Lake Champlain Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn College and Graduate School of the City University of NY, Brooklyn, NY 11210 and Northeastern Science Foundation Affiliated with Brooklyn College, CUNY, P.O

FLYSCH AND MOLASSE OF THE CLASSICAL TACONIC AND ACADIAN OROGENIES: MODELS FOR SUBSURFACE RESERVOIR SETTINGS GERALD M. FRIEDMAN Brooklyn College and Graduate School of the City University of NY, Brooklyn, NY 11210 and Northeastern Science Foundation affiliated with Brooklyn College, CUNY, P.O. Box 746, Troy, NY 12181 ABSTRACT This field trip will examine classical sections of the Appalachians including Cambro-Ordovician basin-margin and basin-slope facies (flysch) of the Taconics and braided and meandering stteam deposits (molasse) of the Catskills. The deep water settings are part of the Taconic sequence. These rocks include massive sandstones of excellent reservoir quality that serve as models for oil and gas exploration. With their feet, participants may straddle the classical Logan's (or Emmon 's) line thrust plane. The stream deposits are :Middle to Upper Devonian rocks of the Catskill Mountains which resulted from the Acadian Orogeny, where the world's oldest and largest freshwater clams can be found in the world's oldest back-swamp fluvial facies. These fluvial deposits make excellent models for comparable subsurface reservoir settings. INTRODUCTION This trip will be in two parts: (1) a field study of deep-water facies (flysch) of the Taconics, and (2) a field study of braided- and meandering-stream deposits (molasse) of the Catskills. The rocks of the Taconics have been debated for more than 150 years and need to be explained in detail before the field stops make sense to the uninitiated. Therefore several pages of background on these deposits precede the itinera.ry. The Catskills, however, do not need this kind of orientation, hence after the Taconics (flysch) itinerary, the field stops for the Catskills follow immediately without an insertion of background informa tion. -

Introduction

Introduction This is the fourteenth edition of Profiles of New York State—Facts, Figures & Statistics for 2,570 Populated Places in New York. As with the other titles in our State Profiles series, it was built with content from Grey House Publishing’s award-winning Profiles of America—a 4-volume compilation of data on more than 43,000 places in the United States. We have included the New York chapter from Profiles of America, and added several new chapters of demographic information and ranking sections, so that Profiles of New York State is the most comprehensive portrait of the state of New York ever published. Profiles of New York State provides data on all populated communities and counties in the state of New York for which the US Census provides individual statistics. This edition also includes profiles of 444 unincorporated places and neighborhoods (i.e. Flushing, Queens) based on US Census data by zip code. This premier reference work includes five major sections that cover everything from Education to Ethnic Backgrounds to Climate. All sections include Comparative Statistics or Rankings. A section called About New York at the front of the book includes detailed narrative and colorful photos and maps. Here is an overview of each section: 1. About New York This 4-color section gives the researcher a real sense of the state and its history. It includes a Photo Gallery, and comprehensive sections on New York’s Government, Timeline of New York History, Land and Natural Resources, New York State Energy Profile and Demographic Maps. These 42 pages, with the help of photos, maps and charts, anchor the researcher to the state, both physically and politically. -

Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Agency of Natural Resources

Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Agency of Natural Resources WATER INVESTMENT DIVISION National Life Building, DAVIS 3 1 National Life Drive Montpelier, VT 05620-3510 FAX: (802)828-1552 Ms. Megan Moir, Assistant DPW Director of Water Resources Authorized Representative City of Burlington 234 Penny Lane Burlington, VT 05401 January 14, 2021 Expiration Date: January 14, 2026 Re: Manhattan Drive Outfall Repairs Project Vermont/ USEPA Clean Water Revolving Loan Number RF1‐2xx (Pending) Notice of Intent to Issue a Finding of No Significant Impact Dear Megan: The Department of Environmental Conservation intends to issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) for the Manhattan Drive Outfall Repairs Project. The project has positive environmental impacts consisting of the reduction of erosion and sediment movement into the adjacent waters of the state and improved reliability and resiliency of the adjacent municipal sewer and stormwater systems. This project additionally involves impacts to wetlands and floodplains in the form of permitted wetlands impacts and de minimus floodplain impacts. Otherwise, this project may have been eligible for Categorical Exclusion from detailed environmental review; additionally, the direct and indirect environmental effects of the project are still not significant enough to necessitate an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The Department's environmental review procedures require a 30‐day public comment period following the issuance of a Notice of Intent to Issue a Finding of No Significant Impact. If no public comments received during that period demonstrate that this Notice of Intent is in error, then the Finding of No Significant Impact will become effective. Page 2 of 2 Megan Moir, Authorized Representative, City of Burlington Manhattan Drive Outfall Repairs Finding of No Significant Impact January 14, 2021 Copies of documents supporting a Finding of No Significant Impact are enclosed. -

Dams and Reservoirs in the Lake Champlain Richelieu River Basin

JUST THE FACTS SERIES June 2019 DAMS AND RESERVOIRS IN THE LAKE CHAMPLAIN RICHELIEU RIVER BASIN MYTH Water released from tributary dams in the United States causes flooding in Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River. FACT Water levels in Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River Generally, mass releases of water from flood control are primarily affected by precipitation from rain or dams are avoided. In addition to compromising the snowmelt. structural integrity of the dams, mass releases would also endanger the very communities that these dams are built Because of its size, Lake Champlain can store a lot of to protect. water; the flood control dams and reservoirs in the basin, which are very small in comparison to the lake, do not When conditions force the release of more water than significantly change water levels of the lake and river as hydropower plants can handle, the increase in water they release water. levels immediately below the dam will be much greater than the increase on Lake Champlain. This is true even during high water and flooding events. Consider, for instance, when Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River experienced extreme flooding between April and June 2011, the additional releases flowing from Waterbury Reservoir—the largest flood control reservoir in the Vermont portion of the basin, contributed less than 2 centimetres (¾ inch) to the elevation of Lake Champlain and the upper Richelieu River. International Lake Champlain-Richelieu River Study Board FACT FACT Dams in the US portion of the basin are built for one of Waterbury Reservoir in Vermont is the largest reservoir two purposes: flood control or hydroelectric power. -

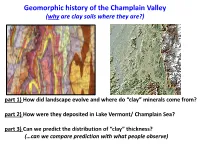

Champlain Valley (Why Are Clay Soils Where They Are?)

Geomorphic history of the Champlain Valley (why are clay soils where they are?) part 1) How did landscape evolve and where do “clay” minerals come from? part 2) How were they deposited in Lake Vermont/ Champlain Sea? part 3) Can we predict the distribution of “clay” thickness? (…can we compare prediction with what people observe) 500,000,000 years Today ~500,000,000 years: Sediments of “Champlain Valley Sequence” deposited on shoreline of ancient ocean Monkton quartzite + Taconic Slates Limestones + Marbles ~460,000,000 years: Collision of island arc causes thrusting + metamorphism Champlain Thrust Fault Champlain Thrust: -Exposed at Snake Mtn + Mt. Philo -delineates boundary between “low” and “mid” grade metamorphic rocks -Marbles pf middlebury syncline folded along back of thrust -Topography of Addison County reflects erodibility of bedrock: T1: lower surface: “low grade” sedimentary rocks below thrust (e.g. shale) T2: upper surface: “mid grade” meta-sedimentary rocks above thrust (e.g. marble) Green Mountains= “high grade” metamorphic rocks (e.g. schist and gneiss) T1 T2 Green Mtn gneiss Geologic map of Addison County Taconics Part 2: How were clays deposited in Lake Vermont and the Champlain Sea? 500,000,000 years Today ~96,000 - 20,000 years (i.e. yesterday…): Champlain Valley sat below 1-3 km of ice Soils and clay minerals from previous inter-glacial cycles were stripped by advancing glaciers Rocks were ground into “clay size fraction” and trapped under ice retreating glacial ice withdrew from Champlain Valley between ~14-13 kyr Many depositional features in Champlain Valley record ice retreat -Layers of “basal till” deposited beneath ice sheets (coarse, angular, poorly sorted debris) -Meltwater streams flow between glacier and hillslopes -Sedimentary deposits accumulate, leaving ‘kame terraces’ when glacier retreats Lake Vermont had 2+ stages: Coveville: Ice dammed in So. -

Aquatic Fish Report

Aquatic Fish Report Acipenser fulvescens Lake St urgeon Class: Actinopterygii Order: Acipenseriformes Family: Acipenseridae Priority Score: 27 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Gobal Rank: G3G4 — Vulnerable (uncertain rank) State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Ouachita Mountains Arkansas Valley South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Acipenser fulvescens Lake Sturgeon 362 Aquatic Fish Report Ecobasins Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - Arkansas River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - St. Francis River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - White River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (Lake Chicot) - Mississippi River Habitats Weight Natural Littoral: - Large Suitable Natural Pool: - Medium - Large Optimal Natural Shoal: - Medium - Large Obligate Problems Faced Threat: Biological alteration Source: Commercial harvest Threat: Biological alteration Source: Exotic species Threat: Biological alteration Source: Incidental take Threat: Habitat destruction Source: Channel alteration Threat: Hydrological alteration Source: Dam Data Gaps/Research Needs Continue to track incidental catches. Conservation Actions Importance Category Restore fish passage in dammed rivers. High Habitat Restoration/Improvement Restrict commercial harvest (Mississippi River High Population Management closed to harvest). Monitoring Strategies Monitor population distribution and abundance in large river faunal surveys in cooperation -

A Fish Habitat Partnership

A Fish Habitat Partnership Strategic Plan for Fish Habitat Conservation in Midwest Glacial Lakes Engbretson Underwater Photography September 30, 2009 This page intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. BACKGROUND 7 II. VALUES OF GLACIAL LAKES 8 III. OVERVIEW OF IMPACTS TO GLACIAL LAKES 9 IV. AN ECOREGIONAL APPROACH 14 V. MULTIPLE INTERESTS WITH COMMON GOALS 23 VI. INVASIVES SPECIES, CLIMATE CHANGE 23 VII. CHALLENGES 25 VIII. INTERIM OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS 26 IX. INTERIM PRIORITY WATERSHEDS 29 LITERATURE CITED 30 APPENDICES I Steering Committee, Contributing Partners and Working Groups 33 II Fish Habitat Conservation Strategies Grouped By Themes 34 III Species of Greatest Conservation Need By Level III Ecoregions 36 Contact Information: Pat Rivers, Midwest Glacial Lakes Project Manager 1601 Minnesota Drive Brainerd, MN 56401 Telephone 218-327-4306 [email protected] www.midwestglaciallakes.org 3 Executive Summary OUR MISSION The mission of the Midwest Glacial Lakes Partnership is to work together to protect, rehabilitate, and enhance sustainable fish habitats in glacial lakes of the Midwest for the use and enjoyment of current and future generations. Glacial lakes (lakes formed by glacial activity) are a common feature on the midwestern landscape. From small, productive potholes to the large windswept walleye “factories”, glacial lakes are an integral part of the communities within which they are found and taken collectively are a resource of national importance. Despite this value, lakes are commonly treated more as a commodity rather than a natural resource susceptible to degradation. Often viewed apart from the landscape within which they occupy, human activities on land—and in water—have compromised many of these systems. -

2009 Land Management Plan

2009 LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN (Updated Annual Harvest Plan -2014) Itasca County Land Department 1177 LaPrairie Avenue Grand Rapids, MN 55744-3322 218-327-2855 ● Fax: 218-327-4160 LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Itasca County Land Department Acknowledgements This Land Management Plan was produced by Itasca County Land Department employees Garrett Ous, Dave Marshall, Michael Gibbons, Adam Olson, Bob Scheierl, Roger Clark, Kory Cease, Steve Aysta, Tim Stocker, Perry Leone, Wayne Perreault, Blair Carlson, Loren Eide, Bob Rother, Andrew Brown, Del Inkman, Darlene Brown and Meg Muller. Thank you to all the citizens for their sincere input and review during the public involvement process. And thank you to Itasca County Commissioners Lori Dowling, Karen Burthwick, Rusty Eichorn, Catherine McLynn and Mark Mandich for their vision and final approval of this document. Foreword This land management plan is designed for providing vision and direction to guide strategic and operational programs of the Land Department. That vision and direction reflects a long standing connection with local economic, educational and social programs. The Land Department is committed to ensuring that economic benefits and environmental integrity are available to both present and future generations. That will be accomplished through actively managing county land and forests for a balance of benefits to the citizens and for providing them with a sustained supply of quality products and services. The Department will apply quality forestland stewardship practices, employ modern technology and information, and partner with other forest organizations to provide citizens with those quality products and services. ________________________________ Garrett Ous September, 2009 Itasca County Land Commissioner 1177 LaPrairie Avenue Grand Rapids, MN 55744-3322 218-327-2855 ● Fax: 218-327-4160 ICLD - LMP Section i., page 1 of 3 Itasca County Land Department Land Management Plan Table of Contents i. -

Wholesale Sales Reps by State Effective July 1, 2021 "Independent

Wholesale Sales Reps by State effective July 1, 2021 "Independent" Customers in these Sales Representative Phone E-mail states Alabama Renee Cohen 802-864-1808 ext. 2151 [email protected] Alaska Market 2 Market 800-228-2157 [email protected] Arizona Skotak & Company (602) 538-1740 [email protected] Arkansas Renee Cohen 802-864-1808 ext. 2151 [email protected] Renaissance & GMI distributor for everyday/ seasonal = LCC Team and California Barbara Emmerich (Nor CA select accts) (707) 526-1592 [email protected] Colorado CA Fortune (630) 539-3100 [email protected] Connecticut Travis Edwards 617-913-8062 [email protected] Delaware Travis Edwards 617-913-8063 [email protected] District of Columbia Travis Edwards 617-913-8063 [email protected] Florida The Cristol Group 954-486-4129 [email protected] Georgia Renee Cohen 802-864-1808 ext. 2151 [email protected] Hawaii LCC sales/customer service team Idaho CA Fortune (630) 539-3100 [email protected] Illinois Specialty Food Sales 847-763-8601 [email protected] Indiana Renee Cohen 802-864-1808 ext. 2151 [email protected] Iowa Maria Green & Associates 800-509-9775 [email protected] Kansas Maria Green & Associates 800-509-9775 [email protected] Kentucky Renee Cohen 802-864-1808 ext. 2151 [email protected] Louisiana Renee Cohen 802-864-1808 ext. 2151 [email protected] Maine Giovanni Cassano 802-557-8110 -

Research Bibliography on the Industrial History of the Hudson-Mohawk Region

Research Bibliography on the Industrial History of the Hudson-Mohawk Region by Sloane D. Bullough and John D. Bullough 1. CURRENT INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGY Anonymous. Watervliet Arsenal Sesquicentennial, 1813-1963: Arms for the Nation's Fighting Men. Watervliet: U.S. Army, 1963. • Describes the history and the operations of the U.S. Army's Watervliet Arsenal. Anonymous. "Energy recovery." Civil Engineering (American Society of Civil Engineers) 54 (July 1984): 60- 61. • Describes efforts of the City of Albany to recycle and burn refuse for energy use. Anonymous. "Tap Industrial Technology to Control Commercial Air Conditioning." Power 132 (May 1988): 91–92. • The heating, ventilation and air–conditioning (HVAC) system at the Empire State Plaza in Albany is described. Anonymous. "Albany Scientist Receives Patent on Oscillatory Anemometer." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 70 (March 1989): 309. • Describes a device developed in Albany to measure wind speed. Anonymous. "Wireless Operation Launches in New York Tri- Cities." Broadcasting 116 10 (6 March 1989): 63. • Describes an effort by Capital Wireless Corporation to provide wireless premium television service in the Albany–Troy region. Anonymous. "FAA Reviews New Plan to Privatize Albany County Airport Operations." Aviation Week & Space Technology 132 (8 January 1990): 55. • Describes privatization efforts for the Albany's airport. Anonymous. "Albany International: A Century of Service." PIMA Magazine 74 (December 1992): 48. • The manufacture and preparation of paper and felt at Albany International is described. Anonymous. "Life Kills." Discover 17 (November 1996): 24- 25. • Research at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy on the human circulation system is described. Anonymous. "Monitoring and Data Collection Improved by Videographic Recorder." Water/Engineering & Management 142 (November 1995): 12. -

Taconic Physiography

Bulletin No. 272 ' Series B, Descriptive Geology, 74 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR . UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR 4 t TACONIC PHYSIOGRAPHY BY T. NELSON DALE WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1905 CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transinittal......................................._......--..... 7 Introduction..........I..................................................... 9 Literature...........:.......................... ........................... 9 Land form __._..___.._.___________..___._____......__..__...._..._--..-..... 18 Green Mountain Range ..................... .......................... 18 Taconic Range .............................'............:.............. 19 Transverse valleys._-_-_.-..._.-......-....___-..-___-_....--_.-.._-- 19 Longitudinal valleys ............................................. ^...... 20 Bensselaer Plateau .................................................... 20 Hudson-Champlain valley................ ..-,..-.-.--.----.-..-...... 21 The Taconic landscape..................................................... 21 The lakes............................................................ 22 Topographic types .............,.....:..............'.................... 23 Plateau type ...--....---....-.-.-.-.--....-...... --.---.-.-..-.--... 23 Taconic type ...-..........-........-----............--......----.-.-- 28 Hudson-Champlain type ......................"...............--....... 23 Rock material..........................'.......'..---..-.....-...-.--.-.-. 23 Harder rocks ....---...............-.-.....-.-...--.-......... -

17 Major Drainage Basins

HUC 8 HYDROLOGIC UNIT NAME CLINTON 04120101 Chautauqua-Conneaut FRANKLIN 04150409 CHAMPLAIN MASSENA FORT COVINGTON MOOERS ST LAWRENCE CLINTON 04120102 Cattaraugus BOMBAY WESTVILLE CONSTABLE CHATEAUGAY NYS Counties & BURKE LOUISVILLE 04120103 Buffalo-Eighteenmile BRASHER 04150308 CHAZY ALTONA ELLENBURG BANGOR WADDINGTON NORFOLK MOIRA 04120104 Niagara ESSEX MALONE DEC Regions JEFFERSON 6 04150307 BEEKMANTOWN MADRID 05010001 Upper Allegheny LAWRENCE BELLMONT STOCKHOLM DANNEMORA BRANDON DICKINSON PLATTSBURGH LEWIS OGDENSBURG CITY LISBON 05010002 Conewango 5 PLATTSBURGH CITY HAMILTON POTSDAM SCHUYLER FALLS SARANAC 05010004 French WARREN OSWEGATCHIE DUANE OSWEGO 04150306 PERU 04130001 Oak Orchard-Twelvemile CANTON PARISHVILLE ORLEANS WASHINGTON NIAGARA DE PEYSTER ONEIDA MORRISTOWN HOPKINTON WAVERLY PIERREPONT FRANKLIN 04140101 Irondequoit-Ninemile AUSABLE MONROE WAYNE BLACK BROOK FULTON SARATOGA DEKALB HERKIMER BRIGHTON GENESEE SANTA CLARA CHESTERFIELD 04140102 Salmon-Sandy ONONDAGA NYS Major 04150406 MACOMB 04150304 HAMMOND ONTARIO MADISON MONTGOMERY RUSSELL 04150102 Chaumont-Perch ERIE SENECA CAYUGA SCHENECTADY HERMON WILLSBORO ST ARMAND WILMINGTON JAY WYOMING GOUVERNEUR RENSSELAER ALEXANDRIA CLARE LIVINGSTON YATES 04130002 Upper Genesee OTSEGO ROSSIE COLTON CORTLAND ALBANY ORLEANS 04150301 04150404 SCHOHARIE ALEXANDRIA LEWIS 7 EDWARDS 04150408 CHENANGO FOWLER ESSEX 04130003 Lower Genesee 8 TOMPKINS CLAYTON SCHUYLER 9 4 THERESA 04150302 TUPPER LAKE HARRIETSTOWN NORTH ELBA CHAUTAUQUA CATTARAUGUS PIERCEFIELD 02050104 Tioga ALLEGANY STEUBEN