Shown to Be Contentious, Or at Acknowledged in International Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSUE 2/2019 • JULY 2019 KDN No

ISSUE 2/2019 • JULY 2019 KDN No. PP 13699/01/2013 (031337) LEGAL INSIGHTS A SKRINE NEWSLETTER CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM 1 Message from the Editor-in- THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Chief 2 Announcements There were several significant developments in the Malaysian legal landscape since we ARTICLES published the previous issue of our Newsletter four months ago. In the first ever sitting 2 Filling the Gaps in Trade of a nine-member panel, the Federal Court held by a 5:4 majority that the civil courts Marks: The Trademarks Bill 2019 in Malaysia are bound by the rulings issued by the Syariah Advisory Council of Bank Negara Malaysia under sections 56 and 57 of the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009. 8 The Companies (Amendment) Bill 2019 12 Developments in Statutory In July 2019, the Malaysian Parliament passed two significant pieces of legislation. The Adjudication 2018 first is the Trademarks Bill 2019. This Bill is significant as it will introduce many new 16 Check Your Privilege concepts into our trademarks law when it comes into force. The other is the Companies (Amendment) Bill 2019 which will bring about much welcomed clarifications on several 20 Renewable Energy: The Rising Sun provisions of the Companies Act 2016. 22 Beefing Up Aviation Security The decision of the Federal Court and the two pieces of legislation mentioned above are discussed in this issue of our Newsletter. CASE COMMENTARIES Also featured in this issue are two other noteworthy decisions of the Federal Court; 10 Retention Sums – Is it Really Yours? – SK M&E Bersekutu the first determined whether retention sums under a construction contract are trust Sdn Bhd v Pembinaan moneys, and the second, whether a solicitor who unknowingly acts for a fraudster in a Legenda Unggul Sdn Bhd land fraud case owes a duty of care to the real owner of the land. -

Flooding Projections from Elevation and Subsidence Models for Oil Palm Plantations in the Rajang Delta Peatlands, Sarawak, Malaysia

Flooding projections from elevation and subsidence models for oil palm plantations in the Rajang Delta peatlands, Sarawak, Malaysia Flooding projections from elevation and subsidence models for oil palm plantations in the Rajang Delta peatlands, Sarawak, Malaysia Report 1207384 Commissioned by Wetlands International under the project: Sustainable Peatlands for People and Climate funded by Norad May 2015 Flooding projections for the Rajang Delta peatlands, Sarawak Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Land subsidence in peatlands ................................................................................. 8 1.2 Assessing land subsidence and flood risk in tropical peatlands ............................... 8 1.3 This report............................................................................................................. 10 2 The Rajang Delta - peat soils, plantations and subsidence .......................................... 11 2.1 Past assessments of agricultural suitability of peatland in Sarawak ...................... 12 2.2 Current flooding along the Sarawak coast ............................................................. 16 2.3 Land cover developments and status .................................................................... 17 2.4 Subsidence rates in tropical peatlands .................................................................. 23 3 Digitial Terrain Model of the Rajang Delta and coastal -

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 170(H): NATIONAL PERPETUITY STANDARDS for FEDERALLY SUBSIDIZED CONSERVATION EASEMENTS PART 1: the STANDARDS

INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 170(h): NATIONAL PERPETUITY STANDARDS FOR FEDERALLY SUBSIDIZED CONSERVATION EASEMENTS PART 1: THE STANDARDS Nancy A. McLaughlin Editors Synopsis: This Article is the first of two companion articles that (i) analyze the requirements in Internal Revenue Code section 170(h) that a deductible conservation easement be granted in perpetuity and its conservation purpose be protected in perpetuity and (ii) compare those requirements to state law provisions addressing the transfer, modification, or termination of conservation easements. This Article discusses the historical development of the federal charitable income tax deduction for conservation easement donations, the legislative history of section 170(h), and the Treasury Regulations interpreting that section. It explains that section 170(h) and the Treasury Regulations contain a complex web of requirements intended to ensure that a federal subsidy is provided only with respect to conservation easements that permanently protect unique or otherwise significant properties. Such requirements are also intended to ensure that, in the unlikely event changed conditions make continued use of the subject property for conservation or historic preservation purposes impossible or impractical and the easement is extinguished in a state court proceeding, the holder will receive proceeds and use those proceeds to replace the lost conservation or historic values on behalf of the public. The companion article, which will be published in the Winter 2010 edition of this journal, surveys the over one hundred statutes extant in the fifty states and the District of Columbia that authorize the creation or acquisition of conservation easements. That article explains that such statutes contain widely divergent transfer, modification, and termination provisions that were not, for the most part, crafted with an eye toward complying with federal tax law perpetuity requirements. -

Jurisdiction of a Tribunal - Extinguishment

Jurisdiction of a tribunal - extinguishment De Lacey v Juunyjuwarra People [2004] QCA 297 Davies JA, Mackenzie and Mullins JJ, 13 August 2004 Issue The main issue before the court was whether the Land and Resources Tribunal (LRT) established under the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) (the Act) had jurisdiction to determine whether the Starcke Pastoral Holdings Acquisition Act 1994 (Qld) extinguished native title in relation to an area the subject of a claimant application. Background In December 2003, Ralph De Lacey, an applicant for a ‘high impact’ exploration permit, applied to the LRT for a determination as to whether or not it had jurisdiction to decide that native title has been extinguished by the Act. On 27 February 2004, the LRT decided that it did have jurisdiction to determine that question and that it would be determined as a preliminary issue. An appeal against that decision was filed in the Supreme Court of Queensland by the State of Queensland. Decision Davies JA (with MacKenzie and Mullins JJ agreeing) held that: • there was no provision in the Act that contemplated an application to the LRT as was made in December 2003 or any decision by the LRT of the question stated in that application; • the LRT plainly saw that its jurisdiction to make the decision which it did make, was found in, or implied by, s. 669 of the Act, which governed the making of a ‘native title issues decision’ by the LRT. Where, in a proceeding otherwise properly instituted in a tribunal, there remains a condition upon the fulfilment or existence of which the jurisdiction of the tribunal exists (here, non-extinguishment of native title), the fulfilment or existence of that condition remains an outstanding question until it has been decided by a court competent to decide it: Parisienne Basket Shoes Pty Ltd v Whyte (1938) 59 CLR 359 at 391. -

Extinguishment of Agency General Condition Revocation Withdrawal Of

Extinguishment of Agency General condition Revocation Withdrawal of agent Death of the Principal Death of the Agent CASES Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. L-36585 July 16, 1984 MARIANO DIOLOSA and ALEGRIA VILLANUEVA-DIOLOSA, petitioners, vs. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS, and QUIRINO BATERNA (As owner and proprietor of QUIN BATERNA REALTY), respondents. Enrique L. Soriano for petitioners. Domingo Laurea for private respondent. RELOVA, J.: Appeal by certiorari from a decision of the then Court of Appeals ordering herein petitioners to pay private respondent "the sum of P10,000.00 as damages and the sum of P2,000.00 as attorney's fees, and the costs." This case originated in the then Court of First Instance of Iloilo where private respondents instituted a case of recovery of unpaid commission against petitioners over some of the lots subject of an agency agreement that were not sold. Said complaint, docketed as Civil Case No. 7864 and entitled: "Quirino Baterna vs. Mariano Diolosa and Alegria Villanueva-Diolosa", was dismissed by the trial court after hearing. Thereafter, private respondent elevated the case to respondent court whose decision is the subject of the present petition. The parties — petitioners and respondents-agree on the findings of facts made by respondent court which are based largely on the pre-trial order of the trial court, as follows: PRE-TRIAL ORDER When this case was called for a pre-trial conference today, the plaintiff, assisted by Atty. Domingo Laurea, appeared and the defendants, assisted by Atty. Enrique Soriano, also appeared. A. -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

A Study on Trend of Logs Production and Export in the State of Sarawak, Malaysia

International Journal of Marketing Studies www.ccsenet.org/ijms A Study on Trend of Logs Production and Export in the State of Sarawak, Malaysia Pakhriazad, H.Z. (Corresponding author) & Mohd Hasmadi, I Department of Forest Management, Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8946-7225 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study was conducted to determine the trend of logs production and export in the state of Sarawak, Malaysia. The trend of logs production in this study referred only to hill and peat swamp forest logs production with their species detailed production. The trend of logs export was divided into selected species and destinations. The study covers the analysis of logs production and export for a period of ten years from 1997 to 2006. Data on logs production and export were collected from statistics published by the Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation (Statistic of Sarawak Timber and Timber Product), Sarawak Timber Association (Sarawak Timber Association Review), Hardwood Timber Sdn. Bhd (Warta) and Malaysia Timber Industry Board (MTIB). The trend of logs production and export were analyzed using regression model and times series. In addition, the relation between hill and peat swamp forest logs production with their species and trend of logs export by selected species and destinations were conducted using simple regression model and descriptive statistical analysis. The results depicted that volume of logs production and export by four major logs producer (Sibu division, Bintulu division, Miri division and Kuching division) for hill and peat swamp forest showed a declining trend. Result showed that Sibu division is the major logs producer for hill forest while Bintulu division is the major producer of logs produced for the peat swamp forest. -

11-02/2014(W) BETWEEN Deutsche Bank (Malaysia)

DALAM MAHKAMAH PERSEKUTUAN MALAYSIA (BIDANGKUASA RAYUAN) RAYUAN SIVIL NO. 02(f)-11-02/2014(W) BETWEEN Deutsche Bank (Malaysia) Bhd … APPELLANT AND 1. MBf Holdings Berhad 2. MBf Cards (M’sia) Sdn Bhd … RESPONDENTS Coram: Ahmad Maarop FCJ Jeffrey Tan FCJ Abu Samah Nordin FCJ Azahar Mohamed FCJ JUDGMENT OF THE COURT Leave was granted to the Appellant/Defendant (Deutsche) to appeal against the order of the Court of Appeal in respect of the matter decided by the High Court in the exercise of its original jurisdiction, on the following 9 ‘questions of law’: 1 1.1 Whether the principle of law on concluded contracts (generally applied in relation to sale and purchase of property) are applicable in the same manner to financial transactions involving funding by banks or a syndicate of banks. 1.2 Whether the principle in contract law of an enforceable informal contract applies to financing or funding transactions of a complex nature involving banks who are subject to internal credit approval conditions, guidelines and/or limitations. 1.3 Whether it is implicit in every financing transaction involving banks in Malaysia that internal credit approval guidelines as required by the regulating central bank, namely, Bank Negara Malaysia, would automatically apply to the proposed transaction. 1.4 In a setting where documentation (particularly relating to complex financial or funding transactions) is being carried out with the involvement of separately appointed solicitors, whether the principles of ‘locus poenitentiae’ (as applied in other Commonwealth jurisdictions) ought to be considered, namely, that neither party to any apparently alleged concluded contract is bound until and unless such documentation is formally signed-off by both parties. -

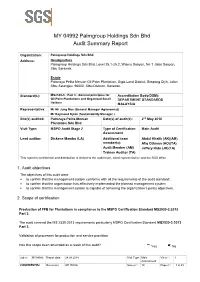

Management System Certification Be: Granted / Continued / Withheld / Suspended Until Satisfactory Corrective Action Is Completed

MY 04992 Palmgroup Holdings Sdn Bhd Audit Summary Report Organization: Palmgroup Holdings Sdn Bhd Address: Headquarters Palmgroup Holdings Sdn Bhd, Level 25.1-25.2, Wisma Sanyan, No 1 Jalan Sanyan, Sibu Sarawak. Estate Palmraya Pelita Meruan Oil Palm Plantation, Gigis Land District, Simpang Dijih, Jalan Sibu-Selangau, 96000, Sibu Division, Sarawak. Standard(s): MS2530-3 : Part 3 : General principles for Accreditation Body(DSM): Oil Palm Plantations and Organized Small DEPARTMENT STANDARDS Holders MALAYSIA Representative: Mr Hii Jung Mee (General Manager Agronomist) Mr Raymond Nyian (Sustainability Manager ) Site(s) audited: Palmraya Pelita Meruan Date(s) of audit(s): 2nd May 2018 Plantation Sdn Bhd Visit Type: MSPO Audit Stage 2 Type of Certification Main Audit Assessment Lead auditor: Dickens Mambu (LA) Additional team Abdul Khalik (AK)(AM) member(s): Afiq Othman (AO)(TA) Audit Member (AM) Jeffery Ridu (JR)(TA) Trainee Auditor (TA) This report is confidential and distribution is limited to the audit team, client representative and the SGS office. 1. Audit objectives The objectives of this audit were: ▪ to confirm that the management system conforms with all the requirements of the audit standard; ▪ to confirm that the organization has effectively implemented the planned management system; ▪ to confirm that the management system is capable of achieving the organization’s policy objectives. 2. Scope of certification Production of FFB for Plantations in compliance to the MSPO Certification Standard MS2530-3:2013 Part 3. The audit covered the MS 2530:2013 requirements particularly MSPO Certification Standard MS2530-3:2013 Part 3. Validation of processes for production and service provision Has this scope been amended as a result of this audit? Yes No Job n°: MY04992 Report date: 24.08.2018 Visit Type: Main Visit n°: 1 Assessment CONFIDENTIAL Document: GP 7003A Issue n°: 10 Page n°: 1 of 23 This is a multi-site audit and an Appendix listing all relevant sites and/or remote Yes No locations has been established (attached) and agreed with the client 3. -

General Sop for Movement Control Order (Mco)

Updated as of 4 February 2021 GENERAL SOP FOR MOVEMENT CONTROL ORDER (MCO) Allowed Activities Operation hours 24 hours Allowed Activity As per rules set in Brief Residents Conditional Hours Description Movement • Essential Services & chains • Purchase / obtain essential ACTIVITIES & PROTOCOLS goods or services Action Brief Description • Obtain health treatment & medicine Involved Areas THE WHOLE OF PENINSULA MALAYSIA, FEDERAL TERRITORY OF LABUAN, SABAH - Please Refer to Sabah • Conducting official State Movement Control Order (MCO) SOP AND SARAWAK (SIBU DIVISION, KAPIT DISTRICT AND SONG DISTRICT) - Please Government and judicial duties Refer to Sibu Division Movement Control Order (MCO) SOP and Kapit District and Song District Movement Control Order (MCO) SOP) Prohibited Activities Enforcement Period 5 February 2021 (starts at 12:01 a.m.) until 18 February 2021 (11:59 p.m.) • Cross district movement within MCO *For Sarawak (Sibu Division) starting from 30 January 2021 (starts at 12.01 am) until 14 February 2021 (11.59pm) areas and crossing state movement *For Sarawak (Kapit District and Song District) starting from 2 February (starts at 12 a.m.) until 15 February 2021 (11:59 p.m.) without the permission of PDRM • Movement in and out of MCO areas Controlled Movement • PDRM is responsible in enforcing control over local infection areas with the assistance of Malaysian Armed Forces, Malaysian without PDRM permission Civil Defense & RELA. The entry and exit routes of MCO areas are closed and controlledby PDRM. • All residents in the MCO areas are NOT ALLOWED to leave their homes / residences except: ➢ Only two (2) household representatives are allowed to go out just to get food supplies, medicine, dietary supplement and Fixed Instructions basic necessities within a radius not exceeding 10 kilometers from their residence or to the nearest place from their residence • Regulation 15 P.U. -

Report on the Trial of Anwar Ibrahim

INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION 124th Assembly and related meetings Panama City (Panama), 15 - 20 April 2011 Governing Council CL/188/13(b)-R.3 Item 13(b) Panama City, 15 April 2011 COMMITTEE ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF PARLIAMENTARIANS f CASE No. MAL/15 - ANWAR IBRAHIM - MALAYSIA THE TRIAL OF ANWAR IBRAHIM Report on the trial of Datuk Seri Anwar bin Ibrahim in the High Court of Malaysia observed on behalf of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) MARK TROWELL QC March 2011 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Datuk Seri Anwar bin Ibrahim (“Anwar Ibrahim”) was in the 1990s the Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia. In 1998 Prime Minister Dato’ Seri Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad dismissed him after he was charged with allegedly sodomizing his wife’s driver and acting corruptly by attempting to interfere with the police investigation. He was convicted and imprisoned after trial, but released when Malaysia’s Federal Court overturned the conviction in September 2004. The Federal Court’s decision was for Anwar Ibrahim the culmination of a six-year struggle for justice after pleading his innocence through the various tiers of the Malaysian court system. During his lengthy period of incarceration, Anwar Ibrahim became the symbol of political opposition to the Mahathir regime. Amnesty International declared him to be a prisoner of conscience, stating that he had been arrested in order to silence him as a political opponent. On 26 August 2008, Anwar Ibrahim won the by-election for the parliamentary seat of Permatang Pauh with a majority of more than 15,000 votes, returning to Parliament as leader of the three-party opposition alliance known as Pakatan Rakyat (PKR).