Strengthening the Us Financial System And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Business and Conservative Groups Helped Bolster the Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During the Second Fundraising Quarter of 2021

Big Business And Conservative Groups Helped Bolster The Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During The Second Fundraising Quarter Of 2021 Executive Summary During the 2nd Quarter Of 2021, 25 major PACs tied to corporations, right wing Members of Congress and industry trade associations gave over $1.5 million to members of the Congressional Sedition Caucus, the 147 lawmakers who voted to object to certifying the 2020 presidential election. This includes: • $140,000 Given By The American Crystal Sugar Company PAC To Members Of The Caucus. • $120,000 Given By Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s Majority Committee PAC To Members Of The Caucus • $41,000 Given By The Space Exploration Technologies Corp. PAC – the PAC affiliated with Elon Musk’s SpaceX company. Also among the top PACs are Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and the National Association of Realtors. Duke Energy and Boeing are also on this list despite these entity’s public declarations in January aimed at their customers and shareholders that were pausing all donations for a period of time, including those to members that voted against certifying the election. The leaders, companies and trade groups associated with these PACs should have to answer for their support of lawmakers whose votes that fueled the violence and sedition we saw on January 6. The Sedition Caucus Includes The 147 Lawmakers Who Voted To Object To Certifying The 2020 Presidential Election, Including 8 Senators And 139 Representatives. [The New York Times, 01/07/21] July 2021: Top 25 PACs That Contributed To The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million The Top 25 PACs That Contributed To Members Of The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million During The Second Quarter Of 2021. -

CDIR-2018-10-29-VA.Pdf

276 Congressional Directory VIRGINIA VIRGINIA (Population 2010, 8,001,024) SENATORS MARK R. WARNER, Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in Indianapolis, IN, December 15, 1954; son of Robert and Marge Warner of Vernon, CT; education: B.A., political science, George Washington University, 1977; J.D., Harvard Law School, 1980; professional: Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, 2002–06; chairman of the National Governor’s Association, 2004– 05; religion: Presbyterian; wife: Lisa Collis; children: Madison, Gillian, and Eliza; committees: Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Budget; Finance; Rules and Administration; Select Com- mittee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2008; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2014. Office Listings http://warner.senate.gov 475 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–2023 Chief of Staff.—Mike Harney. Legislative Director.—Elizabeth Falcone. Communications Director.—Rachel Cohen. Press Secretary.—Nelly Decker. Scheduler.—Andrea Friedhoff. 8000 Towers Crescent Drive, Suite 200, Vienna, VA 22182 ................................................... (703) 442–0670 FAX: 442–0408 180 West Main Street, Abingdon, VA 24210 ............................................................................ (276) 628–8158 FAX: 628–1036 101 West Main Street, Suite 7771, Norfolk, VA 23510 ........................................................... (757) 441–3079 FAX: 441–6250 919 East Main Street, Richmond, VA 23219 ........................................................................... -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

Congress of the United States

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20510 June 16, 2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW Washington, D.C. 20554 Dear Commissioners: On behalf of our constituents, we write to thank you for the Federal Communications Commission’s (Commission’s) efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The work the Commission has done, including the Keep Americans Connected pledge and the COVID-19 Telehealth Program, are important steps to address the need for connectivity as people are now required to learn, work, and access healthcare remotely. In addition to these efforts, we urge you to continue the important, ongoing work to close the digital divide through all means available, including by finalizing rules to enable the nationwide use of television white spaces (TVWS). The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the consequences of the remaining digital divide: many Americans in urban, suburban, and rural areas still lack access to a reliable internet connection when they need it most. Even before the pandemic broadband access challenges have put many of our constituents at a disadvantage for education, work, and healthcare. Stay-at-home orders and enforced social distancing intensify both the problems they face and the need for cost- effective broadband delivery models. The unique characteristics of TVWS spectrum make this technology an important tool for bridging the digital divide. It allows for better coverage with signals traveling further, penetrating trees and mountains better than other spectrum bands. Under your leadership, the FCC has taken significant bipartisan steps toward enabling the nationwide deployment of TVWS, including by unanimously adopting the February 2020 notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM), which makes several proposals that we support. -

May 11, 2020 the Honorable Elaine L. Chao Secretary of the Department of Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 N

May 11, 2020 The Honorable Elaine L. Chao Secretary of the Department of Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Secretary Chao, We write to bring your attention to the Port of Virginia's application to the 2020 Port Infrastructure Development Discretionary Grants Program to increase on-terminal rail capacity at their Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) facility in Norfolk, Virginia. If awarded, the funds will help increase safety, improve efficiency, and increase the reliability of the movement of goods. We ask for your full and fair consideration. The Port of Virginia is one of the Commonwealth's most powerful economic engines. On an annual basis, the Port is responsible for nearly 400,000 jobs and $92 billion in spending across our Commonwealth and generates 7.5% of our Gross State Product. The Port of Virginia serves as a catalyst for commerce throughout the Commonwealth of Virginia and beyond. To expand its commercial impact, the Port seeks to use this funding to optimize its central rail yard at NIT. The Port's arrival and departure of cargo by rails is the largest of any port on the East Coast, and the proposed optimization will involve the construction of two new rail bundles containing four tracks each for a total of more than 10,000 additional feet of working track. This project will improve efficiency, allow more cargo to move through the facility, improve the safety of operation, remove more trucks from the highways, and generate additional economic development throughout the region. The Port of Virginia is the only U.S. -

We Are Not Ready Policymaking in the Age of Environmental Breakdown Final Report

Institute for Public Policy Research WE ARE NOT READY POLICYMAKING IN THE AGE OF ENVIRONMENTAL BREAKDOWN FINAL REPORT Laurie Laybourn-Langton, Joshua Emden and Tom Hill June 2020 ABOUT IPPR IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, is the UK’s leading progressive think tank. We are an independent charitable organisation with our main offices in London. IPPR North, IPPR’s dedicated think tank for the North of England, operates out of offices in Manchester and Newcastle, and IPPR Scotland, our dedicated think tank for Scotland, is based in Edinburgh. Our purpose is to conduct and promote research into, and the education of the public in, the economic, social and political sciences, science and technology, the voluntary sector and social enterprise, public services, and industry and commerce. IPPR 14 Buckingham Street London WC2N 6DF T: +44 (0)20 7470 6100 E: [email protected] www.ippr.org Registered charity no: 800065 (England and Wales), SC046557 (Scotland) This paper was first published in June 2020. © IPPR 2020 The contents and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors only. The progressive policy think tank CONTENTS Summary ..........................................................................................................................3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................7 2. Sustainability ...........................................................................................................10 Environmental breakdown -

Conversations on Rethinking Human Development

Conversations on Rethinking Human Development A global dialogue on human development in today’s world Conversations on Rethinking Human Development is produced by the International Science Council, as part of a joint initiative by the International Science Council and the United Nations Development Programme. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the ISC or the UNDP concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The Conversations on Rethinking Human Development project team is responsible for the overall presentation. Each author is responsible for the facts contained in his/her article or interview, and the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of the ISC or the UNDP and do not commit these organizations. Suggested citation: International Science Council. 2020. Conversations on Rethinking Human Development, International Science Council, Paris. DOI: 10.24948/2020.09 ISBN: 978-92-9027-800-9 Work with the ISC to advance science as a global public good. Connect with us at: www.council.science [email protected] International Science Council 5 rue Auguste Vacquerie 75116 Paris France www.twitter.com/ISC www.facebook.com/InternationalScience www.instagram.com/council.science www.linkedin.com/company/international-science-council Graphic design: Mr. Clinton Conversations on Rethinking Human Development A global dialogue on human development in today’s world FOREWORD ISC The human development approach that Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of changed the way decision-makers around Human Rights includes the right of everyone the world think about human progress was to share in scientific advancement and its developed through the work of prominent benefits. -

3268 HON. CHIP CRAVAACK HON. MIKE Mcintyre HON. H

3268 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 158, Pt. 3 March 8, 2012 service to, a free and democratic Cuba. Her the ability to give individualized attention to HONORING DR. BARBARA DAVIS work began with the International Rescue each one of its students with a 15:1 student to Committee (IRC), the first agency in Miami to faculty ratio. HON. ANN MARIE BUERKLE provide assistance to thousands of Cuban ref- UNC Pembroke has achieved national rec- OF NEW YORK ugees fleeing Castro’s communist regime, and ognition for its diversity as well as its strong IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the State Department of Public Welfare— ties with the community. U.S. News and World Cuban Refugee Emergency Center. Sylvia Thursday, March 8, 2012 Report has deemed the University ‘‘the most continues fighting relentlessly for Cuba’s free- Ms. BUERKLE. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to diverse University in the South,’’ the Princeton dom today, as a co-founder of M.A.R. por recognize Dr. Barbara Davis for 25 years of Cuba (Mothers & Women Against Oppres- Review has named UNC Pembroke among service to the Hebrew Day School in Syra- sion), and the Assembly of the Cuban Resist- the ‘‘Best in the Southeast,’’ and the University cuse, New York. ance. This organization is committed to the was named to President Obama’s Community Dr. Davis earned her Bachelor’s Degree defense of human rights and freedoms of Service Honor Roll for three consecutive from Barnard College and received an M.A. Cuban people, the support of Cuban political years. Additionally, the Carnegie Foundation and Ph.D. -

July 8, 2020 President Donald J. Trump the White House 1600

July 8, 2020 President Donald J. Trump The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: Thank you for your leadership as our country recovers from the economic fallout resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, including by signing bipartisan legislation, like the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act, into law. You listened to the concerns of small business employers about the negative impacts posed by the failure to fully reopen the economy and the barriers to effectively rehiring employees created by enhanced government unemployment benefits. As negotiations on further federal legislative actions begin, we write to urge you to firmly oppose any extension of the $600 supplemental unemployment insurance (UI) enacted in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Future legislation should only include policies that encourage businesses to reopen and hire employees. In fact, extending the $600 supplemental UI payments will only slow our economic recovery. According to the Congressional Budget Office, extending the supplemental UI program through the end of the year would result in approximately five of every six recipients receiving benefits that exceed their expected earnings when they return to work. It should be a fundamental principle that government benefits should not pay Americans more than if they went to work. The result is no surprise: CBO determined extending this program would result in higher unemployment in both 2020 and 2021. Small businesses are facing unprecedented challenges caused by COVID-19 and the resulting lockdowns enacted by state and local governments. There could not be a worse time for the federal government to create disincentives for returning to work. -

115Th Congress 281

VIRGINIA 115th Congress 281 NJ, 1990; Ph.D., in economics, American University, Washington, DC, 1995; family: wife, Laura; children: Jonathan and Sophia; committees: Budget; Education and the Workforce; Small Business; elected to the 114th Congress on November 4, 2014; reelected to the 115th Congress on November 8, 2016. Office Listings http://www.brat.house.gov facebook: representativedavebrat twitter: @repdavebrat 1628 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–2815 Chief of Staff.—Mark Kelly. FAX: 225–0011 Scheduler.—Grace Walt. ¨ Legislative Director.—Zoe O’Herin. Press Secretary.—Julianna Heerschap. 4201 Dominion Boulevard, Suite 110, Glen Allen, VA 23060 ................................................ (804) 747–4073 9104 Courthouse Road, Room 249, Spotsylvania, VA 22553 .................................................. (540) 507–7216 Counties: AMELIA, CHESTERFIELD (part), CULPEPER, GOOCHLAND, HENRICO (part), LOUISA, NOTTOWAY, ORANGE, POWHATAN, AND SPOTSYLVANIA (part). Population (2010), 727,366. ZIP Codes: 20106, 20186, 22407–08, 22433, 22508, 22534, 22542, 22551, 22553, 22565, 22567, 22580, 22701, 22713– 14, 22718, 22724, 22726, 22729, 22733–37, 22740–41, 22923, 22942, 22947, 22957, 22960, 22972, 22974, 23002, 23015, 23024, 23038–39, 23058–60, 23063, 23065, 23067, 23083–84, 23093, 23102–03, 23112–14, 23117, 23120, 23129, 23139, 23146, 23153, 23160, 23222, 23224–30, 23233–38, 23294, 23297, 23824, 23832–33, 23838, 23850, 23922, 23930, 23955, 23966 *** EIGHTH DISTRICT DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in the Free Territory of Tri- este, June 20, 1950; education: B.A., Williams College, MA, 1972; professional: Ambassador to Switzerland and Liechtenstein 2009–13; 36th Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, 1990–98; co- founder of the Northern Virginia Technology Council; former chair of Jobs for Virginia Grad- uates; served on Board of the D.C. -

Congressional Pictorial Directory.Indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman

S. Prt. 112-1 One Hundred Twelfth Congress Congressional Pictorial Directory 2011 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 2011 congressional pictorial directory.indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800; Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-087912-8 online version: www.fdsys.gov congressional pictorial directory.indb II 5/16/11 10:19 AM Contents Photographs of: Page President Barack H. Obama ................... V Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. .............VII Speaker of the House John A. Boehner ......... IX President pro tempore of the Senate Daniel K. Inouye .......................... XI Photographs of: Senate and House Leadership ............XII-XIII Senate Officers and Officials ............. XIV-XVI House Officers and Officials ............XVII-XVIII Capitol Officials ........................... XIX Members (by State/District no.) ............ 1-152 Delegates and Resident Commissioner .... 153-154 State Delegations ........................ 155-177 Party Division ............................... 178 Alphabetical lists of: Senators ............................. 181-184 Representatives ....................... 185-197 Delegates and Resident Commissioner ........ 198 Closing date for compilation of the Pictorial Directory was March 4, 2011. * House terms not consecutive. † Also served previous Senate terms. †† Four-year term, elected 2008. congressional pictorial directory.indb III 5/16/11 10:19 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb IV 5/16/11 10:19 AM Barack H. Obama President of the United States congressional pictorial directory.indb V 5/16/11 10:20 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb VI 5/16/11 10:20 AM Joseph R. -

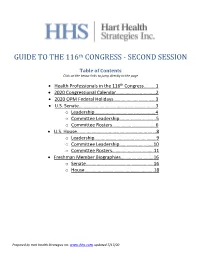

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep.