Report of the Portfolio Committee on Labour on the Workshops and Public Hearings Held on the National Minimum Wage, Dated 8 March 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

Seven Priorities to Drive the National Development Plan – President Ramaphosa

Oath of office 7 6 reminds MPs 8 Smaller parties of their duty to all NA and NCOP promise tough South Africans, will put the oversight in says Chief Justice people first 6th Parliament Mogoeng Vol. 01 Official Newspaper of the Parliament of the Republic of South Africa Issue 03 2019 The Speaker of the NA, Ms Thandi Modise (left), President Cyril Ramaphosa, the first lady Tshepo Motsepe and the Chairperson of the NCOP, Mr Amos Masondo (far right) on the steps of the NA. Seven priorities to drive the National Development Plan – President Ramaphosa President Cyril social cohesion and safe of the national effort, to make communities, a capable, ethical it alive, to make it part of the Ramaphosa told and developmental state, a lived experience of the South the nation that his better Africa and world. African people. government will focus on seven priorities, He said all the government “As South Africa enters the programmes and policies next 25 years of democracy, writes Zizipho Klaas. across all departments and and in pursuit of the objectives agencies will be directed in of the NDP, let us proclaim a The priorities are, economic pursuit of these overarching bold and ambitious goal, a transformation and job tasks. unifying purpose, to which we creation, education, skills and dedicate all our resources and health, consolidating the social At the same time, President energies,” he stressed. wage through reliable and Ramaphosa said the quality basic services, spatial government must restore the Within the priorities of this integration, human settlements National Development Plan administration, President and local government, (NDP) to its place at the centre Ramaphosa said 2 The Khoisan praise singer praises President Ramaphosa. -

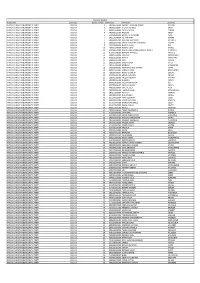

Party List Rank Name Surname African Christian Democratic Party

Party List Rank Name Surname African Christian Democratic Party National 1 Kenneth Raselabe Joseph Meshoe African Christian Democratic Party National 2 Steven Nicholas Swart African Christian Democratic Party National 3 Wayne Maxim Thring African Christian Democratic Party Regional: Western Cape 1 Marie Elizabeth Sukers African Independent Congress National 1 Mandlenkosi Phillip Galo African Independent Congress National 2 Lulama Maxwell Ntshayisa African National Congress National 1 Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa African National Congress National 2 David Dabede Mabuza African National Congress National 3 Samson Gwede Mantashe African National Congress National 4 Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma African National Congress National 5 Ronald Ozzy Lamola African National Congress National 6 Fikile April Mbalula African National Congress National 7 Lindiwe Nonceba Sisulu African National Congress National 8 Zwelini Lawrence Mkhize African National Congress National 9 Bhekokwakhe Hamilton Cele African National Congress National 10 Nomvula Paula Mokonyane African National Congress National 11 Grace Naledi Mandisa Pandor African National Congress National 12 Angela Thokozile Didiza African National Congress National 13 Edward Senzo Mchunu African National Congress National 14 Bathabile Olive Dlamini African National Congress National 15 Bonginkosi Emmanuel Nzimande African National Congress National 16 Emmanuel Nkosinathi Mthethwa African National Congress National 17 Matsie Angelina Motshekga African National Congress National 18 Lindiwe Daphne Zulu -

Annual Report 2010/11

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 / 2011 eThekwini Municipality Contact Details P.O. Box 1014 Email: [email protected] Durban Website: www.durban.gov.za 4000 CONTENTS Page No. Volume One Preface 3 Acronyms 4 Chapter One Mayor's Foreword 8 Municipal Manager's Overview 10 Chapter Two Governance 12 2.1 Introduction to governance 12 2.2 Political governance 12 2.3 Administrative governance 16 2.4 International and Intergovernmental relations 17 Chapter Three Service Delivery Performance 19 3.1 Introduction 19 3.2 Water Provision 20 3.3 Waste Water (Sanitation) Provision 23 3.4 Electricity Provision 27 3.5 Waste Management 30 3.6 Housing 32 3.7 Roads 33 3.8 Transport 35 3.9 Stormwater Drainage 37 3.10 Local Economic Development ( including Tourism and Markets) 39 3.11 Security and Safety 43 3.12 Disaster Management 44 3.13 Fire and Emergency Services 45 3.14 Performance Monitoring and Evaluation 47 Chapter Four Organisational Development Performance 106 4.1 Introduction 106 4.2 Employees 106 4.3 Managing the Municipal Workforce 109 4.4 Capacitating the Municipal Workforce 111 4.5 Managing the Workforce Expenditure 111 Chapter Five Financial Performance 113 5.1 Introduction 113 5.2 Statements of Financial Performance 113 5.3 Grants 117 5.4 Asset Management 120 5.5 Performance Indicators and benchmarks 122 5.6 Financial Ratios 125 5.7 Spending against Capital Budget 131 5.8 Sources of Finance 132 5.9 Capital Expenditure of five largest projects 133 5.10 Cash Flow Management and Investments 135 1 5. 11 Borrowings and Investments 137 5. -

Unrevised Hansard

UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY WEDNESDAY, 28 FEBRUARY 2018 Page: 1 WEDNESDAY, 28 FEBRUARY 2018 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ____ The House met at 15:02. The Speaker took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayer or meditation. CONGRATULATING Ms NALEDI PANDOR (Announcement) The SPEAKER: Hon members, may I take this opportunity to welcome back hon Naledi Pandor to the House and congratulate her for the global acknowledgement for the work she did in the previous portfolio. [Applause.] And also congratulate her for the new portfolio. [Applause.] NOTICES OF MOTION UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY WEDNESDAY, 28 FEBRUARY 2018 Page: 2 The DEPUTY CHIEF WHIP OF THE MAJORITY PARTY: Hon Speaker, I move: That the House - (1) notes the resolution adopted on 6 June 2017, which established the Ad Hoc Committee on the Funding of Political Parties to enquire into and make recommendations on funding of political parties represented in national and provincial legislatures in South Africa with a view to introducing amending legislation if necessary and report by 30 November 2017; (2) the ad hoc committee, in terms of Rule 253(6)(a), ceased to exist after it reported and submitted the Political Party Funding Bill (3) (c) the need for further consideration, inter alia, of the financial implications of the Bill; re-establishes the ad hoc committee with the same composition, membership, chairperson and powers as its predecessor; UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY WEDNESDAY, 28 FEBRUARY 2018 Page: 3 (4) resolves that the ad hoc committee further consider the Political Party Funding Bill upon its referral to the committee; (5) instructs the ad hoc committee to take into account the work done by the previous committee; and; (6) sets the deadline by which the ad hoc committee must report for 30 March 2018. -

General Notices • Algemene Kennisgewings

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 4 No. 42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 GENERAL NOTICE GENERAL NOTICES • ALG EMENE KENNISGEWINGS NOTICEElectoral Commission/….. Verkiesingskommissie OF 2019 ELECTORAL COMMISSION ELECTORALNOTICE 267 COMMISSION OF 2019 267 Electoral Act (73/1998): List of Representatives in the National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures, in respect of the elections held on 8 May 2019 42460 ELECTORAL ACT, 1998 (ACT 73 OF 1998) PUBLICATION OF LISTS OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES IN TERMS OF ITEM 16 (4) OF SCHEDULE 1A OF THE ELECTORAL ACT, 1998, IN RESPECT OF THE ELECTIONS HELD ON 08 MAY 2019. The Electoral Commission hereby gives notice in terms of item 16 (4) of Schedule 1A of the Electoral Act, 1998 (Act 73 of 1998) that the persons whose names appear on the lists in the Schedule hereto have been elected in the 2019 national and provincial elections as representatives to serve in the National Assembly and the Provincial Legislatures as indicated in the Schedule. SCHEDULE This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST Party List Rank ID Name Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC -

Seat Assignment: 2014 National and Provincial Elections

Seat assignment: 2014 National and Provincial Elections Party List Rank Name Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 CHERYLLYN DUDLEY AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Western Cape 1 FERLON CHARLES CHRISTIANS AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS National 1 MANDLENKOSI PHILLIP GALO AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS National 2 LULAMA MAXWELL NTSHAYISA AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS National 3 STEVEN MAHLUBANZIMA JAFTA AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS Provincial: Eastern Cape 1 VUYISILE KRAKRI AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 1 JACOB GEDLEYIHLEKISA ZUMA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 2 MATAMELA CYRIL RAMAPHOSA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 3 KNOWLEDGE MALUSI NKANYEZI GIGABA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 4 GRACE NALEDI MANDISA PANDOR AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 5 JEFFREY THAMSANQA RADEBE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 6 FIKILE APRIL MBALULA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 7 BONGINKOSI EMMANUEL NZIMANDE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 8 BATHABILE OLIVE DLAMINI AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 9 LINDIWE NONCEBA SISULU AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 10 OHM COLLINS CHABANE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 11 MATSIE ANGELINA MOTSHEKGA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 12 EMMANUEL NKOSINATHI MTHETHWA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 13 PRAVIN JAMNADAS GORDHAN AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 14 NOSIVIWE NOLUTHANDO NQAKULA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National -

Vol. 647 15 May 2019 No

Vol. 647 15 May 2019 No. 42460 Mei 2 No.42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 STAATSKOERANT, 15 MEl 2019 No.42460 3 Contents Gazette Page No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS Electoral Commission! Verkiesingskommissie 267 Electoral Act (73/1998): List of Representatives in the National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures, in respect of the elections held on 8 May 2019 ............................................................................................................................ 42460 4 4 No.42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS ELECTORAL COMMISSION NOTICE 267 OF 2019 ELECTORAL ACT, 1998 (ACT 73 OF 1998) PUBLICATION OF LISTS OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES IN TERMS OF ITEM 16 (4) OF SCHEDULE 1A OF THE ELECTORAL ACT, 1998, IN RESPECT OF THE ELECTIONS HELD ON 08 MAY 2019. The Electoral Commission hereby gives notice in terms of item 16 (4) of Schedule 1A of the Electoral Act, 1998 (Act 73 of 1998) that the persons whose names appear on the lists in the Schedule hereto have been elected in the 2019 national and provincial elections as representatives to serve in the National Assembly and the Provincial Legislatures as indicated in the Schedule. SCHEDULE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST Party List Rank ID Name ~urname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 6302015139086 -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/46f8d1/ The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/46f8d1/ I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal ............................................................. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South

VOLUME FIVE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 Analysis of Gross Violations of Findings and Conclusions ........................ 196 Human Rights.................................................... 1 Appendix 1: Coding Frame for Gross Violations of Human Rights................................. 15 Appendix 2: Human Rights Violations Hearings.................................................................... 24 Chapter 7 Causes, Motives and Perspectives of Perpetrators................................................. 259 Chapter 2 Victims of Gross Violations of Human Rights.................................................... 26 Chapter 8 Recommendations ......................................... 304 Chapter 3 Interim Report of the Amnesty Chapter 9 Committee ........................................................... 108 Reconciliation ................................................... 350 Appendix: Amnesties granted............................ 119 Minority Position submitted by Chapter 4 Commissioner -

Annual Report 2011/12

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 / 2012 eThekwini Municipality Contact Details P.O. Box 1014 Email: [email protected] Durban Website: www.durban.gov.za 4000 CONTENTS Page No. Volume One Contents Page 1 Preface 3 Acronyms 4 Chapter One Mayor's Message 7 Municipal Manager's Overview 9 Chapter Two Governance 12 2.1 Introduction to governance 12 2.2 Political governance 12 2.3 Administrative governance 15 2.4 Performance, Monitoring and Evaluation 19 Chapter Three Service Delivery Performance 60 3.1 Introduction 60 3.2 Water Provision 62 3.3 Waste Water (Sanitation) Provision 66 3.4 Electricity Provision 68 3.5 Waste Management 71 3.6 Housing 75 3.7 Roads 78 3.8 Transport 81 3.9 Stormwater Drainage 85 3.10 Local Economic Development ( including Tourism and Markets) 88 3.11 Security and Safety 93 3.12 Disaster Management 95 3.13 Fire and Emergency Services 98 3.14 Development Planning, Environment and Management Unit 100 Chapter Four Organisational Development Performance 104 4.1 Introduction 104 4.2 Employees 105 4.3 Managing the Municipal Workforce 107 4.4 Capacitating the Municipal Workforce 108 4.5 Managing the Workforce Expenditure 109 Chapter Five Financial Performance 110 5.1 Introduction 110 5.2 Statements of Financial Performance 113 5.3 Grants 118 5.4 Asset Management 122 5.5 Performance Indicators and Benchmarks 125 5.6 Financial Ratios 129 5.7 Spending against Capital Budget 137 5.8 Sources of Finance 138 1 5.9 Capital Expenditure of five largest projects 140 5.10 Basic Service and Infrustructure Backlogs - Overview 142 5.11 Cash Flow Management and Investments 144 5. -

Party Name List Type Order Number Idnumber Full Names Surname

National NPE2019 Party name List type Order number IDNumber Full names Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 6302015139086 WAYNE MAXIM THRING AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 4 7403090279083 NOSIZWE ABADA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 5 5602145803084 MOKHETHI RAYMOND TLAELI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 6 5901170249084 JO-ANN MARY DOWNS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 7 5804220857080 KEITUMETSE PATRICIA MATANTE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 8 6802235024083 GRANT CHRISTOPHER RONALD HASKIN AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 9 7810230406089 BERNICE PEARL OSA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 10 7304165540088 MZUKISI ELIAS DINGILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 11 6812205532080 DAVID EUGENE MOSES JOSHUA BARUTI NTSHABELE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 12 8612075246086 BONGANI MAXWELL KHANYILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 13 6108055129089 ANNIRUTH KISSOONDUTH AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 14 8709135113080 MARVIN CHRISTIANS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 15 5403065155088 IVAN JARDINE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 16 6302220199081 LINDA MERIDY YATES AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 17 7905155604088 MONGEZI MABUNGANI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 18 6508220834085 KGOMOTSO