Sondheim, Stephen (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music, Dance and Theatre (MDT) 1

Music, Dance and Theatre (MDT) 1 MDT 510 Latin American Music (3 Credits) MUSIC, DANCE AND THEATRE A course in the music of selected Latin America countries offering music and Spanish-language majors and educators perspectives into the (MDT) musical traditions of this multifaceted region. Analysis of the music will be discussed in terms that accommodate non specialists, and all lyrics MDT 500 Louis Armstrong-American Hero (3 Credits) will be supplied with English translations. A study of the development of jazz with Louis Armstrong as the vehicle: MDT 511 Vocal Pedagogy (3 Credits) who he influenced and how he did it. Comparative analytical studies with This course is to provide the student of singing a deeper understanding his peers and other musicians are explored. of the vocal process, physiology, and synergistic nature of the vocal MDT 501 Baroque Music (3 Credits) mechanism. We will explore the anatomical construction of the voice as This course offers a study of 17th and 18th century music with particular well as its function in order to enlighten the performer, pedagogue and emphasis on the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Dietrich Buxtehude, scholar. Each student will learn to codify a practical knowledge of, and Arcangelo Corelli, Francois Couperin, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, skill in, teaching voice. George Frederick Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Claudio Monteverdi, Jean- MDT 520 Musical On B'Way&Hollywood I (3 Credits) Philippe Rameau, Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Gerog Telemann, This course offers an analysis of current Broadway musicals with special and Antonio Vivaldi. seminars with those connected with one or two productions. -

A Quantitative Analysis of the Songs of Cole Porter and Irving Berlin

i DEVELOPMENT OF CREATIVE EXPERTISE IN MUSIC: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SONGS OF COLE PORTER AND IRVING BERLIN A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard W. Hass January, 2009 ii ABSTRACT Previous studies of musical creativity lacked strong foundations in music theory and music analysis. The goal of the current project was to merge the study of music perception and cognition with the study of expertise-based musical creativity. Three hypotheses about the nature of creativity were tested. According to the productive-thinking hypothesis, creativity represents a complete break from past knowledge. According to the reproductive-thinking hypothesis, creators develop a core collection of kernel ideas early in their careers and continually recombine those ideas in novel ways. According to what can be called the field hypothesis, creativity involves more than just the individual creator; creativity represents an interaction between the individual creator, the domain in which the creator works, and the field, or collection of institutions that evaluate creative products. In order to evaluate each hypothesis, the musical components of a sample of songs by two eminent 20 th century American songwriters, Cole Porter and Irving Berlin, were analyzed. Five separate analyses were constructed to examine changes in the psychologically salient musical components of Berlin’s and Porter’s songs over time. In addition, comparisons between hit songs and non-hit songs were also drawn to investigate whether the composers learned from their cumulative songwriting experiences. Several developmental trends were found in the careers of both composers; however, there were few differences between hit songs and non-hit songs on all measures. -

KEVIN COLE “America's Pianist” Kevin Cole Has Delighted

KEVIN COLE “America’s Pianist” Kevin Cole has delighted audiences with a repertoire that includes the best of American Music. Cole’s performances have prompted accolades from some of the foremost critics in America. "A piano genius...he reveals an understanding of harmony, rhythmic complexity and pure show-biz virtuosity that would have had Vladimir Horowitz smiling with envy," wrote critic Andrew Patner. On Cole’s affinity for Gershwin: “When Cole sits down at the piano, you would swear Gershwin himself was at work… Cole stands as the best Gershwin pianist in America today,” Howard Reich, arts critic for the Chicago Tribune. Engagements for Cole include: sold-out performances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl; BBC Concert Orchestra at Royal Albert Hall; National Symphony at the Kennedy Center; Hong Kong Philharmonic; San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra (London); Boston Philharmonic, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (Australia) Minnesota Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Seattle Symphony,Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra; New Zealand Symphony, Edmonton Symphony (Canada), Ravinia Festival, Wolf Trap, Savannah Music Festival, Castleton Festival, Chautauqua Institute and many others. He made his Carnegie Hall debut with the Albany Symphony in May 2013. He has shared the concert stage with, William Warfield, Sylvia McNair, Lorin Maazel, Brian d’Arcy James, Barbara Cook, Robert Klein, Lucie Arnaz, Maria Friedman, Idina Menzel and friend and mentor Marvin Hamlisch. Kevin was featured soloist for the PBS special, Gershwin at One Symphony Place with the Nashville Symphony. He has written, directed, co- produced and performed multimedia concerts for: The Gershwin’s HERE TO STAY -The Gershwin Experience, PLAY IT AGAIN, MARVIN!-A Celebration of the music of Marvin Hamlisch with Pittsburgh Symphony and Chicago Symphony and YOU’RE THE TOP!-Cole Porter’s 125th Birthday Celebration and I LOVE TO RHYME – An Ira Gershwin Tribute for the Ravinia Festival with Chicago Symphony. -

Cal-Western Region Regional Categories Finals Concert

Cal-Western Region Regional Categories Finals Concert A. Childrens Classical Bella Leybovich Wie Melodien zieht es mir Johannes Brahms Isabella Xiong High Green Mountain Ruth Morris Gray Marla Jones, pianist (Gao Shan Qing) Savannah Springer Valenciana arr. Christine Donkin Jenn Crandall, pianist B. Childrens Music Theater Brooklyn Martin Waiting For Life Stephen Flaherty McKenzie Lopezlira Middle Of A Moment Benj Pasek & Justin Paul Bella Leybovich The Tree William Friedman & Will Holt C. Youth Classical Sydney Sublette Se tu m'ami, se sospri Giovanni Pergolesi HyeJung Shin, pianist Wesley Geary Cangio d'aspetto G. F. Handel Marie Sierra, pianist Baylee Horvath Heigh-ho the Sunshine Montague F. Phillips Jenn Crandall, pianist D1. Youth MT 11-12 Year Olds Evan Vance The Kite Clark Gesner Stephen Shermitzler, pianist Maddie Miller Everlasting Chris Miller & Nathan Tysen Baylee Horvath Good Morning Nacio Brown Jenn Crandall, pianist Hadley Fugate Amazing Maizie Lynn Ahrens & Stephen Flaherty Cal-Western Region Regional Categories Finals Concert P. 2 D2. Youth MT 13-14 Year Olds Sky Keyoung Pulled Andrew Lippa Wesley Geary Try Me Jerry Bock Shreya Ghoshal In My Own Little Corner Richard Rodgers E. Youth CCM Baylee Horvath First Lauren Diagle Jenn Crandall, pianist Bella Leybovich Better Place Rachel Platten & Sally Seltman Hadley Fugate Hallelujah Leonard Cohen F1. HS CCM Treble 14-16 Year Olds Kayla Venger Misty Erroll Garner Kyle Blair, pianist Makenna Jacobs There's a Place for Us Carrie Underwood Jenn Crandall, pianist Zoie Moller Brand New Key Melanie Safka Melissa McGuire, pianist F2. High School CCM 17-18 Year Olds Isabella Brown This Thing Called Living Eloïse (TTCL) Kylie Merrill Piece by Piece Kelly Clarkson & Greg Kurstin Karen Rowley Better on My Own Karen Rowley Cal-Western Region Regional Categories Finals Concert P. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea. 80200, Spring 2002 David Savran, CUNY Feb 4—Introduction: One Singular Sensation To be read early in the semester: DiMaggio, “Cultural Boundaries and Structural Change: The Extension of the High Culture Model to Theater, Opera, and the Dance, 1900-1940;” Block, “The Broadway Canon from Show Boat to West Side Story and the European Operatic Ideal;” Savran, “Middlebrow Anxiety” 11—Kern, Hammerstein, Ferber, Show Boat Mast, “The Tin-Pan-Tithesis of Melody: American Song, American Sound,” “When E’er a Cloud Appears in the Blue,” Can’t Help Singin’; Berlant, “Pax Americana: The Case of Show Boat;” 18—No class 20—G. and I. Gershwin, Bolton, McGowan, Girl Crazy; Rodgers, Hart, Babes in Arms ***Andrea Most class visit*** Most, Chapters 1, 2, and 3 of her manuscript, “We Know We Belong to the Land”: Jews and the American Musical Theatre; Rogin, Chapter 1, “Uncle Sammy and My Mammy” and Chapter 2, “Two Declarations of Independence: The Contaminated Origins of American National Culture,” in Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot; Melnick, “Blackface Jews,” from A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song 25— G. and I. Gershwin, Kaufman, Ryskind, Of Thee I Sing, Shall We Dance Furia, “‘S’Wonderful: Ira Gershwin,” in his Poets of Tin Pan Alley, Mast, “Pounding on Tin: George and Ira Gershwin;” Roost, “Of Thee I Sing” Mar 4—Porter, Anything Goes, Kiss Me, Kate Furia, “The Tinpantithesis of Poetry: Cole Porter;” Mast, “Do Do That Voodoo That You Do So Well: Cole Porter;” Lawson-Peebles, “Brush Up Your Shakespeare: The Case of Kiss Me Kate,” 11—Rodgers, Hart, Abbott, On Your Toes; Duke, Gershwin, Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 Furia, “Funny Valentine: Lorenz Hart;” Mast, “It Feels Like Neuritis But Nevertheless It’s Love: Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart;” Furia, Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist, pages 125-33 18—Berkeley, Gold Diggers of 1933; Minnelli, The Band Wagon Altman, The American Film Musical, Chaps. -

The Wicker Husband Education Pack

EDUCATION PACK 1 1 Contents Introduction Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: The Watermill’s Production of The Wicker Husband ........................................................................ 4 A Brief Synopsis.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Character Profiles…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....…8 Note from the Writer…………………………………………..………………………..…….……………………………..…………….10 Interview with the Director ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..………….. 13 Section 2: Behind the Scenes of The Watermill’s The Wicker Husband …………………………………..… ...... 15 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................................................................... 16 An Interview with The Musical Director .................................................................................................................. .20 The Design Process ......................................................................................................................................................... 21 The Wicker Husband Costume Design ...................................................................................................................... 23 Be a Costume Designer……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..25 -

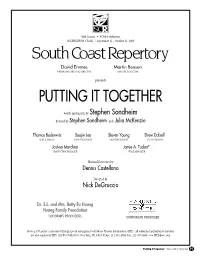

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Cole Porter Lesson Plan

COLE PORTER Gay U.S. Composer (1893-1964) Cole Porter remains one of America's all-time greatest composers and songwriters – one of the few who wrote both the lyrics and the music. His hits include the musical comedies The Gay Divorce (1932), Anything Goes (1934), Panama Hattie (1939), Kiss Me, Kate (1948) and Can-Can (1952); and featured songs like "Night and Day", "I Get a Kick out of You", "I've Got You Under My Skin" and “Begin the Beguine.” He worked with legendary stars Fred Astaire, Ethel Merman, Fanny Brice, Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Roy Rogers, Bing Crosby, Mary Martin and the Andrews Sisters; and is considered one of the principal contributors to The Great American Songbook. He married his close friend, socialite Linda Lee Thomas, in 1919 – a union that assured her social status while increasing his chances for success in his career. They lived a happy, publicly acceptable life, but Porter’s reputation as a regular fixture at some of underground Hollywood’s most notorious gay gatherings led to hushed rumors within upper-crust circles that threatened Thomas’s social standing. They separated in the early 1930s (but did not divorce) and remained close friends. In 1937 Porter was crippled when his legs were crushed in a riding accident. He was in the hospital for months, struggling against mental and physical decline, though he continued to write with some success for the next several years. But the death of his beloved mother in 1952, followed by his wife’s passing in 1954, and the amputation of his right leg in 1958, took its toll. -

Ouachita Students Myers and Walls to Perform Sophomore Recitals Oct

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Press Releases Office of Communication 10-19-2016 Ouachita students Myers and Walls to perform sophomore recitals Oct. 28 Ouachita News Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/press_releases Part of the Higher Education Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons For immediate release Ouachita students Myers and Walls to perform sophomore recitals Oct. 28 By OBU News Bureau October 19, 2016 For more information, contact OBU’s news bureau at [email protected] or (870) 245-5208. ARKADELPHIA, Ark. — Ouachita Baptist University will host Zachary Myers and Cody Walls for their sophomore musical theatre recitals on Friday, Oct. 28, at 11 a.m. in McBeth Recital Hall. The recitals are free and open to the public. Myers, from Greenwood, Ark., and Walls, from Fort Smith, Ark., both are musical theatre majors. They are students of Dr. Glenda Secrest, professor of music, and Drew Hampton, assistant professor of theatre arts. Phyllis Walker, OBU staff accompanist, will provide piano accompaniment for both performances. Walls will open his recital with Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim’s “All I Need Is the Girl” from Gypsy, followed by “What You Mean to Me” from Finding Neverland by Eliot Kennedy, David Lindsay- Abaire’s Rabbit Hole and “Caught in the Storm” by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul. Lisa Lambert and Greg Morrison’s “I Am Aldolpho” from The Drowsy Chaperone will close his recital. Mackenzie Osborne, a sophomore musical theatre major from Heath, Texas, helped choreograph the recital and will perform with Walls during a portion of the performance. -

The Great American Songbook in the Classical Voice Studio

THE GREAT AMERICAN SONGBOOK IN THE CLASSICAL VOICE STUDIO BY KATHERINE POLIT Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Patricia Wise, Research Director and Chair __________________________________ Gary Arvin __________________________________ Raymond Fellman __________________________________ Marietta Simpson ii For My Grandmothers, Patricia Phillips and Leah Polit iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the members of my committee—Professor Patricia Wise, Professor Gary Arvin, Professor Marietta Simpson and Professor Raymond Fellman—whose time and help on this project has been invaluable. I would like to especially thank Professor Wise for guiding me through my education at Indiana University. I am honored to have her as a teacher, mentor and friend. I am also grateful to Professor Arvin for helping me in variety of roles. He has been an exemplary vocal coach and mentor throughout my studies. I would like to give special thanks to Mary Ann Hart, who stepped in to help throughout my qualifying examinations, as well as Dr. Ayana Smith, who served as my minor field advisor. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their love and support throughout my many degrees. Your unwavering encouragement is the reason I have been -

Hugh Panaro Is Perhaps Best Known for Having Played the Coveted Role

Hugh Panaro is perhaps best known for having played the coveted role of the Phantom in Broadway's The Phantom of the Opera over 2,000 times, including the 25th Anniversary production. In fact, Hugh is one of the few actors to be cast by Harold Prince as both The Phantom and Raoul in the show's Broadway production. Hugh made his Broadway debut in the original production of Les Misérables as Marius, the role he originated in the First National Company. He also created the roles of Buddy in the original Side Show (Sony cast recording); Julian Craster in Jule Styne's last musical, The Red Shoes; and the title role in the American premiere of Cameron Mackintosh's Martin Guerre. Hugh was nominated for an Outer Critics Circle Award for his performance in the title role of Elton John's Lestat, based on Anne Rice's Vampire Chronicles. He made his West End debut in the original London company of Harold Prince's Show Boat as Gaylord Ravenal, the role he previously played in the Broadway and Toronto productions. At the prestigious 5th Avenue Theater in Seattle, Hugh played George Seurat in Sam Buntrock's Tony Award-winning production of Sunday in the Park with George, and Robert in Stephen Sondheim's Company. Hugh's performance as Jean Valjean in the Walnut Street Theater's production of Les Misérables earned him the prestigious Barrymore Award, for which he was again nominated after a turn as Fagin in Oliver! In 2012, Hugh was honored with the Edwin Forrest Award for his long-term contribution to the theater.