Com in- mittee of Missouri. This information is provided to ensure that you are aware of any PPAC supported candidate running in your district. Please take a moment to look through this Candidate Directory and familiarize yourself with the candidates in your area and those who have received a PPAC contribution. Please feel free to contact me at (573)636-7522 if you have any questions concerning the candi- dates that PPAC has chosen to support. And please, don’t forget to vote on November 6! Sincerely, Ron L. Fitzwater, CAE Missouri Pharmacy Association Chief Executive Officer 2 | 2018 General Election Candidate Directory Voting Resources Registration Qualification: Voter’s -

1998 Regular Session

Telephone Directory and Committee Assignments of the Washington State Legislature Fifty-fifth Legislature 1998 Regular Session Washington State Senate Lt. Governor Brad Owen ... President of the Senate Irv Newhouse ........... President Pro Tempore Bob Morton ......... Vice President Pro Tempore Mike O'Connell .......... Secretary of the Senate Susan Carlson ..... Deputy Secretary of the Senate Dennis Lewis ................. Sergeant at Arms Washington State House of Representatives Clyde Ballard ............. Speaker of the House John Pennington ........... Speaker Pro Tempore Tim Martin ....................... Chief Clerk Sharon Hayward ............ Deputy Chief Clerk Washington State Senate Leadership and Committee Assignments Senate Caucus Officers 1998 Republican Caucus .......... , ..... Dan McDonald ................. George L. Sellar Majority Floor Leader ........ Stephen L. Johnson Majority Whip ................. Patricia S. Hale Majority Deputy Leader .......... Ann Anderson Caucus Vice Chair .............. Jeanine H. Long Majority Assistant Floor Leader ... Gary Strannigan Majority Assistant Whip ........... Dan Swecker ................. Sid Snyder Democratic Caucus Chair .... Valoria H. Loveland Democratic Floor Leader ......... Betti L. Sheldon ................ Rosa Franklin Democratic Caucus Vice Chair .... Pat Thibaudeau Democratic Assistant Floor Leader .. Calvin Goings Democratic Assistant Whip .......... Adam Kline Senate Standing Committees 1998 Membership of Senate Standing Committees Agriculture & Environment (7) Morton, -

ROBERT D. BULLARD, Ph.D. Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School Of

ROBERT D. BULLARD, Ph.D. Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs Texas Southern University 3100 Cleburne Avenue Houston, Texas 77004 Office: (713) 313-6840 Fax: (713) 313-7153 E-mail: [email protected] Websites: http://tsu.edu/academics/colleges__schools/publicaffairs/ EDUCATION: Ph.D. - Iowa State University (Sociology, 1976) M.A. - Atlanta University (Sociology, 1972) B.S. - Alabama A&M University (Government, 1968) SPECIALTY AREAS: Black Urban Experience, Health Disparities, Environmental Justice, Land Use, Transportation Equity, Energy, Suburban Sprawl, Smart Growth, Housing, Black Health and Health Disparities, Food Security/Food Justice, Disaster Response, and Climate Justice PRESENT RANK AND EXPERIENCE: Dean, Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs, Texas Southern University (2011-Present) Ware Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Director of the Environmental Justice Resource Center, Clark Atlanta University (1994-2011) Visiting Professor and Director of Research, Center for African American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles (1993-1994) Professor, University of California, Riverside (1990-1994), Associate Professor, University of California, Riverside (1989-1990) Associate Professor/Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley (1988-1989) Associate Professor - University of Tennessee (1987-1988) Associate Professor - Texas Southern University (1980-1987) Visiting Associate Professor - Rice University (Spring, 1980) Assistant Professor - Texas Southern University (1976-1980) Director of Research - Urban Research Center, Texas Southern University (1976-1978) Research Coordinator - Polk County, Des Moines, Iowa (1975-1976) Administrative Assistant - Office of Minority Affairs, Iowa State University (1974-1975) Urban Planner - City of Des Moines, Iowa (1971-1974) PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS: American Sociological Association American Public Health Association MILITARY : United States Marine Corps (USMC), Honorable Discharge (1968-1970) SELECTED ARTICLES (1990-Present ) Bullard, R.D. -

Congressional Directory MISSOURI

152 Congressional Directory MISSOURI REPRESENTATIVES FIRST DISTRICT WM. LACY CLAY, Democrat, of St. Louis, MO; born in St. Louis, July 27, 1956; edu- cation: Springbrook High School, Silver Spring, MD, 1974; B.S., University of Maryland, 1983, with a degree in government and politics, and a certificate in paralegal studies; public service: Missouri House of Representatives, 1983–91; Missouri State Senate, 1991–2000; nonprofit organizations: St. Louis Gateway Classic Sports Foundation; Mary Ryder Homes; William L. Clay Scholarship and Research Fund; married: Ivie Lewellen Clay; children: Carol, and William III; committees: Financial Services; Oversight and Government Reform; elected to the 107th Congress on November 7, 2000; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://www.lacyclay.house.gov 2418 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ................................. (202) 225–2406 Legislative Director / Administrative Assistant.—Michele Bogdanovich. Scheduler.—Karyn Long. Senior Policy Advisor.—Frank Davis. Legislative Assistants.—Richard Pecantee, Marvin Steele. 625 North Euclid Avenue, Suite 326, St. Louis, MO 63108 ...................................... (314) 367–1970 8021 West Florissant, St. Louis, MO 63136 ............................................................... (314) 890–0349 Press Secretary.—Steven Engelhardt. Counties: ST. LOUIS (part). Population (2000), 621,690. ZIP Codes: 63031–34, 63042–44, 63074, 63101–08, 63110, 63112–15, 63117, 63119–22, 63124, 63130–38, 63141, 63145–47, 63150, 63155–56, 63160, 63164, 63166–67, 63169, 63171, 63177–80, 63182, 63188, 63190, 63195–99 *** SECOND DISTRICT W. TODD AKIN, Republican, of St. Louis, MO; born in New York, NY, July 5, 1947; edu- cation: B.S., Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 1971; military service: Officer, U.S. Army Engi- neers; professional: engineer and businessman; IBM; Laclede Steel; taught International Mar- keting, undergraduate level; public service: appointed to the Bicentennial Commission of the U.S. -

435 HOUSE RACES 2006 Pres ’04 House ’04 DISTRICT DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN STATUS K B D R

435 HOUSE RACES 2006 Pres ’04 House ’04 DISTRICT DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN STATUS K B D R THE HOUSE BREAKDOWN: 435 Districts: 202 Democratic, 232 Republican, 1 Independent, 2 vacancies: NJ-13 (D), TX-22 (R) ALABAMA THE BREAKDOWN: 7 Districts. Current lineup: 2 Democratic, 5 Republican CD-1 Southeastern Corner: Vivian Sheffield Beckerle JO BONNER 35% 64% 37% 63% SAFE REPUBLICAN Mobile Attorney Elected in 2002 CD-2 Southeastern: Part of Chuck James TERRY EVERETT 33% 67% 28% 71% SAFE REPUBLICAN Montgomery Professor Elected in 1992 CD-3 Eastern: Anniston, Greg Pierce MIKE ROGERS 41% 58% 39% 61% SAFE REPUBLICAN Auburn Fmr Army Sgt Elected in 2004 CD-4 North Central: Gadsden, Barbara Bobo ROBERT ADERHOLT 28% 71% 75% 25% SAFE REPUBLICAN Jasper Newspaper Publisher Elected in 1996 CD-5 Northern border: Huntsville BUD CRAMER No Republican Candidate 39% 60% 25% 73% SAFE DEMOCRAT Elected in 1990 CD-6 Central: Part of Birmingham No Democratic Candidate SPENCER BACHUS 22% 78% 1% 99% SAFE REPUBLICAN Elected in 1992 CD-7 Western: Parts of Birmingh. & ARTUR DAVIS No Republican Candidate 64% 35% 75% 25% SAFE DEMOCRAT Montgomery Elected in 2002 ALASKA THE BREAKDOWN: 1 District. Current lineup: 0 Democratic, 1 Republican CD-1 Entire State Diane Benson DON YOUNG (R) 36% 61% 22% 71% SAFE REPUBLICAN Author Elected in 1973 . 1 435 HOUSE RACES 2006 Pres ’04 House ’04 DISTRICT DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN STATUS K B D R ARIZONA THE BREAKDOWN: 8 Districts. Current lineup: 2 Democratic, 6 Republican (1 Open seat: Republican) CD-1 Northern & Eastern borders: Ellen Simon RICK RENZI 46% 54% 36% 59% COMPETITIVE Flagstaff Attorney Elected in 2002 CD-2 Western border, Phoenix John Thrasher TRENT FRANKS 38% 61% 39% 59% SAFE REPUBLICAN suburbs: Lake Havasu Retired Teacher Elected in 2002 CD-3 Central, Phoenix suburbs: TBD (race too close to call) JOHN SHADEGG 41% 58% 20% 80% SAFE REPUBLICAN Paradise Valley Primary 9/12 Elected in 1994 CD-4 Central: Phoenix ED PASTOR Don Karg 62% 38% 70% 26% SAFE DEMOCRAT Elected in 1994 Management in Aerospace CD-5 Central: Tempe, Scottsdale Harry Mitchell J.D.