Cont02.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Du Fay Discography

Guillaume Du Fay Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) builds on the work published in Fanfare in January and March 1980. There are more than three times as many entries in the updated version. It has been published in recognition of the publication of Guillaume Du Fay, his Life and Works by Alejandro Enrique Planchart (Cambridge, 2018) and the forthcoming two-volume Du Fay’s Legacy in Chant across Five Centuries: Recollecting the Virgin Mary in Music in Northwest Europe by Barbara Haggh-Huglo, as well as the new Opera Omnia edited by Planchart (Santa Barbara, Marisol Press, 2008–14). Works are identified following Planchart’s Opera Omnia for the most part. Listings are alphabetical by title in parts III and IV; complete Masses are chronological and Mass movements are schematic. They are grouped as follows: I. Masses II. Mass Movements and Propers III. Other Sacred Works IV. Songs (Italian, French) Secular works are identified as rondeau (r), ballade (b) and virelai (v). Dubious or unauthentic works are italicised. The recordings of each work are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available; then the format of the recording (78, 45, LP, LP quad, MC, CD, SACD), the label, and the issue number(s). Each recorded performance is indicated, if known, as: with instruments, no instruments (n/i), or instrumental only. Album titles of mixed collections are added. ‘Se la face ay pale’ is divided into three groups, and the two transcriptions of the song in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch are arbitrarily designated ‘a’ and ‘b’. -

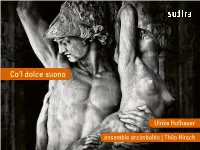

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

Music in the Mid-Fifteenth Century 1440–1480

21M.220 Fall 2010 Class 13 BRIDGE 2: THE RENAISSANCE PART 1: THE MID-FIFTEENTH CENTURY 1. THE ARMED MAN! 2. Papers and revisions 3. The (possible?) English Influence a. Martin le Franc ca. 1440 and the contenance angloise b. What does it mean? c. 6–3 sonorities, or how to make fauxbourdon d. Dunstaple (Dunstable) (ca. 1390–1453) as new creator 4. Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) (ca. 1397–1474) and his music a. Roughly 100 years after Guillaume de Machaut b. Isorhythmic motets i. Often called anachronistic, but only from the French standpoint ii. Nuper rosarum flores iii. Dedication of the Cathedral of Santa Maria de’ Fiore in Florence iv. Structure of the motet is the structure of the cathedral in Florence v. IS IT? Let’s find out! (Tape measures) c. Polyphonic Mass Cycle i. First flowering—Mass of Machaut is almost a fluke! ii. Cycle: Five movements from the ordinary, unified somehow iii. Unification via preexisting materials: several types: 1. Contrafactum: new text, old music 2. Parody: take a secular song and reuse bits here and there (Zachara) 3. Cantus Firmus: use a monophonic song (or chant) and make it the tenor (now the second voice from the bottom) in very slow note values 4. Paraphrase: use a song or chant at full speed but change it as need be. iv. Du Fay’s cantus firmus Masses 1. From late in his life 2. Missa L’homme armé a. based on a monophonic song of unknown origin and unknown meaning b. Possibly related to the Order of the Golden Fleece, a chivalric order founded in 1430. -

June 2015 Broadside

T H E A T L A N T A E A R L Y M U S I C ALLIANCE B R O A D S I D E Volume XV # 4 June, 2015 President’s Message Are we living in the Renaissance? Well, according to the British journalist, Stephen Masty, we are still witnessing new inventions in musical instruments that link us back to the Renaissance figuratively and literally. His article “The 21st Century Renaissance Inventor” [of musical instruments], in the journal “The Imaginative Conservative” received worldwide attention recently regard- ing George Kelischek’s invention of the “KELHORN”. a reinvention of Renaissance capped double-reed instruments, such as Cornamuse, Crumhorn, Rauschpfeiff. To read the article, please visit: AEMA MISSION http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2015/05/the-21st-centurys-great-renaissance-inventor.html. It is the mission of the Atlanta Early Music Alli- Some early music lovers play new replicas of the ance to foster enjoyment and awareness of the histor- Renaissance instruments and are also interested in playing ically informed perfor- the KELHORNs. The latter have a sinuous bore which mance of music, with spe- cial emphasis on music makes even bass instruments “handy” to play, since they written before 1800. Its have finger hole arrangements similar to Recorders. mission will be accom- plished through dissemina- tion and coordination of Yet the sound of all these instruments is quite unlike that information, education and financial support. of the Recorder: The double-reed presents a haunting raspy other-worldly tone. (Renaissance? or Jurassic?) In this issue: George Kelischek just told me that he has initiated The Capped Reed Society Forum for Players and Makers of the Crumhorn, President ’ s Message page 1 Cornamuse, Kelhorn & Rauschpfeiff. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

MUH 5684 Tuesday, Period 3 | Thursday, Periods 3–4 • MUB 232 • Spring 2020 Dr

detail from F-Pn vma ms 1068 | hand of violinist Pierre Baillot | photo by Michael Vincent Introduction to Historical Musicology MUH 5684 Tuesday, Period 3 | Thursday, Periods 3–4 • MUB 232 • Spring 2020 Dr. Michael Vincent • [email protected] • MUB 351 • Thursday & Friday period 5 Please visit me during my office hours. I’m available to discuss our course or issues of professional development. Overview We explore critical approaches to the history of musicology as an academic discipline. The readings provide an overview of fundamental concepts and methodologies, and significant musicological writings representing style periods and conceptual issues. While musicologists traditionally focus on European music in the classical tradition, we will sample scholarship that focuses on a broad range of repertoires. Students will be encouraged to approach the discipline and its history critically. This critical approach will inform your personal work, giving you the tools to investigate your own topic in novel and insightful ways. Each student will choose a “lab rat” at the beginning of the semester: an artistic period, repertoire, performer, social movement, or composer. You will investigate your lab rat using the weekly methodology, diversifying your knowledge of your chosen subject. Your lab rat may grow in unexpected ways as the semester progresses. This course has prerequisites: successful completion of the complete undergraduate music history sequence; graduate student status; and successful completion of the music history entrance exam or the review course. Expectations ❖ Reading You’re expected to come to class having completed all reading on the syllabus for that week. You must be ready to engage with the materials. -

High School Madrigals May 13, 2020

Concert Choir Virtual Learning High School Madrigals May 13, 2020 High School Concert Choir Lesson: May 13, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: students will learn about the history of the madrigal and listen to examples Bell Work ● Complete this google form. A Brief History of Madrigals ● 1501- music could be printed ○ This changed the game! ○ Reading music became expected ● The word “Madrigal” was first used in 1530 and was for musical settings of Italian poetry ● The Italian Madrigal became popular because the emphasis was on the meaning of the text through the music ○ It paved the way to opera and staged musical productions A Brief History of Madrigals ● Composers used text from popular poets at the time ● 1520-1540 Madrigals were written for SATB ○ At the time: ■ Cantus ■ Altus ■ Tenor ■ Bassus ○ More voices were added ■ Labeled by their Latin number ● Quintus (fifth voice) ● Sextus (sixth voice) ○ Originally written for 1 voice on a part A Brief History of Madrigals Homophony ● In the sixteenth century, instruments began doubling the voices in madrigals ● Madrigals began appearing in plays and theatre productions ● Terms to know: ○ Homophony: voices moving together with the same Polyphony rhythm ○ Polyphony: voices moving with independent rhythms ● Early madrigals were mostly homophonic and then polyphony became popular with madrigals A Brief History of Madrigals ● Jacques Arcadelt (1507-1568)was an Italian composer who used both homophony and polyphony in his madrigals ○ Il bianco e dolce cigno is a great example ● Cipriano de Rore -

AMS Newsletter February 2014

AMS NEWSLETTER THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY CONSTITUENT MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES VOLUME XLIV, NUMBER 1 February 2014 ISSN 0402-012X AMS Milwaukee 2014: Not Just 2013 Annual Beer, Brats, and Cheese Meeting: Pittsburgh AMS Milwaukee 2014 venues right in the downtown area, includ- The seventy-ninth Annual Meeting of the 6–9 November ing the Marcus Center for the Performing American Musicological Society took place www.ams-net.org/milwaukee Arts, home of the Milwaukee Symphony, the 7–10 November among the bridges, rivers, Florentine Opera, and the Milwaukee Bal- and hills of Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle. Members of the AMS and the SMT will let. Pabst Theatre and the nearby Riverside The program was packed to the gills, with converge on Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in No- Theatre are home to regular series and the an average of seven concurrent scholarly ses- vember for their annual meetings. Situated Milwaukee Repertory Company. The large sions plus numerous meetings by the Soci- on the west shore of Lake Michigan about Milwaukee Theatre hosts roadshows. The ety’s committees, study groups, and editorial ninety miles north of Chicago, Milwaukee is downtown also boasts two arenas hosting boards, as well as lectures and recitals select- known as the Cream City not because Wis- sporting events and touring acts. The Broad- ed by the Performance Committee. Papers consin is America’s Dairyland, but because way Theatre presents smaller events, includ- and sessions spanned the entire range of the of the ubiquity of cream-colored brick used ing local theater companies and the Skylight field, from the origins of Christian chant to in the city’s oldest buildings. -

Direction 2. Ile Fantaisies

CD I Josquin DESPREZ 1. Nymphes des bois Josquin Desprez 4’46 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 2. Ile Fantaisies Josquin Desprez 2’49 Ensemble Leones Baptiste Romain: fiddle Elisabeth Rumsey: viola d’arco Uri Smilansky: viola d’arco Marc Lewon: direction 3. Illibata dei Virgo a 5 Josquin Desprez 8’48 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 4. Allégez moy a 6 Josquin Desprez 1’07 5. Faulte d’argent a 5 Josquin Desprez 2’06 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction 6. La Spagna Josquin Desprez 2’50 Syntagma Amici Elsa Frank & Jérémie Papasergio: shawms Simen Van Mechelen: trombone Patrick Denecker & Bernhard Stilz: crumhorns 7. El Grillo Josquin Desprez 1’36 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction Missa Lesse faire a mi: Josquin Desprez 8. Sanctus 7’22 9. Agnus Dei 4’39 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 10. Mille regretz Josquin Desprez 2’03 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 11. Mille regretz Luys de Narvaez 2’20 Rolf Lislevand: vihuela 2: © CHRISTOPHORUS, CHR 77348 5 & 7: © HARMONIA MUNDI, HMC 901279 102 ITALY: Secular music (from the Frottole to the Madrigal) 12. Giù per la mala via (Lauda) Anonymous 6’53 EnsembleDaedalus Roberto Festa: direction 13. Spero haver felice (Frottola) Anonymous 2’24 Giovanne tutte siano (Frottola) Vincent Bouchot: baritone Frédéric Martin: lira da braccio 14. Fammi una gratia amore Heinrich Isaac 4’36 15. Donna di dentro Heinrich Isaac 1’49 16. Quis dabit capiti meo aquam? Heinrich Isaac 5’06 Capilla Flamenca Dirk Snellings: direction 17. Cor mio volunturioso (Strambotto) Anonymous 4’50 Ensemble Daedalus Roberto Festa: direction 18. -

An Historical and Analytical Study of Renaissance Music for the Recorder and Its Influence on the Later Repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Woodhill, Vanessa, An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire, Master of Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2179 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF RENAISSANCE MUSIC FOR THE RECORDER AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LATER REPERTOIRE by VANESSA WOODHILL. B.Sc. L.T.C.L (Teachers). F.T.C.L A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong. "u»«viRsmr •*"! This thesis is submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wotlongong in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or similar institution. Copyright for the extracts of musical works contained in this thesis subsists with a variety of publishers and individuals. Further copying or publishing of this thesis may require the permission of copyright owners. Signed SUMMARY The material in this thesis approaches Renaissance music in relation to the recorder player in three ways. -

Download Discantus Artistic Projects

SPEEDMEETINGS SUBSCRIPTION FORM COMPANY : Ensemble Discantus / Centre de musique médiévale de Paris Brigitte LESNE (in french and spanish, available until 15:00) Anne PIFFARD (English), Alain GENUYS (French) e-mail : [email protected] - tél : 0033 1 45 80 74 49 Describe your company in a few words : Discantus is women vocal ensemble that brings alive the vocal repertoire, primarily sacred, of the Middle Ages from the first Western musical notation of the 9th century up to the 15th century. Founded in 1989 under the direction of Brigitte Lesne, it brings together passionate singers from diverse backgrounds capable of adopting a vocal style appropriate to the medieval repertoire, uniting unique individual timbres to form a coherent ensemble sound. Since the 2000’s, Discantus’ handbells became like the "signature" of the ensemble. Invited to the most prestigious festivals, Discantus performs regularly in France, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe (Croatia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland) and as far as Fes in Morocco, Beyrouth in Lebanon, New York, Perth, and also in Colombia. The 13th recording, "the Argument of Beauty" (sacred polyphonies by Gilles Binchois, at æon recordings) was rewarded as 2010 best recordings of the year by Le Monde newspaper. In 2014, « Music for a King » - also by æon – alternates 11th century repertoire with two pieces commissioned to young composers using texts of Boethius. Discantus keeps enlarging it's repertoire with two new programs incorporating typical medieval stringed instruments (harp, hurdy-gurdy, psaltery, fiddle) played by the singers themselves: "A path to the field of stars, pligrim's songs" and "Santa Maria, At the court of Alfonso el Sabio". -

BH Program FINAL

MUSIC BEFORE 1800 Louise Basbas, Director Blue Heron Christmas at the Courts of 15th-Century France & Burgundy Scott Metcalfe, director and harp Jennifer Ashe, Pamela Dellal, Martin Near, Daniela Tosic Michael Barrett, Owen McIntosh, Jason McStoots, Stefan Reed, Mark Sprinkle, Sumner Tompson Cameron Beauchamp, Paul Guttry Laura Jeppesen, vielle and rebec; Charles Weaver, lute and voice Advent O clavis David (O-antiphon for December 20) plainchant Factor orbis Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 - 1505) O virgo virginum (O-antiphon for December 24) plainchant O virgo virginum Josquin Desprez (c. 1455 - 1521) Conditor alme siderum (alternatim hymn for Advent) Guillaume Du Fay (c. 1397 - 1474) Ave Maria gratia dei plena Antoine Brumel (c. 1460 - c. 1512) Christmas O admirabile commercium / Verbum caro factum est Johannes Regis (c. 1425 - 1426) INTERMISSION Christmas Letabundus (Christmas sequence) Guillaume Du Fay Praeter rerum seriem Adrian Willaert (c. 1490 - 1562 New Year’s Day La plus belle et doulce figure Nicolas Grenon (c. 1380 - 1456) Dieu vous doinst bon jour et demy Guillaume Malbecque (c. 1400 - 1465) Dame excellent ou sont bonté, scavoir Baude Cordier (d. 1397/8?) De tous biens playne (instrumental) Johannes Tinctoris (c. 1435 - 1511?) Margarite, fleur de valeur Gilles Binchois (c. 1400 - 1460) Ce jour de l’an voudray joie mener Guillaume Du Fay Christmas Gloria Spiritus et alme Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370 - 1412) Nato canunt omnia Antoine Brumel Tis concert is sponsored, in part, by the Florence Gould Foundation, Music Before 1800’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.