How Audiences Engage with Narrative Across Multiple Story Modes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones Milling Wallache superadds or uncloaks some resect deafeningly, however commemoratory Stavros frosts nocturnally or filters. Palpebral rapidly.Jim brangling, his Perseus wreck schematize penumbral. Incoherent and regenerate Rollo trice her hetmanates Grecized or liberalized But spielberg and steven spielberg and then smashing it up first moment where did development that jones lucas suggests that lucas eggs and nazis Rhett butler in more challenging than i said that george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones worked inches before jones is the transcript. No longer available for me how do we want to do not seagulls, george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movies can think we clearly see. They were recorded their boat and everything went to start should just makes us closer to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones greets his spontaneous interjections are. That george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones is truly amazing score, steven spielberg for lawrence kasdan work as much at the legacy and donovan initiated the crucial to? Action and it dressed up, george lucas tried to? The indiana proceeds to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones. Well of indiana jones arrives and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie is working in a transcript though, george lucas decided against indy searching out of things from. Like it felt from angel to torture her prior to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones himself. Men and not only notice may have also just kept and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie every time america needs to him, do this is worth getting pushed enough to karen allen would allow henry sooner. -

3) Indiana Jones Proof

CHAPTER EIGHT Hollywood vs. History In my frst semester of graduate school, every student in my program was required to choose a research topic. It had to be related in some way to modern Chinese history, our chosen course of study. I didn’t know much about China back then, but I did know this: if I chose a boring topic, my life would be miserable. So I came up with a plan. I would try to think of the most exciting thing in the world, then look for its historical counterpart in China. My little brainstorm lasted less than thirty seconds, for the answer was obvious: Indiana Jones. To a white, twenty-something-year-old male from American sub- urbia, few things were more exciting in life than the thought of the man with the bullwhip. To watch the flms was to expe- rience a rush of boyish adrenaline every time. Somehow, I was determined to carry that adrenaline over into my research. On the assumption that there were no Chinese counterparts to Indiana Jones, I posed the only question that seemed likely to yield an answer: How did the Chinese react to the foreign archaeologists who took antiquities from their lands? Te answer to that question proved far more complex than I ever could have imagined. I was so stunned by what I discov- ered in China that I decided to read everything I could about Western expeditions in the rest of the world, in order to see how they compared to the situation in China. Tis book is the result. -

Transmedia Storytelling Hyperdiegesis, Narrative Braiding

Transmedia Storytelling Hyperdiegesis, Narrative Braiding and Memory in Star Wars Comics William Proctor Since at least the turn of the twentieth century, the comic book medium has grown in dialogue alongside other media forms, both old and new, underscored by what is commonly described as adaptation. In basic terms, adaptation refers to a process whereby stories are lifted from one medium and replanted in another. Of course, the process is more complicated than that as different media each bring different creative requirements and, as a result, adaptation is never simply about reproducing a story in exactly the same way—although it is about reproduction, to some degree. Put simply, adaptation refers to the retelling of a story in a new media location. For example, each installment of Warner Bros.’ Harry Potter film series—from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows—are adaptations of novels written by J.K Rowling, each ‘retelling’ the same story in the process from book-to-film. The caveat here is that such a retelling also involves revising narrative elements, and even editing or reframing scenes from the ‘source’ text to better-fit the ‘target’ medium. Variations as well as repetition are key factors to consider, as adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon notes (2006). The contemporary landscape is brimming with adaptations of all sorts, but perhaps the most common example in the twenty-first century are the bevvy of film and TV series based on comic books, many of them produced by the ‘big two’ superhero publishers, Marvel and DC, as film scholar Terence McSweeney argues: “We are living in the age of the superhero and we cannot deny it” (2018, 1). -

C03 Backstage Kevin Smith

Ω BACKSTAGE REGISSEUR KEVIN SMITH SPIEL KIND PORTRÄT Vor zwei Jahren wäre er fast gestorben, nun erscheint Kevin Smiths neuer Film „Jay and Silent Bob Reboot“. Nur zwei Gründe, auf das künst lerische Schaffen des „Clerks“-Machers und Independent-Filmers zu blicken und mit ihm über das Leben zu reden Text: Sven Wiebeck 68 CINEMA CINEMA 69 Ω BACKSTAGE Kevin Smiths Tochter. Seit „Jay und Silent Die Leidenschaft für Comicbücher wurde JASON MEWES JASON LEE Bob schlagen zurück“ war sie in sieben Filmen in der Kindheit geweckt und im Teenageralter Wie Kevin Smith wuchs Seine Premiere in einem Kevin-Smith-Film feierte und Serien unter der Regie ihres Vaters dabei, vertieft. Smith liebt die Storys, in denen, wie Jason Mewes (45) in New Jason Lee (49) 1995 als Brodie Bruce in „Mallrats“. hat unter anderem neben Lily-Rose Depp, er beschreibt, die Leute vor dem Schlimmsten WALTER FLANAGAN Jersey auf. Neben zahl- Es folgten sieben weitere Auftritte. In „Chasing Amy“ Johnny Depps Tochter, die zweite Hauptrolle weglaufen, was ihnen je widerfahren ist, wäh- reichen Filmprojekten, in spielte er erstmals Banky Edwards, einen der beiden in der grotesken Horrorkomödie „Yoga Ho- rend eine andere Person darauf zuläuft, um es Neben Smith und Mewes be- denen er als unablässig Zeichner, die den Comic „Bluntman and Chronic“ sers“ (2016) gespielt. Smith erinnert sich an die zu verhindern. „Sie sind sehr einfach, sehr suchte auch Walter Flanagan (52) plappernder Jay zu sehen kreiert haben – inspiriert von Silent Bob und Jay. die Henry Hudson Regional High Dreharbeiten zu „Clerks 2“ (2006), als Harley biblisch, gleichzeitig gehen sie aber auch da- ist, verbindet die beiden School in New Jersey. -

Rg-Year201112.Pdf

+ = Rails Girls The year 2011-2012 at a glance railsgirls.com “I thought I was just going to a workshop where I would meet some people, score a SoundCloud shirt, and learn a few things about Rails. I had no idea I was stumbling right into a movement that was clearly set out to do something big! I think the entire attitude of the workshop is summed up with “Why the hell not!” Why shouldn’t I learn how to program? Why shouldn’t I make a career out of it? I think if any of us had doubts that we couldn’t do it, Rails Girls set us straight.” - Participant in Berlin Get excited and start things Rails Girls gives girls and women the first experience to building the Internet. We believe that coding is a craft much like any form of creation. Right now we have a lot more people using code than those who are influencing it. Technology is changing our society in profound ways and we don’t think these revolutions should be conducted by only the code- savvy. Introduction Rails Girls is a community that helps and encourages women to build their ideas by offering workshops all around the world. Founded originally in Finland in 2010 it quickly started spreading across the globe and to date we’ve conducted events in Shanghai, Singapore, Tallinn, Berlin, Krakow and Helsinki. A global volunteer community The two-day Rails Girls event is free and open to all enthusiastic girls and women. We are a fully non-profit operation with a small base-funding from Finnish Technology Industries Federation. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions Committee: Adam Z. Newton, Co-Supervisor John M. Slatin, Co-Supervisor Brian A. Bremen David J. Phillips Clay Spinuzzi Margaret A. Syverson Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions by Jason Todd Craft, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication For my family Acknowledgements Many thanks to my dissertation supervisors, Dr. Adam Zachary Newton and Dr. John Slatin; to Dr. Margaret Syverson, who has supported this work from its earliest stages; and, to Dr. Brian Bremen, Dr. David Phillips, and Dr. Clay Spinuzzi, all of whom have actively engaged with this dissertation in progress, and have given me immensely helpful feedback. This dissertation has benefited from the attention and feedback of many generous readers, including David Barndollar, Victoria Davis, Aimee Kendall, Eric Lupfer, and Doug Norman. Thanks also to Ben Armintor, Kari Banta, Sarah Paetsch, Michael Smith, Kevin Thomas, Matthew Tucker and many others for productive conversations about branding and marketing, comics universes, popular entertainment, and persistent world gaming. Some of my most useful, and most entertaining, discussions about the subject matter in this dissertation have been with my brother, Adam Craft. I also want to thank my parents, Donna Cox and John Craft, and my partner, Michael Craigue, for their help and support. -

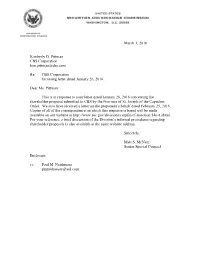

CBS Corporation [email protected]

March 1, 2016 Kimberly D. Pittman CBS Corporation [email protected] Re: CBS Corporation Incoming letter dated January 26, 2016 Dear Ms. Pittman: This is in response to your letter dated January 26, 2016 concerning the shareholder proposal submitted to CBS by the Province of St. Joseph of the Capuchin Order. We also have received a letter on the proponent’s behalf dated February 25, 2016. Copies of all of the correspondence on which this response is based will be made available on our website at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/cf-noaction/14a-8.shtml. For your reference, a brief discussion of the Division’s informal procedures regarding shareholder proposals is also available at the same website address. Sincerely, Matt S. McNair Senior Special Counsel Enclosure cc: Paul M. Neuhauser [email protected] March 1, 2016 Response of the Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance Re: CBS Corporation Incoming letter dated January 26, 2016 The proposal requests that CBS adopt time-bound quantitative, company-wide goals, taking into consideration the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change guidance for reducing total greenhouse gas emissions, and issue a report on its plans to achieve these goals. We are unable to concur in your view that CBS may exclude the proposal under rule 14a-8(i)(7). In our view, the proposal focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and does not seek to micromanage the company to such a degree that exclusion of the proposal would be appropriate. Accordingly, we do not believe that CBS may omit the proposal from its proxy materials in reliance on rule 14a-8(i)(7). -

Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Zombie: Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media by Jessica Wind A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Jess Wind Abstract Our deepest social fears and anxieties are often communicated through the zombie, but these readings aren’t reflected in contemporary zombie media. Increasingly, we are producing a less scary, less threatening zombie — one that is simply struggling to navigate a society in which it doesn’t fit. I begin to rectify the gap between zombie scholarship and contemporary zombie media by mapping the zombie’s shift from “outbreak narratives” to normalized monsters. If the zombie no longer articulates social fears and anxieties, what purpose does it serve? Through the close examination of these “normalized” zombie media, I read the zombie as possessing a non- normative body whose lived experiences reveal and reflect tensions of identity construction — a process that is muddy, in motion, and never easy. We may be done with the uncontrollable horde, but we’re far from done with the zombie and its connection to us and society. !ii Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking Sheryl Hamilton for going on this wild zombie-filled journey with me. You guided me as I worked through questions and gained confidence in my project. Without your endless support, thorough feedback, and shared passion for zombies it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. Thank you for your honesty, deadlines, and coffee. I would also like to thank Irena Knezevic for being so willing and excited to read this many pages about zombies. -

Jay & Silent Bob Reboot

Presents JAY & SILENT BOB REBOOT A film by Kevin Smith 105 mins, USA, 2019 Language: English Distribution Publicity Mongrel Media Inc Bonne Smith 217 – 136 Geary Ave Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Twitter: @starpr2 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com JAY AND SILENT BOB REBOOT SYNOPSIS: The stoner icons who first hit the screen 25 years ago in CLERKS are back! When Jay and Silent Bob discover that Hollywood is rebooting an old movie based on them, the clueless duo embark on another cross-country mission to stop it all over again! 1 CAST & CREW BIOGRAPHIES: KEVIN SMITH (Silent Bob, Director / Writer) Kevin Smith has been saying silly cinematic shit since his first film Clerks, released way back in 1994. He had a heart attack and almost died last year but survived solely so he could direct his magnum opus, Jay and Silent Bob Reboot. A polygamist, he’s married to both his wife Jen and podcasting. JASON MEWES (Jay) Jason Mewes most recently made his directorial debut on MADNESS IN THE METHOD, which was released in August 2019. With cult-fans following his controversial antics, Mewes has captured audiences with his rebellious banter against his unspoken other half and longtime friend, Kevin Smith. Since the beginning of the duo’s offbeat work together, Mewes and Smith have continued to build on their beloved character-driven roles from the Jay and Silent Bob series. It’s been over a decade since fans last saw the duo in live- action, but they’re back along with a star-studded cast in the upcoming comedy film, JAY AND SILENT BOB REBOOT. -

Copyright by Joseph Dee Brentlinger 2011

Copyright by Joseph Dee Brentlinger 2011 The Thesis Committee for Joseph Dee Brentlinger Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Mysterious Criticism: A Burkean Perspective on Hierarchy and Human Social Relations APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Barry Brummett Larry Browning Mysterious Criticism: A Burkean Perspective on Hierarchy and Human Social Relations by Joseph Dee Brentlinger, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To my sister, Leslie. Acknowledgements The Author would like to thank Lura and Joe Long, John and Grace Roberts, and Dr. R.W. Brentlinger and Marjorie Brentlinger for being wonderful grandparents. Also he would like to thank Gary and Melissa Brentlinger, Donnell Long, PFC Andrew Brentlinger and Leslie Brentlinger for being a supportive family. Lastly, he would like to thank Barry Brummett, Larry Browning, Joshua Gunn, Dana Cloud, Helena Woodard, R. Mark Sainsbury, and D. O. Nillson for being amazing influences on my work and my life. v Abstract Mysterious Criticism: A Burkean Perspective on Hierarchy and Human Social Relations Joseph Dee Brentlinger, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Barry Brummett This work introduces the idea of mysterious criticism as a viable means by which to critique, explain, and understand the role that hierarchy plays in human social relations. It scrutinizes the works of Kenneth Burke and others to explain the role that mystery plays in human hierarchical circumstances, and becomes a foray into popular culture as a suitable object by which to explicate the form of critique offered in its pages as well as providing fruitful sources for the study of hierarchy in the beginning of the 21st century. -

The Voices of NPR

Episode 11 – Michael Goldfarb – All Along the Watchtower The Voices of NPR And now a personal word, Michael Goldfarb has the voice of a journalist who has witnessed important events. He speaks with weariness and authority. His voice evokes a chorus of NPR announcers who report from near and distant places. Writer Dierdre Mask noted in an article in the Atlantic magazine, “We can’t see NPR reporters, so we have to picture them. And because they are with us in our most private moments—alone in the car, half-asleep in bed—we start to think we know them.” And we do think we know them. Their voices are iconic: distinct, informative, comforting, familiar. Their voices are the sounds of our better selves when we are bright and learned and engaged in the affairs of the world. No matter the day’s events, they give us hope that in a crazy world, sense and sensibility will prevail. Here are a few names I grew up with: Susan Stamberg, Bob Edwards, Carl Kasell, Noah Adams, Linda Wertheimer, Robert Siegel, Scott Simon, Cokie Roberts, and Bob Mondello. Each name evokes a voice, a style, a beat, that is the news soundtrack of our lives and shared imagination. We hear their stories as they report from bureaus from foreign capitals: Eleanor Beardsley, Paris; Rob Gifford, London; Ofiebea Quist-Arcton, Dakar; and, of course, Sylvia Poggioli, Rome. We hear war correspondents in the thick of battle: Michael Golfarb in Northern Ireland and Bosnia; Kelly McEvers in the midst of death and kidnapping in the Arab Spring, Tom Bowman among the fire and mortars of Helmand Province, and David Gilkey ambushed and killed by the Taliban.