Shoulder Dystocia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

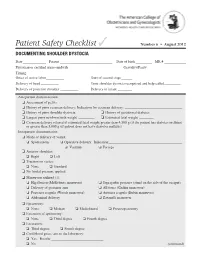

Documenting Shoulder Dystocia

Patient Safety Checklist ✓ Number 6 • August 2012 DOCUMENTING SHOULDER DYSTOCIA Date _____________ Patient _____________________________ Date of birth _________ MR # ____________ Physician or certified nurse–midwife _____________________________ Gravidity/Parity______________________ Timing: Onset of active labor __________ Start of second stage ______ Delivery of head __________ Time shoulder dystocia recognized and help called _________ Delivery of posterior shoulder __________ Delivery of infant ________ Antepartum documentation: ❏ Assessment of pelvis ❏ History of prior cesarean delivery: Indication for cesarean delivery: ________________________________ ❏ History of prior shoulder dystocia ❏ History of gestational diabetes ❏ Largest prior newborn birth weight _________ ❏ Estimated fetal weight ________ ❏ Cesarean delivery offered if estimated fetal weight greater than 4,500 g (if the patient has diabetes mellitus) or greater than 5,000 g (if patient does not have diabetes mellitus) Intrapartum documentation: ❏ Mode of delivery of vertex: ❏ Spontaneous ❏ Operative delivery: Indication: _________________________________________ ❏ Vacuum ❏ Forceps ❏ Anterior shoulder: ❏ Right ❏ Left ❏ Traction on vertex: ❏ None ❏ Standard ❏ No fundal pressure applied ❏ Maneuvers utilized (1): ❏ Hip flexion (McRoberts maneuver) ❏ Suprapubic pressure (stand on the side of the occiput) ❏ Delivery of posterior arm ❏ All fours (Gaskin maneuver) ❏ Posterior scapula (Woods maneuver) ❏ Anterior scapula (Rubin maneuver) ❏ Abdominal delivery ❏ Zavanelli maneuver -

A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of This Document Is Made Possible by Financial Contributions from Health Canada and Provincial and Territorial Governments

ICD-10-CA | CCI A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of this document is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. Unless otherwise indicated, this product uses data provided by Canada’s provinces and territories. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 www.cihi.ca [email protected] © 2018 Canadian Institute for Health Information Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Guide de codification des données en obstétrique. Table of contents About CIHI ................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

Three Typical Claims in Shoulder Dystocia Lawsuits

Three Typical Claims in Shoulder Dystocia Lawsuits Henry Lerner, MD Dr. Lerner practices obstetrics and gynecology at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts. t the end of a busy day, your office manager comes in The plaintiff’s lawyer and expert witnesses willclaim that it was holding a thick envelope. You don’t like the look on the physician’s duty to assess whether the baby was at increased her face. As she hands it to you, you see the return risk for shoulder dystocia at delivery. Plaintiffs will enumerate a Aaddress is a law firm. The envelope holds a summons indicating series of factors gleaned from their history and medical records that a malpractice lawsuit is being filed against you. The name which they will claim indicate that they were at increased risk of the patient involved seems only vaguely familiar. When for shoulder dystocia. Such factors include: you review the chart, you see that it was a delivery with a mild Prelabor risks (alleged): shoulder dystocia—four years ago. ■■ Suspected big baby As an obstetrician who has been in practice for more than 28 ■■ Gestational diabetes years, had numerous shoulder dystocia deliveries, and reviewed ■■ Large maternal weight gain close to 100 shoulder dystocia medical-legal cases, I have seen ■■ Large uteri fundal height measurement the above scenario played out frequently. In some cases, the ■■ Small pelvis delivery was catastrophic and the obstetrician was unsurprised ■■ Small maternal stature by the lawsuit. In most cases, however, the delivery was just ■■ Previous large baby one of hundreds or thousands the doctor has done over the ■■ Known male fetus years…and forgotten. -

Shoulder Dystocia Abnormal Placentation Umbilical Cord

Obstetric Emergencies Shoulder Dystocia Abnormal Placentation Umbilical Cord Prolapse Uterine Rupture TOLAC Diabetic Ketoacidosis Valerie Huwe, RNC-OB, MS, CNS & Meghan Duck RNC-OB, MS, CNS UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Outreach Services, Mission Bay Objectives .Highlight abnormal conditions that contribute to the severity of obstetric emergencies .Describe how nurses can implement recommended protocols, procedures, and guidelines during an OB emergency aimed to reduce patient harm .Identify safe-guards within hospital systems aimed to provide safe obstetric care .Identify triggers during childbirth that increase a women’s risk for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Postpartum Depression . Incorporate a multidisciplinary plan of care to optimize care for women with postpartum emergencies Obstetric Emergencies • Shoulder Dystocia • Abnormal Placentation • Umbilical Cord Prolapse • Uterine Rupture • TOLAC • Diabetic Ketoacidosis Risk-benefit analysis Balancing 2 Principles 1. Maternal ‒ Benefit should outweigh risk 2. Fetal ‒ Optimal outcome Case Presentation . 36 yo Hispanic woman G4 P3 to L&D for IOL .IVF Pregnancy .3 Prior vaginal births: 7.12, 8.1, 8.5 (NCB) .Late to care – EDC ~ 40-41 weeks .GDM Type A2 – somewhat uncontrolled .4’11’’ .Hx of Lupus .BMI 40 .Gained ~ 40 lbs during pregnancy Question: What complication is she a risk for? a) Placental abruption b) Thyroid Storm c) Preeclampsia with severe features d) Shoulder dystocia e) Uterine prolapse Case Presentation . 36 yo Hispanic woman G4 P3 to L&D for IOL .IVF Pregnancy .3 -

Pretest Obstetrics and Gynecology

Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the prod- uct information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Twelfth Edition Karen M. Schneider, MD Associate Professor Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Texas Houston Medical School Houston, Texas Stephen K. Patrick, MD Residency Program Director Obstetrics and Gynecology The Methodist Health System Dallas Dallas, Texas New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Obstetrics 2002

OBSTETRICS Dr. P. Bernstein Laura Loijens and Colleen McDermott, chapter editors Tracy Chin, associate editor NORMAL OBSTETRICS . 2 ABNORMAL LABOUR . .34 Definitions Induction of Labour Diagnosis of Pregnancy Induction Methods Investigations Augmentation of Labour Maternal Physiology Abnormal Progress of Labour Umbilical Cord Prolapse PRENATAL CARE . 5 Shoulder Dystocia Preconception Counseling Breech Presentation Initial Visit Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) Subsequent Visits Uterine Rupture Gestation-Dependent Management Amniotic Fluid Embolus Prenatal Diagnosis OPERATIVE OBSTETRICS . .39 FETAL MONITORING. 8 Indications for Operative Vaginal Delivery Antenatal Monitoring Forceps Intra-Partum Monitoring Vacuum Extraction Lacerations MULTIPLE GESTATION . .12 Episiotomy Background Cesarean Delivery Management Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome OBSTETRICAL ANESTHESIA . .40 Pain Pathways During Labour MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN PREGNANCY . .13 Analgesia Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Anesthesia Iron Deficiency Anemia Folate Deficiency Anemia NORMAL PUERPERIUM . .42 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) Definition Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) Post-Delivery Examination Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Breast Hyperemesis Gravidarum Uterus Isoimmunization Lochia Infections During Pregnancy Postpartum Care ANTENATAL HEMORRHAGE . .22 PUERPERAL COMPLICATIONS . .42 First and Second Trimester Bleeding Retained Placenta Therapeutic Abortions Uterine Inversion Third Trimester Bleeding Postpartum Pyrexia Placenta Previa Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) Abruptio Placentae -

Intractable Shoulder Dystocia: a Posterior Axilla Maneuver May Save the Day

Intractable shoulder dystocia: A posterior axilla maneuver may save the day My preferred posterior axilla maneuver is the Menticoglou maneuver. Here, a look at your options and steps to delivery. Robert L. Barbieri, MD houlder dystocia is an unpredictable 7. delivering the posterior arm obstetric emergency that challenges 8. considering the Gaskin all-four maneuver. S all obstetricians and midwives. In response to a shoulder dystocia emergency, When initial management most clinicians implement a sequence of steps are not enough IN THIS well-practiced steps that begin with early If this sequence of steps does not result in ARTICLE recognition of the problem, clear communi- successful vaginal delivery, additional op- cation of the emergency with delivery room tions include: clavicle fracture, cephalic re- staff, and a call for help to available clinicians. placement followed by cesarean delivery Menticoglou Management steps may include: (Zavanelli maneuver), symphysiotomy, or maneuver 1. instructing the mother to stop pushing and fundal pressure combined with a rotational page 18 moving the mother’s buttocks to the edge maneuver. Another simple intervention that of the bed is not discussed widely in medical textbooks Importance of 2. ensuring there is not a tight nuchal cord or taught during training is the posterior simulation 3. committing to avoiding the use of excessive axilla maneuver. page 20 force on the fetal head and neck 4. considering performing an episiotomy 5. performing the McRoberts maneuver com- Posterior axilla maneuvers bined with suprapubic pressure Varying posterior axilla maneuvers have 6. using a rotational maneuver, such as the been described by many expert obstetri- Woods maneuver or the Rubin maneuver cians, including Willughby (17th Cen- tury),1 Holman (1963),2 Schramm (1983),3 4 Dr. -

Medicalverdicts

Medical Verdicts Notable judgmeNts aNd settlemeNts gravida in septic shock; partners during her pregnancy. were signs missed? } physician’s DEFENSE Negative results of a Herpes Select Test 6 months wiTh sEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN AND VOMITING at 14 before birth made follow-up testing weeks’ gestation, a 30-year-old woman was brought unnecessary. She must have contracted by ambulance to the hospital. After initial evalua- the disease after testing had been per- tion did not reveal a cause of her symptoms, she was formed. She had no symptoms that transferred to the antepartum unit for observation. made the viral disease diagnosable at The mother developed hypotension and a diagnosis of septic shock delivery. The child’s symptoms sug- was made. Fetal cardiac activity ceased and the woman developed intesti- gested transplacental transmission of nal ischemia. She underwent an intestinal transplant several months later. herpes; a cesarean delivery would not have changed the outcome. } paTiEnT’s cLAIM Both treating physicians and the nursing staff failed to } VERDICT A Nevada defense react to her intermittently low blood pressure, and failed to diagnose or verdict was returned. treat septic shock in a timely manner. } defenDanTs’ DEFENSE The patient was properly monitored and treated. } VERDICT A $11,500,000 Illinois verdict was returned against the hospital. home birth A defense verdict was returned for both physicians. emergency DuRing a homE birth managed by severe abdominal pain after surgery. a midwife, the baby was born after Lethal outcome of } defenDanTs’ DEFENSE Bowel perfo- the mother pushed for 2 hours and ovarian cystectomy ration is a known complication of the 47 minutes. -

Rupture of the Symphysis Pubis During Vaginal Delivery Followed

REFERENCES Present status and future role of the Zavanelli maneuver. 1. Sandberg EC. The Zavanelli maneuver: A potentially rev- Obstet Gynecol 1993;82:847–50. olutionary method for the resolution of shoulder dystocia. 5. Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Goodwin TM. Brachial Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;152:479–84. plexus palsy: An in utero injury? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2. Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Goodwin TM. Obstetric 1999;180:1303–7. maneuvers for shoulder dystocia and associated fetal mor- 6. Sandmire HF, DeMott RK. Erb’s palsy: Concepts of causa- bidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178:1126–30. tion. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:940–2. 3. Sandberg EC. The Zavanelli maneuver: 12 years of recorded experience. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:312–7. Received March 6, 2002. Received in revised form April 25, 2002. 4. O’Leary JA. Cephalic replacement for shoulder dystocia: Accepted May 13, 2002. Rupture of the Symphysis Pubis pregnancies. We present a case of a woman with a 5-cm symphyseal separation with vaginal delivery followed by During Vaginal Delivery two subsequent normal pregnancies. Followed by Two Subsequent Uneventful Pregnancies CASE A young, healthy primigravida experienced spontane- Patrick Culligan, MD, Stephanie Hill, and ous rupture of membranes followed by spontaneous Michael Heit, MD, MSPH labor at 37 weeks’ gestation. Her pregnancy had been Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Department of uneventful. Cervical dilatation progressed to 4 cm 2 Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Louisville Health Sciences Center, Lou- hours after her membranes ruptured and she was given isville, Kentucky epidural anesthesia. She progressed through the active phase of labor without oxytocin augmentation, and was BACKGROUND: Rupture of the symphysis pubis during vag- fully dilated 6 hours after the placement of her epidural inal delivery is a rare but debilitating complication. -

Obstetrical Emergencies – Shoulder Dystocia

Registered Nurse Initiated Activities Decision Support Tool No. 8B: Obstetrical Emergencies – Shoulder Dystocia Decision support tools are evidenced-based documents used to guide the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of client-specific clinical problems. When practice support tools are used to direct practice, they are used in conjunc- tion with clinical judgment, available evidence, and following discussion with colleagues. Nurses also consider client needs and preferences when using decision support tools to make clinical decisions. The Nurses (Registered) and Regulation: (6)(1)(h.1) authorizes registered nurses to “manage labour in Nurse Practitioners Regulation: an institutional setting if the primary maternal care provider is absent.” Indications: In an nurse-assisted birth there is inability of the baby’s shoulders to deliver spontaneously Related Resources, Policies, and Neonatal Resuscitation Program Provider Course Standards: Definitions and Abbreviations: Shoulder Dystocia – When the head emerges, it retracts against the perineum (turtle sign) and external rotation does not occur thus the anterior shoulder cannot pass under the pubic arch. The delivery requires additional obstetric maneuvers as there is an inability of the shoulders to deliver spontaneously or with supportive maneuvers, i.e. maternal expulsive effort and gentle downward pressure on the head McRobert’s Maneuver – Supine position, head of bed flat – The woman’s hips and knees are flexed against her abdomen. Suprapubic Pressure – With the heel of the clasped -

Abnormalities of Labor and Delivery

Abnormalities of labour and delivery Artúr Beke MD PhD Semmelweis University Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Baross Street Abnormalities of labor and delivery • 1. Fetal malpositions and malpresentations • 2. Uterine dystocia • 3. Shoulder dystocia • 4. Premature rupture of the membranes • 5. Fetal distress • 6. Preterm delivery • 7. Twin delivery Artur Beke - Abnormalities of Labour and Delivery - 2019 1. Fetal malposition and malpresentations Artur Beke - Abnormalities of Labour and Delivery - 2019 Fetal malposition and malpresentations • A./ Abnormal presentation – Breech presentation – Transverse or oblique lie (shoulder presentation) • B./ Abnormal position – High sagittal position – Obliquity • C./ Abnormalities of flexion – Deflexion of the head • D./ Abnormalities of rotation Artur Beke - Abnormalities of Labour and Delivery - 2019 A./ ABNORMAL PRESENTATION • Cephalic presentation 96.5% • Breech presentation 3.0% • Transverse or oblique lie 0.5% Artur Beke - Abnormalities of Labour and Delivery - 2019 Breech presentation • Fetal buttocks or lower extremities present • 3% of all deliveries • At the 30th week 25% of fetuses • After 36th week no change in position Artur Beke - Abnormalities of Labour and Delivery - 2019 Types of breech presentation • Frank breech - Extended legs (Simple) (65%) • Complete breech - Flexed legs (25%) • Incomplete breech - Footling or knee presentation (10%) Artur Beke - Abnormalities of Labour and Delivery - 2019 Diagnosis of breech presentation • Leopold -

Abdominal Access for Shoulder Dystocia As a Last Resort – a Case Report Abdominaler Zugang Bei Schulterdystokie Als Ultima Ratio – Ein Fallbericht

634 GebFra Science Abdominal Access for Shoulder Dystocia as a Last Resort – a Case Report Abdominaler Zugang bei Schulterdystokie als Ultima Ratio – ein Fallbericht Authors A. Enekwe1, R. Rothmund2, B. Uhl1 Affiliations 1 Gynaecology Deparment, St-Vinzenz-Hospital Dinslaken, Dinslaken, Germany 2 University Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tübingen, Germany Key words Abstract Zusammenfassung l" shoulder dystocia ! ! l" abdominal rescue Shoulder dystocia is the term used to describe Die Schulterdystokie beschreibt einen Geburts- l" ʼ Erb s palsy failure to progress in labour after the head has stillstand nach Geburt des Kopfes aufgrund unzu- Schlüsselwörter been delivered due to insufficient rotation of the reichender Schulterdrehung. Das Ereignis trifft l" Schulterdystokie shoulders. It is unpredictable and cannot be pre- die geburtshilflich tätige Person in der Regel völ- l" abdominaler vented by the midwife or the obstetrician. We lig unerwartet. Es wird hier über einen Fall einer Rettungsversuch report here on a severe case of shoulder dystocia, schweren Schulterdystokie berichtet, bei dem die l" Armplexusparese where delivery of the shoulder was finally Schulterlösung durch direkten Druck auf die vor- achieved through direct pressure on the anterior dere Schulter nach Laparotomie und Uterotomie shoulder after laparotomy and uterotomy with bei gleichzeitigem Woods-Screw-Manöver von concurrent vaginal Woods screw manoeuvre and vaginal mit anschließender vaginaler Entbindung was followed by vaginal delivery. The patient pre- gelang. Die Patientin wies eine Adipositas und die sented risk factors like maternal obesity and ad- Gabe von wehenfördernden Mitteln als Risikofak- ministration of labour-inducing drugs. After dif- toren auf. Nach erfolgloser Ausführung des McRo- ferent manoeuvres like McRoberts manoeuvre berts-Manövers und diverser Manöver zur inne- and several manoeuvres for internal rotation ren Rotation wurde eine Notlaparotomie durch- were carried out unsuccessfully, an emergency geführt.