Security, Refugee, and Ethnic Minority Policies and Implementation in Vietnam’S Central Highlands, 1968-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfecting Five Christian Character Traits That Empower a Missional Community to Cross-Cultural Mission

Please HONOR the copyright of these documents by not retransmitting or making any additional copies in any form (Except for private personal use). We appreciate your respectful cooperation. ___________________________ Theological Research Exchange Network (TREN) P.O. Box 30183 Portland, Oregon 97294 USA Website: www.tren.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone# 1-800-334-8736 ___________________________ ATTENTION CATALOGING LIBRARIANS TREN ID# Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) MARC Record # Digital Object Identification DOI # Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled PERFECTING FIVE CHRISTIAN CHARACTER TRAITS THAT EMPOWER A MISSIONAL COMMUNITY TO CROSS-CULTURAL MISSION Written by YOUNG KYU KIM and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned reader: _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson Date Received: July 21, 2015 PERFECTING FIVE CHRISTIAN CHARACTER TRAITS THAT EMPOWER A MISSIONAL COMMUNITY TO CROSS-CULTURAL MISSION A FINAL PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY YOUNG KYU KIM JULY 2015 ABSTRACT Perfecting Five Christian Character Traits that Empower a Missional Community to Cross-cultural Mission Young Kyu Kim Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2015 The goal of this study was to explore the relationship between character development and cross-cultural mission. Although restriction and persecution causes limitations, the main challenge of churches in northern Vietnam is not caused by external sources, but the internal state of the Church. -

REDD Programme in Viet Nam (2009-2011)

Assessing the Effective- ness of Training and Awareness Raising Activities of the UN- REDD Programme in Viet Nam (2009-2011) UN-REDD PROGRAMME June 2012 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Mr. Nguyen Quang Tan, Mr. Toon De Bruyn and Ms. Nguyen Thi Thanh Hang, with contributions from Mr. Yurdi Yasmi and Mr. Thomas Enters. The authors would like to thank all who contributed to this assessment. First, thanks to the villagers in Re Teng 2 and Ka la Tongu the team met during the field work. Their hospitality and willingness to share information were invaluable, and without their support, the mission would not have succeeded. The authors are also grateful to the officials at village, commune, and district levels in Lam Ha and Di Linh districts as well as those at the provincial level in Da Lat for facilitating the assessment and patiently responding to the various queries. Important contributions to the assessment were made by trainers, collaborators of the UN-REDD Viet Nam Programme and from government officials at national level. Special thanks also for the staff of the UN-REDD Viet Nam Programme whose logistical and administrative support allowed the mission to proceed smoothly. Finally, thanks to Regional Office of the United Nations Environment Programme and the UN-REDD Programme at regional level for their contributions to the design of the process. Disclaimer The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of RECOFTC – The Center for People and Forests, UN-REDD or any organization linked to the assessment team. Opinions and errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. -

Scaling up Sustainable Robusta Coffee Production in Vietnam: Reducing Carbon Footprints While Improving Farm Profitability

SCALING UP SUSTAINABLE ROBUSTA COFFEE PRODUCTION IN VIETNAM: REDUCING CARBON FOOTPRINTS WHILE IMPROVING FARM PROFITABILITY FULL TECHNICAL REPORT By assignment of USAID Green Invest Asia, JDE and IDH Agri-Logic M. Kuit, D.M. Jansen, N. Tijdink Date: 12 December 2020 Table of contents Executive summary 4 1 Background 6 2 Introduction 7 2.1 Objectives 7 2.2 Research questions 8 2.3 Structure of the report 9 3 Methods 10 3.1 Data sources, harmonisation and data cleaning 10 3.2 Spatial and temporal coverage 10 3.3 Modelling of carbon footprint 15 3.4 Statistical analysis 17 4 Results 18 4.1 Carbon emissions 21 4.2 Carbon stocks and sequestration 34 4.3 Carbon footprint 39 4.4 Carbon footprint and farm profitability 50 4.5 Effectiveness of interventions 56 5 Conclusions 62 5.1 Carbon emissions 62 5.2 Carbon stocks 62 5.3 Carbon footprint 63 5.4 Carbon footprint and profitability 63 5.5 Effectiveness of interventions 63 6 Recommendations 64 6.1 Data 64 6.2 Interventions 66 6.3 Considerations for further research 67 7 References 68 Annex 1: Above Ground Biomass models 69 Annex 2: Summary table of main findings 72 Abbreviations AGB Above Ground Biomass CO2e CO2 equivalent DBH Diameter at Breast Height GBE Green bean equivalent GCP Global Coffee Platform GHG Greenhouse Gas Ha Hectare HDF Highly Diversified Farm ICO International Coffee Organisation K Potassium kWh Kilo Watt Hour MCF Monocrop Farm MDF Medium-diversified Farm Mt Metric ton (1,000 kilogram) N Nitrogen P Phosphorus SCM Supply Chain Management USD US Dollar VND Vietnam Dong DISCLAIMER: This document is produced by PACT Thailand under the USAID Green Invest Asia project and made possible through support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). -

Indigenous Cultures of Southeast Asia: Language, Religion & Sociopolitical Issues

Indigenous Cultures of Southeast Asia: Language, Religion & Sociopolitical Issues Eric Kendrick Georgia Perimeter College Indigenous vs. Minorities • Indigenous groups are minorities • Not all minorities are indigenous . e.g. Chinese in SE Asia Hmong, Hà Giang Province, Northeast Vietnam No Definitive Definition Exists • Historical ties to a particular territory • Cultural distinctiveness from other groups • Vulnerable to exploitation and marginalization by colonizers or dominant ethnic groups • The right to self-Identification Scope • 70+ countries • 300 - 350 million (6%) • 4,000 – 5,000 distinct peoples • Few dozen to several hundred thousand Some significantly exposed to colonizing or expansionary activities Others comparatively isolated from external or modern influence Post-Colonial Developments • Modern society has encroached on territory, diminishing languages & cultures • Many have become assimilated or urbanized Categories • Pastoralists – Herd animals for food, clothing, shelter, trade – Nomadic or Semi-nomadic – Common in Africa • Hunter-Gatherers – Game, fish, birds, insects, fruits – Medicine, stimulants, poison – Common in Amazon • Farmers – Small scale, nothing left for trade – Supplemented with hunting, fishing, gathering – Highlands of South America Commonly-known Examples • Native Americans (Canada – First Nations people) • Inuit (Eskimos) • Native Hawaiians • Maori (New Zealand) • Aborigines (Australia) Indigenous Peoples Southeast Asia Mainland SE Asia (Indochina) • Vietnam – 53 / 10 M (14%) • Cambodia – 24 / 197,000 -

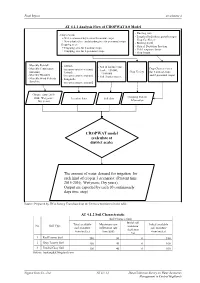

CROPWAT Model (Calculate at District Scale) the Amount of Water Demand

Final Report Attachment 4 AT 4.1.1 Analysis Flow of CROPWAT 8.0 Model - Planting date -Crop season: - Length of individual growth stages + Wet season and dry season for annual crops - Crop Coefficient + New planted tree and standing tree for perennial crops - Rooting depth - Cropping area: - Critical Depletion Fraction + Cropping area for 8 annual crops - Yield response factor + Cropping area for 6 perennial crops - Crop height - Monthly Rainfall - Altitude - Soil & landuse map - Monthly Temperature Crop Characteristics (in representative station) (scale: 1/50.000; (max,min ) Crop Variety (for 8 annual crops - Latitude 1/100.000) - Monthly Humidity and 6 perennial crops) (in representative station) - Soil characteristics. - Monthly Wind Velocity - Longitude - Sunshine (in representative station) Climate data ( 2015- Cropping Pattern 2016; Wet years; Location data Soil data Dry years) Information CROPWAT model (calculate at district scale) The amount of water demand for irrigation for each kind of crop in 3 scenarios: (Present time 2015-2016; Wet years; Dry years). Output are exported by each 10 continuously days time step) Source: Prepared by JICA Survey Team based on the Decrees mentioned in the table. AT 4.1.2 Soil Characteristic Soil Characteristic Initial soil Total available Maximum rain Initial available No Soil Type moisture soil moisture infiltration rate soil moisture depletion (mm/meter) (mm/day) (mm/meter) (%) 1 Red Loamy Soil 180 30 0 180 2 Gray Loamy Soil 160 40 0 160 3 Eroded Gray Soil 100 40 0 100 Source: baotangdat.blogspot.com Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. AT 4.1.1-1 Data Collection Survey on Water Resources Management in Central Highlands Final Report Attachment 4 AT 4.1.3 Soil Type Distribution per District Scale No. -

In Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam Are Revised

E D I N B U R G H J O U R N A L O F B O T A N Y 66 (3): 391–446 (2009) 391 Ó Trustees of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (2009) doi:10.1017/S0960428609990047 AREVISIONOFAESCHYNANTHUS ( GESNERIACEAE)INCAMBODIA, LAOS AND VIETNAM D. J. MIDDLETON The species of Aeschynanthus Jack (Gesneriaceae) in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are revised. Eighteen species are recognised, keys to the species are given, all names are typified, and detailed descriptions of all species are provided. Conservation assessments are given for all species. Aeschynanthus cambodiensis D.J.Middleton, Aeschynanthus jouyi D.J.Middleton and Aeschynanthus pedunculatus D.J.Middleton are newly described. Keywords. Aeschynanthus, Cambodia, Gesneriaceae, Laos, taxonomic revision, Vietnam. Introduction This paper marks the second in a series of geographical revisions of the genus Aeschynanthus Jack (Gesneriaceae) which began with an account of the genus in Thailand (Middleton, 2007b). The previous work also included historical back- ground to the genus and a discussion of the characters. Although it was initially intended that the whole of Aeschynanthus would be monographed region by region, the research has revealed that, due to previously unknown synonymy, there is considerably more overlap in species between areas than was appreciated at the beginning of the project. Therefore, after this publication I now intend to publish the monograph as a complete work at the end and only produce regional revisions, like this one and the Thai revision, where they can feed directly into ongoing Flora projects. Pellegrin (1926, 1930) published two accounts of Aeschynanthus in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WOLFGANG J. LEHMANN Interviewed By

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WOLFGANG J. LEHMANN Interviewed by: Robert Martens Initial interview date: May 9, 1989 Copyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Vietnam 973- 975 Paris Agreements and U.S. presence in Vietnam Hanoi(s 975 offensive Effects of Watergate ,ole of Soviet Union and China .nternational Commission for Control and supervision Economic and political situation in South Vietnam South Vietnamese military Mathias ,esolution 975 .ntervie0 12 Vietnam 973- 975 March 975 Evacuating Plaiku and 3ontum Evacuation planning Evacuating Consulate 4eneral Early April 975 Evacuating Vietnamese employees to 4uam U.S. relations 0ith South Vietnam Evacuations contractors, dependents, 6 nonessential personnel Problems 0ith evacuations Staff performance ,emoving U.S. documents 8ate April 975 Air attack on flight line ,emoving the embassy(s banyan tree ,ocket attack on DAO compound 1 Operation 9Fre:uent Winds; Decision to continue evacuation at night Final evacuation Conclusion The 0arden system Summary of evacuation INTERVIEW : Wolf Lehmann went to Vietnam in June 1973, initially as Consul General in the city of Can Tho, which is located in the Me,ong Delta. He then went to Saigon in March 1974 as Deputy Chief of Mission to Ambassador Graham Martin. For fre1uent periods he was Charg2 d3 Affaires during that 13 months or so prior to the final fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. This period from the time that Mr. Lehmann arrived in Vietnam was one in which support for the war in the 6nited States was declining. We were getting into the beginning of the second Ni8on Administration. -

Wildlife Crime Bulletin Issue I 2020

ISSUE 1 2020 wildlifewildlife crimecrime BULLETIN ALERTS 10 WILDLIFE CRIME ON THE INTERNET 09 ENDING BEAR FARMING 08 ENV’S OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR WILDLIFE PROTECTION 02 Award-winning agencies and individuals at the Outstanding Achievement Award 2019 Nguyen Minh Tien - Kien Giang Environment Police On Dec. 2nd, 2019 ENV hosted the third Outstanding Achievement Awards for Wildlife Protection to recognize the class-setting work of Vietnam’s law enforcement agencies and legal system in curtailing wildlife crime and protecting Vietnam’s precious biodiversity. Among those honored at the event judges, prosecutors, and procuracies. The awards ceremony recognized the crucial role these agencies and individuals play, not only in applying the law, but in creating proper deterrents for protential wildlife Luu Phuoc Nguyen - Quang Nam Environment Police criminals. The categories and winners: for professionals in law enforcement agencies that directly handled cases involving the enforcement of wildlife protection laws and regulations. Winners (two awards): Nguyen Minh Tien - Kien Giang Environment Police and Luu Phuoc Nguyen - Quang Nam Environment Police Outstanding Judge Award for a judge who issued verdict(s) shown to positively impact the judiciary system and strengthen the protection of wildlife. Winner: Ngo Duc Thu - Tan Binh District Court Outstanding Judge Award Ngo Duc Thu – Tan Binh District Court 2 ENV Wildlife Crime Bulletin - Issue No.1/2020 Outstanding Prosecutor Award for a prosecutor positively impact the judiciary system and strengthen the protection of wildlife. Outstanding Prosecutor Award Winner: Hua Ngoc Thong - Dien Bien Town Hua Ngoc Thong – Dien Bien Town Procuracy Procuracy Outstanding Agency Award for government agencies (including courts, procuracies, police departments, Forest Protection Departments, Customs or Fisheries Departments) have substantially contributed to the strengthening of wildlife protection in Vietnam. -

The Language Olicy of Minority Languages in Vietnam

특집 ••• 사라져 가는 언어들 The language olicy of minority languages in Vietnam LY Toan Thang․Instituteof Linguistics,Hanoi-Vietnam 0. Introduction The most important ethno-linguistic feature of Vietnam is that during about four thousands years, throughout the very long historical period of foundation, protection and development of the country, the ethnic groups in Vietnam were living side by side in peaceful harmony and unity, without any ethno-linguistic war between the Viet and minorities, or between the minorities themselves. In this ethno-linguistic aspect the history of Vietnam is the history of interaction of languages following the tendency of convergence and intergration for forming an ethno-linguistic union in Vietnam. That tendency is strengthened in new historical, political, economic and socio-cultural conditions of Vietnam in XX century. Vietnam is a multiethnic, multicultural and multilingual country comprising 54 ethnic groups(ethnicities): 01 majority the Viet(the 특집 ․ 사라져 가는 언어들 ․ 51 Kinh) and 53 minorities, but about 100 minority languages/dialects. A couple of ethno-linguistic communities, such as the Hoa(Chinese) and the Khmer, have alinguistic relationship with China and Cambodge, in which countries Chinese and Khmer are the national languages. The Tay, Nung and Thai have genetic relations with the Choang(Zhung), Thai, Shan in South China, Laos, Thailand and Burma. The Hmong are about 550 thousands in Vietnam, a few millions in China, a few thousands in Thailand and Laos, and even a few hundreds of thousands Hmong people in USA, Australia and France. Since independence in 1945 the language policy in Vietnam has reflected a strategy of preservation, promotion and development of spoken and written languages, including both Vietnamese and minority languages. -

List of Districts of Vietnam

S.No Province Name of District 1 An Giang Province An Phú 2 An Giang Province Châu Đốc 3 An Giang Province Châu Phú 4 An Giang Province Châu Thành 5 An Giang Province Chợ Mới 6 An Giang Province Long Xuyên 7 An Giang Province Phú Tân 8 An Giang Province Tân Châu 9 An Giang Province Thoại Sơn 10 An Giang Province Tịnh Biên 11 An Giang Province Tri Tôn 12 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Bà Rịa 13 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Châu Đức 14 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Côn Đảo 15 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Đất Đỏ 16 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Long Điền 17 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Tân Thành 18 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Vũng Tàu 19 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Xuyên Mộc 20 Bắc Giang Province Bắc Giang 21 Bắc Giang Province Hiệp Hòa 22 Bắc Giang Province Lạng Giang 23 Bắc Giang Province Lục Nam 24 Bắc Giang Province Lục Ngạn 25 Bắc Giang Province Sơn Động 26 Bắc Giang Province Tân Yên 27 Bắc Giang Province Việt Yên 28 Bắc Giang Province Yên Dũng 29 Bắc Giang Province Yên Thế 30 Bắc Kạn Province Ba Bể 31 Bắc Kạn Province Bắc Kạn 32 Bắc Kạn Province Bạch Thông 33 Bắc Kạn Province Chợ Đồn 34 Bắc Kạn Province Chợ Mới 35 Bắc Kạn Province Na Rì 36 Bắc Kạn Province Ngân Sơn 37 Bắc Kạn Province Pác Nặm 38 Bạc Liêu Province Bạc Liêu 39 Bạc Liêu Province Đông Hải 40 Bạc Liêu Province Giá Rai 41 Bạc Liêu Province Hòa Bình 42 Bạc Liêu Province Hồng Dân 43 Bạc Liêu Province Phước Long 44 Bạc Liêu Province Vĩnh Lợi 45 Bắc Ninh Province Bắc Ninh 46 Bắc Ninh Province Gia Bình www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Bắc Ninh Province Lương Tài 48 Bắc Ninh Province Quế Võ 49 Bắc Ninh Province Thuận -

Review on the Taxonomy, Biology, Ecology, and the Status, Trend and Population Structure and Dynamics of Dalbergia Oliveri in Vietnam

REVIEW ON THE TAXONOMY, BIOLOGY, ECOLOGY, AND THE STATUS, TREND AND POPULATION STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS OF DALBERGIA OLIVERI IN VIETNAM Nguyen Tien Hiep1, Nguyen Manh Ha2 & La Quang Trung3 1 Nguyen Tien Hiep, Center for Plant Conservation, VUSTA, No. 25/32/89 Lac Long Quan street, Ha Noi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Nguyen Manh Ha, CITES Management Authority of Vietnam. MARD, No. 2 Ngoc Ha street, Ha Noi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected]. 3 La Quang Trung, Center for Nature Conservation and Development, No. 5/165 Duong nuoc Phan Lan, Tu Lien ward, Tay Ho district, Ha Noi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected]. Ha Noi, December 2019 Project title: Strengthening the management and conservation of Dalbergia cochinchinensis and Dalbergia oliveri in Vietnam. Programme: CITES Tree Species Programme Project funding: European Union support to CITES Secretariat Implementing Center for Nature Conservation and Development partner: Cover Dalbergia oliveri in Cat Tien national park illustration: Photo: La Quang Trung/CCD – 2019. Citation: Nguyen Tien Hiep, Nguyen Manh Ha & La Quang Trung (2019). Review on the taxonomy, biology, ecology, and the status, trend and population structure and dynamics of Dalbergia oliveri in Vietnam. Center for Nature Conservation and Development, Ha Noi, Vietnam. Copyright: Center for Nature Conservation and Development No. 5 Lane165, Duong Nuoc Phan Lan, Tu Lien Ward, Tay Ho District, Ha Noi, Vietnam. Tel: +84 (0) 246 682 0486 Email: [email protected] 2 Acknowledgement The report “Review on the taxonomy, biology, ecology, and the status, trend and population structure and dynamics of Dalbergia oliveri in Vietnam” was compiled based on the requirements of the CITES Management Authority of Vietnam and the Center for Nature conservation and Development through the project “Strengthening the management and conservation of Dalbergia cochinchinensis and Dalbergia oliveri in Vietnam”. -

From Ethnocide to Ethnodevelopment? Ethnic Minorities and Indigenous Peoples in Southeast Asia

Third World Quarterly, Vol 22, No 3, pp 413–4 36, 2001 From ethnocide to ethnodevelopment? Ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia GERARD CLARKE ABSTRACT This paper examines the impact of development, including the impact of government and donor programmes, on ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia. Through an examination of government policy, it considers arguments that mainstream development strategies tend to generate conflicts between states and ethnic minorities and that such strategies are, at times, ethnocidal in their destructive effects on the latter. In looking at more recent government policy in the region, it considers the concept of ethno- development (ie development policies that are sensitive to the needs of ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples and where possible controlled by them), and assesses the extent to which such a pattern of development is emerging in the region. Since the late 1980s, it argues, governments across the region have made greater efforts to acknowledge the distinct identities of both ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples, while donors have begun to fund projects to address their needs. In many cases, these initiatives have brought tangible benefits to the groups concerned. Yet in other respects progress to date has been modest and ethnodevelopment, the paper argues, remains confined to a limited number of initiatives in the context of a broader pattern of disadvantage and domination. Ama Puk is a prosperous coffee farmer in Vietnam’s Dak Lak province. A member of the Ede (E De) minority, Ama lived in perennial poverty as a subsis- tence rice producer until the establishment of the state-run Ea Tul Coffee Company in 1985.