Dutch Golden Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIMON DE VOS (1603 – Antwerp – 1676)

CS0371 SIMON DE VOS (1603 – Antwerp – 1676) The Lamentation Signed and dated, lower left: S. D Vos. in et F 1644 Oil on panel, 14½ x 17⅝ ins. (36.8 x 44.8 cm) PROVENANCE With James A. Gorry, Dublin, until Anonymous sale, Christie’s, London, 6 October, 1950, lot 123 Anonymous sale, Christie’s, London, 9 July 2014, lot 159 (The Property of a Lady) Private collection, England, until 2021 Born in Antwerp in 1603, Simon de Vos studied with the portraitist Cornelis de Vos (1603- 1676) before enrolling as a master in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke in 1620. Subsequently, he is thought to have rounded off his education with a trip to Italy. Although undocumented, a sojourn in Italy during the 1620s is the only plausible explanation for the stylistic similarities that exist between some of his early genre scenes and those of the German-born artist Johann Liss (c. 1595-1631), who was in Rome and Venice at that time. In any event, de Vos was back in his hometown by 1627, the year in which he married Catharina, sister of the still-life painter Adriaen van Utrecht (1599-1652). He remained in Antwerp for the rest of his life. In his early career, Simon de Vos painted mostly cabinet-sized genre scenes. He specialised in merry company subjects, whose style and composition recall similar works by such Dutch contemporaries as Antonie Palamedesz. (1601-1673), Dirck Hals (1591-1656) and Pieter Codde (1599-1678). After about 1640, he turned increasingly to biblical subjects that show the influence of Frans Francken the Younger (1581-1642), Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). -

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 • Fourth Sunday After Pentecost

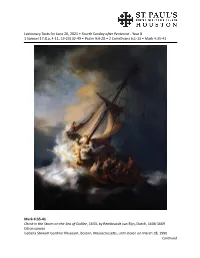

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 •Fourth Sunday after Pentecost- Year B 1 Samuel 17:(1a, 4-11, 19-23) 32-49 • Psalm 9:9-20 • 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 • Mark 4:35-41 Mark 4:35-41 Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633, by Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669 Oil on canvas Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, until stolen on March 18, 1990 Continued Lectionary Texts for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost• June 20, 2021 • Page 2 In his only painted seascape, Rembrandt dramatically portrays the continuing battle of nature against human frailty, both physical and spiritual. The frightened and overwhelmed disciples struggle to retain control of their fishing boat as huge waves crash over the bow. One disciple is hanging over the side of the boat vomiting. A sail is torn, rope lines are flying loose, disaster is imminent as rocks appear in the left foreground. The dark clouds, the wind, the waves combine to create the terror of the painting and the terror of the disciples. Nature’s upheaval is the cause of, as well as a metaphor for, the fear that grips the disciples. The emotional turbulence is magni- fied by the dramatic impact of the painting, approximately 4’ wide by 5’ high. Jesus, whose face is lightened in the group on the right, remains calm. He woke up and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Peace! Be still!” Then the wind ceased, and there was a dead calm, and he asked the disciples, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” The face of a 13th disciple looks directly out at the viewer in the horizontal center of the painting. -

Verbal Pentimento in Donna Tartt’S the Goldfinch

Vilnius University Faculty of Philology Department of English Philology Marija Petravičiūtė The Art of Mourning: Verbal Pentimento in Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of MA in English Studies Academic advisor: dr. Rūta Šlapkauskaitė 2017 Contents: Abstract ................................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 4 2. The Matter of Matter: A Theoretical Frame ................................................. 11 3. The Denial of Death: Art and the Illusion of Presence ................................. 20 4. Conclusions ................................................................................................... 36 Summary in Lithuanian ....................................................................................... 37 References ........................................................................................................... 38 Appendix ............................................................................................................. 40 2 Abstract The present MA paper aims to examine Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (2013), a novel which is primarily preoccupied with the themes of art and death. Seeing as one of the purposes of this thesis is to establish relevant connections between the logic of still life paintings, the protagonist’s life choices and, consequently, his -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Visual Culture

Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture By © 2017 Megan C. Blocksom Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Dr. Marni Kessler Dr. Anne D. Hedeman Dr. Stephen Goddard Dr. Diane Fourny Date Defended: November 17, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Megan C. Blocksom certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract This study examines representations of religious and secular processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands. Scholars have long regarded representations of early modern processions as valuable sources of knowledge about the rich traditions of European festival culture and urban ceremony. While the literature on this topic is immense, images of processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands have received comparatively limited scholarly analysis. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature has to do with the prevailing perception that Dutch processions, particularly those of a religious nature, ceased to be meaningful following the adoption of Calvinism and the rise of secular authorities. This dissertation seeks to revise this misconception through a series of case studies that collectively represent the diverse and varied roles performed by processional images and the broad range of contexts in which they appeared. Chapter 1 examines Adriaen van Nieulandt’s large-scale painting of a leper procession, which initially had limited viewership in a board room of the Amsterdam Leprozenhuis, but ultimately reached a wide audience through the international dissemination of reproductions in multiple histories of the city. -

Taking Dutch Art Seriously: Now and Next? Author(S): MARIËT WESTERMANN Source: Studies in the History of Art, Vol

National Gallery of Art Taking Dutch Art Seriously: Now and Next? Author(s): MARIËT WESTERMANN Source: Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 74, Symposium Papers LI: Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century (2009), pp. 258-270 Published by: National Gallery of Art Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42622727 Accessed: 11-04-2020 11:41 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42622727?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms National Gallery of Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studies in the History of Art This content downloaded from 85.72.204.160 on Sat, 11 Apr 2020 11:41:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms /';-=09 )(8* =-0/'] This content downloaded from 85.72.204.160 on Sat, 11 Apr 2020 11:41:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms MARIËT WESTERMANN New York University Taking Dutch Art Seriously : Now and Nextl vative, staid, respectable discipline, some- posium with mounting anxiety. -

Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier

2 Go Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier Discussion Questions 1. Do you think Griet was typical of other girls her age? In what ways? How did she differ? Did you find her compassionate or selfish? Giving or judgmental? 2. In many ways, the primary relationship in this novel appears to be between Griet and Vermeer. Do you think this is true? How do you feel about Vermeer's relationship with his wife? How does that come into play? 3. Peering into 17th century Delft shows a small, self-sufficient city. Where do you think the many-pointed star at the city's center pointed toward? What was happening elsewhere at that time? 4. Discuss the ways religion affected Griet's relationship with Vermeer. His wife? Maria Thins? Mount Laurel Library 100 Walt Whitman Ave., Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 856-234-7319 www.mtlaurel.lib.nj.us Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier Discussion Questions continued 5. Maria Thins obviously understood Vermeer's art more than his wife did. Why do you think this was the case? Do you think she shared Griet's talents? 6. Do you think Griet made the right choice when she married the butcher's son? Did she have other options? 7. How is Delft different to or similar to your town or city? Are the social structures comparable? 8. Though Girl with a Pearl Earring appears to be about one man and woman, there are several relationships at work. Which is the most difficult relationship? Which is the most promising? Questions taken permission from ReadingGroupGuides.com. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

DUTCH and ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850

DUTCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850 The art and ship models in this station are devoted to the early Dutch and English seascape painters. The historical emphasis here explains the importance of the sea to these nations. Historical Overview: The Dutch: During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as one of the great maritime oriented empires. The Dutch Republic was born in 1579 with the signing of the Union of Utrecht by the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Two years later the United Provinces of the Netherlands declared their independence from the Spain. They formed a loose confederation as a representative body that met in The Hague where they decided on issues of taxation and defense. During their heyday, the Dutch enjoyed a worldwide empire, dominated international trade and built the strongest economy in Europe on the foundation of a powerful merchant class and a republican form of government. The Dutch economy was based on a mutually supportive industry of agriculture, fishing and international cargo trading. At their command was a huge navy and merchant fleet of fluyts, cargo ships specially designed to sail through the world, which controlled a large percentage of the international trade. In 1595 the first Dutch ships sailed for the East Indies. The Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC as it was known) was established in 1602 and competed directly with Spain and Portugal for the spices of the Far East and the Indian subcontinent. The success of the VOC encouraged the Dutch to expand to the Americas where they established colonies in Brazil, Curacao and the Virgin Islands. -

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam)

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Gabriel Metsu” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/gabriel- metsu/ (accessed September 28, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Gabriel Metsu Page 2 of 5 Gabriel Metsu was born sometime in late 1629. His parents were the painter Jacques Metsu (ca. 1588–1629) and the midwife Jacquemijn Garniers (ca. 1590–1651).[1] Before settling in Leiden around 1615, Metsu’s father spent some time in Gouda, earning his living as a painter of patterns for tapestry manufacturers. No work by Jacques is known, nor do paintings attributed to him appear in Leiden inventories.[2] Both of Metsu’s parents came from Southwest Flanders, but when they were still children their families moved to the Dutch Republic. When the couple wed in Leiden in 1625, neither was young and both had previously been married. Jacquemijn’s second husband, Guilliam Fermout (d. ca. 1624) from Dordrecht, had also been a painter. Jacques Metsu never knew his son, for he died eight months before Metsu was born.[3] In 1636 his widow took a fourth husband, Cornelis Bontecraey (d. 1649), an inland water skipper with sufficient means to provide well for Metsu, as well as for his half-brother and two half-sisters—all three from Jacquemijn’s first marriage. -

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and Background Information 1. Raffaello Santi Born in Urbino, Then a Small but Important C

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and background information 1. Raffaello Santi born in Urbino, then a small but important cultural center of the Italian Renaissance; trained by his father, Giovanni Santi. 2. Influenced by Perugino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo; worked in Florence 1504-08, in Rome 1508-20, where his chief patrons were Popes Julius II and Leo X. 3. Pictorial structures and concepts: the picture plane, linear and atmospheric perspective, foreshortening, chiaroscuro, contrapposto. 4. Painting media a. Tempera (egg binder and pigment) or oil (usually linseed oil as binder); support: wood panel (prepared with gesso ground) or canvas. b. Fresco (painting on wet plaster); cartoon, pouncing, giornata. Selected works 5. Religious subjects a. Marriage of the Virgin (“Spozalizio”), 1504 (oil on roundheaded panel, 5’7” x 3’10”, Pinacoteca de Brera, Milan) b. Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1505 (oil on panel, 44.5” x 34.6”, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) c. Madonna del Cardellino (“Madonna of the Goldfinch”), 1506 (oil on panel, 3’5” x 2’5”, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) d. Virgin and Child with St. Sixtus and St. Barbara (“Sistine Madonna”), 1512-13 (oil on canvas, 8’8” x 6’5”, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden) 6. Portraits a. Agnolo Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) b. Maddalena Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) c. Cardinal Tommaso Inghirami, c. 1510-14 (oil on panel, 2’11 ¼” x 2’, Pitti Palace, Florence) d. Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1514-15 (oil on canvas, 2’8” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) e.