Louise Johnson/PCOL MIRIAM – Exodus 2:4-8; 15:20-21; Numbers 12:1-16 – Kathleen Mcvey Main Points with Discussion Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missing Pieces Report: the 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women

alliance for board diversity Missing Pieces Report: The 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards Missing Pieces Report: The 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards About the Alliance for Board Diversity Founded in 2004, the Alliance for Board Diversity (ABD) is a collaboration of four leadership organizations: Catalyst, The Executive Leadership Council (ELC), the Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility (HACR), and LEAP (Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics). Diversified Search, an executive search firm, is a founding partner of the alliance and serves as an advisor and facilitator. The ABD’s mission is to increase the representation of women and minorities on corporate boards. More information about ABD is available at www.theabd.org. About Deloitte In the US, Deloitte LLP and Deloitte USA LLP are member firms of DTTL. The subsidiaries of Deloitte LLP provide industry- leading audit & assurance, consulting, tax, and risk and financial advisory services to many of the world’s most admired brands, including more than 85 percent of the Fortune 500 and more than 6,000 private and middle market companies. Our people work across more than 20 industry sectors with one purpose: to deliver measurable, lasting results. We help reinforce public trust in our capital markets, inspire clients to make their most challenging business decisions with confidence, and help lead the way toward a stronger economy and a healthy society. As part of the DTTL network of member firms, we are proud to be associated with the largest global professional services network, serving our clients in the markets that are most important to them. -

Missing Pieces Report: the Board Diversity Census of Women And

Missing Pieces Report: The Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards, 6th edition Missing Pieces Report: The Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards, 6th edition About the Alliance for Board Diversity Founded in 2004, the Alliance for Board Diversity (ABD) is a collaboration of four leadership organizations: Catalyst, the Executive Leadership Council (ELC), the Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility (HACR), and Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics (LEAP). Diversified Search Group, an executive search firm, is a founding partner of the alliance and serves as an advisor and facilitator. The ABD’s mission is to enhance shareholder value in Fortune 500 companies by promoting inclusion of women and minorities on corporate boards. More information about ABD is available at theabd.org. About Deloitte Deloitte provides industry-leading audit, consulting, tax and advisory services to many of the world’s most admired brands, including nearly 90% of the Fortune 500® and more than 7,000 private companies. Our people come together for the greater good and work across the industry sectors that drive and shape today’s marketplace — delivering measurable and lasting results that help reinforce public trust in our capital markets, inspire clients to see challenges as opportunities to transform and thrive, and help lead the way toward a stronger economy and a healthier society. Deloitte is proud to be part of the largest global professional services network serving our clients in the markets that are most important to them. Now celebrating 175 years of service, our network of member firms spans more than 150 countries and territories. -

Daniel 1. Who Was Daniel? the Name the Name Daniel Occurs Twice In

Daniel 1. Who was Daniel? The name The name Daniel occurs twice in the Book of Ezekiel. Ezek 14:14 says that even Noah, Daniel, and Job could not save a sinful country, but could only save themselves. Ezek 28:3 asks the king of Tyre, “are you wiser than Daniel?” In both cases, Daniel is regarded as a legendary wise and righteous man. The association with Noah and Job suggests that he lived a long time before Ezekiel. The protagonist of the Biblical Book of Daniel, however, is a younger contemporary of Ezekiel. It may be that he derived his name from the legendary hero, but he cannot be the same person. A figure called Dan’el is also known from texts found at Ugarit, in northern Syrian, dating to the second millennium BCE. He is the father of Aqhat, and is portrayed as judging the cause of the widow and the fatherless in the city gate. This story may help explain why the name Daniel is associated with wisdom and righteousness in the Hebrew Bible. The name means “God is my judge,” or “judge of God.” Daniel acquires a new identity, however, in the Book of Daniel. As found in the Hebrew Bible, the book consists of 12 chapters. The first six are stories about Daniel, who is portrayed as a youth deported from Jerusalem to Babylon, who rises to prominence at the Babylonian court. The second half of the book recounts a series of revelations that this Daniel received and were interpreted for him by an angel. -

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title the Jews used in their Hebrew Old Testament for this book comes from the fifth word in the book in the Hebrew text, bemidbar: "in the wilderness." This is, of course, appropriate since the Israelites spent most of the time covered in the narrative of Numbers in the wilderness. The English title "Numbers" is a translation of the Greek title Arithmoi. The Septuagint translators chose this title because of the two censuses of the Israelites that Moses recorded at the beginning (chs. 1—4) and toward the end (ch. 26) of the book. These "numberings" of the people took place at the beginning and end of the wilderness wanderings and frame the contents of Numbers. DATE AND WRITER Moses wrote Numbers (cf. Num. 1:1; 33:2; Matt. 8:4; 19:7; Luke 24:44; John 1:45; et al.). He apparently wrote it late in his life, across the Jordan from the Promised Land, on the Plains of Moab.1 Moses evidently died close to 1406 B.C., since the Exodus happened about 1446 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1), the Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years (Num. 32:13), and he died shortly before they entered the Promised Land (Deut. 34:5). There are also a few passages that appear to have been added after Moses' time: 12:3; 21:14-15; and 32:34-42. However, it is impossible to say how much later. 1See the commentaries for fuller discussions of these subjects, e.g., Gordon J. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

Solitary Confinement, Public Safety, and Recdivism

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 47 2014 Solitary Confinement, Public Safety, and Recdivism Shira E. Gordon University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Shira E. Gordon, Solitary Confinement, Public Safety, and Recdivism, 47 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 495 (2014). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol47/iss2/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLITARY CONFINEMENT, PUBLIC SAFETY, AND RECIDIVISM Shira E. Gordon* As of 2005, about 80,000 prisoners were housed in solitary confinement in jails and in state and federal prisons in the United States. Prisoners in solitary confine- ment are generally housed in a cell for twenty-two to twenty-four hours a day with little human contact or interaction. The number of prisoners held in solitary con- finement increased 40 percent between 1995 and 2000, in comparison to the growth in the total prison population of 28 percent. Concurrently, the duration of time that prisoners spend in solitary confinement also increased: nationally, most prisoners in solitary confinement spend more than five years there. -

A Biographical Study of Aaron

Scholars Crossing Old Testament Biographies A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible 10-2018 A Biographical Study of Aaron Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "A Biographical Study of Aaron" (2018). Old Testament Biographies. 4. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Old Testament Biographies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aaron CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY I. His service A. For Moses 1. Aaron was a spokesman for Moses in Egypt. a. He was officially appointed by God (Exod. 4:16). b. At the time of his calling he was 83 (Exod. 7:6-7). c. He accompanied Moses to Egypt (Exod. 4:27-28). d. He met with the enslaved Israelites (Exod. 4:29). e. He met with Pharaoh (Exod. 5:1). f. He was criticized by the Israelites, who accused him of giving them a killing work burden (Exod. 5:20-21). g. He cast down his staff in front of Pharaoh, and it became a serpent (Exod. 7:10). h. He saw his serpent swallow up the serpents produced by Pharaoh's magicians (Exod. 7:12). i. He raised up his staff and struck the Nile, causing it to be turned into blood (Exod. -

Resurrection Or Miraculous Cures? the Elijah and Elisha Narrative Against Its Ancient Near Eastern Background

Bar, “Resurrection or Miraculous Cures?” OTE 24/1 (2011): 9-18 9 Resurrection or Miraculous Cures? The Elijah and Elisha Narrative Against its Ancient Near Eastern Background SHAUL BAR (UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS) ABSTRACT The Elijah and Elisha cycles have similar stories where the prophet brings a dead child back to life. In addition, in the Elisha story, a corpse is thrown into the prophet’s grave; when it comes into con- tact with one of his bones, the man returns to life. Thus the question is do these stories allude to resurrection, or “only” miraculous cures? What was the purpose of the inclusion of these stories and what message did they convey? In this paper we will show that these are legends that were intended to lend greater credence to prophetic activity and to indicate the Lord’s power over death. A INTRODUCTION There is consensus among scholars that Dan 12:2-3, which they assign to the 1 second century B.C.E., refers to the resurrection of the dead. The question be- comes whether biblical texts earlier than this era allude to this doctrine. The phrase “resurrection of the dead” never appears in the Bible. Scholars searching for biblical allusions to resurrection have cited various idioms.2 They list verbs including “arise,”3 “wake up,”4 and “live,”5 all of which can denote a return to life. We also find “take,”6 which refers to being taken to Heaven, the noun “life,”7 and “see.”8 In the present paper however, we shall examine the stories of the Elijah and Elisha cycles which include similar tales in which the prophet brings a dead child back to life: in Elijah’s case, the son of the widow of Zare- phath (1 Kgs 17:17-24); in Elisha’s, the son of the Shunammite matron (2 Kgs 4:31-37). -

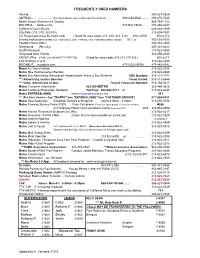

FREQUENTLY USED NUMBERS Access 800-827-0829 AMTRAK…

FREQUENTLY USED NUMBERS Access 800-827-0829 AMTRAK….. ………….. (For Union Station only: Lost/Found 213-683-6897)……. 800-USA-RAIL…….. …..800-872-7245 Beach Buses (Summer-LA County) 888-769-1122 BOLTBUS … boltbus.com 877-BOLTBUS…… 877-265-8287 Children's Court Shuttle 626-458-3909 City Ride (213, 310, 323,818) 213-808-7433 CX Passes purchase by credit card) ( Good for area codes 213, 310, 323, 818) 808-CARD 808-2273 Driving Instructions (TellMe,Voice Automated..state: "TRAVEL", then "DRIVING DIRECTIONS") 511 or 800-555-8355 Foothill Transit Office 800-743-3463 Greyhound (Any city) 800-231-2222 Graffiti Removal 213-922-5860 Hollywood Bowl Shuttle 323-850-2000 LADOT office (DASH and COMMUTER EXPRESS) (Good for area codes 818,213,310,323 ) 808-2273 LAX Shuttles C & G 310-646-2250 MEGABUS …megabus.com 877-GO2-MEGA…. 877-462-6342 Metro Art Tours Hotline 213-922-2738 Metro Bike Hotline/Locker Rentals 213-922-2660 Metro Bus Advertising (Ads placed inside/outside of bus & Bus Shelters) CBS Outdoor: 323-222-7171 *** Advertising on Bus Benches Coast United: 818-313-8644 *** Video Advertising on Bus Transit Television Network: 818-768-0617 Metro Customer Information 323-GO-METRO 323-466-3876 Metro Customer/Passenger Relations Toll Free 800-464-2111 or 213-922-6235 Metro EXPRESSLANES www.metroexpresslanes.net 511 *** (For Cust. Service - Say "TRAFFIC" then "EXPRESSLANES" then "CUSTOMER SERVICE") 877-224-6511 Metro Fare Reduction (Disabled, Seniors & Students) Hours 8:00am - 4:00pm 213-680-0054 Metro Freeway Service Patrol (FSP) From Cell phone: Press -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

The Book of Daniel Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character

G. Ch. Aalders, “The Book of Daniel: Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character,” The Evangelical Quarterly 2.3 (July 1930): 242-254. The Book of Daniel Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character G. Ch. Aalders [p.242] In the January issue of this periodical I endeavoured to throw light upon the turn of the tide which has been accomplished in Pentateuchal criticism during the last decennia. I now want to draw the attention of our readers to another problem of the Old Testament which has been of no less importance in negative Bible criticism. The vast majority of Old Testament students have been wont to deny to the Book of Daniel any historical value and to dispute its real prophetic character. In the case of this book it again was regarded as one of the most certain and unshakable results of scientific research, that it could not have originated at an earlier date than the Maccabean period, and, therefore, neither be regarded as a trustworthy witness to the events it mentions, nor be accepted as a proper prediction of the future it announces. Now as to this date, criticism certainly is receding; and this retreat is characterised by the fact that, in giving up the unity of the book, for some parts a considerably higher age is accepted. Meinhold took the lead: he separated the narrative part (chs. ii-vi) from the prophetic part (chs. vii-xii), and leaving the latter to the Maccabean period claimed for the former a date about 300 B.C.1 Various scholars followed, e.g. -

Elisha the Life & Times of Elisha We Know Next to Nothing About Elisha’S Early Life Until Sometime Around the Year 856 BC, When He Was Probably in His Twenties

Elisha The Life & Times of Elisha We know next to nothing about Elisha’s early life until sometime around the year 856 BC, when he was probably in his twenties. He appears to have come from a wealthy land owning family, if the number of oxen they had for ploughing is anything to go by (1 Kings 19:19). When the prophet Elijah arrived suddenly his response to his call was immediate. Elijah made it clear that it was up to him whether or not he responded to God’s call when Elisha asked permission to say farewell to his parents. To demonstrate his determination to follow Elisha dramatically severed his links to his past life by slaughtering the pair of oxen he was ploughing with and cooked their meat over the wood of his plough and gave it to his friends and relatives. Scripture tells us that he then left and became Elijah’s attendant or servant in similar way, perhaps, to that in which Joshua had served Moses (cf. Exod. 24:13; 33:11; Num. 11:28). We hear nothing more of Elisha for at least the next four years, but we can assume that he faithfully served Elijah during that period and learned from him. Knowing that the Lord was about to take him Elijah tested his servant’s devotion by asking him three times to remain while he went on in turn to Bethel (2 Kings 2:2), Jericho (2:4) and then over the Jordan (2:6). Elisha and the other prophets of the Lord were well aware of what was about to happen and he refused to leave his master.