Wildlife Relations: a Case of Gir Protected Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EQUITY DIVIDEND for the YEAR 2012-2013 Details of Unclaimed Dividend Amount As on Date of Annual General Meeting (AGM Date - 4Th August, 2018) SI

WOCKHARDT LIMITED - EQUITY DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2012-2013 Details of unclaimed dividend amount as on date of Annual General Meeting (AGM Date - 4th August, 2018) SI. Name of Shareholders Address State Pin code Folio No. / DP ID Dividend Proposed Date no. Client ID No. Amount of Transfer to unclaimed IEPF in ( Rs.) 1 A D RAMYA 6/25 SUN SANDS APTS 4TH SEAWAR D TIRUVANMIYUR Tamil Nadu 600041 1207650000003316 50.00 07-Oct-2020 CHENNAI 2 A K GARG C/O M/S ANAND SWAROOP FATEHGANJ [MANDI] Uttar Pradesh 203001 W0000966 1500.00 07-Oct-2020 BULUNDSHAHAR 3 A M LAZAR ALAMIPALLY KANHANGAD Kerala 671315 W0029284 3000.00 07-Oct-2020 4 A M NARASIMMABHARATHI NO 140/3 BAZAAR STREET AMMIYARKUPPAM PALLIPET-TK Tamil Nadu 631301 1203320004114751 125.00 07-Oct-2020 THIRUVALLUR DT THIRUVALLUR 5 A MALLIKARJUNA RAO DOOR NO 1/1814 Y M PALLI KADAPA Andhra Pradesh 516004 IN30232410966260 250.00 07-Oct-2020 6 A RAJASEKHAR REDDY MIG NO 29 APHB COLONY KORRAPADU ROAD KADAPA DIST Andhra Pradesh 516360 1204470003205849 10.00 07-Oct-2020 PRODDATUR 7 A SATHISH KUMAR W 6, NORTH MAIN ROAD, ANNANAGAR WEST, CHENNAI Tamil Nadu 600101 1203500000082702 25.00 07-Oct-2020 8 A SELVAKUMARI W/O R AMARNATH 52 APPU ST SALEM Tamil Nadu 636002 W0033114 1000.00 07-Oct-2020 9 A SUNILA B 301 GULMOHAR CHS SECTOR 42 NERUL WEST NAVI Maharashtra 400070 IN30021411886342 50.00 07-Oct-2020 MUMBAI 10 A T MRANGARAMANUJAM ADVOCATE 3-6-369/A/10 STREET NO 1 HIMAYATNAGAR Andhra Pradesh 500029 W0013258 2000.00 07-Oct-2020 HYDERABAD 11 AARADHANA GUPTA H NO -1968, INDIRA NAGAR, ORAI Uttar Pradesh 285001 1205460000168915 -

Mendarda, Junagarh District, Gujarat

Draft Report क� द्र�यभू�म �ल बो जल संसाधन, नद� �वकास और गंगा संर�ण मंत्रा भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Mendarda, Junagarh District, Gujarat पि�चमी म鵍ा �ेत, अहमदाबाद West Central Region, Ahmedabad भारत सरकार जल संसाधन, नदी िवकास एवम् गंगा संरक् मं�ालय क��ीय भूिम जल बोडर GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPS & MANAGEMENT PLANS MENDARDA, JUNAGADH DISTRICT, GUJARAT STATE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPS & MANAGEMENT PLANS MENDARDA TALUKA, JUNAGADH DISTRICT, GUJARAT STATE 1. SALIENT FEATURES 1 Name of the Mendarda - 363.86 Km2 TALUKA& Area, 21°10’29” to 21°25’15” N Location(Fig-1) 70°20’48” to 70°34’27” E 2 No. of Town, villages 0, 66 3 District/State Junagadh/Gujarat 4 Population (2011 Male- 35440, Female- 33091, Total- 68,531 Census) 5 Normal Rainfall (mm) 858.78 mm- Monsoon Rainfall (IMD) (in mm) (Long Term) 50 969.60 mm -Average Monsoon Rainfall (in mm) (2003-12) 6 Agriculture (20015-16) Kharif Crops Rabi Crops Crop Area in Hact Crop Area in Hact Groundnut 22100 Wheat 500 Tal 0 Juvar 0 Castor 0 Castor 0 Gram 20 Bajri 0 Bajri 15 Tuver 45 Tuver 0 Mug 65 Mug 80 Udad 130 Mustered 0 Cotton 300 Isabgol 10 Sugarcane 0 Sugarcane 0 Vegetables 70 Vegetables 40 Fodder 750 Fodder 150 Gam Guvar 0 Jira 10 Soyabin 40 Onion 40 Coriander 3900 Garlic 30 Methi 10 Total 23500 Total 4805 7 Existing and future Sector Existing (MCM) Future water demands (MCM) (MCM) (Year 2025) Domestic and Industrial 1.99 2.68 Irrigation 52.43 31.38 8 Water level behaviour 12.98-17.00 m (Pre-monsoon) (2015)(Fig-2 & 3) AQUIFER MAPS & MANAGEMENT PLANS MENDARDA TALUKA, JUNAGADHDISTRICT, GUJARAT STATE 205 Fig-1: Location Map 1. -

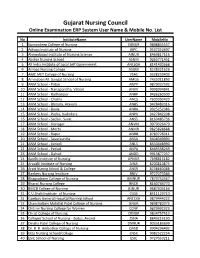

Gujarat Nursing Council Online Examination ERP System User Name & Mobile No

Gujarat Nursing Council Online Examination ERP System User Name & Mobile No. List No InstituteName UserName MobileNo 1 Sumandeep College of Nursing SUNUR 9898855557 2 Adivasi Institute of Nursing AIPC 9537352497 3 Ahmedabad Institute of Nursing Science AINUR 8469817116 4 Akshar Nursing School ASNM 9265771451 5 All India Institute of Local Self Government ANLSGA 8141430568 6 Ambaji Nursing College ASGM 8238321626 7 AMC MET College of Nursing VSAS 9328259403 8 Aminaben M. Gangat School of Nursing AMGS 7435011893 9 ANM School - Patan ANPP 9879037592 10 ANM School - Nanapondha, Valsad ANVV 9998994841 11 ANM School - Radhanpur ANRP 9426260500 12 ANM School - Chotila ANCS 7600050420 13 ANM School - Bhiloda, Aravalli ANBS 9428482016 14 ANM School - Bavla ANBA 9925252386 15 ANM School - Padra, Vadodara ANPV 9427842208 16 ANM School - Sachin, Surat ANSS 8160485736 17 ANM School - Visnagar ANVM 9979326479 18 ANM School - Morbi ANMR 9825828688 19 ANM School - Rapar ANRB 8780726011 20 ANM School - Savarkundla ANSA 9408349990 21 ANM School - Limbdi ANLS 8530448990 22 ANM School - Petlad ANPA 8469538269 23 ANM School - Dahod ANDD 9913877237 24 Apollo Institute of Nursing APNUR 7698815182 25 Aravalli Institute of Nursing AINA 8200810875 26 Arpit Nuring School & College ANSR 8238660088 27 Bankers Nursing Institute BNIV 9727073584 28 Bhagyalaxmi College of Nursing BMNUR 7874752567 29 Bharat Nursing College BNCR 8160744770 30 BMCB College of Nursing BJNUR 9687404164 31 C.U.Shah Institute of Nursing CUSS 8511123710 32 Cambay General Hospital Nursing School ANTCKA 9879444223 33 Chanchalben Mafatlal Patel College of Nursing GNUR 9898780375 34 Chitrini Nursing College for Women CCNP 9829992323 35 Christ College of Nursing CRNUR 9834757510 36 College/ School of Nursing - Zydus, Anand ZSNA 8849216190 37 Dinsha Patel College of Nursing DNNUR 9033183699 38 Dr. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

In Gujarat Sr. Place Dealer Address 1 Amreli Maruti Tractors Opp. Market

In Gujarat Sr. Place Dealer Address 1 Amreli Maruti Tractors Opp. Market Yard, 84, Hirak Baug, Shopping Centre, Amreli 2 Jamkan-Dorna Patel Tractors Agency Nr. Kanya Chhatralaya, Kalawad Road, Jamkandorna 3 Kalavad Gokul Tractors Nr. Shak Market, Nr. Dhoraji Road, Kalavad (Shitla) 4 Keshod Arjun Tractors Mangrol road, Keshod 5 Bhesan Sardar Agency Sardar Patel shopping cente, Nr. S.T. stand, Bhesan, Dist: Junagadh 6 Sadhali Ganesh Engineering Karjan Road, at Sadhali, Dist: Vadodara. Works 7 Talaja Krishna Tractors Ebhal Dwar, Mahuwa Chowkdi, Mahuwa Rd., Talaja 8 Palitana Shriji Tractors Tran Maliya Building, Nr. Madhuli, Bhavanagar Rd., Palitana, Dist: Bhavnagar 9 Bodeli Shri Sainath Motors Laxmi Shopping Centre, Alipura, Chhota Udaipur Rd., Bodeli-391135, Dist: Vadodara 10 Savli Ashok Auto Mobiles Gokul Vatika shopping centre, Opp. New Bus Station, At: Savli, Dist: Vadodara 11 Godhra Hari Om Tractors Old Jakatnaka, Gondhra Nr. Bus Stop, Kalol Rd., Godhra, Panchmahal 12 Bhavnagar Sagar Tractors 303, Trade Cantor, Nr. Bhabniya Blood Bank, Kala Naka, Bhavnagar 13 Chikhli Gayatri Tractor Sales N.H. No. 8, Gandhi Complex, G Floor, Nr. & Service Kalpana Guest House, Chikhli Char Rasta, Chikhli 14 Dhandhuka Rajshakti Tractors Arpan Building, Opp. Birla high school, S.T. Rd., Dhandhuka, Dist: Ahmedabad 15 Patan Brahmani Tractors & G-102, Sidhpur Char Rasta, Patan Jaldhara Irrigation 16 Padra Ashok Automobiles Opp. S.T. Stand, Padra 17 Porbandar Shiv Shakti Sales Jamnagar high way Nr. SBS bank, Porbandar Agency In Other States Sr. Place Dealer Name Address 1 Banglore Sevac Agro India Pvt. Ltd. 217, Kempe Gowda Layout, Ring road, Laggare, Banglore-58, Karnataka 2 Gobichhe- Snusham Farm Machinery & 232, Sathy Main Rd., Opp. -

PRAGATI SAHAKARI BANK LTD. Unclaimed Deposit Amount Transfer to the Depositer Education and Awareness Fund Scheme 2014 (DEAF – 2015) AS on 31-08-2017

To find your name press ctrl + F and type your name and press enter PRAGATI SAHAKARI BANK LTD. Unclaimed Deposit Amount Transfer to the Depositer Education and Awareness Fund Scheme 2014 (DEAF – 2015) AS on 31-08-2017 P & P PROPERTY P LTD. 203 STERLING CENTER,R C DUTT ROAD,,VADODARA,390001 P D CONSTRUCTION 16.SATKAR SOC.,B/H.GHELANI PETROLPUMP,NIZAMPURA,VADODARA,390005 P D MEHTA 48, VIJAY SOC.,,,VADODARA,390001 P K CHATTERJEE 33, SHREYNAGAR SOC,SUBHANPURA,,VADODARA,390001 P K M ENTERPRISE KALAKUNJ SOCIETY,WATER TANK,KARELIBAUG,VADODARA,VADODARA,390003 P N ENTERPRISE 27/B SITABAUG SOT,MANJALPUR,,VADODARA,390001 P. JOSEPH GERALD MARKETING DIV.,A.C.W LTD,,VADODARA,390003 PABLA RAJINDER SINGH SARUP SINGH 10/10.GUJARAT REFINARY,POWNSHIP JAWAHARNAGAR,,VADODARA,390001 PADMA N KURLEKAR A/1,NIRMAN PARK,VISHWAMITRY RD,MANJALPUR,VADODARA,390001 PADMABEN AMRUTLAL SHAH FA/25, AL. COLONY,,,VADODARA,390001 PADMAKAR BALCHANDRA PATVARDHAN RAMJI MANDIR POLE,KOTHI, RAOPURA,,VADODARA,390001 PADMAKAR BHALCHANDRA PATWARDHAN A/7,MIRA SOC.NEAR HATHIBHAI-,-NBAGAR, DIWALIPURA,,VADODARA,390001 PADMARAI MURALI MISTRY RAJIV NAGAR,SAIYAD VASANA,,VADODARA,390003 PAHLAJ KHANCHAND MALKANI G/3, VIKRAM APPARTMENT,FATEHGANJ,,VADODARA,390001 PALAK PARESHBHAI PATEL BRHAMAN FALIYA,GORWA,,VADODARA,390016 PALAK PINAKIN PATEL 29, ASHOKNAGAR -1,OPP. LIONS HALL, RACE COURSE,,VADODARA,390001 PALAK S JOSHI A/18,SUNMOON PARK SOCIETY,NEAR AKOTA GARDEN,PRODUCTIVITY ROAD,VADODARA,390020 PALAK U PATEL B\54, ALEMBIC COLONY,,,VADODARA,390001 PALASH CONSTRUCTION A\22,LAXMIKUNJ SOCIETY,NEW -

Amreli Index

DISTRICT PROFILE AMRELI INDEX 1 Amreli: A Snapshot 2 Economy and Industry Profile 3 Industrial Locations / Infrastructure 4 Support Infrastructure 5 Social Infrastructure 6 Tourism 7 Investment Opportunities 8 Annexure 2 1 Amreli: A Snapshot 3 Introduction: Amreli § Amreli is located near the Gulf of Khambhat in the Arabian Map1: District Map of Amreli with Talukas Sea, in the western part of Gujarat § The district has 11 talukas, of which the major ones are Amreli, Babra, Bagasara, Jafrabad, Rajula, Savarkundla and Vadiya § Amreli city is the district headquarter of Amreli § Focus industry sectors-Engineering, Port and Ship building, Minerals and Cement PipavavPort: Babra § Pipavav, India’s first private sector port and the world’s third Lathi largest container terminal operating port, is located in Amreli Vadia Amreli Lilia district (Source: Pipavav Port, 2007) Bagasara Savarkundla Minerals: Dhari Khambha Rajula § The district houses large reserves of limestone (Source: District Headquarter Jafrabad Mineral Treasure of Gujarat,, Commissioner of Geology and Mining, Talukas 2002-03) Pipavav City City 4 Fact File 70.30ºto 71.75ºEast (Longitude) Geographical location 20.45ºto 22.25ºNorth (Latitude) Average rainfall 550 mm Rivers Shetrunji, Thebi, Dhatarwadi, Gagdio, Shanti, Vadi and Rayadi Area 7,397 sq.km District headquarter Amreli Talukas 11 Population 1.39 million (As per 2001 Census) Population density 188 persons per sq. km. Sex ratio 987 Females per 1000 Males Literacy rate 66.10% Languages Gujarati, Hindi and English Seismic zone Zone III Source: Socio Economic Review 2006-07 5 2 Economy and Industry Profile 6 Economy and Industry Profile § Amreli is a base for cement, metallurgical, electrical equipments, ports and ship building industries § Due to the presence of large reserves of limestone, several major cement conglomerates, such as Larson & Toubro and Ultra Tech Cement Co. -

4 A.P. SINGH.Cdr

Indian Forester, 143 (10) : 993-1003, 2017 ISSN No. 0019-4816 (Print) http://www.indianforester.co.in ISSN No. 2321-094X (Online) THE ASIATIC LION (PANTHERA LEO PERSICA): 50 YEARS JOURNEY FOR CONSERVATION OF AN ENDANGERED CARNIVORE AND ITS HABITAT IN GIR PROTECTED AREA, GUJARAT, INDIA A.P. SINGH Wildlife Circle, Sardar Baug, Junagadh, Gujarat (India) E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) is a flagship species of the semi-arid dry deciduous forest tracts of Gujarat in Saurashtra. The species was critically endangered and the numbers had drastically reduced from its historic range due to loss of habitat and hunting. A ban on hunting was enforced in the last remnant pocket of their territory, the Gir forests by the erstwhile Nawab of Junagadh. Post-independence, due to the persistent efforts of the State Forest Department with the continuous support of local people, the population has been rescued from the brink of extinction and now the number has reached to 523 in 2015. Because of this the species has been upgraded to Endangered Category of the IUCN. This poses a globally acclaimed conservation success story of a large carnivore. The lion population once confined to about 1800 km2 of Gir forest area now occupies an area of 7000 km2 and is distributed in about 12000 km2 area of Saurashtra region, Greater Gir landscape of Gujarat, thus reclaiming its lost territory. This paper discusses the various measures and actions that were taken to ensure that this unique species could be conserved in its native range and to ensure long term conservation in a dynamic habitat. -

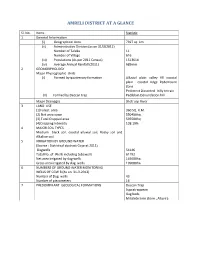

Amreli District at a Glance

AMRELI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. No. Items Statistic 1 General Information (i) Geographical Area 7397 sq. km. (ii) Administrative Division (as on 31/3/2012) Number of Taluka 11 Number of Village 616 (iii) Populations (As per 2011 Census) 1513614 (iv) Average Annual Rainfall (2011) 689mm 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units (i) Formed by quaternary formation Alluvial plain valley fill coastal plain coastal ridge Pedemount Zone Pediment Dissected hilly terrain (II) Formed by Deccan trap Pediblain Denundation hill Major Drainages Shetrunji River 3 LAND USE (1)Forest area 360 SQ. K.M. (2) Net area sown 550400hq. (3) Total Cropped area 595500hq (4)Cropping Intensity 108.19% 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES Medium black soil, coastal alluvial soil, Rocky soil and Alkaline soil. 5 IRRIGATION BY GROUND WATER (Source : Statistical abstract Gujarat 2011) Dugwells 54146 Total No. of Wells including tubewells 61192 Net area irrigated by dug wells 165600ha. Gross area irrigated by dug wells 199000ha. 6 NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGW B (As on 31-3-2012) Number of Dug wells 43 Number of piezometers 16 7 PREDOMIN ANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Deccan Trap Supratrappean Gag beds Milialete lime stone , Alluvira Sl. No. ITEMS Statistic 8 HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water Bearing formation s : Deccan trap, Miliolite, lime stone & Alluvium Depth to water level during 2012 Pre monsoon (1.68 to 34.85 mbgl) Past Monsoon (1.55 to 37.50 mbgl) Long term water level trend in 10 yrs. (2003-2012) Pre monsoon : Rise (0.010 to 2.01m/yr) Fall (0.11 to 2.74m/yr) Post monsoon : Rise (0.011 to 2.56m/yr) Fall (0.01 to 2.21m /yr) 9 GROUND WATER EXPLORATIO N BY CGWB (As on 31-03-2012) No.of wells drilled (EW,OW,PZ,SH,TOTAL) EW OW PZ SH Total 10 GROUND WATER QUALITY CONSTITUENTS Range Min. -

Amreli District Seed Dealer Network Information –Expiry of Licence Sr

COLOUR CELLS INDICATE AMRELI DISTRICT SEED DEALER NETWORK INFORMATION –EXPIRY OF LICENCE SR. DIST. BLOCK DEALER NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT LIC. LICENSING VALID NO CATEGORIES NO AUTHORITY UP TO 1 AMRELI AMRELI HASMUKHBHAI MADHUBHAI PRUTHVI CHEMICALS SEEDS 12 DDA (EXT.) 7/4/2012 BABARIYA HIRAKBAUG SHOPPING, AMRELI 2 AMRELI AMRELI RAJESHBHAI JETHABHAI PRATIKSHA AGRO CHEMICALS SEEDS 24 DDA (EXT.) 7/5/2012 CHATROLA OPERA HOUSE SHOPPING CENTER AMRELI 3 AMRELI AMRELI BHAVESH KANTILAL CHOTALIYA KHODIYAR AGRO CENTER, SHOP-1, SEEDS 36 DDA (EXT.) 5/25/2012 RANGPUR, NR. SWAMINARAYAN TEMPLE, MAIN MARKET, AMRELI 4 AMRELI AMRELI MEHUL BHIKHUBHAI PANSURIYA SATYAM AGRO CENTER SEEDS 38 DDA (EXT.) 5/25/2012 SHOP NO.-1/28, NR. RAMJI TEMPLE AT- CHITTAL 5 AMRELI AMRELI SAMIRBHAI RAMESHBHAI PATEL MANGALAM SEED AGENCY SEEDS 39 DDA (EXT.) 5/25/2012 SHOP NO.-124, OPERA HOUSE, 1ST FLOR, OPP. MARKET YARD, AMRELI 6 AMRELI AMRELI GULABBHAI DEVCHANDBHAI RADHE AGRO AGENCY SEEDS 40 DDA (EXT.) 5/25/2012 DOMADIYA SHOP NO.-53, MARKET YARD ROAD, AMRELI 7 AMRELI AMRELI VIRENDRA DILIP GONDALIYA KRISHNA AGRO CHEMICALS, SEEDS 56 DDA (EXT.) 5/27/2012 HIRAKBAUG SHOPPING CENTER, MARKET YARD ROAD, AMRELI 8 AMRELI AMRELI MANOJ GORDHAN LIMBASIYA AMRUT AGRO CHEMICALS SEEDS 57 DDA (EXT.) 5/27/2012 AT- CHITTAL- NAZARPUR, NR. GOVT CLINIC 9 AMRELI AMRELI CHANDUBHAI BABUBHAI SARANI KHODIYAR TRADERS SEEDS 58 DDA (EXT.) 5/27/2012 SAHJANAND MARKET, G-8, STATION ROAD, AMRELI 10 AMRELI AMRELI HITESHBHAI RAMJIBHAI JAY AMBE AGRO CENTER, PATEL NAGAR-1, SEEDS 59 DDA (EXT.) 5/27/2012 THUMMAR KUKAVAV ROAD, AT- MOTA ANKADIYA 11 AMRELI AMRELI MANOJ VITTHALBHAI RANA KAILASH AGRO AND SEEDS SEEDS 77 DDA (EXT.) 5/28/2012 MAIN MARKET AT- VADERA 12 AMRELI AMRELI HIMMAT GORDHANBHAI BHUMIPUJAN AGRO CENTER SEEDS 78 DDA (EXT.) 5/28/2012 MORADIYA SHOP NO.-68, OPP. -

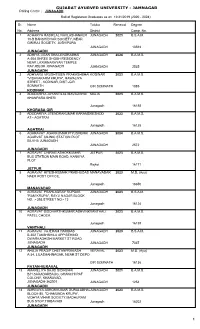

JAMNAGAR Polling Centre : JUNAGADH Roll of Registered Graduates As on 12/31/2019 (2020 - 2024)

GUJARAT AYURVED UNIVERSITY - JAMNAGAR Polling Centre : JUNAGADH Roll of Registered Graduates as on 12/31/2019 (2020 - 2024) Sr. Name Taluka Renewal Degree No. Address District Comp. No. 1 ACHARYA RASIKLAL NAVLASHANKER JUNAGADH 2023 B.S.A.M. 10-B BANSHIDHAR SOCIETY, NEAR GIRIRAJ SOCIETY, JOSHIPURA JUNAGADH 10593 JUNAGADH 2 ADHIYA JIGAR SHAILENDRABHAI JUNAGADH 2024 B.A.M.S. A-204 SHREE SHOBH RESIDENCY NEAR LAXMINARAYAN TEMPLE RAYJIBLOK JUNAGADH JUANGADH 2535 JUNAGADH 3 ADHYARU VRUSHTIBEN PRAKASHBHAI KODINAR 2023 B.A.M.S. "VISHVAKARM KRUPA", RAWALIYA STREET , KODINAR, DIST:-GIR SOMNATH GIR SOMNATH 1885 KODINAR 4 ADODARIYA JAYANTILAL MAVAJIBHAI MALIA 2023 B.A.M.S. KHANPARA SHERI Junagadh 16188 KHORASA GIR 5 ADODARIYA JITENDRAKUMAR KARAMSHIBHAIKESHOD 2023 B.A.M.S. AT:- AGATRAI Junagadh 16128 AGATRAI 6 AGARAVAT JIGARKUMAR PIYUSHBHAI JUNAGADH 2024 B.A.M.S. AGARVAT CILINIC STATION PLOT BILKHA JUNAGADH JUNAGADH 2572 JUNAGADH 7 AGRAVAT CHIRAG ASHOKKUMAR JETPUR 2023 B.A.M.S. BUS STATION MAIN ROAD, KANKIYA PLOT Rajkot 16171 JETPUR 8 AGRAVAT HITESHKUMAR PRABHUDAS MANAVADAR 2023 M.D. (Ayu) NAER POST OFFICE, Junagadh 16650 MANAVADAR 9 AGRAVAT PRAHLADRAY RUPDAS JUNAGADH 2023 B.S.A.M. "RAM KRUPA", RAYJI NAGAR BLOCK NO. :- 393,STREET NO:- 13 Junagadh 16124 JUNAGADH 10 AGRAVAT SIDDHARTHKUMAR ASHVINKUMARVANTHALI 2023 B.A.M.S. PATEL CHOCK Junagadh 16138 VANTHALI 11 AGRAVAT VAJERAM HARIDAS JUNAGADH 2023 B.S.A.M. B-302 TAKSHSHILA APP BEHIND DWARKADHISH MARKET ST ROAD JUNAGADH JUNAGADH 7037 JUNAGADH 12 AHUJA PRADIP CHETANPRAKASH VERAVAL 2023 M.D. (Ayu) A-34, LILASHAHNAGAR, NEAR ST DEPO GIR SOMNATH 16136 PATAN-VERAVAL 13 AMARELIYA SAJID SIDIKBHAI JUNAGADH 2021 B.A.M.S. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : GUJARAT DISTRICT : Ahmadabad Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 VIJAYFARM CHELDA , PIN CODE: 382145, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: 0395646, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NA 10 - 50 NIC 2004 : 1020-Mining and agglomeration of lignite 2 SOMDAS HARGIVANDAS PRAJAPATI KOLAT VILLAGE DIST.AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1990 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. 3 NABIBHAI PIRBHAI MOMIN KOLAT VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1992 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. 4 NANDUBHAI PATEL HEBATPUR TA DASKROI DIST AHMEDABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 5 BODABHAI NO INTONO BHATHTHO HEBATPUR TA DASKROI DIST AHMEDABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 6 NARESHBHAI PRAJAPATI KATHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: 382430, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 7 SANDIPBHAI PRAJAPATI KTHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: 382430, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX 2005 10 - 50 NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 8 JAYSHBHAI PRAJAPATI KATHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX 2005 10 - 50 NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A.