Lutheran Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Lita Ford and Doro Interviewed Inside Explores the Brightest Void and the Shadow Self

COMES WITH 78 FREE SONGS AND BONUS INTERVIEWS! Issue 75 £5.99 SUMMER Jul-Sep 2016 9 771754 958015 75> EXPLORES THE BRIGHTEST VOID AND THE SHADOW SELF LITA FORD AND DORO INTERVIEWED INSIDE Plus: Blues Pills, Scorpion Child, Witness PAUL GILBERT F DARE F FROST* F JOE LYNN TURNER THE MUSIC IS OUT THERE... FIREWORKS MAGAZINE PRESENTS 78 FREE SONGS WITH ISSUE #75! GROUP ONE: MELODIC HARD 22. Maessorr Structorr - Lonely Mariner 42. Axon-Neuron - Erasure 61. Zark - Lord Rat ROCK/AOR From the album: Rise At Fall From the album: Metamorphosis From the album: Tales of the Expected www.maessorrstructorr.com www.axonneuron.com www.facebook.com/zarkbanduk 1. Lotta Lené - Souls From the single: Souls 23. 21st Century Fugitives - Losing Time 43. Dimh Project - Wolves In The 62. Dejanira - Birth of the www.lottalene.com From the album: Losing Time Streets Unconquerable Sun www.facebook. From the album: Victim & Maker From the album: Behind The Scenes 2. Tarja - No Bitter End com/21stCenturyFugitives www.facebook.com/dimhproject www.dejanira.org From the album: The Brightest Void www.tarjaturunen.com 24. Darkness Light - Long Ago 44. Mercutio - Shed Your Skin 63. Sfyrokalymnon - Son of Sin From the album: Living With The Danger From the album: Back To Nowhere From the album: The Sign Of Concrete 3. Grandhour - All In Or Nothing http://darknesslight.de Mercutio.me Creation From the album: Bombs & Bullets www.sfyrokalymnon.com www.grandhourband.com GROUP TWO: 70s RETRO ROCK/ 45. Medusa - Queima PSYCHEDELIC/BLUES/SOUTHERN From the album: Monstrologia (Lado A) 64. Chaosmic - Forever Feast 4. -

Auditing the Echonest – Investigations to Gauge Output Accuracy Submission for Auditing Algorithms from the Outside at ICWSM-15

Auditing The Echonest – Investigations to gauge output accuracy Submission for Auditing Algorithms From the Outside at ICWSM-15 Justin Gagen Transforming Musicology Goldsmiths, University of London [email protected] March 11th 2015 The Echonest is a collection of algorithms that uses the Internet as its data source and attempts to generate `music intelligence' from this. How does one audit a large system that utilises petabytes of data to synthesize knowledge in a dynamic way? How are deeply embedded, fuzzy concepts, such as `cultural vectors', auditable at all? I propose that audit-by-use-case is the only viable method for systems of this nature and complexity, and visualisation of data output can assist in this endeavour and render it as a task on a human- scale. 1) The System The Echonest, a `music intelligence' company formed in 2005 by two MIT doctoral graduates (Brian Whitman and Tristan Jehan) and acquired in 2014 by Spotify, the streaming-music provider, uses a blended approach to music data gathering and `intelligence' generation. Audio analysis features and metadata gathered from multiple data sources across the Internet (including web pages, and structured, user-edited sources, such as WikiPedia, Discogs, and MusicBrainz) are combined and synthesized into musical `knowledge'. This is then used by other companies, including Spotify, to generate playlists, recommendations and `radio' stations for listeners. Whitman (2012), in a blog post entitled `How music recommendation works - and doesn't work', describes how `real people feeding information into a large automated system from all different sources' is the approach taken by Echonest to gather information written around music. -

The Influence of Role Models in Metal Musicians' Composing and Career

Niina Lämsä The influence of role models in metal musicians’ composing and career How do the songs come alive? Thesis CENTRIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Music pedagogy June 2017 ABSTRACT Centria University Date Author of Applied Sciences June 2017 Niina Lämsä Degree programme Music pedagogy Name of thesis The influence of role models in metal musicians’ composing and career Instructor Pages Kirsti Rasehorn 20 The idea of this thesis was to study the influence of role models in metal musicians’ composing and career. The information was collected from theme interviews from the members of Amaranthe, Epica and Sonata Arctica and this thesis was written based on their answers using qualitative research. Based on the interviews we can say that each musician has taken some influences from their role models. The influences they take from other musicians’ songs are mostly the stylish or atmospherical influence. For all musicians, the common source of inspiration was books and movies. The role models affected these people in different ways, but what was common was that they have learned from them with consideration, following only the good practices. In this thesis I compared my own composing process to my role models’ composing processes. There was a lot in common, it turned out, that the most of these composers compose alone. The most important tips for aspiring composers were to “follow your heart”, “let the music choose you” and “never give up”. Key words Composing, metal music, music, role models TIIVISTELMÄ OPINNÄYTETYÖSTÄ Centria- Aika Tekijä/tekijät ammattikorkeakoulu Kesäkuu 2017 Niina Lämsä Koulutusohjelma Musiikin koulutusohjelma Työn nimi Esikuvien vaikutus metallimuusikoiden säveltämiseen ja uraan Työn ohjaaja Sivumäärä Kirsti Rasehorn 20 Opinnäytetyön tarkoitus oli tutkia esikuvien vaikutusta metallimuusikoiden sävellysprosessiin ja uraan. -

Formed in Göteborg, Sweden, in 1993 by Guitarist Oscar Dronjak. Early

Formed in Göteborg, Sweden, in 1993 by guitarist Oscar Dronjak. Early line-ups included members from In Flames and Dark Tranquillity, most notably Jesper Strömblad, who continued to write songs together with Oscar and singer Joacim Cans despite leaving before the first album was released. Glory To The Brave (1997) and Legacy Of Kings (1998) cemented the band as the pioneers of modern Eighties heavy metal. Often credited with bringing back the melodies and honesty in music, the world-wide crusade continued with Renegade (2000), an album that generated a breakthrough for HammerFall and metal music in general in the mainstream media in Sweden. The line-up was now complete with drummer Anders Johansson, formerly of Rising Force fame, Stefan Elmgren on guitar and Magnus Rosén on bass guitar. The latter two joined HF before the release of the inaugural record, with Stefan even being a session player on Glory To The Brave. Crimson Thunder (2002) was next, followed by a live album and DVD - One Crimson Night (2003) - recorded in their home town in front of a capacity crowd. The fifth album, aptly titled Chapter V: Unbent, Unbowed, Unbroken (2005) further planted the name HammerFall in the minds of households in Sweden, as well as metal fans all over the world. The band's fourth world tour on as many albums was an even bigger success than before, headlining the U.S. for the first time (after supporting Death and Dio in 1998 and 2002 respectively). Two sportsrelated videos were recorded in 2006, a remake of "Hearts On Fire" for the Swedish Olympic Women's Curling Team, and a brand new song called "The Fire Burns Forever" specifically written for Kajsa Bergqvist, Robert Kronberg and a couple of other Swedish track & field superstars, culminating in a performance at the opening ceremony at the European Athletics Championships in August, bringing HammerFall into the home of 250 million people around the world. -

2 Column Indented

Music By Bonnie 25,000 Karaoke Songs ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years 20 Fingers Actions & Motives 29768 Short Dick Man 1962 Beautiful 29769 Drug Of Choice 29770 3 Doors Down Fix Me 29771 Away From The Sun 6184 Shoot It Out 29772 Be Like That 6185 Through The Iris 20005 Behind Those Eyes 13522 Wasteland 16042 Better Life, The 17627 Citizen Soldier 17628 10,000 Maniacs Duck And Run 6188 Because The Night 1750 Every Time You Go 25704 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Here By Me 17629 Like The Weather 16149 Here Without You 13010 More Than This 16150 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 These Are The Days 1273 Kryptonite 6190 Trouble Me 16151 Landing In London 17631 100 Proof Aged In Soul Let Me Be Myself 25227 Somebody's Been Sleeping In My Bed 27746 Let Me Go 13785 Live For Today 13648 10cc Loser 6192 Donna 20006 Road I'm On, The 6193 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 So I Need You 17632 I'm Mandy 16152 When I'm Gone 13086 I'm Not In Love 2631 When You're Young 25705 Rubber Bullets 20007 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 3 Inches Of Blood Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Deadly Sinners 27748 112 30 Seconds To Mars Come See Me 25019 Closer To The Edge 26358 Dance With Me 22319 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 It's Over Now 22320 Kings And Queens 26359 Peaches & Cream 22321 311 U Already Know 13602 All Mixed Up 16156 12 Stones Don't Tread On Me 13649 We Are One 27248 Down 27749 First Straw 22322 1975, The Love Song 22323 Love Me 29773 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Sound, The 29774 UGH! 29775 36 Crazyfists Bloodwork 29776 2 Chainz Destroy The Map 29777 Spend It 25701 Great Descent, The 29778 2 Live Crew Midnight Swim 29779 Do Wah Diddy 25702 Slit Wrist Theory 29780 Me So Horny 27747 38 Special We Want Some PuXXy 25703 Caught Up In You 1904 2 Pistols (ft. -

Halestorm Announce New Album, ‘The Strange Case Of…’ and Premiere Music

January 24, 2012 Halestorm Announce New Album, ‘The Strange Case Of…’ and Premiere Music Hard rockers Halestorm are announcing the release of their new album, The Strange Case Of…, which will come out April 10. To introduce the disc, the group is releasing the single “Love Bites (So Do I)” to radio today. The track, as well as three other highlights from The Strange Case Of…, is featured on Halestorm’s new EP, Hello, It’s Mz. Hyde, which is available to purchase online today. Produced by Howard Benson (who previously collaborated with the Pennsylvania- band on their self-titled 2009 debut), The Strange Case Of… was named one of Revolver’s “Most Anticipated Albums of the Year.” Halestorm will hit the road hard to support The Strange Case Of…, beginning with a major U.S. trek alongside Godsmack and Staind beginning April 13 at Augusta, Georgia’s John Paul Jones Arena and then continue through mid-May (see the tour dates below). Get your first taste of the EP in the video below, and, below that, check out the track listing for The Strange Case Of… and the group’s tour dates. January 9, 2012 July 22, 2011 In the Studio With Halestorm -- Exclusive Interview Comprised of siblings Lzzy and Arejay Hale, Joe Hottinger and Josh Smith, Halestorm have performed upwards 250 shows a year since their formation in 2006. The group's 2009 self-titled debut album found success on the back of its fine blend of melodic hooks and killer guitar riffs. Halestorm is back in the studio and Noisecreep got an exclusive chance to visit with the band, in the studio, to get all the details on the new record. -

Die Us-Rocker Papa Roach Im Sommer Live in Deutschland Headline-Show in Saarbrücken Und Festival-Auftritte Bestätigt Tickets Ab 16

PRESSEMELDUNG DIE US-ROCKER PAPA ROACH IM SOMMER LIVE IN DEUTSCHLAND HEADLINE-SHOW IN SAARBRÜCKEN UND FESTIVAL-AUFTRITTE BESTÄTIGT TICKETS AB 16. MAI IM VORVERKAUF Die Grammy-nominierte und mehrfach mit Platin ausgezeichnete Alternative Rock-Band Papa Roach kommt im August wieder zurück nach Deutschland. Neben Festivalauftritten beim Dithmarscher Rockfestival und Serengeti Festival werden die Kalifornier am 26. August 2014 in der Garage in Saarbrücken ihre einzige Headline- Show spielen. Tickets für das Konzert in Saarbrücken gibt es ab dem 16. Mai an den bekannten Vorverkaufsstellen, unter der bundesweiten Tickethotline 01806 / 999 000 555 (0,20 EUR/Verbindung aus dt. Festnetz / max. 0,60 EUR/Verbindung aus dt. Mobilfunknetz) oder im Internet unter www.ticketmaster.de. Papa Roach veröffentlichten mit The Connection ihr bisher sechstes Studioalbum. Das 2012 erschienene Werk ist bereits die zweite Veröffentlichung auf ihrem eigenen Label Eleven Seven Music. Es wurde von Rockveteran James Michael (Sixx:A.M., Halestorm) und Goldfinger-Frontmann John Feldmann (Panic At The Disco, The Used, Escape The Fate) produziert und von der Kritik überschwänglich gelobt. Mit der europäischen Sonderedition des Albums im Gepäck begeisterten Papa Roach 2013 auf gleich zwei Tourneen: Im Festival-Sommer und im November 2013 konnten sich die Fans davon überzeugen, dass das Quintett auch im 20. Jahr seines Bestehens nichts von ihrer Energie und Brillanz verloren hat. Papa Roach haben weltweit mehr als 10 Millionen Alben verkauft. Die Band wurde zweimal für den Grammy nominiert und einmal für die MTV VMAs. Darüber hinaus konnte sie elf Top 10 Rock Hits sowie sieben Top 10 Alternative Hits landen. Auch den „Most Played Alternative Song of the Decade“ (BDS) können sie mit ihrer Durchbruch- Single „Last Resort“ für sich beanspruchen. -

Karaoke Songs by ARTIST

Karaoke Songs by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title 10 Years Wasteland Live For Today 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Loser Like The Weather Road I'm On More Than This Train These Are The Days When I'm Gone Trouble Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings & Queens 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping Up In The Air 10CC Donna 311 All Mixed Up Dreadlock Holiday Amber I'm Mandy Beyond The Grey Sky I'm Not In Love Creatures (For A While) Rubber Bullets Don't Tread On Me Things We Do For Love First Straw Wall Street Shuffle Love Song 112 Cupid You Wouldn't Believe 38 Special Back Where You Belong Peaches & Cream Right Here For You Caught Up In You U Already Know Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet Second Chance Teacher, Teacher 112 & Super Cat Na Na Na 3LW I Do 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Co. Playas Gon' Play 1975 City 3oh!3 Don't Trust Me Robbers Double Vision 1979 Chocoloate 3oh!3 & Katy Perry Starstrukk 2 Chainz Spend It 3rd Strike, A No Light 2 Evisa Oh La La La Redemption 2 Live Crew Doo Wah Diddy 3SL Take It Easy Me So Horny 3T Anything We Want Some P***Y! 3T & Michael Jackson Why 2 Pac Changes 4 Non Blondes What's Up How Do You Want It What's Up (Acoustic) 2 Unlimited No Limits 4 Runner Cain's Blood 20 Fingers Lick It 411 Dumb Short D**K Man On My Knees Ride 21 Pilots Teardrops 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 42nd St. -

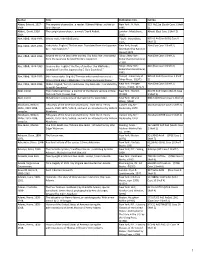

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

ASCAP/BMI Comment

Stuart Rosen Senior Vice President General Counsel November 20, 2015 Chief, Litigation III Section Antitrust Division U.S. Department of Justice 450 5th Street NW, Suite 4000 Washington, DC 20001 Re: Justice Department Review of the BMI and ASCAP Consent Decrees To the Chief of the Litigation III Section: BMI recently alerted its community of affiliated songwriters, composers and publishers to the profound impact 100% licensing would have on their careers, both creatively and financially, if it were to be mandated by the U.S. Department of Justice. In a call to action, BMI provided a letter, one for songwriters and one for publishers, to which their signatures could be added. The response was overwhelming. BMI received nearly 13,000 signatures from writers, composers and publishers of all genres of music, at all levels in their careers. Some of the industry's most well- known songwriters added their names, including Stephen Stills, Cynthia Weil, Steve Cropper, Ester Dean, Dean Pitchford, Congressman John Hall, Trini Lopez, John Cafferty, Gunnar Nelson, Lori McKenna, Shannon Rubicam and Don Brewer, among many others. Enclosed you will find the letters, with signatures attached. On behalf of BMI, I strongly urge you to consider the voices of thousands of songwriters and copyright owners reflected here before making a decision that will adversely affect both the creators, and the ongoing creation of, one ofAmerica's most important cultural and economic resources. Vert truly yours, Stuart Rosen 7 World Trade Center, 250 Greenwich Street, New York, NY 10007-0030 (212) 220-3153 Fax: (212) 220-4482 E-Mail: [email protected] ® A Registered Trademark of Broadcast Music, Inc. -

SAINTS of LOS ANGELES As Recorded by Motley Crue (From the 2008 Album "Saints of Los Angeles")

SAINTS OF LOS ANGELES As recorded by Motley Crue (from the 2008 Album "Saints of Los Angeles") Transcribed by tonedeafidiot Music by Nikki Sixx, James Michael, Dj Ashba, and Marti Frederikson A5A5 BB5 5 xo xx x ` ` xx A Intro 8 1 4 I 4 Gtrs I, II T A B 9 I V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V gV V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. ||| T 2 0 2 0 2 0 2 0 0 2 2 0 2 0 2 0 2 0 3 A 2 0 2 0 2 0 2 0 0 2 2 0 2 0 2 0 2 0 3 B 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 P P P P P P P P Printed using TabView by Simone Tellini - http://www.tellini.org/mac/tabview/ SAINTS OF LOS ANGELES - Motley Crue Page 2 of 15 11 I V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V VgV V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V VgV V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. |||| P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M.