Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As a Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tickets Delayed Relocation

TICKETS RELOCATION DELAYED Digital dismissal system Merritt encourages bypass Whiteville High School’s for traffic violations businesses to move downtown Legion Stadium field house going online. when widening begins. project running late. uuSEE 4A uuSEE 2A uuSEE 3A The News Reporter Published since 1890 every Monday and Thursday for the County of Columbus and her people. WWW.NRCOLUMBUS.COM Monday, July 25, 2016 75 CENTS SLICE TWICE ... SLICE THRICE ... SLICE NICE WESTERN PRONG PRECINCT MOVE IN MONDAY MEETING Elections board to consider new voting machines By Allen Turner [email protected] The Columbus County Board of Elections will meet to- day at 5 p.m. to consider purchasing new voting equipment to be used throughout the county. A new polling site for the Western Prong precinct is also under consideration. The board is expected to approve the purchase of 42 new voting machines at $245,000. The new machines would be in use by the November General Election. Michelle Mrozkowski of New Bern-based vendor Print- Elect demonstrated the new voting machines Friday for Board of Elections members and the public. The DS200 precinct scanner and tabulator would re- place older machines in use in Columbus County since 2006. When a voter casts his or her ballot, the new machine will be able to detect whether the voter has undervoted (by not voting in all races or by not voting for as many candidates as possible in a race) or overvoted (by voting for too many candidates in a race). The voter will be alerted by the machine and given the choice of either casting the ballot as marked or returning Staff photo by ALLEN TURNER A machete-weilding volunteer makes short work of preparing watermelon samples during Saturday’s N.C. -

Say Yes to the Text

Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, Vol. 5, No.1/2, 2015, pp. 42-49. Say Yes to the Text Jennifer Burg In this essay, the author describes her experience as a participant in the reality television show Say Yes to the Dress. She delves into the production aspects of the show and her own feelings of identification with the production staff. She also considers the multiple audiences, both present and not present, in applying for, producing, and par- ticipating in a reality television show. Keywords: Audience, Autoethnography, Bridal Rituals, Femininity, Reality Television, Wedding Rituals Proposal For years when we were single, my best friend Jackie and I would come home from late nights out in NYC, climb into her bed with bowls of cereal, and watch TV until we fell asleep. Our fa- vorites were shows that aired on TLC, and of those we most loved Say Yes to the Dress. We took great pleasure in watching the brides-to-be try on, reject and select their dream dresses in the sparkly showroom of Kleinfeld, in the heart of Manhattan. We critiqued every ensemble, mar- veled at every price point, and added our own snarky commentary to that of the friends and fami- ly who came along to assist the soon-to-be-wed. We scrutinized everything from the tiaras to the toe clips and the whole lot in between. We had our favorite designers, and we knew the Kleinfeld consultants by name. Never did we think that we might actually have the experience that we so often watched: Jackie has two kids and is divorced; I was engaged once years ago, but that didn’t work out. -

Wiarnon How Do You Cook Leg of Lamb?

A A. PAGE TWENTY-F0UR\ i ' THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 1969 ■ N ilanirlTPBtrr lEtiming fcralii ^ AviNage Dsily Net Press Run 9 m The W e e k M M Thp Weather VFW Auxiliary will hold a An open house will be held for A m 38, U M Cloudy with chance of drizzle About Town rummage sale next Wednesday Mi^ and Mrs. Thomas Albro, GOP Lead 35 Weiss Teaches at the poet home. Members may through Saturday noon. Low to formerly of 80 Winter St., on St. Bridget R o s a ^ Society bring articles for sAle to the Manchester • Democrats Course at MCC a s , 4 5 9 night in _the 60s. ’Tom onow’s will have its annual installation meeting Tuesday. Those wish Sunday from 2:30 to 8 p.m., at continue to cut Into the R e high in the 7Da. 'v Town Manager Robert Weiss banquet Sept. 16 , at 6:30 p.m. ing to have articles picked up tlve home of their daughter and publican lead in registered,, Manehemter— A City of Pillage Charm started teaching a class la.t at W illie’s Steak House. Reser may call Mrs. Florence Plltt of son-ln-Iaw, Mr. and MrSj_ Jack voters, and the GOP margin, 816 Main St. night at Manchester Community VOL. LXXXVm. NO. 286 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) vations will close Monday. The Krafjack, . 100 Meadow Lark as of today,; is dofVn to 35, How do You MANCHESTER, OONN, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1969 / (C A M e m e M s m P li«e M ) College, and will conduct the PRICE TEN CENTS Rev. -

P32 Layout 1

THURSDAY, JUNE 18, 2015 TV PROGRAMS 05:05 E!ES Jimmy Fallon 06:00 Keeping Up With The 13:00 Late Night With Seth Meyers Kardashians 14:00 The Goldbergs 06:55 Keeping Up With The 14:30 2 Broke Girls Kardashians 15:00 2 Broke Girls 01:00 Stolen Child-PG15 00:15 Come Dine With Me 07:50 Style Star 15:30 The Daily Show With Jon 03:00 Draft Day-PG15 00:40 Kirstie’s Best Of Both Worlds 08:20 E! News Stewart 05:00 The Butler-PG15 01:25 Tareq Taylor’s Nordic 09:15 Giuliana & Bill 16:00 The Nightly Show With Larry 07:15 See Girl Run-PG15 Cookery 10:15 Giuliana & Bill Wilmore 09:00 Five Thirteen-PG15 01:55 Masterchef: The 11:10 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 17:00 Late Night With Seth Meyers 10:45 The Butler-PG15 Professionals 11:35 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 18:00 Hot In Cleveland 13:00 Mandela: Long Walk To 02:45 Bargain Hunt 12:05 E! News 18:30 The Goldbergs Freedom-PG15 03:40 Tareq Taylor’s Nordic 13:05 Christina Milian Turned Up 19:00 Two And A Half Men 15:30 Robot & Frank-PG15 Cookery 13:35 Christina Milian Turned Up 19:30 Community 17:00 Five Thirteen-PG15 04:05 Bargain Hunt 14:05 Extreme Close-Up 20:00 The Tonight Show Starring 19:00 Philomena-PG15 04:55 Rachel Khoo’s Kitchen 14:30 Style Star Jimmy Fallon 21:00 The Trials Of Cate McCall- Notebook: London 15:00 Keeping Up With The 21:00 The Daily Show With Jon 23:00 Prisoners-PG15 05:25 Tareq Taylor’s Nordic Kardashians Stewart Cookery 16:00 Keeping Up With The 21:30 The Nightly Show With Larry 05:50 Come Dine With Me Kardashians Wilmore 06:15 Homes Under The Hammer 17:00 Fashion Bloggers 22:00 Modern Family 07:10 Homes Under The Hammer 17:30 Fashion Bloggers 22:30 Black-Ish 08:00 Come Dine With Me 18:00 E! News 23:00 The Simpsons 01:30 The Fifth Estate 08:30 Antiques Roadshow 19:00 E!ES 23:30 Late Night With Seth Meyers 04:00 Mr. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Nancy Daniels President and General Manager, TLC

Nancy Daniels President and General Manager, TLC As President and General Manager of TLC, Daniels leads the company’s flagship female focused channel, a global brand available in more than 90 million homes nationally and 271 million households around the world. Daniels oversees all aspects of the network’s programming, production, development, multiplatform, communications and marketing in the US. Daniels is the most senior female content executive at Discovery Communications, which reaches 3 billion cumulative viewers across pay-TV and free-to-air platforms in more than 220 countries. Based in the company’s Los Angeles office, she’s held this position since September 2013. Amid ever more fierce competition for audience, Daniels has maintained TLC’s reign as a top 10 network for women with long running hit series Sister Wives, The Little Couple, My 600-lb Life, Return to Amish, Kate Plus 8, 90 Day Fiancé as well as new series 90 Day Fiancé: Happily Ever After?, Long Lost Family, The Spouse House and OutDaughtered. Of the 19 returning series in 2017 to-date, 17 are up or on par versus their previous season. In addition, TLC continues to show strong growth finishing out third quarter 2017 up 19% in primetime versus year ago and ranked as the #6 ad-supported cable network among W25-54. This year, TLC made a major announcement under the helm of Daniels, bringing back original home design series TRADING SPACES after ten years, with Paige Davis returning as host. As one of the most beloved TLC shows that started the home makeover craze, viewers will watch as families and neighbors hand over the keys to their home and let the renovation fun begin. -

P32.Qxp Layout 1

TUESDAY, AUGUST 23, 2016 TV PROGRAMS 07:40 Jungle Cubs 07:00 Chopped 08:05 Sofia The First 08:00 Barefoot Contessa: Back To 08:30 Miles From Tomorrow Basics 08:40 PJ Masks 09:00 The Kitchen 09:10 Doc McStuffins 10:00 The Pioneer Woman 03:25 Mad Dogs 09:55 Minnie’s Bow-Toons 11:00 Chopped 03:00 Extreme Engineering 04:10 Casualty 10:00 Sofia The First 12:00 Guy’s Big Bite 03:48 Smash Lab 05:05 The Musketeers 11:00 The Lion Guard 13:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 04:36 Meteorite Men 06:00 Casualty 11:30 Jake And The Never Land 14:00 Man Fire Food 05:24 How The Universe Works 06:55 Casualty Pirates 15:00 Chopped 06:12 How Do They Do It? 07:50 Death In Paradise 12:30 Gummi Bears 16:00 The Kitchen 06:36 Food Factory 08:45 Call The Midwife 13:00 Sofia The First 17:00 The Pioneer Woman 07:00 How Do They Do It? 09:40 The Musketeers 13:30 Doc McStuffins 18:00 Chopped 07:26 Smash Lab 10:35 Casualty 14:00 The Lion Guard 19:00 Guy’s Grocery Games 08:14 How The Universe Works 11:30 Death In Paradise 14:30 Aladdin 20:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 09:02 Extreme Engineering 12:25 Call The Midwife 14:55 Jake And The Never Land 21:00 Man v Food 09:50 How Do They Do It? 13:20 The Musketeers Pirates 22:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 10:14 Food Factory 14:15 Casualty 15:05 Goldie & Bear 23:00 Iron Chef America 10:38 Meteorite Men 15:10 Death In Paradise 15:30 Miles From Tomorrow 00:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 11:26 Smash Lab 16:05 Call The Midwife 16:00 Doc McStuffins 01:00 Man v Food 12:14 How The Universe Works 17:00 The Musketeers 16:55 Sofia The First -

Sunday Morning Grid 7/2/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

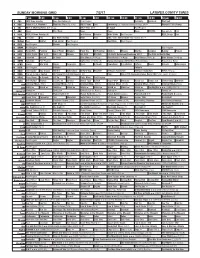

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/2/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Hot Seat PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Swimming U.S. National Championships. (N) Å Women’s PGA Champ. 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News XTERRA Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid 2017 U.S. Senior Open Final Round. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 The Path to Wealth-May 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) Duro pero seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. Recuerda y Gana 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow NOVA (TVG) Å 52 KVEA Hoy en la Copa Confed Un Nuevo Día Edición Especial (N) Copa Copa FIFA Confederaciones Rusia 2017 Chile contra Alemania. -

2018 Women's Luncheon Sponsor Packet

COLORADO 2018 WOMEN’S LUNCHEON OCTOBER 26, 2018 SEAWELL BALLROOM • 1350 ARAPAHOE ST, DENVER with special guest GIULIANA RANCIC PRESENTED BY For sponsorship information contact Brittani Johnson [email protected] 2018 WOMEN’S LUNCHEON HOST COMMITTEE Karmen Berentsen Audrey Kinsman Alyson Owens Sandy Harvath Mari Ann Martin Melanie Schmeiding Stacey Hekkert Gretchen McLaughlin Carolyn Shames *HOST COMMITTEE STILL IN FORMATION We invite you to serve as a member of the 2018 Women’s Luncheon Host Committee. As a host committee member, your efforts are vital to the success of the event. Host Committee members contribute to the event in the following ways: • Commit to sponsoring a table at the Silver level ($5,000) or higher and filling the table of 10 people. • Promote the event and mission of ACE Scholarships to your social circles. • Support the Power of the Purse raffle by supplying quality purses or making introductions to help secure donated items. Host Committee members will receive the following benefits: • Listing in the event collateral • One complimentary raffle ticket for each of your table guests To become a member of the Women’s Luncheon Host Committee, please contact Brittani Johnson at [email protected]. 2018 WOMEN’S LUNCHEON GIULIANA RANCIC New York Times best-selling author and the winner of the Fan Favorite award at the 2014 Daytime Emmy Awards, Giuliana Rancic is an entertainment journalist, author, fashion and beauty expert and television personality with over 3.5 million devoted followers on Twitter and 10 million followers across her social media platforms. She has been on the red carpet for every mega- event in the entertainment industry (Oscars, Grammy Awards, Golden Globes) interviewing the stars and getting breaking Hollywood scoop as well as all things pop culture. -

Pizzas $ 99 5Each (Additional Toppings $1.40 Each)

Your Secret To A Beautiful Lawn AJW Landscaping Call Me! 910-271-3777 June 2 - 8, 2018 Mowing | Edging | Pruning | Mulching FREE Estimates | Licensed | Insured | Local References MANAGEr’s SPECIAL Family feud 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Pizzas $ 99 5EACH (Additional toppings $1.40 each) Brian Cox stars in “Succession” 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, June 2, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Father knows best: An aging patriarch fights for his company in HBO’s ‘Succession’ By Kyla Brewer includes Will Ferrell (“Saturday comedy website Funny or Die in TV Media Night Live”), Adam McKay (“The 2007, along with Michael Kvamme Big Short,” 2015) and Frank Rich and Chris Henchy. However, McKay ealthy families make for ex- (“Veep”). McKay, who directed the has had success with his dramatic Wcellent prime-time viewing, pilot, explained the focus of the se- work as well, winning an Oscar for especially dysfunctional ones. ries in an HBO news release. his work on the film “The Big Leave it to HBO to elevate the en- “There’s no question that ‘Suc- Short” (2015). semble family drama to new cession,’ at its root, is a family sto- Of course, TV fans have come to heights as the cable giant takes a ry,” McKay noted. “There’s also a expect comedy from funnyman Fer- look at a family battling for control tragic side to it, where you see how rell, but “Succession” isn’t his first of a media empire in a new high- massive wealth and power distorts foray into more dramatic territory. -

Kristen Connolly Helps Move 'Zoo' Far Ahead

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! June 23 - 29, 2017 waxahachietx.com U J A M J W C Q U W E V V A H 2 x 3" ad N A B W E A U R E U N I T E D Your Key E P R I D I C Z J Z A Z X C O To Buying Z J A T V E Z K A J O D W O K W K H Z P E S I S P I J A N X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad A C A U K U D T Y O W U P N Y W P M R L W O O R P N A K O J F O U Q J A S P J U C L U L A Co-star Kristen Connolly L B L A E D D O Z L C W P L T returns as the third L Y C K I O J A W A H T O Y I season of “Zoo” starts J A S R K T R B R T E P I Z O Thursday on CBS. O N B M I T C H P I G Y N O W A Y P W L A M J M O E S T P N H A N O Z I E A H N W L Y U J I Z U P U Y J K Z T L J A N E “Zoo” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Jackson (Oz) (James) Wolk Hybrids Place your classified Solution on page 13 Jamie (Campbell) (Kristen) Connolly (Human) Population ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Mitch (Morgan) (Billy) Burke Reunited Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Abraham (Kenyatta) (Nonso) Anozie Destruction Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Dariela (Marzan) (Alyssa) Diaz (Tipping) Point Kristen Connolly helps Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it move ‘Zoo’ far ahead 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light Cardinals. -

The Silence Surrounding Surrogacy: a Call for Reform in Alabama

5 MILLER 1375-1391 (DO NOT DELETE) 7/23/2014 10:31 AM THE SILENCE SURROUNDING SURROGACY: A CALL FOR REFORM IN ALABAMA I. METHODS OF SURROGACY AND ITS PLACE IN THE UNITED STATES AND ALABAMA ............................................................................. 1376 II. LEGAL TREATMENT OF SURROGACY AGREEMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES .......................................................................................... 1379 A. The First Landmark Case: In re Baby M .............................. 1379 B. California’s Response: Johnson v. Calvert ........................... 1382 III. REGULATION OF SURROGACY ............................................................ 1383 A. Federal Legislation ............................................................... 1383 B. The Model Acts ...................................................................... 1385 1. Uniform Parentage Act .................................................... 1385 2. ABA Model Act Governing Assisted Reproductive Technologies .................................................................... 1386 C. State Legislation .................................................................... 1386 IV. LEGAL TREATMENT OF SURROGACY AGREEMENTS IN ALABAMA ... 1388 A. Call for Legislative Action ..................................................... 1388 B. Legislative Recommendation for Alabama ............................ 1389 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 1391 Surrogacy is the “use of [a] woman’s gestational