Footfalls OBSTACLE COURSE to LIVABLE CITIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai-Marooned.Pdf

Glossary AAI Airports Authority of India IFEJ International Federation of ACS Additional Chief Secretary Environmental Journalists AGNI Action for good Governance and IITM Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology Networking in India ILS Instrument Landing System AIR All India Radio IMD Indian Meteorological Department ALM Advanced Locality Management ISRO Indian Space Research Organisation ANM Auxiliary Nurse/Midwife KEM King Edward Memorial Hospital BCS Bombay Catholic Sabha MCGM/B Municipal Council of Greater Mumbai/ BEST Brihan Mumbai Electric Supply & Bombay Transport Undertaking. MCMT Mohalla Committee Movement Trust. BEAG Bombay Environmental Action Group MDMC Mumbai Disaster Management Committee BJP Bharatiya Janata Party MDMP Mumbai Disaster Management Plan BKC Bandra Kurla Complex. MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests BMC Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation MHADA Maharashtra Housing and Area BNHS Bombay Natural History Society Development Authority BRIMSTOSWAD BrihanMumbai Storm MLA Member of Legislative Assembly Water Drain Project MMR Mumbai Metropolitan Region BWSL Bandra Worli Sea Link MMRDA Mumbai Metropolitan Region CAT Conservation Action Trust Development Authority CBD Central Business District. MbPT Mumbai Port Trust CBO Community Based Organizations MTNL Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. CCC Concerned Citizens’ Commission MSDP Mumbai Sewerage Disposal Project CEHAT Centre for Enquiry into Health and MSEB Maharashtra State Electricity Board Allied Themes MSRDC Maharashtra State Road Development CG Coast Guard Corporation -

Brihanmumbai Mahanagarpalika

BRIHANMUMBAI MAHANAGARPALIKA PROJECTS SANCTIONED UNDER JNNURM A] IV Mumbai - Middle Vaitarna Water Supply Project :- Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) has undertaken the Middle Vaitarana Water Supply Project, costing Rs.1583.97 crores in order to bring in additional 455 mld water to Mumbai. The Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) of the Central Govt. has approved an expenditure of Rs.1329.50 crores as being admissible for Grant-in-Aid under the JNNURM. The Central and the State Govt. have released the first installment of Rs.33.23 crores for the Middle Vaitarna Water Supply Project. The execution period of the said project is from 2006-07 to 2010-11. The works to be executed under the IV Mumbai Middle Vaitarna Water Supply Project are as follows : 1] Construction of Dam · The proposed Middle Vaitarna Dam on the Vaitarna River has an approximate length of 500 mtrs. and a height of about 100 mtrs. · This will be an R.C.C. (Roller Compacted Concrete) Dam · The water from the Middle Vaitarna Dam will be released into Vaitarna river and will be conveyed upto Modak Sagar Reservoir i.e. upto the Lower Vaitarna Reservoir, through river course. (Implementation status :- Tenders will be received on 15.12.2007) 2] Conveyance and Treatment Works · From Modak Sagar, water will be drawn through a new intake tower in a controlled manner and will be conveyed through a 7.5 km long tunnel upto the Intake Shaft at bell Nalla. (Implementation status :- Agency fixed. Work commenced on the 4th July 2007) · Thereafter water will be brought to the Bhandup Complex via a pipeline of 36 km, in parts, along with the existing 3000 mm. -

Environmental Clearance

Agenda for 89th SEAC-2 meeting scheduled on 20th February, 2019 SEAC Meeting number: 89 Meeting Date February 20, 2019 Subject: Environment Clearance for New Super speciality hospital Building in Dr. D.Y. Patil Hospital Complex located on plot no. 2, Sector 5, Nerul, Navi Mumbai by M/s. Continental Medicare Foundation. Is a Violation Case: No 1.Name of Project New Super speciality hospital Building in Dr. D.Y. Patil Hospital Complex 2.Type of institution Private 3.Name of Project Proponent M/s. Continental Medicare Foundation. 4.Name of Consultant Building Environment India Pvt.Ltd. 5.Type of project Buildings and Constructions 6.New project/expansion in existing project/modernization/diversification Not applicable in existing project 7.If expansion/diversification, whether environmental clearance Not applicable has been obtained for existing project 8.Location of the project D Y Patil Hospital Complex, Plot No – 2, Sector – 5, Nerul, Navi Mumbai 9.Taluka Thane 10.Village Nerul Node Correspondence Name: Dr Anupam Karmarkar Room Number: Administration Department Floor: 3rd floor Building Name: D.Y. Patil Hospital Road/Street Name: na Locality: Nerul City: Navi Mumbai 11.Area of the project Navi Mumbai Concession Layout approved by Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation 12.IOD/IOA/Concession/Plan IOD/IOA/Concession/Plan Approval Number: LOI dated 20.06.2018, Vide Letter NMMC/ Approval Number TPO/ ADTP/2495/2018 Approved Built-up Area: 92500 Dr. D.Y. Patil Hospital and Research Centre was founded in 2004 over an area of 60000 sq.mt. The hospital has 1500 beds, 100 bed ICU, 15 bed operation theatre, 24x7 charitable casualty and trauma centre. -

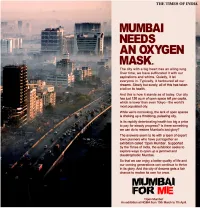

Open Spaces Help Social Networking

TIMES CITY >> Creating open spaces THE TIMES OF INDIA, MUMBAI | SATURDAY, MARCH 10, 2012 LAYOUT RECREATION GROUNDS | FORTS & HISTORIC PRECINCTS | HILLS & FORESTS | CITY FORESTS | PEOPLE-FRIENDLY RAILWAY STATIONS | AREA NETWORKING ‘ HELP SOCIAL NETWORKING’ OPEN SPACES Uma Kadam TIMES NEWS NETWORK Cross Maidan gets a clean, mean look Hemant Shirodkar magine being able to walk or cycle from Mal- ad to Colaba or Chem- bur to south Mumbai along well-maintained walking-and-cyclingI tracks, with gardens and parks to view or rest in along the way. Maybe you could even stop by a beach. Sounds unreal, especially in a city like Mum- bai, which offers an abysmal amount of open space to its 12.4 million residents. Before But this is one of the longer-term goals of the Open Mumbai plan being promoted by city architect P t was a long-drawn battle K Das and his team, who for residents of Churchgate seek to change the way Mum- Ito get the authorities to take bai deals with open spaces. note of four acres of Cross After The plan may sound fanciful Maidan that had turned into but a year of research, doc- a no-man’s land. The space that umentation, mapping and was encroached upon and ren- collating statistics has gone dered absolutely unusable be- Cross-Over To Beauty into developing a vision that came a sanctuary for residents in June 2010. Nearly four acres G For years, Cross Maidan remained encroached upon, its seeks to place “people and of Cross Maidan near Church- fences were broken and it was rendered unusable community life at the centre gate at one end of Fashion Str- G The maidan’s beautification was conceptualized by the of planning, not real estate eet was thrown open to public. -

Open Mumbai Media Coverage

BENNETT, COLEMAN & CO. LTD. | ESTABLISHED 1838 | TIMESOFINDIA.COM | EPAPER.TIMESOFINDIA.COM MUMBAI | SATURDAY, MARCH 10, 2012 | PAGES 50 * PRICE ` 5.00 ALONG WITH MUMBAI MIRROR OR THE ECONOMIC TIMES OR MAHARASHTRA TIMES * DRAVID’S Tests, runs, second catches in Tests, highest for a Test hundreds, centuries abroad, next third highest by any 210non-wicketkeeper fourth highest 21 only to Sachin’s 29 FAB FEATS highest 13,288Test batsman, 36after Tendulkar by any at an average of 52.31. Better average balls faced in Tests, (51), Jacques Kallis (42) Tests as captain of India; Rahul Dravid announces his player overseas (53.03) than at home (51.35) more than any batsman and Ricky Ponting (41) 8 won, 6 lost and 11 drawn retirement on Friday 164 31,189 25 ONE INNINGS ENDS AT 39, ANOTHER SET TO BEGIN AT 38 Finally, I would like to thank the Indian cricket fan. The game is lucky to have you and I have been lucky to play before you. To represent India, and you, “has been a privilege and one which I have always taken seriously. My Mulayam firm: Akhilesh to be CM approach to cricket was simple. It was about giving everything to the team, playing with dignity, and upholding the spirit of the game. I have failed at Azam Khan and Shivpal sta- Works On keholders in this key deci- Violence up, times, but I have never stopped trying. It is why... sion, and they will be reward- Azam, Shivpal ed with plum posts. big test for One compromise formu- la doing the rounds has Az- I leave with sadness To Back Son am Khan being made the Spe- new leader Pervez Iqbal Siddiqui TNN aker, which would ensure the TIMES NEWS NETWORK senior leader does not have Lucknow: A day before the to report to Akhilesh. -

00:25:27.930 Nikhil Anand: Thanks, Everyone, Very Much for Joining Us Today

242 00:25:14.250 --> 00:25:27.930 Nikhil Anand: Thanks, everyone, very much for joining us today. It's really wonderful to have as many people joining us from different parts of the world between Mumbai and here in Philadelphia. 243 00:25:29.040 --> 00:25:41.280 Nikhil Anand: My name is Nikhil Anand and I'm an Associate Professor of Anthropology here at the University of Pennsylvania, and I'm here with Anuradha Mathur, who is a professor of landscape architecture at the Weitzman school of Design, also here at the University of Pennsylvania. We're pleased to be moderating the first event of Inhabited Sea projects, titled, “Living with Rain.” We invite you to briefly introduce yourself; Your name, affiliations and your interests, perhaps that bring you to this event in the chat box. Ordinarily would have liked to have had an open conversation around our works, but the numbers today don't permit that to happen. 248 00:26:15.660 --> 00:26:33.510 Nikhil Anand: In January of 2019, with support from Penn's Global India Research Engagement Fund, we launched Inhabited Sea; a trans-disciplinary research initiative that seeks to imagine or reimagine Mumbai from what is its relentlessly wet terrain. 249 00:26:34.650 --> 00:26:38.040 Nikhil Anand: In doing this, we wanted to rethink the city with the provocations that were generated in Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha’s book, Soak. Published in 2009 after Mumbai's floods the book made a series of interventions demanding we reimagine the city and it's futures from a terrain of wetness. -

Current Affairs Questions and Answers for February 2010: 1. Which Bollywood Film Is Set to Become the First Indian Film to Hit T

ho”. With this latest honour the Mozart of Madras joins Current Affairs Questions and Answers for other Indian music greats like Pandit Ravi Shankar, February 2010: Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayak and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt who have won a Grammy in the past. 1. Which bollywood film is set to become the first A. R. Rahman also won Two Academy Awards, four Indian film to hit the Egyptian theaters after a gap of National Film Awards, thirteen Filmfare Awards, a 15 years? BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe. Answer: “My Name is Khan”. 9. Which bank became the first Indian bank to break 2. Who becomes the 3rd South African after Andrew into the world’s Top 50 list, according to the Brand Hudson and Jacques Rudoph to score a century on Finance Global Banking 500, an annual international Test debut? ranking by UK-based Brand Finance Plc, this year? Answer: Alviro Petersen Answer: The State Bank of India (SBI). 3. Which Northeastern state of India now has four HSBC retain its top slot for the third year and there are ‘Chief Ministers’, apparently to douse a simmering 20 Indian banks in the Brand Finance® Global Banking discontent within the main party in the coalition? 500. Answer: Meghalaya 10. Which country won the African Cup of Nations Veteran Congress leader D D Lapang had assumed soccer tournament for the third consecutive time office as chief minister on May 13, 2009. He is the chief with a 1-0 victory over Ghana in the final in Luanda, minister with statutory authority vested in him. -

Maximum Marks: 100 QP Code-32366 Q.1.A. A) Mahim Creek B)Powai Lake C) Juhu Beach, Aksa Beach Etc. D) Sides of Mahim Creem, Malad, Creek, Manori Creek, Etc

Maximum Marks: 100 QP Code-32366 Q.1.A. a) Mahim Creek b)Powai lake c) Juhu Beach, Aksa beach etc. d) Sides of Mahim Creem, Malad, Creek, Manori Creek, Etc. e) Mahim Nature Park or any other f) Haji Ali, Mahalakshmi, Siddhivinayak or any other religious place g) Near Air Port or any noise pollution site. h) Malabar hill i) Mithi River, Poisar river etc. j) Deonar, Kanjurmarg etc. Q. 1. B. a) Ratnagiri District b) Sindhudurg Fort or any other c) Tarapur d) Jawhar, Matheran, Amboli etc. e) Bordi, Dahanu, Kelwa or any other beach in Palghar District f) Thane, Kalyan or any other g) Vasai Creek h) Nearby river or any flood prone area can be located. i) Any site can be located (landslide in ghats) j) Vajreshwari or any other. Q.2A. Sources of Waste: House or Residence, Industry, Market, Shopping Mall, Agricultural Field, Constructional Site, Any Institution, Hospital and Clinic etc with example B. Impacts of waste on environment • Solid waste contaminates water, air, land etc. • Can choke drains • Burning of wastes creates air pollution • Radioactive waste materials having impact on soil livestock etc. • Due to pollution processes of photosynthesis obstructed • Dumping of wastes spread foul smell and results in to different disease etc. OR C. Role of Citizens in Waste Management • Citizen can adopt eco-friendly lifestyle • They can create sustainable society • Segregation of waste at source • Adoption of conservation practice • Buyback policy etc 1 D. Efforts made by MCGM in Management of Waste • Public participation: Advance locality management • Clean-up marshals • Slum Adoption program • Create public awareness campaign through information, education and communication strategy • Development of sustainable society with zero waste etc Q.3 A. -

Mumbai's Open Spaces Data

MUMBAI’S OPEN SPACES Maps & A Preliminary Listing Document Prepared by Contents Introduction........................................................2 H(W) ward........................................................54 Mumbai's Open Spaces Data..............................4 K(E) ward.........................................................60 Mumbai's Open Spaces Map...............................5 K(W) ward........................................................66 Mumbai's Wards Map..........................................7 P(N) ward.........................................................72 P(S) ward.........................................................78 City - Maps & Open Spaces List ----------------------------------------------------------------- R(N) ward.........................................................84 A ward................................................................8 R(C) ward.........................................................90 B ward..............................................................12 R(S) ward.........................................................96 C ward..............................................................16 D ward..............................................................20 Central & Eastern - Maps & Open Spaces List ----------------------------------------------------------------- E ward..............................................................24 L ward............................................................100 F(N) ward.........................................................30 -

CHILDREN Saturday

Saturday - 4th Feb: Kala Ghoda Schedule CHILDREN Title Location Time Description Methodical Max Mueller 11.00 am - Workshop in Origami with CSA By Bhavan Gate 01.00 pm Nilesh Shaharkar Special Workshop For Special Max Mueller 11.00 am - Ami Kothari in a creative session with Children Bhavan Gate 12.00 pm Little Angel Foundation. (children with mental disabilities) Post Office Adventures Entrance Gate 2.30 pm - Mumbai GPO is the biggest Post of GPO, Fort 3.30 pm Office in the country and one of the biggest in the world! Join Kruti as she takes you on a tour through this magnicificent structure. (ages 8 - 13) Speak with Paper Max Mueller 3.30 pm - Paper bag decoration with recycled Bhavan Gate 5.30 pm paper by Amruta Pathre (ages 9 - 15) Wonderful Wire Craft Max Mueller 4.00 pm - Watch and learn with Colaba's street Bhavan Gate 5.00 pm artist Harish. (9 yrs & above) Hanging Gardens Max Mueller 5.30 pm - Creating fresh flower hanging Bhavan Gate 7.00 pm arrangements with roots ribbons and crystals with Vibha Gupta (ages 10 - 15) [NOTE: Kids section can get crowded on the Weekends] www.wonderfulmumbai.com FOOD Title Location Time Description Asian Chef of the year 5 All Day, Hotel 4.00 pm - Embark on a 'food-art' journey with Milind Milind Sovani and Apollo, Colaba 6.00 pm and Asha as they give you priceless tips on Asha Khatau Causeway eyecatching presentations of Indian cuisine. www.wonderfulmumbai.com FILM Title Location Time Description REGIONAL GEMS Adaminte Makan Abu Max Mueller 2.30 pm - India’s Entry for the Oscars is about an Malayalam (101 min) Bhavan 4.30 pm elderly couple yearning to go on Haj. -

Visceral Politics of Food: the Bio-Moral Economy of Work- Lunch in Mumbai, India

Visceral politics of food: the bio-moral economy of work- lunch in Mumbai, India Ken Kuroda London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2018 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98896 words. 2 Abstract This Ph.D. examines how commuters in Mumbai, India, negotiate their sense of being and wellbeing through their engagements with food in the city. It focuses on the widespread practice of eating homemade lunches in the workplace, important for commuters to replenish mind and body with foods that embody their specific family backgrounds, in a society where religious, caste, class, and community markers comprise complex dietary regimes. Eating such charged substances in the office canteen was essential in reproducing selfhood and social distinction within Mumbai’s cosmopolitan environment. -

Mumbai's Pedestrian Paradox

According to the recent [and Institute, an independent organisation may be required in some areas, but the only] comprehensive transport working on urban planning issues. 1 these should not be replicated all over. survey (CTS) 2005-08 of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Whereas MMRDA is going Skywalks Authority (MMRDA), over 52 per cent full force in implementing various Skywalk is an elevated walk of Mumbaikars make their average infrastructure projects in Mumbai, way dedicated to the pedestrians. daily trips by walking. Another 25 per such as Metro rail, monorail, sea links, It connects the railway station/high cent use the local trains, whereas 12 expressways, flyovers, etc, providing concentration commercial area with the per cent average daily trips are made basic pedestrian infrastructure such as destination points where concentration through public transport buses. And footpaths is not on its agenda. No wonder of pedestrians prevails. The purpose in sharp contrast to these figures, the then that the new business districts of of skywalks is efficient dispersal of share of private vehicles’ (read cars) the city have no provision for walking. commuters from station/congested area in percentage average trips per day is “Business districts like Powai, Bandra- to strategic locations viz. bus stops, taxi barely 3 per cent. Mumbai thus clearly Kurla Complex, Andheri East, Mindspace stands, shopping areas, off roads etc. and seems to be having an edge over in Malad, etc. have been developed vice versa.Keeping these facts in mind, the other Indian motorized cities. only for people who come in their fast MMRDA has planned 50 skywalks in the moving cars.