The Role of Community Health Workers (Chws) in Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Chhattisgarh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Industrial Profile of Kanker District

lR;eso t;rs Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Kanker District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute, Raipur (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone :- 0771- 2427719 /2422312 Fax: 0771 - 2422312 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmediraipur.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 1 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 1 1.2 Topography 1 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 1 1.4 Forest 2 1.5 Administrative set up 2 2. District at a glance 3 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Kanker 6 3. Industrial Scenario Of Kanker 6 3.1 Industry at a Glance 6 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 7 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 8 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 8 3.5 Major Exportable Item 8 3.6 Growth Trend 8 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 8 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 9 3.8.1 List of the units in Kanker & near by Area 9 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 9 3.9 Service Enterprises 9 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 9 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 9 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 10 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 10 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 10 4.1.2 Service Sector 10 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 10 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 10 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 13 Brief Industrial Profile of Kanker District 1. -

Statistical Report General Election, 1998 The

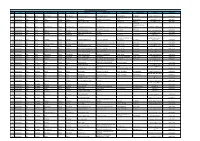

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1998 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MADHYA PRADESH ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – State Elections, 1998 Legislative Assembly of Madhya Pradesh STATISCAL REPORT ( National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 2 2. Other Abbreviations And Description 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 12 5. Performance of Political Parties 13 - 14 6. Candidate Data Summary 15 7. Electors Data Summary 16 8. Women Candidates 17 - 25 9. Constituency Data Summary 26 - 345 10. Detailed Results 346 - 413 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 1998 to the Legislative Assembly of MADHYA PRADESH LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . JD Janata Dal (Not to be used in General Elections, 1999) 7 . SAP Samata Party STATE PARTIES 8 . ICS Indian Congress (Socialist) 9 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 10 . JP Janata Party 11 . LS Lok Shakti 12 . RJD Rashtriya Janata Dal 13 . RPI Republican Party of India 14 . SHS Shivsena 15 . SJP(R) Samajwadi Janata Party (Rashtriya) 16 . SP Samajwadi Party REGISTERED(Unrecognised ) PARTIES 17 . ABHM Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha 18 . ABJS Akhil Bharatiya Jan Sangh 19 . ABLTC Akhil Bhartiya Lok Tantrik Congress 20 . ABMSD Akhil Bartiya Manav Seva Dal 21 . AD Apna Dal 22 . AJBP Ajeya Bharat Party 23 . BKD(J) Bahujan Kranti Dal (Jai) 24 . -

Common Service Center List

CSC Profile Details Report as on 15-07-2015 SNo CSC ID District Name Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 E-mail Id Contact No 1 CG010100101 Durg Balod Karahibhadar 491227 Karahibhadar LALIT KUMAR SAHU vill post Karahibhadar block dist balod chhattisgarh [email protected] 8827309989 VILL & POST : NIPANI ,TAH : 2 CG010100102 Durg Balod Nipani 491227 Nipani MURLIDHAR C/O RAHUL COMUNICATION BALOD DISTRICT BALOD [email protected] 9424137413 3 CG010100103 Durg Balod Baghmara 491226 Baghmara KESHAL KUMAR SAHU Baghmara BLOCK-BALOD DURG C.G. [email protected] 9406116499 VILL & POST : JAGANNATHPUR ,TAH : 4 CG010100105 Durg Balod JAGANNATHPUR 491226 JAGANNATHPUR HEMANT KUMAR THAKUR JAGANNATHPUR C/O NIKHIL COMPUTER BALOD [email protected] 9479051538 5 CG010100106 Durg Balod Jhalmala 491226 Jhalmala SMT PRITI DESHMUKH VILL & POST : JHALMALA TAH : BALOD DIST:BALOD [email protected] 9406208255 6 CG010100107 Durg Balod LATABOD LATABOD DEKESHWAR PRASAD SAHU LATABOD [email protected] 9301172853 7 CG010100108 Durg Balod Piparchhedi 491226 PIPERCHEDI REKHA SAO Piparchhedi Block: Balod District:Balod [email protected] 9907125793 VILL & POST : JAGANNATHPUR JAGANNATHPUR.CSC@AISEC 8 CG010100109 Durg Balod SANKARAJ 491226 SANKARAJ HEMANT KUMAR THAKUR C/O NIKHIL COMPUTER ,TAH : BALOD DIST: BALOD TCSC.COM 9893483408 9 CG010100110 Durg Balod Bhediya Nawagaon 491226 Bhediya Nawagaon HULSI SAHU VILL & POST : BHEDIYA NAWAGAON BLOCK : BALOD DIST:BALOD [email protected] 9179037807 10 CG010100111 -

Madhya Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2000 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Part I Preliminary Sections 1

THE MADHYA PRADESH REORGANISATION ACT, 2000 _____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS _____________ PART I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II REORGANISATION OF THE STATE OF MADHYA PRADESH 3. Formation of Chhattisgarh State. 4. State of Madhya Pradesh and territorial divisions thereof. 5. Amendment of the First Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Saving powers of the State Government. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES The Council of States 7. Amendment of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 8. Allocation of sitting members. The House of the People 9. Representation in the House of the People. 10. Delimitation of Parliamentary and Assembly constituencies. 11. Provision as to sitting members. The Legislative Assembly 12. Provisions as to Legislative Assemblies. 13. Allocation of sitting members. 14. Duration of Legislative Assemblies. 15. Speakers and Deputy Speakers. 16. Rules of procedure. Delimitation of constituencies 17. Delimitation of constituencies. 18. Power of the Election Commission to maintain Delimitation Orders up-to-date. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 19. Amendment of the Scheduled Castes Order. 20. Amendment of the Scheduled Tribes Order. PART IV HIGH COURT 21. High Court of Chhattisgarh. 22. Judges of Chhattisgarh High Court. 23. Jurisdiction of Chhattisgarh High Court. 24. Special provision relating to Bar Council and advocates. 25. Practice and procedure in Chhattisgarh High Court. 26. Custody of seal of Chhattisgarh High Court. 27. Form of writs and other processes. 28. Powers of Judges. 1 SECTIONS 29. Procedure as to appeals to Supreme Court. 30. Transfer of proceedings from Madhya Pradesh High Court to Chhattisgarh High Court. 31. Right to appear or to act in proceedings transferred to Chhattisgarh High Court. -

8`Ge @<¶D 423 Dved Derxv W`C WRTV

RNI Regn. No. CHHENG/2012/42718, Postal Reg. No. - RYP DN/34/2013-2015 *+"#*$,- %'"/ 84&-4+585+509 6+/ +&85/4+5+ 56(6470 -(&6-(4-&05+ &8 850&80&0 8&0(8&48 (&0&8( /8 0&0:&056858 8565/-&07+ 5(8&40 (958&-&<.&9 && '5, **6 $ ;& +% 5 &"'" . / !.012304 ! "#$!%&' $$() ''( *# R )) 05 56( city, 4,000 hot spots will be installed at bus stands. The he Aam Aadmi Party remaining 7,000 hot spots will T(AAP) Government-led by be installed across the market- Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal places and Residents’ Welfare on Wednesday announced the Associations (RWAs) in Delhi, Wi-Fi scheme under which a with each constituency having person will get free 15 GB data 100 hot spots. per month through a hot spot As per the officials, the network across the national work order for the installation Capital from December 16. of the 100 free Wi-Fi connec- With this announcement, tions has been awarded and the Kejriwal asserted his party has installation is under process. fulfilled all its poll promises. “The total expenditure of the 05 56( He said 100 hot spots will installation scheme will be be inaugurated in the first around 100 crore. The scheme he stage is set for a bitter phase at bus stands and parks will operate as per a standard Tconfrontation between the coming under the Samaypur rent model — the Delhi Opposition and the Treasury Badli and Adarsh Nagar Government will pay rent every Benches in Parliament next Assembly constituency on month to the week when the Government December 16. -

![Chhattisgarh Sanchar Kranti Yojana [CG SKY] Phase 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3524/chhattisgarh-sanchar-kranti-yojana-cg-sky-phase-1-3983524.webp)

Chhattisgarh Sanchar Kranti Yojana [CG SKY] Phase 1

Detailed Project Report (DPR) for implementation of Chhattisgarh Sanchar Kranti Yojana [CG SKY] Phase 1 Reaping the benefits of bringing people into the mainstream Prepared By Chhattisgarh Infotech & Biotech Promotion Society (CHiPS) 0 DPR for Implementation of “Chhattisgarh Sanchar Kranti Yojana [CG SKY] Phase 1” Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 2. Project Background ........................................................................................................................ 4 3. Main Objectives of the Chhattisgarh Sanchar Kranti Yojana ........................................................ 7 4. Project Overview ............................................................................................................................ 7 4.1 Project Vision .......................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 Beneficiaries ............................................................................................................................ 7 4.3 Key stakeholders ..................................................................................................................... 8 4.4 Governance Structure ............................................................................................................. 9 4.5 Project monitoring ................................................................................................................. -

Expansion of Iron Ore Mining Lease Area from 106.60 Ha. to 138.96 Ha

Expansion of Iron Ore Mining Lease Area from 106.60 ha. to 138.96 ha. at Village: Kachhe, Tehsil: Bhanupratappur, District: Uttar Bastar (Kanker), Chhattisgarh Pre -Feasibility R eport PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT EXCUTIVE SUMMARY Project : Mining Lease of Iron Ore (Ari Dongri Iron Ore Mine) Name of Company / Mine Owner : Godawari Power and Ispat Limited Location Village : Kachhe Tehsil : Bhanupratappur District : Uttar Baster (Kanker) State : Chhattisgarh 1 Mining Lease Area & Type of Land 32.36 (Government Forest Land) 2 Geographical co-ordinates Latitude Longitude N 20 0 24’ 27” E 81 0 03’ 56” N 20 0 24’ 27” E 81 0 04’ 14” N 20 0 24’ 48” E 81 0 04’ 14” N 20 0 24’ 54” E 81 0 03’ 56” 3 Name of River / Nallahs / Tanks / Khandri Nadi 8.5 Km. south Spring / Lakes etc. 4 Name of Reserve Forest (s), Wild life Kachhe RF Mine lease is within Sanctuary / National Parks etc. forest area Rajobidih RF 1.5 Km, E Khande PF 8.4 Km, NE Naghu RF 6.5 Km, W Pichekatta RF 4.3 Km, SSE Mardel PF 7.6 Km, SSE Ranwahi PF 8.7 Km, SSE Unochapani RF 7.0 Km, SE Magardha RF 4.5 Km, E Limodih PF 9.6 Km, NE 5 Topography of ML area Elevation : 410 m AMSL to 590 m AMSL 6 Name of Mineral mined Iron Ore M/s. Godawari Power & Ispat Ltd. 1/13 Expansion of Iron Ore Mining Lease Area from 106.60 ha. to 138.96 ha. at Village: Kachhe, Tehsil: Bhanupratappur, District: Uttar Bastar (Kanker), Chhattisgarh Pre -Feasibility R eport 7 Rate of Production (in MTPA) Existing area 7.05 lakh tonnes/annum of 106.60 Additional area 7.0 lakh tonnes/annum 32.36 ha. -

Election Commission of India Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110001

ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NIRVACHAN SADAN, ASHOKA ROAD, NEW DELHI-110001. No. ECI/PN/43 /2013 Dated: 4th October, 2013 PRESS NOTE Subject: Schedule for General Election to the Legislative Assemblies of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan and Delhi and bye-elections to fill the casual vacancies in the State Legislative Assemblies of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu – Regarding. The terms of the Legislative Assemblies of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan and Delhi are normally due to expire as follows: Chhattisgarh 04.01.2014 Madhya Pradesh 12.12.2013 Mizoram 15.12.2013 Rajasthan 31.12.2013 Delhi 17.12.2013 As per the established practice, the Election Commission holds the General Elections to the Legislative Assemblies of the States whose terms expire around the same time, together. By virtue of its powers, duties and functions under Article 324 read with Article 172(1) of the Constitution of India and Section 15 of Representation of the People Act, 1951, the Commission is required to hold elections to constitute the new Legislative Assemblies in the said States of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan and Delhi before expiry of their present terms. (1) Assembly Constituencies The total number of Assembly Constituencies in the States of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan and Delhi and seats reserved for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, as determined by the Delimitation Commission under the Delimitation Act, 2002 are as under: - States Total No. of Assembly Reserved for Reserved for Constituencies SCs STs Chhattisgarh 90 10 29 Madhya Pradesh 230 35 47 Mizoram 40 - 39 Rajasthan 200 34 25 Delhi 70 12 - 1 (2) Electoral Rolls The Electoral Rolls of all existing Assembly Constituencies in the States of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan and Delhi on the basis of the electoral rolls revised with reference to 1.1.2013 as the qualifying date and have been finally published on 12.09.2013, 24.07.2013, 16.08.2013, 06.09.2013 and 09.09.2013 respectively. -

Telephone Directory - 2017

TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - 2017 CHHATTISGARH STATE POWER HOLDING CO. LTD. TELEPHONE DIRECTORY 2017 @ CHHATTISGARH STATE POWER HOLDING COMPANY LIMITED @ CHHATTISGARH STATE POWER GENERATION COMPANY LIMITED @ CHHATTISGARH STATE POWER TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED @ CHHATTISGARH STATE POWER DISTRIBUTION COMPANY LIMITED @ CHHATTISGARH STATE POWER TRADING COMPANY LIMITED PERSONAL INFORMATION Name .............................................................................................................................................. Designation .................................................................................................................................. Office .............................................................................................................................................. Telephone No. ......................................................... Mobile No. ............................................ Residence Address ..................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................................................ Telephone No. ............................................................................................................................. Employee No. ............................................................................................................................... G.P.F. A/c No. ................................................................................................................................. -

District Survey Report Kanker

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT KANKER MINERAL RESOURCE DEPARTMENTDIRECTORATE OF GEOLOGY & MINING CHHATTISGARH 1 PREFACE District Survey Report has been prepared as per the guidelines of the Gazette of India Notification No. S.O.141(E) New Delhi, Dated 15th January 2016 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate mentioned in Appendix-X. District Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) and District Environment Assessment Committee (DEAC) has been constituted to scrutinize and sanction the environmental clearance for mining of minor minerals of lease area less than five hectares. Dated 25th July 2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change mentioned in Appendix-X. This report updated by the regional head DGM, Jagdalpur instructions issued by the Dirctor , Geology & Mining(CG) Raipur by its letter no.-1605-07/Khani-2/Rait(mool)/F. No. 38/1996, ated 01/04/2019 Any correspondence in this regard may kindly be sent in MS-Office word file and should be emailed to [email protected] or may be sent by post to Member Secretary District level Expert Appraisal Committee Mining Section CollectorateBuilding, District North BastarKanker 494334 2 CONTENTS Page No. 1. Introduction 04 Kanker District – An Overview 05 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 06 3. List of Leases (i) List of Mining Leases (Major minerals) with 07 details (ii) List of Quarry Leases with details 08 4. Details of Royalty or revenue received in last 3 09 years. 5. Details of production of Sand in last 3 years. 10 6. Details of Sand Mines. 11 7. Process of Deposition of sediments in the 13 rivers 8. -

Ifsc Code Major Bank Cg

BANK IFSC CODE MICR CODE DISTRICT CITY BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CONTACT STATE ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210311 495010002 BILASPUR BILASPUR BILASPUR IDGAH CHOWK, POLICE LINES, UMESH SRIVASTAVA CHHATTISGARH BILASPUR-495001 (OFFICER) ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211982 495010003 BILASPUR BILASPUR BILASPUR VYAPAR VIHAR NEAR SRI SAI MANGALAM, RING SACHINDRA VERAM (SR. CHHATTISGARH ROAD , VYAPAR VIHAR, MANAGER) BILASPUR-495001 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211440 495010504 BILASPUR SARGAON SILDAHA VILL & P.O. SARGAON , DIST – HEMANT SOMKUWAR, CHHATTISGARH BILASPUR , PIN - 495224 9425229797 IMRAN HAMID , 9300463968 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210475 495010506 DABHARA JANJGIR-CHAMPA DABHARA DABHARA , VILL & P.O. A.K.BOHIDAR 9179350830 & CHHATTISGARH DABHARA , DIST. JANJGIR- P. MINZ 9669438512 CHAMPA , CHHATISGARH , PIN - 495688 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210452 NON-MICR DURG BHILAINAGAR BHILAI NEW KHURSIPUR SHRI GURU SINGH SABHA S K DAS,HIMANSHU DAS,0788- CHHATTISGARH GURUDWARA NEW 2224315 KHURSIPUR,BHILAI DIST - DURG DURG CHATTISGARH 490002 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210209 NON-MICR DURG DURG DURG NAHAR COMPLEX,1ST R K SHARMA,ATUL,0788- CHHATTISGARH FLOOR,OLD BUS STAND DURG 2322843 CHATTISGARH 491001 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210548 NON-MICR DURG DURG DURG KASARIDIH 1ST FLOOR, ERAWAT SURENDRA SINGH,P K CHHATTISGARH PARISHAR PADMINAPUR, DURG MESHRAM,0788- DURG DURG CHATTISGARH 2322723/2326250 491001 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212017 NON-MICR DURG DURG SUPELA BHILLAI NAGAR PALIKA COMPLEX,G.E. DAMODAR SHETTY,MEERA CHHATTISGARH ROAD , SUPELA,BHILAI DIST - SHARMA,0788-2357289 DURG CHATTISGARH 490023 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210355 491010503 DURG KUMHARI KUMHARI KUMHARI , VILL & P.O. KUMHARI D.P.SAHOO 9907571255, CHHATTISGARH , DIST – DURG (CHHATISGARH) , S.S.PUROHIT 9770564644 PIN - 490042 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210820 APPLIED FOR JANJGIR-CHAMPA CHANDRAPUR CHANDRAPUR CHANDRAPUR, PANCHAYAT R J RAO, 9425586343, A K CHHATTISGARH BHAWAN, P.O. -

Kanker District Chhattisgarh 2012-13

GOVT. OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER BROCHURE KANKER DISTRICT CHHATTISGARH 2012-13 CHARAMA NARHARPUR BHANUPRATAPPUR KANKER DURGKONDAL ANTAGARH KOYLIBEDA Regional Director North Central Chhattisgarh Region, Reena Apartment, IInd Floor, NH-43, Pachpedi Naka, Raipur-492001 (C.G.) Ph. No. 0771-2413903, 2413689 E-mail: rdnccr- [email protected] GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF KANKER DISTRICT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE I. General 1. Location : Located in the south-western corner of the State. Long (East) : 80°24’’06’ to 81°49’’00’ Lat (North) : 19°41’’41’ to 20°33’’20’ 2. Geographical area : 6432.68 sq.km. 3. Community Development blocks : 7 no.s 4. Villages : 1003 no.s 5. Population : 7,48,593 (As per Census 2011) 6. Average annual rainfall(Last five years : 1090 mm i.e. 2007-2012) 7. Major physiographic unit : Chhattisgarh Plain & Bastar Plateau 8. River Basins and major drainage : Mahanadi Basin(covers 35% area) Major rivers and streams: (Duth, hatkal Turi,Kukari etc.) Godavari Basin(covers 65% area) Major rivers and streams: (Kotri, Jemri, Karakasa, Bharke etc) 8. Forest area : Nearly 44% of geographical area II. Major Soils 1. Alfisols : Red loamy/sandy 2. Ultisols : Yellow and Red brown III. Principal crops (2011) Crop seasons : Two (Kharif and Rabi) 1. Rice : 173596 ha 2. Pulses : 19081 ha 3. Jowar & Maize : 9551 ha 4. Wheat : 832 ha IV. Irrigation (2011) 1. Net sown area :211135 ha 2. Gross irrigated area :26850 ha a) By dug wells :4481 no.s (706 ha) b) By tube wells :5119 no.s (6515 ha) c) By tanks/ponds :649 no.s (3693 ha) d) By canals :17 no.s (7039 ha) e) By other sources :8897 ha V.