British Music for Clarinet and Piano 1880 to 1945: Repertory and Performance Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

SOMERSET FOLK All Who Roam, Both Young and Old, DECEMBER TOP SONGS CLASSICAL Come Listen to My Story Bold

Folk Singing Broadsht.2 5/4/09 8:47 am Page 1 SOMERSET FOLK All who roam, both young and old, DECEMBER TOP SONGS CLASSICAL Come listen to my story bold. 400 OF ENGLISH COLLECTED BY For miles around, from far and near, YEARS FOLK MUSIC TEN FOLK They come to see the rigs o’ the fair, 11 Wassailing SOMERSET CECIL SHARP 1557 Stationers’ Company begins to keep register of ballads O Master John, do you beware! Christmastime, Drayton printed in London. The Seeds of Love Folk music has inspired many composers, and And don’t go kissing the girls at Bridgwater Fair Mar y Tudor queen. Loss of English colony at Calais The Outlandish Knight in England tunes from Somerset singers feature The lads and lasses they come through Tradtional wassailing 1624 ‘John Barleycorn’ first registered. John Barleycorn in the following compositions, evoking the very From Stowey, Stogursey and Cannington too. essence of England’s rural landscape: can also be a Civil Wars 1642-1650, Execution of Charles I Barbara Allen SONG COLLECTED BY CECIL SHARP FROM visiting 1660s-70s Samuel Pepys makes a private ballad collection. Percy Grainger’s passacaglia Green Bushes WILLIAM BAILEY OF CANNINGTON AUGUST 8TH 1906 Lord Randal custom, Restoration places Charles II on throne was composed in 1905-6 but not performed similar to carol The Wraggle Taggle Gypsies 1765 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry published by FOLK 5 until years later. It takes its themes from the 4 singing, with a Thomas Percy. First printed ballad collection. Dabbling in the Dew ‘Green Bushes’ tune collected from Louie bowl filled with Customs, traditions & glorious folk song Mozart in London As I walked Through the Meadows Hooper of Hambridge, plus a version of ‘The cider or ale. -

RF Annual Report

PRESIDENT'S TEN-YEAR REVIEW ANNUAL REPORT1971 THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION THE ROCKEFELLER mr"nMnftTinN JAN 26 2001 LIBRARY 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation The pages of this report are printed on paper made from recycled fibers THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION 111 WEST 50TH STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10020 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation CONTENTS President's Ten-year Review 1 1971 Grants and Programs 105 Study Awards 143 Organizational Information 151 Financial Statements 161 1971 Appropriations and Payments 173 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation TRUSTEES AND TRUSTEE COMMITTEES April 1971—April 1972 DOUGLAS DILLON* Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER 3RD1 Honorary Chairman BOARD OF TRUSTEES BARRY BINGHAMS VERNON E. JORDAN, JR. FREDERICK SEITZ W. MICHAEL BLUMENTHALS CLARK KERB FRANK STANTON JOHN S. DICKEY MATHILDE KRIM MAURICE F. STRONG* DOUGLAS DILLON ALBERTO LLERAS CAMARGO CYRUS R. VANCE ROBERT H. EBERT BILL MOYEHS THOMAS J. WATSON, JR.4 ROBERT F. GOHEEN JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER 3RD2 CLIFTON R. WHARTON, JR. J. GEORGE HARRAR JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV W. BARRY WOOD, JR.5 THEODORE M. HESBURGH ROBERT V. ROOSA WHITNEY M. YOUNG, JR.6 ARTHUR A. HOUGHTON, JR. NEVIN S. SCRIMSHAW* EXECVTIVE COMMITTEE THE PRESIDENT Chairman ROBERT V. ROOSA THEODORE M. HESBURGH* _ _ _ _ alternate member DOUGLAS DILLON FREDERICK SEITZ ,, „ , PC VERNON E. JORDAN, JR. MATHILDE KRIM* FRANK STANTON alternate member BILL MoYEHS8 CYRUS R. VANCE* NEVJN S- SCRIMSHAW* JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER 3nn2 ROBERT F. GOHEEN alternate member alternate member FINANCE COMMITTEE Through June 30 Beginning July 1 DOUGLAS DILLON Chairman ROBERT V. ROOSA Chairman ROBERT V. ROOSA DOUGLAS DILLON* THOMAS J. -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

Danu Study Guide 11.12.Indd

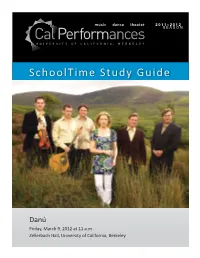

SchoolTime Study Guide Danú Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 am, your class will a end a performance by Danú the award- winning Irish band. Hailing from historic County Waterford, Danú celebrates Irish music at its fi nest. The group’s energe c concerts feature a lively mix of both ancient music and original repertoire. For over a decade, these virtuosos on fl ute, n whistle, fi ddle, bu on accordion, bouzouki, and vocals have thrilled audiences, winning numerous interna onal awards and recording seven acclaimed albums. Using This Study Guide You can prepare your students for their Cal Performances fi eld trip with the materials in this study guide. Prior to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on pages 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the performance. • Discuss the informa on About the Performance & Ar sts and Danú’s Instruments on pages 4-5 with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 6-8 and About Ireland on pages 9-11. • Engage your students in two or more of the ac vi es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding ques ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 9. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sec ons on pages 12 &15. At the performance: Students can ac vely par cipate during the performance by: • LISTENING CAREFULLY to the melodies, harmonies and rhythms • OBSERVING how the musicians and singers work together, some mes playing in solos, duets, trios and as an ensemble • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history, ideas and emo ons expressed through the music • MARVELING at the skill of the musicians • REFLECTING on the sounds and sights experienced at the theater. -

Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: a Reel Crux?

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 139–49 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.8 Note Brett D. Hirsch Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux? A memorable scene in act 3 of Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches (first performed and published 1634) plays out the bewitching of a wedding party and the comedy that ensues. As the party- goers ‘beginne to daunce’ to ‘Selengers round’, the musicians instead ‘play another tune’ and ‘then fall into many’ (F4r).1 With both diabolical interven- tion (‘the Divell ride o’ your Fiddlestickes’) and alcoholic excess (‘drunken rogues’) suspected as causes of the confusion, Doughty instructs the musi- cians to ‘begin againe soberly’ with another tune, ‘The Beginning of the World’, but the result is more chaos, with ‘Every one [playing] a seuerall tune’ at once (F4r). The music then suddenly ceases altogether, despite the fiddlers claiming that they play ‘as loud as [they] can possibly’, before smashing their instruments in frustration (F4v). With neither fiddles nor any doubt left that witchcraft is to blame, Whet- stone calls in a piper as a substitute since it is well known that ‘no Witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire Bag-pipe, for itselfe is able to charme the Divell’ (F4v). Instructed to play ‘a lusty Horne-pipe’, the piper plays with ‘all [join- ing] into the daunce’, both ‘young and old’ (G1r). The stage directions call for the bride and bridegroom, Lawrence and Parnell, to ‘reele in the daunce’ (G1r). At the end of the dance, which concludes the scene, the piper vanishes ‘no bodie knowes how’ along with Moll Spencer, one of the dancers who, unbeknownst to the rest of the party, is the witch responsible (G1r). -

All Around the World the Global Opportunity for British Music

1 all around around the world all ALL British Music for Global Opportunity The AROUND THE WORLD CONTENTS Foreword by Geoff Taylor 4 Future Trade Agreements: What the British Music Industry Needs The global opportunity for British music 6 Tariffs and Free Movement of Services and Goods 32 Ease of Movement for Musicians and Crews 33 Protection of Intellectual Property 34 How the BPI Supports Exports Enforcement of Copyright Infringement 34 Why Copyright Matters 35 Music Export Growth Scheme 12 BPI Trade Missions 17 British Music Exports: A Worldwide Summary The global music landscape Europe 40 British Music & Global Growth 20 North America 46 Increasing Global Competition 22 Asia 48 British Music Exports 23 South/Central America 52 Record Companies Fuel this Global Success 24 Australasia 54 The Story of Breaking an Artist Globally 28 the future outlook for british music 56 4 5 all around around the world all around the world all The Global Opportunity for British Music for Global Opportunity The BRITISH MUSIC IS GLOBAL, British Music for Global Opportunity The AND SO IS ITS FUTURE FOREWORD BY GEOFF TAYLOR From the British ‘invasion’ of the US in the Sixties to the The global strength of North American music is more recent phenomenal international success of Adele, enhanced by its large population size. With younger Lewis Capaldi and Ed Sheeran, the UK has an almost music fans using streaming platforms as their unrivalled heritage in producing truly global recording THE GLOBAL TOP-SELLING ARTIST principal means of music discovery, the importance stars. We are the world’s leading exporter of music after of algorithmically-programmed playlists on streaming the US – and one of the few net exporters of music in ALBUM HAS COME FROM A BRITISH platforms is growing. -

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises a Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920S-1950S)

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 15 April 2019 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s- 1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Professor Laura Downs, European University Institute Professor Catherine Tackley, University of Liverpool Professor Pap Ndiaye, SciencesPo © Veronica Chincoli, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Veronica Chincoli certify that I am the author of the work “Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises: A Transnatioanl Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s). I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

Thomas Hardy and His Rustic “Wessex,” Which Served As the Setting for Many of His Novels and Short Stories

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% $% $ %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% Washington Revels presents 2 English Country Music, Dance, and Drama In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Roberta Gasbarre, artistic/stage director Elizabeth Fulford Miller, music director Jim Alexander, production manager featuring The Mellstock Band with Puddletown Brass Portesham Singers Mellstock Quire Toneborough Teens Casterbridge Children and Cutting Edge Sword Dancers Foggy Bottom Morris Men Lisner Auditorium George Washington University Washington, DC December 4-12, 2010 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% $%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% $ From the Director his year we celebrate an English country Christmas in the spirit of Thomas Hardy and his rustic “Wessex,” which served as the setting for many of his novels and short stories. This fictional region in southwest England is based on the real-world Dorset and its surroundings. One of Hardy’s earliest and most lighthearted works, Under the Greenwood Tree, recalls the characters and pastoral atmosphere of the village of Mellstock, the simple pleasures of country living, and the poignancy of a passing era. I want to share a few thoughts about the creative journey we took from old Mellstock to Lisner today. One of the unexpected pleasures of creating this year’s show was in exploring the rich and colorful world of Hardy’s life and times, as well as his books. We have borrowed or adapted place and character names, as well as poetic and funny lines and scenes, from Under the Greenwood Tree and other writings, especially the seasonal word paintings for which Hardy is beloved. In building an onstage community, Revels always creates multigenerational families. This year, our families have names from Hardy’s books and life—the Longpuddles, for instance. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business.