Process Approaches to Consciousness in Psychology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's Philosophy Frederick Joseph Parker

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1936 The development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy Frederick Joseph Parker Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Frederick Joseph, "The development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy" (1936). Master's Theses. Paper 912. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. mE Dt:VEto!l..mm oa llS. At..~"1lr:D !JG'lt'fR ~!EREAli •a MiILOSO?ll' A. thesis SUbm1tte4 to the Gradus:te i'acnl ty in cana1:.at1: f!Jr tbe degree of llaste,-. of Arts Univerait7 of !llcuor.&a Jnno 1936 PREF!~CE The modern-·wr1 ter in the field of Philosophy no doubt recognises the ilfficulty of gaining an ndequate and impartial hearing from the students of his own generation. It seems that one only becomes great at tbe expense of deatb. The university student is often tempted to close his study of philosophy- after Plato alld Aristotle as if the final word has bean said. The writer of this paper desires to know somethi~g about the contribution of the model~n school of phiiiosophers. He has chosen this particular study because he believes that Dr. \i'hi tehesa bas given a very thoughtful interpretation of the universe .. This paper is in no way a substitute for a first-hand study of the works of Whitehead. -

A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws Andrew Michael Winters University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-20-2015 A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws Andrew Michael Winters University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy of Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Winters, Andrew Michael, "A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5603 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws by Andrew Michael Winters A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Douglas Jesseph, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Alexander Levine, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Otávio Bueno, Ph.D. John Carroll, Ph.D. Eric Winsberg, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 20th, 2015 Keywords: Metaphysics, Epistemology, Naturalism, Ontology Copyright © 2015, Andrew Michael Winters DEDICATION For Amie ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my co-chairs, Doug Jesseph and Alex Levine, for providing amazing support in all aspects of my tenure at USF. I greatly appreciate the numerous conversations with my committee members, Roger Ariew, Otávio Bueno, John Carroll, and Eric Winsberg, which resulted in a (hopefully) more refined and clearer dissertation. -

William James As American Plato? Scott Sinclair

WILLIAM JAMES AS AMERICAN PLATO? ______________________________________________________________________________ SCOTT SINCLAIR ABSTRACT Alfred North Whitehead wrote a letter to Charles Hartshorne in 1936 in which he referred to William James as the American Plato. Especially given Whitehead’s admiration of Plato, this was a high compliment to James. What was the basis for this compliment and analogy? In responding to that question beyond the partial and scattered references provided by Whitehead, this article briefly explores the following aspects of the thought of James in relation to Whitehead: the one and the many, the denial of Cartesian dualism, James’s background in physiology, refutation of Zeno’s paradoxes, religious experience, and other kinships. In the end, the author agrees with Robert Neville that James had seminal ideas which could correctly result in a complimentary analogy with Plato. Therefore, a greater focus on the important thought of James is a needed challenge in contemporary philosophy. Michel Weber provided a very helpful article in two parts entitled, “Whitehead’s Reading of James and Its Context,” in the spring 2002 and fall 2003 editions of Streams of William James. Weber began his article with a reference to Bertrand Russell: “When Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) visited Harvard in 1936, ‘there were two heroes in his lectures – Plato and James.’”1 Although he goes on to affirm that Whitehead could have said the same, Weber either overlooks the fact, or is not aware, that Whitehead actually did compare James to Plato in his January 2, 1936 hand-written letter to Charles Hartshorne, as printed by Whitehead’s biographer, Victor Lowe: European philosophy has gone dry, and cannot make any worthwhile use of the results of nineteenth century scholarship. -

Quantum Logical Causality, Category Theory, and the Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead

Quantum Logical Causality, Category Theory, and the Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead Connecting Zafiris’ Category Theoretic Models of Quantum Spacetime and the Logical-Causal Formalism of Quantum Relational Realism Workshop Venue: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Chair for Philosophy (building RAC) Raemistrasse 36, 8001 Zurich Switzerland January 29 – 30, 2010 I. Aims and Motivation Recent work in the natural sciences—most notably in the areas of theoretical physics and evolutionary biology—has demonstrated that the lines separating philosophy and science have all but vanished with respect to current explorations of ‘fundamental’ questions (e.g., string theory, multiverse cosmologies, complexity-emergence theories, the nature of mind, etc.). The centuries-old breakdown of ‘natural philosophy’ into the divorced partners ‘philosophy’ and ‘science,’ therefore, must be rigorously re- examined. To that end, much of today’s most groundbreaking scholarship in the natural sciences has begun to include explicit appeals to interdisciplinary collaboration among the fields of applied natural sciences, mathematics and philosophy. This workshop will be dedicated to the question of how a philosophical-metaphysical theory can be fruitfully applied to basic conceptualizations in the natural sciences. More narrowly, we will explore the process oriented metaphysical scheme developed by philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) and Michael Epperson’s application of this scheme to recent work in quantum mechanics, and the relation of these to Elias Zafiris’s category theoretic model of quantum event structures. Our aim is to give participants from various fields of expertise (see list below) the opportunity to exchange their specialized knowledge in the context of a collaborative exploration of the fundamental questions raised by recent scholarship in physics and mathematics. -

Iv. Causal Interactions of Consciousness, Unconscious Mind and Brain1

IV. CAUSAL INTERACTIONS OF CONSCIOUSNESS, UNCONSCIOUS MIND AND BRAIN1 MAX VELMANS 1. WHAT NEEDS TO BE EXPLAINED The potential effect of the mind on the body is also taken for granted in psychosomatic medicine. But how the conscious mind exercises its influ- ence is not easy to understand. In principle, there are four distinct ways in which body/brain and mind/consciousness might enter into causal relation- ships. There might be physical causes of physical states, physical causes of mental states, mental causes of mental states, and mental causes of physical states. Establishing which forms of causation are effective in practice is important, not just for a deeper understanding of mind/body interactions, but also for the proper treatment of some forms of illness and disease. Within conventional medicine, physicalÆphysical causation is taken for granted. Consequently, the proper treatment for physical disorders is assumed to be some form of physical intervention. Psychiatry takes the efficacy of physicalÆmental causation for granted, along with the assump- tion that the proper treatment for psychological disorders may involve psychoactive drugs, neurosurgery and so on. Many forms of psychotherapy take mentalÆmental causation for granted, and assume that psychological disorders can be alleviated by means of “talking cures”, guided imagery, hypnosis and other forms of mental intervention. Psychosomatic medicine assumes that mentalÆphysical causation can be effective. Consequently, under some circumstances, a physical disorder (for example, hysterical paralysis) may require a mental (psychotherapeutic) intervention. Given the extensive evidence for all these causal interactions (cf. readings in Velmans 1996a), how are we to make sense of them? 2. -

Evaluating Empirical Research

EVALUATING EMPIRICAL RESEARCH A NTIOCH It is important to maintain an objective and respectful tone as you evaluate others’ empirical studies. Keep in mind that study limitations are often a result of the epistemological limitations of real life research situations rather than the laziness or ignorance of the researchers. It’s U NIVERSITY NIVERSITY normal and expected for empirical studies to have limitations. Having said that, it’s part of your job as a critical reader and a smart researcher to provide a fair assessment of research done on your topic. B.A. Maher’s guidelines (as cited in Cone and Foster, 2008, pp 104- V 106) are useful in thinking of others’ studies, as well as for writing up your IRTIUAL own study. Here are the recommended questions to consider as you read each section of an article. As you think of other questions that are particularly W important to your topic, add them to the list. RITING Introduction Does the introduction provide a strong rationale for why the study is C ENTER needed? Are research questions and hypotheses clearly articulated? (Note that research questions are often presented implicitly within a description of the purpose of the study.) Method Is the method described so that replication is possible without further information Participants o Are subject recruitment and selection methods described? o Were participants randomly selected? Are there any probable biases in sampling? A NTIOCH o Is the sample appropriate in terms of the population to which the researchers wished to generalize? o Are characteristics of the sample described adequately? U NIVERSITY NIVERSITY o If two or more groups are being compared, are they shown to be comparable on potentially confounding variables (e.g. -

Internationalizing the University Curricula Through Communication

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 428 409 CS 510 027 AUTHOR Oseguera, A. Anthony Lopez TITLE Internationalizing the University Curricula through Communication: A Comparative Analysis among Nation States as Matrix for the Promulgation of Internationalism, through the Theoretical Influence of Communication Rhetors and International Educators, Viewed within the Arena of Political-Economy. PUB DATE 1998-12-00 NOTE 55p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association of Puerto Rico (18th, San Juan, Puerto Rico, December 4-5, 1998). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Curriculum; *Communication (Thought Transfer); Comparative Analysis; *Educational Change; Educational Research; Foreign Countries; Global Approach; Higher Education; *International Education IDENTIFIERS *Internationalism ABSTRACT This paper surveys the current situation of internationalism among the various nation states by a comparative analysis, as matrix, to promulgate the internationalizing process, as a worthwhile goal, within and without the college and university curricula; the theoretical influence and contributions of scholars in communication, international education, and political-economy, moreover, become allies toward this endeavor. The paper calls for the promulgation of a new and more effective educational paradigm; in this respect, helping the movement toward the creation of new and better schools for the next millennium. The paper profiles "poorer nations" and "richer nations" and then views the United States, with its enormous wealth, leading technology, vast educational infrastructure, and its respect for democratic principles, as an agent with agencies that can effect positive consequences to ameliorating the status quo. The paper presents two hypotheses: the malaise of the current educational paradigm is real, and the "abertura" (opening) toward a better paradigmatic, educational pathway is advisable and feasible. -

Process and (Mixed) Reality: a Process Philosophy for Interaction in Mixed Reality Environments

Process and (Mixed) Reality: A Process Philosophy for Interaction in Mixed Reality Environments Timothy Barker iCinema Centre for Interactive Cinema, The University of New South Wales ABSTRACT These events are experienced within interaction with MR environments as interconnections are formed between multiple Mixed Reality (MR) environments deployed in the service of art contemporaneous entities, including the coded regime of the present a radical shift in aesthetics. These relatively recent artistic digital and the physical and affective regime of the user. experiments open up many questions relating to the traditional The interactive encounter of media art that takes place in MR distinction between subjects and objects. I seek to grapple with environments is essentially performative; the work of art is these questions of reception by viewing works by pioneering brought into being through the processes of interaction, the artists such as Jeffrey Shaw, Dennis Del Favero, Ulrike Gabriel process by which the user physically does something in order to and the artist group Blast Theory. Rather than viewing interaction activate the work. In this sense the aesthetics of interactive media within the reductive logic of a psychologized subject that art always involve becoming rather than being; in short, they apprehends a static object – that is the case in so much aesthetic always involve process. Thus, when we think about the theory – I seek to position the aesthetic encounter with MR performative nature of both interaction and technology, the environments as a hybrid process. In this paper, by using A. N. distinction between the way in which something is performed and Whitehead's process philosophy, I propose interaction as the the way in which something is aesthetically comprehended cannot coming together of two conditions; the condition of the machine be maintained. -

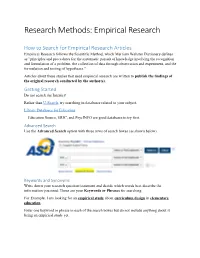

Research Methods: Empirical Research

Research Methods: Empirical Research How to Search for Empirical Research Articles Empirical Research follows the Scientific Method, which Merriam Webster Dictionary defines as "principles and procedures for the systematic pursuit of knowledge involving the recognition and formulation of a problem, the collection of data through observation and experiment, and the formulation and testing of hypotheses." Articles about these studies that used empirical research are written to publish the findings of the original research conducted by the author(s). Getting Started Do not search the Internet! Rather than U-Search, try searching in databases related to your subject. Library Databases for Education Education Source, ERIC, and PsycINFO are good databases to try first. Advanced Search Use the Advanced Search option with three rows of search boxes (as shown below). Keywords and Synonyms Write down your research question/statement and decide which words best describe the information you need. These are your Keywords or Phrases for searching. For Example: I am looking for an empirical study about curriculum design in elementary education. Enter one keyword or phrase in each of the search boxes but do not include anything about it being an empirical study yet. To retrieve a more complete list of results on your subject, include synonyms and place the word or in between each keyword/phrase and the synonyms. For Example: elementary education or primary school or elementary school or third grade In the last search box, you may need to include words that focus the search towards empirical research: study or studies, empirical research, qualitative, quantitative, methodology, Nominal (Ordinal, Interval, Ratio) or other terms relevant to empirical research. -

Peirce for Whitehead Handbook

For M. Weber (ed.): Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought Ontos Verlag, Frankfurt, 2008, vol. 2, 481-487 Charles S. Peirce (1839-1914) By Jaime Nubiola1 1. Brief Vita Charles Sanders Peirce [pronounced "purse"], was born on 10 September 1839 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Sarah and Benjamin Peirce. His family was already academically distinguished, his father being a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard. Though Charles himself received a graduate degree in chemistry from Harvard University, he never succeeded in obtaining a tenured academic position. Peirce's academic ambitions were frustrated in part by his difficult —perhaps manic-depressive— personality, combined with the scandal surrounding his second marriage, which he contracted soon after his divorce from Harriet Melusina Fay. He undertook a career as a scientist for the United States Coast Survey (1859- 1891), working especially in geodesy and in pendulum determinations. From 1879 through 1884, he was a part-time lecturer in Logic at Johns Hopkins University. In 1887, Peirce moved with his second wife, Juliette Froissy, to Milford, Pennsylvania, where in 1914, after 26 years of prolific and intense writing, he died of cancer. He had no children. Peirce published two books, Photometric Researches (1878) and Studies in Logic (1883), and a large number of papers in journals in widely differing areas. His manuscripts, a great many of which remain unpublished, run to some 100,000 pages. In 1931-58, a selection of his writings was arranged thematically and published in eight volumes as the Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Beginning in 1982, a number of volumes have been published in the series A Chronological Edition, which will ultimately consist of thirty volumes. -

What Is Philosophy.Pdf

I N T R O D U C T I O N What Is Philosophy? CHAPTER 1 The Task of Philosophy CHAPTER OBJECTIVES Reflection—thinking things over—. [is] the beginning of philosophy.1 In this chapter we will address the following questions: N What Does “Philosophy” Mean? N Why Do We Need Philosophy? N What Are the Traditional Branches of Philosophy? N Is There a Basic Method of Philo- sophical Thinking? N How May Philosophy Be Used? N Is Philosophy of Education Useful? N What Is Happening in Philosophy Today? The Meanings Each of us has a philos- “having” and “doing”—cannot be treated en- ophy, even though we tirely independent of each other, for if we did of Philosophy may not be aware of not have a philosophy in the formal, personal it. We all have some sense, then we could not do a philosophy in the ideas concerning physical objects, our fellow critical, reflective sense. persons, the meaning of life, death, God, right Having a philosophy, however, is not suffi- and wrong, beauty and ugliness, and the like. Of cient for doing philosophy. A genuine philo- course, these ideas are acquired in a variety sophical attitude is searching and critical; it is of ways, and they may be vague and confused. open-minded and tolerant—willing to look at all We are continuously engaged, especially during sides of an issue without prejudice. To philoso- the early years of our lives, in acquiring views phize is not merely to read and know philoso- and attitudes from our family, from friends, and phy; there are skills of argumentation to be mas- from various other individuals and groups. -

Philosophy — PHIL 1310 Prof

Introduction to Philosophy — PHIL 1310 Prof. Thomas — TR 10:50-12:05 (CRN: 12211) Philosophy Prof. John — WEB (CRN: 11862) This course is a survey of basic themes in philosophy, addressing & Religious Studies such fundamental concerns as the nature of morality and beauty, the relation of mind and body, and the existence of free will, through discussion and analysis of readings. Course Listings Introduction to Critical Thinking — PHIL 1330 (CRN: 11863) Prof. Jones-Cathcart — WEB Spring 2015 An introduction to reasoning skills. This course focuses on the recognition of informal fallacies and the nature, use, and evaluation of arguments, as well as the basic characteristics of inductive and deductive arguments. Introduction to Logic — PHIL 2350 (CRN: 12218) Prof. Merrick — MWF 11:00-11:50 An introduction to deductive logic including translation of sentences into formal systems, immediate inferences, syllogisms, formal fallacies, proofs of validity, and quantification. Ethics and Society — PHIL 2320 multiple sections, see Schedule of Classes This course features a study of selected texts reflecting a variety of ethical systems—with at least one major text from each of four historical periods (antiquity, medieval, early modern, and contemporary). Ethical theories examined will include: deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue theory. Kant and the 19th Century — PHIL 3321 (CRN: 13276) Prof. Merrick — MWF 9:00-9:50 Contemporary Ethical Theory — PHIL 3341 (CRN: 12219) Prof. Jauss — MWF 10:00-10:50 We will begin with Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (the First Critique) and consider this text according to its established The subject matter of ethics includes not only straightforwardly objective: namely, to offer a critique of reason by the use of reason.