Podargus Strigoides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus Strigoides)

Bush B Volume 1 u d d i e s Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) When it’s not mistaken for an owl, the Tawny Frogmouth can easily be confused with a tree branch! With narrowed eyelids and a stretched neck, this bark-coloured bird is a master of camouflage. Tawny Frogmouths are between 34cm (females) and 53cm (males) long and can weigh up to 680g. Their plumage is mottled grey, white, black and rufous – the feather patterns help them mimic dead tree branches. Their feathers are soft, like those of owls, allowing for stealthy, silent flight. They have stocky heads with big yellow eyes. Stiff bristles surround their beak; these ‘whiskers’ may help detect the movement of flying insects, and/or protect their faces from the bites or stings of distressed prey (this is not known for certain). Their beak is large and wide, hence the name frogmouth. Their genus name, Podargus, is from the Greek work for gout. Why? Unlike owls they don’t have curved talons on their feet; in fact, their feet are small, and they’re said to walk like a gout-ridden man! Their species name, strigoides, means owl-like. They’re nocturnal and carnivorous, but Tawny Frogmouths aren’t owls – they’re more closely related to Nightjars. There are two other species of frogmouth in Australia – the Papuan Frogmouth (Podargus papuensis) lives in the Cape York Peninsula, and the Marbled Frogmouth (P. ocellatus) is found in two well-separated races: one in tropical rainforests in northern Cape York and the A Tawny Frogmouth disguised against the bark of a tree at Naree in NSW. -

An Initial Estimate of Avian Ark Kinds

Answers Research Journal 6 (2013):409–466. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v6/avian-ark-kinds.pdf An Initial Estimate of Avian Ark Kinds Jean K. Lightner, Liberty University, 1971 University Blvd, Lynchburg, Virginia, 24515. Abstract Creationists recognize that animals were created according to their kinds, but there has been no comprehensive list of what those kinds are. As part of the Answers in Genesis Ark Encounter project, research was initiated in an attempt to more clearly identify and enumerate vertebrate kinds that were SUHVHQWRQWKH$UN,QWKLVSDSHUXVLQJPHWKRGVSUHYLRXVO\GHVFULEHGSXWDWLYHELUGNLQGVDUHLGHQWLÀHG 'XHWRWKHOLPLWHGLQIRUPDWLRQDYDLODEOHDQGWKHIDFWWKDWDYLDQWD[RQRPLFFODVVLÀFDWLRQVVKLIWWKLVVKRXOG be considered only a rough estimate. Keywords: Ark, kinds, created kinds, baraminology, birds Introduction As in mammals and amphibians, the state of avian $VSDUWRIWKH$UN(QFRXQWHUSURMHFW$QVZHUVLQ WD[RQRP\LVLQÁX['HVSLWHWKHLGHDORIQHDWO\QHVWHG Genesis initiated and funded research in an attempt hierarchies in taxonomy, it seems groups of birds to more clearly identify and enumerate the vertebrate are repeatedly “changing nests.” This is partially NLQGVWKDWZHUHSUHVHQWRQWKH$UN,QDQLQLWLDOSDSHU because where an animal is placed depends on which WKH FRQFHSW RI ELEOLFDO NLQGV ZDV GLVFXVVHG DQG D characteristics one chooses to consider. While many strategy to identify them was outlined (Lightner et al. had thought that molecular data would resolve these 6RPHRIWKHNH\SRLQWVDUHQRWHGEHORZ issues, in some cases it has exacerbated them. For this There is tremendous variety seen today in animal HVWLPDWHRIWKHDYLDQ$UNNLQGVWKHWD[RQRPLFVFKHPH OLIHDVFUHDWXUHVKDYHPXOWLSOLHGDQGÀOOHGWKHHDUWK presented online by the International Ornithologists’ since the Flood (Genesis 8:17). In order to identify 8QLRQ ,28 ZDVXVHG *LOODQG'RQVNHUD which modern species are related, being descendants 2012b and 2013). This list includes information on RI D VLQJOH NLQG LQWHUVSHFLÀF K\EULG GDWD LV XWLOL]HG extant and some recently extinct species. -

Evidence for Aviculture: Identifying Research Needs to Advance the Role of Ex Situ Bird Populations in Conservation Initiatives and Collection Planning

Review Evidence for Aviculture: Identifying Research Needs to Advance the Role of Ex Situ Bird Populations in Conservation Initiatives and Collection Planning Paul Rose 1,2 1 Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour, Psychology, University of Exeter, Perry Road, Exeter, Devon EX4 4QG, UK; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 WWT, Slimbridge Wetland Centre, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT, UK Simple Summary: Birds of a whole range of species are housed in zoological collections globally; they are some of the most frequently seen of species in animal populations kept under human care. Research output on birds can provide valuable information on how to advance husbandry and care for particular species, which may further feed into conservation planning. Linking birds housed in human care to those in the wild adds value to these zoo-housed populations; this paper provides areas of research that could be conducted to add value to these zoo-housed birds and suggests increasing the conservation focus and conservation relevance of birds housed by humans. Abstract: Birds are the most speciose of all taxonomic groups currently housed in zoos, but this species diversity is not always matched by their inclusion in research output in the peer-reviewed literature. This large and diverse captive population is an excellent tool for research investigation, the findings of which can be relevant to conservation and population sustainability aims. The One Plan Approach to conservation aims to foster tangible conservation relevance of ex situ populations to those animals living in situ. The use of birds in zoo aviculture as proxies for wild-dwelling Citation: Rose, P. -

Targeted Fauna Assessment.Pdf

APPENDIX H BORR North and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment (Biota, 2019) Bunbury Outer Ring Road Northern and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment Prepared for GHD December 2019 BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna © Biota Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 2020 ABN 49 092 687 119 Level 1, 228 Carr Place Leederville Western Australia 6007 Ph: (08) 9328 1900 Fax: (08) 9328 6138 Project No.: 1463 Prepared by: V. Ford, R. Teale J. Keen, J. King Document Quality Checking History Version: Rev A Peer review: S. Ford Director review: M. Maier Format review: S. Schmidt, M. Maier Approved for issue: M. Maier This document has been prepared to the requirements of the client identified on the cover page and no representation is made to any third party. It may be cited for the purposes of scientific research or other fair use, but it may not be reproduced or distributed to any third party by any physical or electronic means without the express permission of the client for whom it was prepared or Biota Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd. This report has been designed for double-sided printing. Hard copies supplied by Biota are printed on recycled paper. Cube:Current:1463 (BORR North Central Re-survey):Documents:1463 Northern and Central Fauna ARI_Rev0.docx 3 BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna 4 Cube:Current:1463 (BORR North Central Re-survey):Documents:1463 Northern and Central Fauna ARI_Rev0.docx BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 9 1.1 Introduction 9 1.2 Methods -

![1 §4-71-6.5 List of Restricted Animals [ ] Part A: For](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5559/1-%C2%A74-71-6-5-list-of-restricted-animals-part-a-for-2725559.webp)

1 §4-71-6.5 List of Restricted Animals [ ] Part A: For

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS [ ] PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes japonicus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes laevigatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

An Overview of the History, Current Contributions and Future Outlook of Inaturalist in Australia

CSIRO PUBLISHING Wildlife Research, 2021, 48, 289–303 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/WR20154 An overview of the history, current contributions and future outlook of iNaturalist in Australia Thomas Mesaglio A,C and Corey T. Callaghan A,B ACentre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia. BEvolution & Ecology Research Centre, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Citizen science initiatives and the data they produce are increasingly common in ecology, conservation and biodiversity monitoring. Although the quality of citizen science data has historically been questioned, biases can be detected and corrected for, allowing these data to become comparable in quality to professionally collected data. Consequently, citizen science is increasingly being integrated with professional science, allowing the collection of data at unprecedented spatial and temporal scales. iNaturalist is one of the most popular biodiversity citizen science platforms globally, with more than 1.4 million users having contributed over 54 million observations. Australia is the top contributing nation in the southern hemisphere, and in the top four contributing nations globally, with over 1.6 million observations of over 36 000 identified species contributed by almost 27 000 users. Despite the platform’s success, there are few holistic syntheses of contributions to iNaturalist, especially for Australia. Here, we outline the history of iNaturalist from an Australian perspective, and summarise, taxonomically, temporally and spatially, Australian biodiversity data contributed to the platform. -

LCSH Section T

T (Computer program language) T cell growth factor T-Mobile G1 (Smartphone) [QA76.73.T] USE Interleukin-2 USE G1 (Smartphone) BT Programming languages (Electronic T-cell leukemia, Adult T-Mobile Park (Seattle, Wash.) computers) USE Adult T-cell leukemia UF Safe, The (Seattle, Wash.) T (The letter) T-cell leukemia virus I, Human Safeco Field (Seattle, Wash.) [Former BT Alphabet USE HTLV-I (Virus) heading] T-1 (Reading locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell leukemia virus II, Human Safeco Park (Seattle, Wash.) BT Locomotives USE HTLV-II (Virus) The Safe (Seattle, Wash.) T.1 (Torpedo bomber) T-cell leukemia viruses, Human BT Stadiums—Washington (State) USE Sopwith T.1 (Torpedo bomber) USE HTLV (Viruses) t-norms T-6 (Training plane) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell receptor genes USE Triangular norms UF AT-6 (Training plane) BT Genes T One Hundred truck Harvard (Training plane) T cell receptors USE Toyota T100 truck T-6 (Training planes) [Former heading] USE T cells—Receptors T. rex Texan (Training plane) T-cell-replacing factor USE Tyrannosaurus rex BT North American airplanes (Military aircraft) USE Interleukin-5 T-RFLP analysis Training planes T cells USE Terminal restriction fragment length T-6 (Training planes) [QR185.8.T2] polymorphism analysis USE T-6 (Training plane) UF T lymphocytes T. S. Hubbert (Fictitious character) T-18 (Tank) Thymus-dependent cells USE Hubbert, T. S. (Fictitious character) USE MS-1 (Tank) Thymus-dependent lymphocytes T. S. W. Sheridan (Fictitious character) T-18 light tank Thymus-derived cells USE Sheridan, T. S. W. (Fictitious -

Avifaunas of the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains, Indonesian New Guinea

Jared Diamond & K. David Bishop 292 Bull. B.O.C. 2015 135(4) Avifaunas of the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains, Indonesian New Guinea by Jared Diamond & K. David Bishop Received 13 February 2015 Summary.—Of the 11 outlying mountain ranges along New Guinea’s north and north-west coasts, the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains are those most isolated from the Central Range and from other outliers by flat lowlands almost at sea level. The Kumawa Mountains were previously unexplored ornithologically, and the Fakfak Mountains unexplored above 900 m. We report four surveys conducted in 1981, 1983 and 2013. The known combined avifauna is now 283 species, including 77 upland species of which the two ranges share at least 57. Among Central Range upland species whose geographic and altitudinal ranges make them plausible candidates to have colonised Fakfak and Kumawa, 15 are nevertheless unrecorded in both Fakfak and Kumawa. Of those 15, 13 are also unrecorded in the mountains of Yapen Island, which at Pleistocene times of low sea level was also separated from other New Guinea mountains by a wide expanse of flat lowlands. This suggests that colonisation of isolated mountains by those particular upland species depends on dispersal through hilly terrain, and that they do not disperse through flat lowland forest. Because of the low elevation, small area and coastal proximity of the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains, avian altitudinal ranges there show the largest Massenerhebung effect (lowering) of any New Guinea mainland mountains known to us. We compare zoogeographic relations of the Fakfak and Kumawa avifaunas with the mountains of the Vogelkop (the nearest outlier) and with the Central Range. -

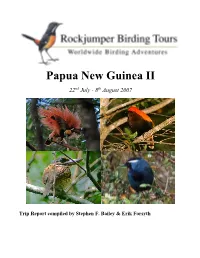

Papua New Guinea II

Papua New Guinea II 22nd July - 8th August 2007 Trip Report compiled by Stephen F. Bailey & Erik Forsyth RBT Papua New Guinea II July 2006 2 Top twelve birds of the trip as voted by the participants 1. Greater Bird-of-paradise 2. Southern Crowned-Pigeon 3. King-of-Saxony Bird-of-paradise 4(tie). King Bird-of-paradise 4(tie). Wallace’s Fairywren 6(tie). Crested Bird-of-paradise 6(tie). Greater Melampitta 8. Palm Cockatoo 9. Crested Berrypecker 10(tie). Brehm’s Tiger-Parrot 10(tie). Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia 10(tie). Blue Bird-of-paradise Tour Summary Our tour of Papua New Guinea began as we boarded our aircraft to the South Pacific islands of the Bismarck Archipelago for the pre-tour extension. First-off, we visited the rainforest of the Pokili Wildlife Management Area which holds the largest breeding colony of Melanesian Scrubfowl in the world. It was an amazing experience to wander through the massive colony of these bizarre birds. We also managed outstanding views of the gorgeous Black-headed Paradise-Kingfisher, Blue-eyed Cockatoo and Red- knobbed Imperial-Pigeon. Some participants were fortunate to spot the rare Black Honey Buzzard. Then we took time to explore several small, remote tropical islands in the Bismarck Sea and were rewarded with sightings of Black-naped Tern, the boldly attractive Beach Kingfisher, Mackinlay’s Cuckoo-Dove and the extraordinary shaggy Nicobar Pigeon. Back on the main island, we visited the Pacific Adventist University, where we found a roosting Papuan Frogmouth, White-headed Shelduck and Comb-crested Jacana. -

A Prolonged Agonistic Interaction Between Two Papuan Frogmouths Podargus Papuensis

Australian Field Ornithology 2017, 34, 26–29 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo34026029 A prolonged agonistic interaction between two Papuan Frogmouths Podargus papuensis C.N. Zdenek1, 2, 3 1Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia QLD 4067, Australia 3Address for correspondence: 15 Murrami Court, Tanah Merah QLD 4128, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract. Papuan Frogmouths Podargus papuensis are large nocturnal birds about which relatively little is known. A prolonged aggressive interaction between two Papuan Frogmouths that involved interlocking beaks was filmed in the Lockhart River region on Cape York Peninsula, Queensland, and is described here. Two additional Papuan Frogmouths were present during the event, one of which gave a call-type (OomWoom) previously unrecorded for this species. Difficulties associated with detecting such agonistic behaviour mean that the prevalence of these contests and their behavioural significance are currently unknown and require further research. Introduction Study area and methods Conflict between conspecifics can be motivated by On 19 August 2015, the observation was recorded at 1856 h territorial dispute, competition for mates, and/or competition in the Lockhart River region on Cape York Peninsula, for resources (West-Eberhard 1983; Begon et al. 2006). Queensland (12°47′S, 143°18′E) (Figure 1). The following Many species have appendages of different forms that equipment was used to film the event: a Canon EOS 5D are used as weapons (e.g. horns, antlers, mandibles) to Mark III camera with a 400-mm (fixed) EF f5.6L IS USM lens secure territories and attract mates (Clutton-Brock & Albon and a directional Rode VideoMic pro external microphone 1979; Kelly 2006), but weaponry is largely absent in birds, (with a windshield; set to 0 dB gain boost). -

BORR Northern and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment (Biota 2019A) – Part 3 (Part 7 of 7) BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna

APPENDIX E BORR Northern and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment (Biota 2019a) – Part 3 (part 7 of 7) BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna 6.0 Conservation Significant Species This section provides an assessment of the likelihood of occurrence of the target species and other conservation significant vertebrate fauna species returned from the desktop review; that is, those species protected by the EPBC Act, BC Act or listed as DBCA Priority species. Appendix 1 details categories of conservation significance recognised under these three frameworks. As detailed in Section 4.2, the assessment of likelihood of occurrence for each species has been made based on availability of suitable habitat, whether it is core or secondary, as well as records of the species during the current or past studies included in the desktop review. Table 6.1 details the likelihood assessment for each conservation significant species. For those species recorded or assessed as having the potential to occur within the study area, further species information is provided in Sections 6.1 and 6.2. 72 Cube:Current:1406a (BORR Alternate Alignments North and Central):Documents:1406a Northern and Central Fauna Rev0.docx BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna This page is intentionally left blank. Cube:Current:1406a (BORR Alternate Alignments North and Central):Documents:1406a Northern and Central Fauna Rev0.docx 73 BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna Table 6.1: Conservation significant fauna returned from the desktop review and their likelihood of occurrence within the study area. ) ) ) 2014 2013 ( ( Marri/Eucalyp Melaleuca 2015 ( Listing ap tus in woodland and M 2012) No. -

Biodiversity-In-Glen-Eira-2018.Pdf

Biosphere Pty Ltd ABN 28 097 295 504 Version 1.1, 7 February 2018 Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................... II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 2 2. THE IMPORTANCE OF NATURE AND BIODIVERSITY ..................... 4 3. THE STUDY APPROACH ........................................................... 5 3.1 Survey of Literature and Pre-existing Information .......... 5 3.2 Fieldwork ....................................................................... 6 4. GLEN EIRA’S VEGETATION PRIOR TO COLONISATION ................. 8 5. WILD PLANT SPECIES ............................................................ 10 5.1 Indigenous Plants ......................................................... 10 5.2 Significant Trees .......................................................... 11 5.3 Non-indigenous Plants.................................................. 12 6. FAUNA AND HABITAT ............................................................. 13 6.1 Fauna Species ............................................................... 13 6.2 Habitat Features ........................................................... 14 7. HOTSPOTS FOR INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ..................... 16 7.1 Sandringham Railway Line Verge, Elsternwick ............ 17 7.2 Rippon Lea Lake and Surrounds ................................... 22 7.3 Caulfield Park .............................................................