City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

Contribution of Public Service Media in Promoting Social Cohesion

COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L’EUROPE Contribution of public service media in promoting social cohesion and integrating all communities and generations Implementation of Committee of Ministers Recommendation Rec (97) 21 on media and the promotion of a culture of tolerance Group of Specialists on Public Service Media in the Information Society (MC-S-PSM) H/Inf (2009) 5 Contribution of public service media in promoting social cohesion and integrating all communities and generations Implementation of Committee of Ministers’ Recommendation Rec (97) 21 on media and the promotion of a culture of tolerance Report prepared by the Group of Specialists on Public Service Media in the Information Society (MC-S-PSM), November 2008 Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs Council of Europe Strasbourg, June 2009 Édition française : La contribution des médias de service public à la promotion de la cohésion sociale et a l’intégration de toutes les communautés et générations Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex http://www.coe.int/ © Council of Europe 2009 Printed at the Council of Europe Contents Executive summary . .5 Introduction . .5 Key developments . .6 Workforce . 6 Requirements . .11 Content and services . 13 Conclusions, recommendations and proposals for further action . 18 Conclusions . .18 Recommendations and proposals for further action . .20 Appendix A. Recommendation No. R (97) 21 . 22 Recommendation No. R (97) 21 on Appendix to Recommendation No. R the media and the promotion of a (97) 21 . .22 culture of tolerance . .22 Appendix B. Questionnaire on public service media and the promotion of a culture of tolerance . -

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Panagiota Kaltsa

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy 160 Packard Avenue, Medford, MA, 02155 Panagiota Kaltsa 102 Curtis Street, Somerville, MA 02144, USA Email: [email protected] Web: www.panagiotakaltsa.com Skype: panagiota.kaltsa 1 “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.” A. Einstein For my parents, Fotini and George, who gave me the opportunity to achieve my dreams 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Preface 6 Introduction 7 Thesis Outline Part I 12 Chapter I – Why Participation 13 Market for Loyalties 13 The market model 13 The national identity 15 The Greek case 16 The market 16 The Greek identity 18 The role of New Communication Technology in the Market for Loyalties 22 Regulation vs Participatory governance 26 Chapter II - Participation Theory 29 Definition of Participation 29 Research Method 31 Literature Review 32 Classification model 36 Transitioning from Vertical to Horizontal to Viral Participation 38 Participation Clusters 43 Vertical 43 Government 43 Corporate 47 Horizontal 51 Individual 51 Community 54 Cultural 60 Viral 61 Digital 61 Technological 71 Part II 74 Chapter III - Digital Participation Initiatives 75 Field Research findings 75 3 Code for America 76 Votizen 77 Active Voice 78 Lessons Learned 84 Chapter IV – Participation Communication Plan 86 E-governance: Benefits and Drawbacks 86 Benefits 84 Drawbacks 88 Communication Strategy 90 People 91 Objective 96 Strategy 97 Technology 101 Proposed Business Plan 107 Identifying the Problem 107 Suggested Organization Structure 108 Function 110 Conclusion 114 Moving Forward 114 Epilogue 116 Appendix 1: National and International Media Coverage analysis on 118 Greece in 2011 Appendix 2: Lincoln Toolkit 127 Appendix 3: Hellenic Statistic Service Graphs from Chapter 4 140 Bibliography 143 4 Executive Summary This work aims to set a framework for governments in crisis to strengthen their identity power and regain the trust of citizens, via participation and new communication technologies. -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Increased Transparency and Efficiency in Public Service Broadcasting

Competition Policy Newsletter Increased transparency and efficiency in public service AID STATE broadcasting. Recent cases in Spain and Germany (1) Pedro Dias and Alexandra Antoniadis Introduction The annual contribution granted to RTVE was made dependent upon the adoption of measures Since the adoption of the Broadcasting Communi- to increase efficiency. The Spanish authorities cation in 200, the Commission followed a struc- commissioned a study on the financial situation tured and consistent approach in dealing with of RTVE which revealed that the — at the time numerous complaints lodged against the financ- — existing workforce exceeded what was neces- ing of public service broadcasters in Europe. It sary for the fulfilment of the public service tasks. reviewed in particular the existing financing Agreement could be reached between the Span- regimes and discussed with Member States meas- ish authorities, RTVE and trade unions on a sig- ures to ensure full compliance with the EU State nificant reduction of the workforce through early aid rules. The experience has been positive: Sev- retirement measures. The Spanish State decided to eral Member States have either already changed or finance these measures, thus alleviating RTVE of committed themselves to changing the financing costs it would normally have to bear. The savings rules for public service broadcasters to implement in terms of labour costs and consequently pub- fundamental principles of transparency and pro- lic service costs of RTVE exceeded the financial portionality (2). burden of the Spanish State due to the financing of the workforce reduction measures. The Com- The present article reviews the two most recent mission approved the aid under Article 86 (2) EC decisions in this field which are examples of Treaty, also considering the overall reduction of increased efficiency and transparency in public State aid to the public service broadcaster (). -

Small Business Fibe TV Channel List for Current Pricing, Please Visit: Bell.Ca/Businessfibetv

Ontario | May 2016 Small Business Fibe TV Channel List For current pricing, please visit: bell.ca/businessfibetv Starter MTV . 573 HLN Headline News . 508 Investigation Discovery (ID) . 528 Includes over 25 channels MTV HD . 1,573 HLN Headline News HD . 1508 Investigation Discovery (ID) HD . 1528 MuchMusic . 570 KTLA . 298 Lifetime . 335 AMI audio . 49 MyTV Buffalo . 293 KTLA HD . 1298 Lifetime HD . 1335 AMI télé . 50 MyTV Buffalo HD . 1,293 M3 . 571 Love Nature . 1661 AMI TV . 48 Météo Média . 105 M3 HD . 1571 MovieTime . 340 APTN . 214 Météo Média HD . 1105 Mediaset Italia . 698 MovieTime HD . 1340 APTN HD . 1214 NTV - St . John’s . 212 MTV2 . 574 MSNBC HD . 1506 CBC - Local . 205 Radio Centre-Ville . 960 National Geographic . 524 NBA TV Canada . 415 CBC - Local HD . 1205 Radio France Internationale . 971 National Geographic HD . 1524 NBA TV Canada HD . 1415 CHCH . 211 Space . 627 NFL Network . 448 Nat Geo Wild . 530 CHCH HD . 1211 Space HD . 1627 NFL Network HD . 1448 Nat Geo Wild HD . 1530 Citytv - Local . 204 Sportsnet - East . 406 Nuevo Mundo . 865 NBC - West . 285 Citytv - Local HD . 1204 Sportsnet - East HD . 1406 OLN . 411 NBC - West HD . 1285 CPAC - English . 512 Sportsnet - Ontario . 405 OLN HD . 1411 Nickelodeon . 559 CPAC - French . 144 Sportsnet - Ontario HD . 1405 PeachTree TV . 294 Oprah Winfrey Network . 526 CTV - Local . 201 Sportsnet - Pacific . 407 PeachTree TV HD . 1294 Oprah Winfrey Network HD . 1526 CTV - Local HD . 1201 Sportsnet - Pacific HD . 1407 Russia Today . 517 OutTV . 609 CTV Two - Local . 501 Sportsnet - West . 408 Showcase . 616 OutTV HD . -

Greece: Audio Visual Market Guide Page 1 of 4 Greece: Audio Visual Market Guide

Greece: Audio Visual Market Guide Page 1 of 4 Greece: Audio Visual Market Guide Betty Alexandropoulou December 14 Overview The audio-visual (AV) market in Greece is showing signs of recovery after 4 years of double-digit decline for home audio and cinema spending. Retail sales have demonstrated signs of recovering, along with expected GDP growth in 2015. Demand for audiovisual equipment is covered by imports, mainly from European Union countries China, Korea, and Japan. The United States is a supplier of computers and peripherals.. Out of a population of 10.8 million people and 3.7 million households, there is an average of two television sets per household. Ninety-nine percent of these households have access to free broadcast TV, 19.5 percent have access to satellite and IP Pay TV, and 3 percent have satellite internet and pay TV bundled service. Market Trends The end of 2014 is expected to mark the completion of analogue broadcasting and a transfer to digital service. The switchover requires technological upgrades for media outlets, households, and businesses. Within this context, Digea was formed as a network operator providing a digital terrestrial television transmission in Greece for seven nationwide private TV channels (Alpha TV, Alter Channel, ANT1,Macedonia TV, Mega Channel, Skai TV, and Star Channel). In addition to these free nationwide broadcast stations, the network is open to other station broadcasts. With respect to pay-TV, fierce competition between the two main providers (Nova/Forthnet & OTE) resulted in record-high satellite and IP-TV subscriptions as well as the introduction of new channels and relevant content by the two rival platforms. -

Press Release Potsdam Declaration

Press Release Potsdam 19.10.2018 Potsdam Declaration signed by 21 public broadcasters from Europe “In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe.” A joint statement, emphasizing the inclusive rather than divisive mission of public broadcasting, will be signed on Friday 19th October 2018 in Potsdam. Cilla Benkö, Director General of Sveriges Radio and President of PRIX EUROPA, and representatives from 20 other European broadcasters are making their appeal: “The time to stand up for media freedom and strong public service media is now. Our countries need good quality journalism and the audiences need strong collective platforms”. The act of signing is taking place just before the Awards Ceremony of this year’s PRIX EUROPA, hosted by rbb in Berlin and Potsdam from 13-19 October under the slogan “Reflecting all voices”. The joint declaration was initiated by the Steering Committee of PRIX EUROPA, which unites the 21 broadcasters. Potsdam Declaration, 19 October 2018 (full wording) by the 21 broadcasters from the PRIX EUROPA Steering Committee: In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe. It has never been more important to carry on offering audiences a wide variety of voices and opinions and to look at complex processes from different angles. Impartial news and information that everyone can trust, content that reaches all audiences, that offers all views and brings communities together. Equally important: Public broadcasters make the joys of culture and learning available to everyone, regardless of income or background. -

European Citizen Information Project FINAL REPORT

Final report of the study on “the information of the citizen in the EU: obligations for the media and the Institutions concerning the citizen’s right to be fully and objectively informed” Prepared on behalf of the European Parliament by the European Institute for the Media Düsseldorf, 31 August 2004 Deirdre Kevin, Thorsten Ader, Oliver Carsten Fueg, Eleftheria Pertzinidou, Max Schoenthal Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Executive Summary 5 Part I Introduction 8 Part II: Country Reports Austria 15 Belgium 25 Cyprus 35 Czech Republic 42 Denmark 50 Estonia 58 Finland 65 France 72 Germany 81 Greece 90 Hungary 99 Ireland 106 Italy 113 Latvia 121 Lithuania 128 Luxembourg 134 Malta 141 Netherlands 146 Poland 154 Portugal 163 Slovak Republic 171 Slovenia 177 Spain 185 Sweden 194 United Kingdom 203 Part III Conclusions and Recommendations 211 Annexe 1: References and Sources of Information 253 Annexe 2: Questionnaire 263 2 Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to the following people for their assistance in preparing this report, and its translation, and also those national media experts who commented on the country reports or helped to provide data, and to the people who responded to our questionnaire on media pluralism and national systems: Jean-Louis Antoine-Grégoire (EP) Gérard Laprat (EP) Kevin Aquilina (MT) Evelyne Lentzen (BE) Péter Bajomi-Lázár (HU) Emmanuelle Machet (FR) Maria Teresa Balostro (EP) Bernd Malzanini (DE) Andrea Beckers (DE) Roberto Mastroianni (IT) Marcel Betzel (NL) Marie McGonagle (IE) Yvonne Blanz (DE) Andris Mellakauls (LV) Johanna Boogerd-Quaak (NL) René Michalski (DE) Martin Brinnen (SE) Dunja Mijatovic (BA) Maja Cappello (IT) António Moreira Teixeira (PT) Izabella Chruslinska (PL) Erik Nordahl Svendsen (DK) Nuno Conde (PT) Vibeke G. -

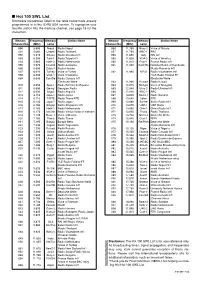

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Drama Directory

2015 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia ......................................................................... 124 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 127 Luxembourg ............................................................ 133 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 135 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 137 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 147 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 153 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal ................................................................... 159 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 165 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia .................................................................... 174