Birds in a Sagebrush Sea: Managing Sagebrush Habitats for Bird Commu- Nities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Assessment for Sage Thrasher (Oreoscoptes Montanus) in Wyoming

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR SAGE THRASHER (OREOSCOPTES MONTANUS ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 1 REBECCA S B USECK , DOUGLAS A. K EINATH , AND MATTHEW H. M CGEE 1 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3023 2 Zoology Program Manager, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3013; [email protected] prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming December 2004 Buseck, Keinath, and McGee – Oreoscoptes montanus December 2004 Table of Contents SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 3 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 4 Morphological Description ...................................................................................................... 4 Taxonomy and Distribution ..................................................................................................... 6 Habitat Requirements............................................................................................................. 8 General .............................................................................................................................................8 -

Plant Guide for Yellow Rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus Viscidiflorus)

Plant Guide valuable forage especially during late fall and early winter YELLOW after more desirable forage has been utilized (Tirmenstein, 1999). Palatability and usage vary between RABBITBRUSH subspecies of yellow rabbitbrush (McArthuer et al., 1979). Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus (Hook.) Nutt. Yellow rabbitbrush provides cover and nesting habitat for Plant Symbol = CHVI8 sage-grouse, small birds and rodents (Gregg et al., 1994). Black-tailed jackrabbits consume large quantities of Contributed by: USDA NRCS Idaho Plant Materials yellow rabbitbrush during winter and early spring when Program plants are dormant (Curie and Goodwin, 1966). Yellow rabbitbrush provides late summer and fall forage for butterflies. Unpublished field reports indicate visitation from bordered patch butterflies (Chlosyne lacinia), Mormon metalmark (Apodemia mormo), mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa), common checkered skipper (Pyrgus communis), and Weidemeyer’s admiral (Limenitis weidemeyerii). Restoration: Yellow rabbitbrush is a seral species which colonizes disturbed areas making it well suited for use in restoration and revegetation plantings. It can be established from direct seeding and will spread via windborne seed. It has been successfully used for revegetating depleted rangelands, strip mines and roadsides (Plummer, 1977). Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description General: Sunflower family (Asteraceae). Yellow rabbitbrush is a low- to moderate-growing shrub reaching mature heights of 20 to 100 cm (8 to 39 in) tall. The stems Al Schneider @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database can be glabrous or pubescent depending on variety, and are covered with pale green to white-gray bark. -

Infection in Kangaroo Rats (Dipodomys Spp.): Effects on Digestive Efficiency

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 55 Number 1 Article 8 1-16-1995 Whipworm (Trichuris dipodomys) infection in kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spp.): effects on digestive efficiency James C. Munger Boise State University, Boise, idaho Todd A. Slichter Boise State University, Boise, Idaho Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Munger, James C. and Slichter, Todd A. (1995) "Whipworm (Trichuris dipodomys) infection in kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spp.): effects on digestive efficiency," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 55 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol55/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 55(1), © 1995, pp. 74-77 WHIPWORM (TRICHURIS DIPODOMYS) INFECTION IN KANGAROO RATS (DIPODOMYS SPP): EFFECTS ON DIGESTIVE EFFICIENCY James C. Mungerl and Todd A. Slichterl ABSTRACT.-To dcterminc whether infections by whipworms (Trichuris dipodumys [Nematoda: Trichurata: Trichuridae]) might affect digestive eHlciency and therefore enel"/,,'Y budgets of two species ofkangaroo rats (Dipodomys microps and Dipodumys urdU [Rodentia: Heteromyidae]), we compared the apparent dry matter digestibility of three groups of hosts: those naturally infected with whipworms, those naturally uninfected with whipworms, and those origi~ nally naturally infected but later deinfected by treatment with the anthelminthic Ivermectin. Prevalence of T. dipodomys was higher in D. rnicrops (.53%) than in D. ordU (14%). Apparent dry matter digestibility was reduced by whipworm infection in D. -

Comodo System Cleaner Version 3.0

Comodo System Cleaner Version 3.0 User Guide Version 3.0.122010 Versi Comodo Security Solutions 525 Washington Blvd. Jersey City, NJ 07310 Comodo System Cleaner - User Guide Table of Contents 1.Comodo System-Cleaner - Introduction ............................................................................................................ 3 1.1.System Requirements...........................................................................................................................................5 1.2.Installing Comodo System-Cleaner........................................................................................................................5 1.3.Starting Comodo System-Cleaner..........................................................................................................................9 1.4.The Main Interface...............................................................................................................................................9 1.5.The Summary Area.............................................................................................................................................11 1.6.Understanding Profiles.......................................................................................................................................12 2.Registry Cleaner............................................................................................................................................. 15 2.1.Clean.................................................................................................................................................................16 -

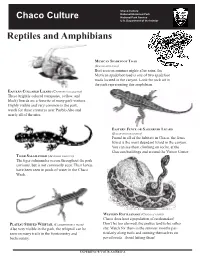

Reptile and Amphibian List RUSS 2009 UPDATE

National CHistoricalhaco Culture Park National ParkNational Service Historical Park Chaco Culture U.S. DepartmentNational of Park the Interior Service U.S. Department of the Interior Reptiles and Amphibians MEXICAN SPADEFOOT TOAD (SPEA MULTIPLICATA) Best seen on summer nights after rains, the Mexican spadefoot toad is one of two spadefoot toads located in the canyon. Look for rock art in the park representing this amphibian. EASTERN COLLARED LIZARD (CROTAPHYTUS COLLARIS) These brightly colored (turquoise, yellow, and black) lizards are a favorite of many park visitors. Highly visible and very common in the park, watch for these creatures near Pueblo Alto and nearly all of the sites. EASTERN FENCE OR SAGEBRUSH LIZARD (SCELOPORUS GRACIOSUS) Found in all of the habitats in Chaco, the fence lizard is the most abundant lizard in the canyon. You can see them climbing on rocks, at the Chacoan buildings and around the Visitor Center. TIGER SALAMANDER (ABYSTOMA TIGRINUM) The tiger salamander occurs throughout the park environs, but is not commonly seen. Their larvae have been seen in pools of water in the Chaco Wash. WESTERN RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS) Chaco does host a population of rattlesnakes! PLATEAU STRIPED WHIPTAIL (CNEMIDOPHORUS VALOR) Don’t be too alarmed, the snakes tend to be rather Also very visible in the park, the whiptail can be shy. Watch for them in the summer months par- seen on many trails in the frontcountry and ticularly along trails and sunning themselves on backcountry. paved roads. Avoid hitting them! EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Amphibian and Reptile List Chaco Culture National Historical Park is home to a wide variety of amphibians and reptiles. -

SA4VBE08KN/12 Philips MP4 Player with Fullsound™

Philips GoGEAR MP4 player with FullSound™ Vibe 8GB* SA4VBE08KN Feel the vibes of sensational sound Small, colorful and entertaining The colored Philips GoGEAR Vibe MP4 player SA4VBE08KN comes with FullSound to bring music and videos to life, and Songbird to synchronize music and enjoy entertainment. SafeSound protects your ears and FastCharge offers quick charging. Superb quality sound • Fullsound™ to bring your MP3 music to life • SafeSound for maximum music enjoyment without hearing damage Complements your life • 4.6 cm/1.8" full color screen for easy, intuitive browsing • Soft and smooth finish for easy comfort and handling • Enjoy up to 20 hours of music or 4 hours of video playback Easy and intuitive • Philips Songbird: one simple program to discover, play, sync • LikeMusic for playlists of songs that sound great together • Quick 5-minute charge for 90 minutes of play • Folder view to organize and view media files like on your PC MP4 player with FullSound™ SA4VBE08KN/12 Vibe 8GB* Highlights FullSound™ level or allow SafeSound to automatically Philips Songbird regulate the volume for you – no need to fiddle with any settings. In addition, SafeSound provides daily and weekly overviews of your sound exposure so you can take better charge of your hearing health. 4.6 cm/1.8" full color screen Philips' innovative FullSound technology One simple, easy-to-use program that comes faithfully restores sonic details to compressed with your GoGear player, Philips Songbird lets MP3 music, dramatically enriching and you discover and play all your media, and sync enhancing it, so you can experience CD music it seamlessly with your Philips GoGear. -

Texosporium Sancti-Jacobi, a Rare Western North American Lichen

4347 The Bryologist 95(3), 1992, pp. 329-333 Copyright © 1992 by the American Bryological and Lichenological Society, Inc. Texosporium sancti-jacobi, a Rare Western North American Lichen BRUCE MCCUNE Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-2902 ROGER ROSENTRETER Bureau of Land Management, Idaho State Office, 3380 Americana Terrace, Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. The lichen Texosporium sancti-jacobi (Ascomycetes: Caliciales) is known from only four general locations worldwide, all in western U.S.A. Typical habitat of Texosporium has the following characteristics: arid or semiarid climate; nearly flat ground; noncalcareous, nonsaline, fine- or coarse-textured soils developed on noncalcareous parent materials; little evidence of recent disturbance; sparse vascular plant vegetation; and dominance by native plant species. Within these constraints Texosporium occurs on restricted microsites: partly decomposed small mammal dung or organic matter infused with soil. The major threat to long-term survival of Texosporium is loss of habitat by extensive destruction of the soil crust by overgrazing, invasion of weedy annual grasses and resulting increases in fire frequency, and conversion of rangelands to agriculture and suburban developments. Habitat protection efforts are important to perpetuate this species. The lichen Texosporium sancti-jacobi (Tuck.) revisited. The early collections from that area have vague Nadv. is globally ranked (conservation status G2) location data while more recent collections (1950s-1960s) by the United States Rare Lichen Project (S. K. were from areas that are now heavily developed and pre- sumably do not support the species. New sites were sought Pittam 1990, pers. comm.). A rating of G2 means in likely areas, especially in southwest Idaho, northern that globally the species is very rare, and that the Nevada, and eastern Oregon. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

F.3 References for Appendix F

F-1 APPENDIX F: ECOREGIONS OF THE 11 WESTERN STATES AND DISTRIBUTION BY ECOREGION OF WIND ENERGY RESOURCES ON BLM-ADMINISTERED LANDS WITHIN EACH STATE F-2 F-3 APPENDIX F: ECOREGIONS OF THE 11 WESTERN STATES AND DISTRIBUTION BY ECOREGION OF WIND ENERGY RESOURCES ON BLM-ADMINISTERED LANDS WITHIN EACH STATE F.1 DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ECOREGIONS Ecoregions delineate areas that have a general similarity in their ecosystems and in the types, qualities, and quantities of their environmental resources. They are based on unique combinations of geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, soils, land use, wildlife, and hydrology (EPA 2004). Ecoregions are defined as areas having relative homogeneity in their ecological systems and their components. Factors associated with spatial differences in the quality and quantity of ecosystem components (including soils, vegetation, climate, geology, and physiography) are relatively homogeneous within an ecoregion. A number of individuals and organizations have characterized North America on the basis of ecoregions (e.g., Omernik 1987; CEC 1997; Bailey 1997). The intent of such ecoregion classifications has been to provide a spatial framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and ecosystem components. The ecoregion discussions presented in this programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) follow the Level III ecoregion classification based on Omernik (1987) and refined through collaborations among U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regional offices, state resource management agencies, and other federal agencies (EPA 2004). The following sections provide brief descriptions of each of the Level III ecoregions that have been identified for the 11 western states in which potential wind energy development may occur on BLM-administered lands. -

Arizona Cliffrose (Purshia Subintegra) on the Coconino National Forest Debra L

Arizona cliffrose (Purshia subintegra) on the Coconino National Forest Debra L. Crisp Coconino National Forest and Barbara G. Phillips, PhD. Coconino, Kaibab and Prescott National Forests Introduction – Arizona cliffrose Associated species Threats Management actions Major range-wide threats to Arizona Cliffrose There are numerous other plant include urbanization, recreation, road and benefiting Arizona cliffrose •A long lived endemic shrub known only from four disjunct populations in species associated with Arizona utility line construction and maintenance, central Arizona, near Cottonwood, Bylas, Horseshoe Lake and Burro cliffrose. These include four Region 3 •Establishment of the Verde Valley Botanical Area minerals exploration and mining, and Creek. Sensitive species: heathleaf wild in 1987 (Coconino National Forest) livestock and wildlife browsing. •Usually less than 2 m tall with pale yellow flowers and entire leaves that buckwheat (Eriogonum ericifolium va r. •Withdrawal of an important part of the ericifolium), Ripley wild buckwheat population from a proposed land exchange lack glands. The Cottonwood population is in a (Eriogonum ripleyi), Verde Valley sage (Coconino National Forest) developing urban/suburban area. The •Occurs only on white Tertiary limestone lakebed deposits of the Verde (Salvia dorrii va r. mearnsii) and Rusby Rusby milkwort population in the Cottonwood area is rapidly •No lands containing Endangered species will be Formation that are high in lithium, nitrates, and magnesium. milkwort (Polygala rusbyi). increasing and human impacts are evident in exchanged from federal ownership (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1995) •Listed as Endangered in 1984. A Recovery Plan was prepared in 1995. the habitat of Arizona cliffrose. Many areas that were “open land” when photographs •Closure of the Botanical Area and surrounding were taken in 1987 are now occupied. -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis